BALLROOM BLITZ

"The safest and gayest restaurant in town—even in air raids. Twenty feet below ground".

So touted the newspaper advertisements for London’s West End night club, the posh Café de Paris. The club’s celebrity manager, Danish-born Martinus Poulsen, promised that Londoners and servicemen and women could dance the night away in the safety of a dance floor two stories below ground. On the night of March 8, 1941 during the height of the London Blitz, the Luftwaffe would demonstrate the folly of that claim in one horrific, blinding flash.

When Reichsmarschall Herman Goering failed to strike a decisive blow to the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain, thus sweeping British opposition from the skies in advance of a planned invasion of England, he changed tactics and took the bombing campaign to the English population.

The campaign which would come to be known as the London Blitz started before the end of the Battle of Britain, overlapping the two aerial battles by almost two months. The Battle of Britain officially ended on October 31st, 1940, less than four months after it started, though the start and end dates are open to interpretation. Historically speaking, the Blitz began on Saturday, September 7th, 1940 when nearly 350 German Heinkel and Dornier medium bombers launched an attack on London’s East End. The day came to be known as Black Saturday because of the number of innocent and unprepared citizens who were killed. In just the one afternoon and night, the East End suffered approximately 450 fatalities and around 1,500 injured, some terribly. From Black Saturday onwards, London’s neighbourhoods would be attacked by massive night bombing raids 71 times.

Luftwaffe Dornier Do 217 bombers flying over the Thames near Plumstead, east of London on September 7th, 1940, the day that is today considered to be the first day of the London Blitz. On this day and for the next eight months, England and London in particular, would endure a nightmare bombing campaign that would claim 43,000 lives. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Previous to Black Saturday, London had been largely immune to attack, but now the Luftwaffe had started targeting East London’s docks with collateral damage to homes and families. Ostensibly, it was the Luftwaffe’s intention to break the industrial infrastructure of London by attacking its dock yards, factories, warehouses, armouries and rail yards. The continued targeting of East London forced the evacuation of children to safer rural regions. Within weeks of Black Saturday, the attacks were being executed in the relative safety (for the Luftwaffe) of nighttime. The blindness of the blackout, the wailing sirens, the sweeping searchlights and the sharp barking of anti-aircraft guns served to create a dark world of fear, unpredictability and random mayhem that was deliberately carried out to harass and intimidate the population in a psychological campaign of terror.

Though London was attacked 71 times in the eight months of the Blitz, the air raid sirens sounded nearly every night as the Luftwaffe crossed the coast for other urban targets like Liverpool, Bristol, Hull, Coventry, Sheffield, Manchester and many other industrial cities from Belfast to Cardiff. Each night as the sirens began their demonic howling, Londoners dutifully headed for air raid shelters. These ranged from small “Anderson” garden shelters for a single family, to designated community shelters in the basements of apartment and office buildings and even the London subway system where thousands of weary London families gathered in the pale light to ride out the iron storm above. The subway authorities would suspend operation in certain stations so that families could sleep in relative safety and in the early morning, those who had spent the night in “The Tube” climbed up into the dust and smoke to attend to the wounded, clean up and prepare to carry on.

After a night of bombing in London, firefighters watch helplessly as a five-story building collapses into the street. Photo: Imperial War Museum

To escape the bombing, Londoners took to sleeping in the underground safety of the London subway system. Citizens had a false sense of safety spending the night in “The Tube” and that feeling of subterranean invincibility gave rise to the Café de Paris’ unwarranted claim to being the safest nightclub in town. In fact, many people were killed while sheltering in the subway. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The truth was, however, that London’s underground subway stations and tunnels were not totally immune to the horrific effects of a direct hit from above. Three consecutive nights in October of 1940 demonstrated exactly that. On the night of the 12th of October, several bombs hit in the area of Trafalgar Square. the National Gallery was hit and what may have been a bomb from the same stick hit the roadway above Trafalgar Square Underground Station. The Bomb pierced the roadway and exploded in the booking hall killing seven people and injuring thirty-three.

The following night another bomb fell on houses adjacent to Bounds Green Station in southwest London, causing the collapse of the tunnel roof and killing 19 people sheltering in the station below, many victims being Belgian refugees.

One night later, a bomb struck Balham station resulting in a horrific catastrophe. A single 1,400 kg German bomb struck the road above the station, which was being used as an air-raid shelter by approximately 600 civilians. The semi-armour-piercing bomb penetrated the road surface and exploded about 32 feet (9.8 meters) underground, just above a cross-passageway between the two platforms. This caused the northern end of the northbound tunnel to collapse. The explosion ruptured major water and sewage mains. Millions of gallons of water, mud, and soil flooded the tunnels in pitch darkness, trapping many people. The water-tight doors, designed to keep floodwaters out, tragically trapped the water and debris inside the station, leading to many deaths by drowning. Seconds after the explosion, the No. 88 bus ravelling in the blackout, drove straight into the crater. The exact death toll varies slightly by source, but the official Commonwealth War Graves Commission figure is 68 civilian and London Transport staff deaths. Around 70 others were injured. The last bodies were not recovered until December 1940. The full story of the event was never fully revealed to the London public for fear that it would discourage people from using the Underground as a shelter.

One of the most iconic images from the London Blitz is the scene at the Balham Green station showing a No. 88 London bus which had driven into the crater created by the explosion seconds after the hole opened up. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In early January, 1941 another German bomb made a direct hit on Bank Station, across the street from Mansion House, the historic home of the Lord Mayor of London. The high-explosive bomb (possibly a 4,000-pound "Satan" or a large general-purpose bomb) penetrated the road surface at Bank Junction and exploded in the station's booking hall, which was just beneath the road. The blast travelled down the stairs and escalators, killing many people who were sheltering in the tunnels and on the platforms. Initial reports varied, but the confirmed death toll is generally accepted as 56 people, with around 69 to 70 seriously injured. Some sources, incorporating those who later died of injuries, put the total death toll at 111. The explosion left an enormous crater, estimated at 1,800 square feet (167 sq m) in area, at the busy intersection where nine streets met. The station was closed for two months while the site was cleared and a temporary steel Bailey bridge was constructed over the crater to allow traffic to pass.

The Bank of England and Royal Exchange after the raid during the night of 11 January 1941. The bomb exploded in the booking-hall of the Bank Underground Station. The crater was the largest in London. The Royal Exchange in the right background displays a massive and ironic banner, encouraging Londoners to DIG FOR VICTORY. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Sometimes it was not an actual bomb that resulted in the death of civilians, but rather the panic that an air raid created. On March 3rd, 1941 an air-raid siren sounded, and a large crowd of people ran for shelter to Bethnal Green Station in northeast London. Witnesses said that a woman with a baby tripped on the wet, dark stairs, leading to a chain reaction and a massive crush of people. The siren was followed by the loud noise of a new anti-aircraft rocket being tested nearby, which people mistook for an enemy attack. Within seconds, around 300 people were trapped on the stairs, and 173 were killed by asphyxiation from crushing and trampling. The government kept the details of the disaster secret for many years to prevent damage to public morale and avoid giving propaganda advantages to the enemy. The disaster was the worst single-event loss of life in the London Underground. Many survivors suffered long-term trauma, and a substantial memorial now stands at the station to commemorate the victims.

The government’s censorship of the horrific details may have kept the truth from the citizenry, particularly the case of the Bounds Green, Bank and Balham Station disasters, but it was a deadly lottery Londoners were forced to play regardless. Overall, Londoners believed they were relatively safe anywhere below ground. Even in a nightclub.

The stage and dance floor of the Cafe de Paris in happier times before the war. Well-heeled men in tuxedos and glamorous women in full length gowns lent the club its an air of sophistication and built its reputation as a club for the rich and famous. The Prince of Wales was a regular on the dance floor.

There may have been a war going on and almost nightly air raid warnings, but Londoners, political and military refugees and servicemen and women were not going to be deprived of their pleasures. Dancing, listening to popular music and a night out in a restaurant or nightclub was in fact the only available tonic for the stresses of the Blitz and the war at large. There were a smaller number of London nightclubs operating throughout the Blitz. Most clubs were denied a license to operate by Westminster Council because of the strict blackout regulations. However, London authorities made an exception for the Café de Paris, believing it to be safe and light emission free. A bomb shelter and dance club in one. Of the few that could still open their doors, the Café de Paris was the most popular — the Peppermint Lounge or Studio 54 of its day. Before the war, its patrons included the Prince of Wales (the future Nazi-friendly King Edward VII), Marlene Dietrich, Anna May Wong, Noel Coward, American actresses Dorothy Dandridge and Louise Brooks and more.

By the time the Blitz had begun, the clientele was much broader than the high society patrons of the 1920s and 30s with plenty of “colonials” and foreign nationals as well as service men and women of all stripes, West End Theater District actors, producers, dancers and actresses. Beverly Baxter (a male), a MacLean’s Magazine correspondent described the Café de Paris as:

“a certain West-End restaurant where the band was excellent, the dance floor adequate and the service… par excellence. … A place where the young and foolish were overcharged.”

Another writer quipped:

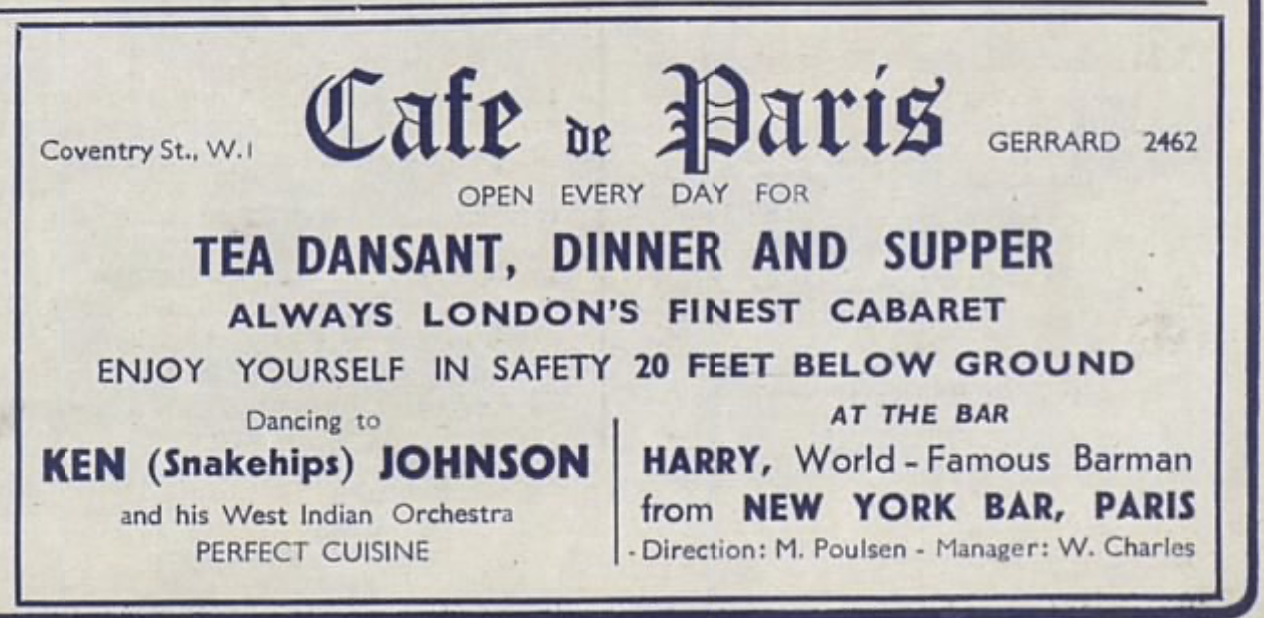

The Café de Paris on Coventry Street was one of the most popular nightclubs in all of London. As the Blitz descended on London, the proprietors of the West end club took advantage of their subterranean situation to entice patrons as this advertisement in the society magazine Tatler and Bystander on March 5, three days before the club was destroyed by a German bomb. Image via Newspapers.com

“revellers groped their way through the black-out to the Savoy and the Café de Paris…and enjoyed the added thrill of dancing the night away while anti-aircraft guns thudded away outside”.

The Café de Paris was a basement venue beneath the Rialto Theatre on Coventry Street a short distance east of Piccadilly Circus. Patrons entered the club at street level next to the main entrance for the Rialto Theatre, the building’s main tenant. Descending a set of stairs, they arrived at a curved balcony overlooking the stage, restaurant and dance floor. From there, two sets of stairs wrapped around either side of the stage down to the main floor. The arrival of each guest coming down the stairs was theatre in itself and patrons scanned the arrivals for a well known face, a spectacular gown or a handsome officer. The oval shaped restaurant was arranged on three sides of the dance floor under an overhanging gallery and seated up to 400.

“I’ll get London swinging, or die trying.”

The Café de Paris had been home over the years to many in-house bands including Teddy Brown and His Café de Paris Dance Band. A former percussionist with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Brown was born Abraham Himmelbrand in New York and weighed in at nearly 350 pounds. By 1941 the in-house band was Ken “Snakehips” Johnson and his all-black West Indian Dance Orchestra — one of the most popular bands in all of London and historically one of the seminal orchestras in the early English jazz scene.

Kendrick Reginald Hijmans Johnson was born in British Guyana in 1914 and was sent to Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School in England at the age of 14 with the expectation that he would eventually study medicine like his father. Trouble was that Kendrick loved to dance and to be in the spotlight. After a stint on a Harlem, New York nightclub, Kendrick earned the nickname “Snakehips” because of his unique hypnotic dance moves.

Kendrick Johnson (left) conducting the Kendrick Johnson Band (as it was known before it became the house band at Café de Paris) during a 1939 BBC television broadcast from the BBC’s studios at Alexander Palace. It’s thought that the band was the first black orchestra to appear on television. Guitarist Joe Deniz sits in the front row with his guitar while Dave “Baba” Williams is at right with his face turned towards the horn section at the top.

Patrons of the Café de Paris entered down a flight of stairs from the street to the balcony seen at top of photo. From there they descended via one of two reflected curving staircases to the dance floor. The basic stair configuration remained for 100 years from the club’s opening in 1924 until as late as 2020 when the Café de Paris closed during another war — the one against COVID 19. The orchestra depicted here is Teddy Brown and His Cafe De Paris Dance Band, with the 350 lb. xylophonist Teddy Brown at right. Not surprisingly, Teddy died of a heart attack at 45.

The popularity of American jazz music was on the rise, and Snakehips was the toast of London’s music scene. His band, the West Indian Dance Orchestra (formerly the Aristocrats of Jazz) was one of the best and Johnson was their front man, albeit one who was not qualified for the job musically. According to Joe Deniz, his longtime Cardiff-born guitarist, Johnson had no training in musical arrangement nor could he read music, but he was the ultimate showman. His hip wriggling and tap dancing combined with his electric smile, his 6’-4” frame, an extra-long baton and flair for tuxes and long white tails fashioned after Cab Calloway, drew all eyes in the room to him.

Despite being the talk of the town and someone people flocked to in order to assuage their stress, he lived in a world that tolerated him only because of his entertaining dance moves and energetic jazz music. Canadian-born writer, British politician, Lord Beaverbrook favourite and utter racist Beverly Baxter had this to say about Johnson in his dispatches to MacLean’s magazine called London Letters:

“The band was composed of negroes led by a darkie whom the London Smart Set had named “Snakehips”. He was long, thin, graceful and had a smile that only belongs to a race not long since freed from slavery.”

One shudders at how the bigot Baxter would have described Kendrick if he knew he was also gay. In those days and in that city, being a gay man was not something you would advertise. Just ask Alan Turing, the English mathematician who led the team that broke the Enigma code.

At 6’-4” with a winning smile and dazzling dance moves, Kendrick “Snakehips” Johnson was the perfect man to lead an all-black band in London. According to his guitarist Joe Deniz in an 80s TV interview, Johnson knew nothing about musical arrangement and conducting. He made it up on the fly and eventually figured out how to conduct. It was saxophonist/clarinetist Joe Barriteau who was the musical director of the band.

Even Johnson himself leaned heavily into the fact that band was made up entirely of black men. Though it was named The West Indian Dance Orchestra (Formerly the Aristocrats of Jazz) several of the bands members were British — English and Welsh. Because there was no black trombone player of suitable talent available in London, a couple of white trombonists were recruited over time, each one having to "black up" with burnt cork to maintain the orchestra's advertised racial homogeneity. While this might be seen in a poor light today, London society mores dictated that while mixed race bands were unacceptable, an all-black band was a tolerable novelty.

On the night of March 8, 1941, just five days after the Bethnal Green Station disaster, the club director Martinus Poulsen was hosting a “Service Night” with an open invitation to all members of the military services who could afford the entry charge and dinner. Nineteen-year old Royal Canadian Army Service Corp Sergeant Richard Albert Bradshaw, of Ottawa, Ontario had been in London since June 1940 with the Canadian Active Service Force, the Canadian Army's primary expeditionary field force raised during the Second World War. It was distinct from the existing militia forces and was specifically organized for overseas service. Bradshaw was a logistics and quartermaster sergeant with the Canadian Army, helping to lay the groundwork for the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Canucks over the next four years.

While in London, Bradshaw made friends with another soldier by the name of Gordon Wapren Quinn, from Pembroke, Ontario, a corporal with the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps. Quinn, at 40 years old, had also grown up in Ottawa. Having spent much of the past year under the stresses of preparing the ground for the Canadian Army units which would soon be arriving by the shipload as well as enduring half a year of air raids and destruction, the men were looking forward to joining other Canadian friends, tucking into a rare good meal at the Café de Paris and hitting the dance floor with their dates. It all promised to be a wonderful diversion, worth the difficulties in getting to the West End under blackout restrictions and the risk of bombs falling from above.

Sergeant Richard Bradshaw was from Ottawa. He and Ottawa Valley friend Gord Quinn were both killed. Photo via Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Despite the blackout, London’s bus system, underground and famous black cabs still operated, feeling their way in the gloom with dimmed and hooded headlights. Likely the two Canadians and their girls took a bus to Piccadilly Circus and walked the short distance in the dark to the club on Coventry street. A doorman greeted them at the entrance and opened the door onto a dimly lit stairway that led down to the mezzanine. Finally out of the cold night air, they could feel the warmth of the club rising up the stairs and see the bright lights below where the sounds of a crowded restaurant rose — women’s laughter, clattering dishes, indistinct conversations. Descending to the mezzanine, they doffed their great coats, gloves and caps, handing them to George, “London’s most famous cloak room attendant,” and took a receipt. As they approached the balcony overlooking the dance floor they were met by club manager and maitre-d’ Matinus Poulsen who loved to welcome everyone to his club. The balcony was immediately above the backstage dressing rooms and partially covering the stage area where members of the West Indian Orchestra were setting up their music stands and arranging chairs while the club’s female dancers were waiting off stage for their part in the show..

The men descended the stairs into the blue haze of cigarette and cigar smoke and the relaxed buzz of the safest and gayest club in London while Poulsen led them to their table where they would join other Canadians—nurses and headquarters types. It was about 8:30 pm and the band was due on stage shortly. From Canadian Army headquarters Bradshaw would have recognized a number of Canadian Army officers sitting at a white clothed circular table accompanied by a couple of attractive Canadian nurses. They were Captain Phillip Seagram, the aide de camp of the boss (Major-General Andrew McNaughton, the commander of the Canadian expeditionary force), Captain Robert George Robarts and R. R. Young of Toronto. At a nearby table sat another group of Canadians — Captain John Cameron Clunie and Lieutenant David Wright, both from Sarnia, Ontario with their dates— Nursing Sisters Thelma Blanche Stewart of Toronto and Helen Marie Stevens of Dunnville on Lake Ontario.

Seagram stood out from the rest. He was tall, handsome and wore a custom tailored uniform. He exuded the kind of erudite confidence that came from his breeding and upbringing—a scion of the world-famous distilling Seagram family of Waterloo, Ontario. He was the eldest son of Edward Frowde Seagram, the one-time head of the Seagram Distillery empire. Seagram’s’ now-world-famous Crown Royal blended Canadian whiskey was first created just two years earlier in 1939 for the Royal Tour of Canada by King George and Queen Elizabeth. Seagram was educated at two of Ontario’s most exclusive prep schools — Ridley College and Upper Canada College. He was a serving member of Toronto’s fabled 48th Highlander Regiment, the first Canadian regiment to embark for Great Britain following the declaration of war. He was in London on leave from Junior Staff Course at War College. His brother LCol J.E. Frowde Seagram, would command the regiment’s 2nd Battalion later in the war. With his well-heeled charm and wealth, the young Captain Seagram held court at a table near the stage.

Captain Phillip Seagram (Left), scion of a wealthy Canadian distilling family, was Major-General Andrew McNaughton’s (far right) Aide-de-camp (Note ADC armband). Being high born and highly educated meant he would get plum assignments like ADC and a chance to shake hands with King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Photo via Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Outside the club and far over their heads in the blackness of an unsettled London sky under a waxing gibbous moon, all was quiet. In parks and on rooftops around London, searchlight and anti-aircraft crews were eating bully beef sandwiches and smoking cigarettes, awaiting the inevitable. Down on the streets, Air Raid Wardens were sharply tweeting their whistles at anyone who had not yet drawn their curtains. Men at the fire stations brewed a last hot tea for the night. Eyes were alternately used to pick a path on the cobbled streets and to scan the slice of night sky visible from the streets. The Luftwaffe bomber crews were already in the air, only half an hour away.

At 7:20 PM, twenty kilometres southeast of the Café de Paris, at RAF Biggin Hill, the first of 12 black-painted Boulton Paul Defiant turret-gun night fighters of 264 Squadron, Royal Air Force began to rise sluggishly into the night sky. They climbed for altitude and their assigned sector in what they all knew would be a hopeless search for German bombers in the scudding cloud and drifting rain showers. They would continue to launch intervals for the next two and a half hours. As 8:30 approached, the air raid sirens began to wail and across the city, those who had not already done so, headed for shelters or descended into the murk of the subway system.

A 264 Squadron Defiant warms up on the ramp at RAF Biggin Hill for a night sortie against Luftwaffe raiders over London. Photo: Imperial War Museum

At 9:43, the last to take off were the squadron’s commander, 30-year old Squadron Leader Phillip James Sanders and his turret gunner, Pilot Officer William Roy Moore, also 30 years old. By the time they took off to join the others, some of whom had taken off hours before and had already landed back, the invisible Germans were already dropping their bombs in an all-out and indiscriminate attack on London that wouldn’t end until 4 AM the following morning. The Defiants took off at intervals to allow them to get to their assigned area without the threat of an air-to-air collision with another night fighter. Each patrolled the sky under the direction of ground control for an average of an hour and a half and all reported nothing, shot at nothing and found nothing even though hundreds of German bombers were to attack London that night. Though the courage of Sanders and his pilots was beyond question, they would make absolutely zero contact with the enemy that night as was normal on almost every night, such was the effectiveness of London’s night fighter system in early 1941. In fact, two of the Defiants never made it off the runway—one Defiant taxied in total blackout due to enemy aircraft in the area, and crossed the runway just as the other was taking off, resulting in the destruction of both aircraft and the hospitalization of all four men.

They weren’t the only night fighters launching that evening. At RAF Debden, northeast of London, 85 Squadron launched seven of their Hawker Hurricanes, led by dashing Squadron Leader Peter Townsend, who would later come to be involved with Princess Margaret. At RAF Gravesend, 30 kilometres to the east of London, 141 Squadron launched another seven Defiant turret fighters. Between the three squadrons, there were 26 night fighter sorties, but there would be no contact with German raiders over London that night

In the dark and dangerous sky of London on that terrible night, the Luftwaffe came in waves. Droning Heinkels and Dorniers carrying their tense and grim crews, released their loads of high explosives and incendiaries unmolested by night fighters but harried by searchlights and flak. The bombs began to fall and the rhythmic Richter concussions could be felt on the dance floor of the Café de Paris. Instead of instilling fear, the tectonic vibrations seemed to make people even more lively as they felt empowered by dining and dancing while Hitler and Goering were throwing their worst at London. After all, they were young, gay and invincible.

Sometime after 9 PM, Snakehips Johnson finally took the stage, having being delayed by air raid sirens, road closures and the blackout. The crowd was by now well-oiled and eager to get dancing to the beat of the West Indian Dance Orchestra. The band members pinched out their cigarettes and took their seats. Minutes later, the elegant and Cab Calloway-esque Kendrick “Snakehips” Johnson, immaculately dressed in long tails and black tie, took the stage. tapped his ridiculously long baton, smiled a dazzling smile across the dance floor, turned a page in the music sheet he could not read and called for the band to warn up with a “Dream of a Waltz” medley followed by the Count Basie classic “Don’t You Miss Your Baby”. Eager young men and women rushed to the dance floor. The club’s resident dance troupe waited in the wings behind the stage as the band began to play an instrumental version of the Ink Spots’ “Maybe” and the dancers slowed down and moved closer together, enjoying the swirling moment of closeness and human contact amid the faint seismic quakes of bomb strikes that rose from the floor. Ken Johnson surveyed the floor, smiling, swaying, relishing his power to bring a few moments of joy amid the social stresses of the Blitz.

Nursing Sister Helen Stevens of Toronto, a physiotherapist at the Canadian Army hospital in London

Just as Squadron Leader Sanders lifted his Defiant off the grass at Biggin Hill, the West Indian Dance Orchestra upped the energy level with a peppy version of “Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh. ” — a cover of a song written in 1917 and in 1940, an Andrews Sisters hit single. Like a wartime Mick Jagger, Johnson, a mesmeric front man and sexualized dancer, began to move while waving his ineffectual baton from the front of the stage. One didn't have to take to the dance floor to enjoy Ken Johnson and the West Indian Dance Orchestra. They were simply the best musicians in London and Snakehips, with his flexible, fluid, and eccentric form of jazz and tap dancing, attracted every eye in the house —male and female.

Martinus Poulsen, the Danish restaurateur and nightclub promoter who was killed along with his patrons in the bombing.

Just as revellers were swarming the dance floor, thousands of feet above in the dangerous dark, a stick of 50 kg high explosive iron bombs dropped tail first from their vertical racks in the belly of a Luftwaffe Heinkel 111. As they slid into the slipstream, their tails caught the rush of cold London air, and flipped them nose down at which point they wobbled and screamed into the darkness towards their destiny. Immediately, small vanes in their blunt noses began to spin in the air flow, driving an arming screw deep into their iron dumbness and unchaining hell. A thousand feet later they stabilized at terminal velocity, separated and arced across West London in the blackness. Two of them remained close together and fell almost as one. Unseen in a sky filled with the lashings of searchlights and the barking of antiaircraft guns, they shrieked and wailed like twin “Klagefrauen” in the Black Forest, heralding death to come. Anyone still on the streets below ducked into doorways or flattened themselves on the wet cobblestones. Seconds later the two bombs found the throat of a ventilation shaft on the roof of the Rialto Theatre, and, one after the other, plunged deep into the building, penetrating the glass-domed ceiling of the Café de Paris.

If we could pause time in that last millisecond before life ended for so many, the dance floor was swirling under sparkling light; Snakehips, the epitome of style, was smiling and high on the amphetamine of the performance; Dave “Baba” Williams was on his sax with his eyes on Johnson: David Wright was on the dance floor with Canadian nursing sister Thelma Stewart, a physiotherapist from Toronto; Martinus Poulsen was surveying the joy-filled room with satisfaction; Richard Bradshaw and Gord Quinn were heading to the floor with their dates.

But we can’t pause time. In the next millisecond all that was gone. The bombs peregrined the last 30 feet of their fall, striking the dance floor in front of the band. There was a blue flash like lightning, a massive concussive explosion delivering a shredding chrysanthemum of searing steel shrapnel followed by dust, blood and smoke-filled darkness. For a few seconds there was nothing but the ringing sound of violence and falling debris. Then screams in the blackness, chaos on the floor and agonized moans from the dying and injured. In a single second, Café de Paris, “the safest and gayest restaurant in town”, transformed from glittering dancehall to abattoir.

The woodwind section of the West Indian Dance Orchestra: L to R: George Roberts, Trinidadians Dave “Baba” Williams and Carl Barriteau.

Everyone was stunned senseless, blown with tables and chairs to the perimeter of the room. Many were dead or dying and many more were horrifically injured by shrapnel or the blast’s shockwave. In the near dark, people shrieked in pain, called out for friends and stumbled through the wreckage of chairs and bodies to escape up the stairs. David Wright who had been dancing with 23-year old Thelma Stewart reacted instinctively to the shriek and crash of the approaching bombs and turned just in time to shield her from the blast. He was killed instantly while Stevens survived with injuries including an amputated finger. Nursing Sister Helen Stevens and Captain John Clunie, who had not taken the dance floor yet, were momentarily stunned by the blast, but soon came to their senses. Immediately both began climbing over debris to find survivors and administer aid using table cloths, napkins and clothing as tourniquets and bandages. Over the next hour before organized help could arrive, Stevens did more to succour the wounded than anyone. Though she was a physiotherapist, she knew enough first aid to bandage and splint. Her story would be told with pride in the weeks and months ahead in Canadian newspapers.

Only one of the two bombs exploded, while the other buried itself in the floor; but the result was enough to create extensive carnage and destruction. Bradshaw and Quinn were killed instantly on the dance floor. Their dance partners were 18-year old Rose Woodland and an un-named girl friend. Of the four, only the friend survived. There were many young women among the dead and dying including a couple of young firewomen from the Auxiliary Fire Service. Philip Seagram, the aide-de-camp with a bright future ahead, was killed by the blast while others at the table were grievously injured. It was a horrific nightmare for the young men and women on the floor, but the orchestra suffered as well. Fully exposed to the blast, Ken Johnson was also killed instantly. Newspapers of the day, more interested in selling papers than reporting facts, vary greatly in how he died. Some reported he died without a mark on him, seemingly untouched with an angelic peaceful countenance and his red rose still in his lapel while others said he was decapitated. Dave “Baba” Williams was also killed — cut in half by the blast. All the members of the band were injured. Joe Deniz, the orchestra’s guitarist, who sat behind the grand piano was shielded from death but had serious leg injuries as did the piano player Yorke de Souza. Bassist Abe “Pops” Clare was also injured and his double base shattered.

Two of the club’s managers also died as they greeted guests and showed them to their seats. Martinus Poulsen, who arrived in England years before with a Danish Olympic team. He remained in the country finding work as a waiter before his meteoric rise to the owner of the Café de Paris. Affectionately referred to as the ‘smiling waiter’, Martinus was 51 years old when he died along with his cherished patrons. The club’s celebrity bar tender, Harry McEllone, late of world-famous Harry’s New York Bar in Paris and dressed in a tuxedo was shaking cocktails for eight guests behind that bar when he was blown over by the blast, landing bleeding in a heap on the floor amid dozens of smashed liquor bottles.

Prior to the blast, the club’s troupe of dancers had been instructed by Poulsen to delay the start of their show and remain behind stage in their dressing area. As a result all the dancers survived. They were told to remain in their dressing room, while the dead and wounded were removed from the building. One of those dancers was Eileen Farrell, then 24-years old. She would go on to a full life in dance, running a dance school into her 80s. She died in 2020 at the age of 103.

Eileen (née Taylor) Farrell (far left) poses with her dance troupe in 1938.

The Canadian Victims. Top: Captain Phillip Frowde Seagram, Corporal Gordon Wapren Quinn, Lieutenant John David Wright, Sergeant Richard Albert Bradshaw Bottom: Nursing Sister Thelma Blanche Stewart, Nursing Sister Helen Marie Stevens, Captain John Cameron Clunie, Captain Robert George Robarts

Ballard Blascheck, AKA Ballard Berkeley, a special constable of the London Metropolitan Police helped rescue survivors.

Given all the emergencies that were happening across the city and the difficulties getting through the darkened streets, it was a while before ambulances and rescue crews arrived. One of the first officials on the scene was a 37-year old special constable of the London Metropolitan Police named Ballard Blascheck, a part-time thespian whose stage name was Ballard Berkeley. Blascheck helped to extricate survivors and deal with the dead and mutilated. He was also called upon to police some suspected looting and corpse robbing which apparently happened with some of London’s less scrupulous citizens. Whether these came in off the street or were in attendance when the bomb exploded, it was to reported. While Blascheck’s name and role in the recovery would be mentioned in a few of London’s broadsheet papers, his real fame would come 35 years later when he played Major Gowan, the slightly senile, amiable, retired soldier and permanent resident in Fawlty Towers, the British cult classic TV series. For his work that night and others during the Blitz, he received the Defence Medal and by the end of the war, The Special Constabulary Long Service Medal.

The emergency response services to the Cafe de Paris bombing were slow to arrive. A confusion at the scene and poor communications with the Westminster Control Centre resulted in lengthy delays. Although two Heavy Rescue parties, a Mobile Aid post, two stretcher parties and two ambulances were soon on their way to Coventry Street, the urgent need for more ambulances and stretcher parties was underestimated. It would be over an hour before enough ambulances arrived. Some survivors were obliged to commandeer taxis to take some of the injured to hospital. It was reported that when one patron was carried out on a stretcher, he got a cheer from bystanders when he reputedly called out, 'At least I didn't have to pay for dinner.'

Though official response was delayed, civilian rescuers and neighbouring businesses were soon on the scene to extricate the wounded and cover the dead. Across the street, the Mapleton Hotel (now called the Thistle Piccadilly Hotel) was rocked by the explosion, but was unscathed. Within minutes, Mr. Albert Weaver a section commander in the Home Guard and the hotel’s manager, organized staff and hotel guests to help the victims. “We went straight across with torches to bring out the the injured” he stated., “Residents and members of the hotel staff helped carry them in [to the Mapleton], and to wash and dress their wounds before nurses and ambulances arrived. Everyone worked marvellously and all those trapped in the building had been released before midnight. Quite a large number were able to walk and were escorted across the street into the lounge where they recovered.”

Meanwhile the bombing of London continued unabated. Overhead the rush to rescue the living, the German bombers still droned, the flak guns still barked. Unseen in the night sky, Squadron Leader Sanders and other night fighter pilots groped blindly, unable to find and attack a single German raider. While he and his gunner Moore squinted into the inky darkness, below them, London was bleeding and burning. Buckingham Palace was hit around the same time resulting in the death of a police officer and the partial destruction of the North Lodge. A few hours later, the palace forecourt was hit again — without much damage luckily. The raid was one of the most intense of the Blitz, with 571 German bombers in successive waves flying across the city. Bombs were dropped across all parts of London, causing widespread fires and destruction. In all, the Luftwaffe dropped 130 tons of high explosives and 25,000 incendiaries and the night fighter squadrons found none of 571 bombers which took part, underlining the extreme difficulties in finding aircraft in the dark with the primitive equipment and systems at the time.

That night, another Canadian news reporter named Matthew Halton (a much respected Canadian war correspondent and father of CBC’s David Halton) had hired a taxi to drive him about the city during the massive raid so that he could experience what Londoners were experiencing daily and nightly. Earlier, while roaming the streets under the bombing raid he had been knocked to his knees by one blast.

I was standing with a policeman and a Canadian soldier watching the sensational pyrotechnics. Immense chains of chandelier flares floated slowly earthward and individual flares kept dividing into two like bacteria under a microscope.

The sky was full of droning planes, many lower than usual, but still so high you could see only trails of smoke and vapor against the sky. Bombs screamed earthward, and London’s guns shook the world with their sharp explosive roar.

Then the policeman yelled “Get down!” and as he spoke, he and the soldier flung themselves on the ground as a bomb screamed our way.

They say it sounds like an express train, and it does. It sounds like an express train covering 10 miles in 10 seconds. I didn't have time to get down before it hit. In those few endless seconds it seemed impossible that it was going to miss us.”

Halton went on with his report:

“Hundreds of guns all over London, near and far, spoke with their sharp angry violence. Bombs fell with their kind of violence, which is somehow slower and crunchier. It seemed to me that the unpleasantest part of any bomb explosion near you is not so much the explosion itself as the sound of twisting girders and falling stone as a destroyed building settles back into shattered stillness.”

The bomb had struck the street 100 yards away. Picking himself up, Halton continued on his tour of blacked-out London lit by the light of flares, searchlights and fires. By morning he had heard about the night club disaster and made his way towards Coventry Street at dawn. There outside the door of the Café de Paris he began interviewing survivors including one of the band members who was sitting on the ground. The stunned musician stated that:

“When the ghastly noise had died away and A.R.P. men came in with lights, I saw several of my best friends lying dead beside me. The bomb had dropped right on the dance floor and killed people as they danced”

Halton reported in the Toronto Star one day later that:

“In the restaurant and outside, women whose friends had just been killed or injured at their side were now helping first aid workers with the wounded. Girls ripped their dresses to make bandages. Volunteers tore doors down to make stretchers.

A gay little restaurant nearby was also hit. About 20 people were there. The owner was having a little party for his friends. He and most of his friends were killed.”

He ended his report with “I saw haggard, anxious people enquiring for loved ones and friends. And in the ruins I saw half a dozen dancing slippers and bits of evening dress”

Investigators, including a tuxedoed man who may possibly have been in the club at the time the explosion inspect the debris the next day.

Clean up begins— a civil defence worker carries Joe Deniz’ Gibson electric guitar and the remains of Pops Clare’s double bass, surrounded by broken chairs and sheet music.

Two days later, a Canadian Press news story carried by many city newspapers across the country reported on the heroic efforts of Nursing Sister Helen Stevens and Lieutenant John Cluny:

“Caught in the bombing of the Café de Paris while on leave, Nursing Sister H. M. Stevens of Dunnville Ontario., did more than anyone else to succor the wounded amid the chaos of the wrecked cabaret. Dressed in the light blue dress uniform of the nursing sisters, the 23-year old Miss Stevens moved about the debris binding gaping wounds with table cloths and clothing and putting broken limbs in makeshift splints.

Miss Stevens who was not injured herself, had visited the place with Canadian friends, including Nursing Sister Thelma Stewart of Toronto, Lt. J. C. Cluny of Sarnia, Ont. and Lt. J. D. Wright also of Sarnia who was killed.

When the bombs fell, Miss Stewart, who was injured, and Lieut. Wright were dancing, but the others, not liking the song “Oh Johnny” that was being played by the orchestra, were sitting out at the balcony table [a balcony ran around the perimeter of the club]…

…. Miss Stevens is not a nurse who deals with blood wounds every day. Along with Miss Stewart, she is a physiotherapist at a Canadian military hospital, but she pitched in working desperately and nervelessly with an army doctor, whose name she dd not learn.

Uniform Tattered

She had no thought of doing anything heroic—“I did what any Canadian nurse would be proud to do.”

Her uniform tattered and white starched cuffs blotted with blood, she ministered to the injured for more than an hour. Lt. Cluny moved ahead with the glimmering light, seeking injured under the debris. Cluny found Lt. Wright’s body, made sure that Nurse Stewart and other Canadians reached safety and then walked through the destruction pouring champagne over wounds of the injured as an antiseptic.

“Jack [Cluny] and those who helped were so cool as a Canadian spring breeze,” said Miss Stevens. “They worked with might and main. It seemed to give me courage too.”

The Butcher’s Bill

In the dim morning light of March 9, 1941 on Coventry Street, the butcher’s bill was tallied. There were 34 people killed including two members of the band, the club’s managers and four Canadian servicemen—Bradshaw, Quinn, Wright and Seagram. More than 80 others were injured, some grievously, including another six members of the orchestra. It wasn’t long before work crews began clearing the debris from the club and washing away the blood. The club’s stock of fine wines (valued at £40,000 in 1941 and $3.5 million dollars today) would be eventually sold off. The club closed its doors and would not reopen until 1948, when it would once again take its place as London’s premier night spot favoured by the city’s socialites and international celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Marlene Dietrich and Princess Margaret.

A week after the horror of that night, on March 14, there was a funeral procession and memorial for Kendrick Johnson. As the glass sided hearse carried his ashes through the streets, it also carried drummer Tom Bromley’s broken base drum, still displaying the now-symbolic damage from the explosion. Following his memorial, a significant event for the Black music community which drew many fellow musicians, his ashes were permanently placed in Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School chapel where they remain to this day.

Despite his importance to British swing music, Black music in Great Britain in general and indeed to helping Londoners, ex-patriot refugees and Allied servicemen and women to “carry on” through the nightly horrors of the Blitz, Beverley Baxter, the haughty racist Canadian columnist for the overseas “bantam” edition of MacLean’s magazine summed up the tragedy that befell the beautiful Kendrick Johnson with barely concealed distain, bordering on glee for what he thought to be a humorous turn of phrase: ““Snakehips” the ni--er orchestral leader, has conducted his last foxtrot.”

Air raid wardens and rescue personnel clear musical wreckage, including a drum set, piano and a marimba from the stage the day after the carnage at Café de Paris. The piano saved the lives of band members sitting behind its bulk. The next week at Snakehips Johnson’s funeral this drum was carried on the hearse as it drove to the cemetery.

The effects for the bombing continued to reverberate for months. In an early April, 1941 interview in Britain’s Sunday Dispatch, George, “Londons’ most famous cloakroom attendant” reported that:

“One morning a couple came in to find the gentleman’s things. He was a Canadian Army captain. His greatcoat and cap were on a peg. Beside them hung the greatcoat and cap of a major in the Canadian Army. Those will never be called for, I am sorry to say” the gentleman said to me.”

Back in Canada the toll was exacted family by family — the Bradshaw family in Ottawa, the Quinns of Pembroke and the Wrights of Sarnia. They all had thought their sons were not at risk despite the nightly bombing raids their boys were witnessing. It wasn’t like they were actively fighting the enemy. Yet, within 24 hours, each family received a telegram from Army Headquarters in Ottawa similar to the one sent to Jack Wright’s sister, Mrs. Howard Vince of Sarnia which read:

“REGRET DEEPLY LIEUTENANT JOHN DAVID WRIGHT OFFICIALLY REPORTED

KILLED ENEMY ACTION MARCH EIGHTH FURTHER IINFORMATION FOLLOWS WHEN RECEIVED”

Surely the wording of those four telegrams had the families wondering how their sons had met their deaths by enemy action when they knew they were living on London.

Martha (nee Telfer) Seagram, the wife of Captain Phillip Seagram took the news particularly hard. Her husband was the first member of the 48th Highlander Regiment to die in the war. Her physical and likely mental health declined rapidly. Despite being very young, she was found dead in her car two months after the Café de Paris bombing and one day after her 24th birthday. The reported cause of death was a heart attack and her funeral was a private affair. One wonders if the true cause of death was kept from the public.

In 2026, it will be the 85th anniversary of the bombing of “the gayest and safest club in London”. The night club would not reopen until 1948 but soon re-established itself as one of the leading theatre clubs in London, playing host to the likes of Princess Margaret, Judy Garland, Josephine Baker, Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, James Mason, David O. Selznick, Jennifer Jones, Tony Hancock, Grace Kelly and more. In the 1950s, Noël Coward often performed cabaret seasons there as did Marlene Dietrich.

In the mid-1980s, the Café de Paris was frequented by a new generation of celebrities like David Bowie, Andy Warhol, Tina Turner, Mickey Rourke, and George Michael. The scars of that night have long since faded away, washed out by the glitter and stage lighting of nearly eight further decades of entertainment, dancing and celebration. By the 21st century, the club was still going strong, the haunt of London’s theatrical, musical and art scene. The Café de Paris, survivor of the Blitz and a night of horrors, survivor of the Second World War, survivor of a full century of light depravity and emotional release, could not survive the war on Covid-19. Just when London’s citizens really needed its embrace to get through the pandemic, its doors were shuttered and its lights shut off. In 2020 a microscopic virus managed to do what 50 kg Nazi bombs failed to do so long ago. It extinguished the light.

The Imperial War Museum in Great Britain holds in its collection this memorial plaque created from bits of crockery from the Café de Paris explosion. It once belonged to Café de Paris dancer Eileen Farrell who picked up the shards as she left to club following the explosion. Photo: Imperial War Museum

By 1955, the Café de Paris had risen from the ashes of the Blitz and re-established itself as one of London’ premier night clubs, frequented by the likes of Princess Margaret and members of her “Margaret Set”. At left is her longtime companion and Lady-in-Waiting, Lady Anne Genconner and at right Lady Jane Vane-Tempest-Stewart,

The Café de Paris remained a trendy and outrageously wild nightclub into the 21st Century. It survived the London Blitz in 1941, but the COVID pandemic restrictions finally put it out of business in 2020. Photo: OnInLondon