The Red Baron and the Varsity Blue

It’s been a long time since the First World War. Anyone who was alive then is long dead. So are their children. Generations have swept over us — The Greatest, The Silent, the Baby Boom, the Millennials, and Generations X, Z and Alpha. Neighbourhoods have changed or even disappeared. The men and women who fought in that war are long forgotten — reduced to a moment of abstract silence on Remembrance Day or a yellowed image on Ancestry.com. In the savage years of the “Great War” family and neighbours mourned their losses, celebrated them in church services, plaques and calligraphic illuminations. Mothers were numbed and fathers broken. Then inexorably, the memories faded like a photo in the sun. The pain receded beneath the opiate of time. The mourners were mourned. The names were forgotten, except for the rare ones who water and tend the family trees. Every one of the millions who served in the war deserves to have his or her story told — The vaporized and the gassed, the drowned and the amputated, the broken and the haunted. This is the story of just one of them — For Remembrance Day 2025. A hundred years later but not too late.

The Red Baron and the Varsity Blue

At some point in the evening of Tuesday, April 30, 1917, Rittmeister Manfred Albrecht von Richthofen, sat down at his writing desk in his private room at the magnificent Château de Roucourt, a few kilometres from the Belgian border. As commander of Jagdstaffel (Jasta) 11, he was finishing up some squadron and personal paperwork prior to taking a break following weeks of aerial combat on the Arras front. The other pilots of Jasta 11 were celebrating their successes below in the drawing room, and not far away on the grounds of the estate, squadron mechanics were readying the unit’s Albatros D.IIIs for the next morning’s patrols.

The first order of business for the exhausted Richthofen was to clean up his Jasta’s combat reports and paperwork before handing over temporary command to his protegé Leutnant Karl Allmenröder. He looked forward to acclaim as a national hero in Berlin, receiving the Pour le Mérite (the famed Blue Max) on May 1st and had scheduled a private lunch for his 25th birthday with the Kaiser himself the day after that. He also looked forward to a visit with his mother at the family estate in Schweidnitz, Silesia (now part of Poland) and when there, enjoying a few days of hunting wild boar before returning to the Western Front in June.

Albatros D.III fighters of Jastas 11 and 4 lined up at Roucourt in March 1917 with Von Richtofen's crimson colored aircraft, “Le Petite Rouge” visible second from the camera.

Though the Canadians had taken Vimy Ridge and had collapsed the front line near Arras, the Germans never saw it as a major setback, choosing to leave the ridge in Allied hands until the end of the war. Throughout that April however, the Germans had dealt British air operations a bloody nose all along the Arras front. Hundreds of Allied aircraft were shot down in the four weeks of April alone — many by pilots flying the new Albatros D.III and employing their newly-developed Jasta tactics. In all, units of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service lost a staggering 245 aircraft on the Western Front in April. Richthofen was personally responsible for nearly 10% of that total count — 21 aircraft shot down, 23 men killed, eight men now in German PoW camps and seven men wounded in action.

That brought Manfred to his last task before handing over the Jasta to Allmenröder — writing out the inscriptions he wished to have engraved on the small silver trophy cups he liked to have made to commemorate each victory. Unlike boar hunting with its mounted taxidermilogical heads, hunting humans necessitated a less gruesome means of bragging. It’s not known how many of the 21 victories from April he would include in that order, but most likely he handed his adjutant an order to be mailed to the Berlin jeweller with at least the score from the past week — seven aircraft — two lumbering Royal Aircraft Factory (R.A.F.) F.E.2b observation aircraft, three B.E.2 observation R.A.F./bombing aircraft, one SPAD VII fighter and a Sopwith Triplane fighter. Four of those he shot down the day before alone, killing six men, two of which were Canadians. The Sopwith Triplane was the last of these and would be the only Triplane that he would shoot down in his short career.

Richthofen often visited the wreck sites of the aircraft he shot down, and whenever possible, to cut like a scalp the painted serial number from the aircraft out of what remained of the fabric covering for an additional display in his room — a self-promoting exhibit of his skill and ability to ignore the tragedy wrought by his own hands. In fact, he had just that morning visited the wreck site of the SPAD he had shot down the day before.

Photographed in the late 1930s, Manfred von Richthofen’s curious collection of silver and pewter cups commemorating the men he killed The larger drinking cups commemorated each group of ten victims.

A silver cup commissioned by Richthofen to commemorate his 12th Victory was on display in the “Deadly Skies” exhibit at the Canadian War Museum in 2017 — 100 years after the capture and imprisonment of Number 12 — Lieutenant Benedict Hunt of 32 Squadron. Richthofen assumed he had shot down Hunt in a Vickers Gunbus, but in fact it was an Airco D.H.2, an aircraft of similar pusher configuration.

The cups were tiny, so the inscriptions were short — simply the number of the victory, the type of aircraft destroyed and the date of the victory. There were no names of the men he killed and likely he never gave them more than a second thought, though one hopes he would have filled the cup with schnapps upon delivery and made a toast to the unknown airmen he had dispatched. By the time of his death, Richthofen had downed 80 Allied aircraft, but his collection of smaller silver cups stopped at 60 due to silver shortages. After each ten victories, he had a larger cup made to commemorate the accomplishment. In the end he displayed 67 engraved cups — a macabre exhibit of his hunting prowess and martial ego.

This is the story behind the cup with the inscription “52 — Sopwith Triplane - 29. 4. 17.”

Each of these numbered cups was more than just a date or the name of an aircraft type. They represented flesh and blood, young men of exceptional courage and intelligence. Men with the kind of mind and sense of adventure that would keep them out of the mud and trenches… only die perhaps an even more terrifying death. They were the sons of Commonwealth mothers, friends and lovers, athletes and heroes, students and farmers, old boys and colonials, some boastful, most humble. Each had a family on the home front staggering under the grief of their loss. Some of the families had yet to be informed that their sons or husbands had died to line the shelves of the “Red Baron’s” curio cabinet. Everyone had heard of the “Red Baron”. Some had even heard of his grim collection. Few had heard their names. Each one of them deserve a more fulsome story than that engraved on Richthofen’s silver cups.

Richthofen’s No. 52 was a young man from Ottawa, Ontario Canada named Flight Sub-Lieutenant Albert Edward Cuzner. “Eddy”, as he was called by his friends and squadron mates, was a fighter pilot of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). While the RNAS’s core operational work was reconnaissance and anti-submarine work in support of Royal Navy sea operations, it did maintain several fighter squadrons on the Western Front.

Eddy was the son of a hardware merchant in the ByWard Market neighbourhood of the city. The Cuzners had been in the Ottawa area since the building of the Rideau Canal in 1832 — the first known Cuzner being James Cuzner who emigrated from Frome, Somerset, England. He brought his family with him — sons Lucas, John, and Mark and toddler daughter Caroline. Another daughter, Susan, was born in Ottawa in 1836. A contemporary poem by Willian Pittman Lett, an Irish Canadian journalist, bureaucrat and poet implies that John Cuzner as a Royal Navy sailor (tar) and that his brother Lucas (Eddy’s grandfather) was somewhat of a fearsome fellow:

… Close by “the Creek,” on the south side of

Rideau street, did then reside

John Cuzner, a British tar

For pluck renown’d both near and far!

Nor would I willingly forget

While tracing recollections met

For cause as small, and launch’d afar

The fierce and fiery bolts of war,

Simply to find out which was best.

Caesar or Pompey by the test.

Luke Cuzner always had his share.

For Luke in days of auld lang syne

Did most pugnaciously incline,

Never to challenge slack or slow,

And never stained by “coward’s blow.”

The ByWard Market (named after Colonel John By, the British Army engineer who oversaw the building of the Rideau Canal) was a rough and tumble market neighbourhood where local farmers came to sell their livestock, fruit and vegetables. The streets were wide to accommodate carriages, haphazard farm stalls, tethered horses and crated animals. Here you could get your rabbits and poultry slaughtered while you waited, buy fresh vegetables from Ottawa Valley farms or purchase new tack for your horse and carriage. The shops were rough and crowded — the haunts of green grocers, sausage makers, butchers, bakers, tinsmiths, sign painters, news agents and publicans. The place reeked of horseshit, urine, tobacco and pine. It rang with the clop of horses, steel wheels on stone, the crowing of cockerels, the squeal of pigs and shouts of men. Women in dusty Victorian skirts shopped for their families. Children gawped at the slaughtering of chickens and geese and urchins ran off with stolen fruit.

A scene of Ottawa’s Byward Market from the late 1800s. The McDougall and Cuzner Hardware store was just off to the right of this photo.

An illustration for an Ottawa newspaper depicting the northeast corner of Sussex and George Streets celebrating the Canadian Academy of Arts Exhibition in the four storey Clarendon Building. In the background at left are the letters McD & C STOVES painted on the side wall of the building which housed the McDougall and Cuzner Hardware store at 521-23 Sussex Street. Eddy’s father John was the proprietor of this store. The art exhibited here in 1880 formed the nucleus of the National Gallery of Canada’s outstanding Permanent Collection.

The Byward Market sat in the southwest corner of a larger blue-collar neighbourhood known as Lowertown. Though the name Lowertown came from the fact that it was situated below Parliament Hill and Uppertown, it seemed to hint at the economic realities of its denizens — working class families of the Jewish and Irish diasporas and French labourers — the kind of citizen refused entry and membership in the social fortresses of the day — the private Rideau and Laurentian Clubs of Uppertown, and the golf and country clubs on the pastoral skirts of the city core. The Cuzner Hardware Store was on Sussex Street (now called Sussex Drive) which roughly formed the western edge of Lowertown. Sussex was not as posh in the time of the Great War as it is today, but it was more established than the seasonal chaos of the farmers’ market just a couple of blocks to the east. Here the stores had busy, patriotic display windows and high ceilings, drawer and cabinet-lined interiors cluttered with displays, smelling of waxed wood, cigarette smoke and leather and piled with their stock and trade — fedoras, women’s fashions, hunting and fishing supplies, liquor, horsehair-stuffed chesterfields, wallpaper, riding boots and cigars. Sussex was the 1916 version of a shopping mall.

Cuzner Hardware — 125 Years in Ottawa and the Valley.

The Cuzner family’s hardware business was originally named McDougal Hardware. McDougal began his business on Sussex Street but later had a store at the corner of Lett and Queen Street West in LeBreton Flats (this would later move to the corner of Duke and Bridge in LeBreton), an area of Ottawa known for its working-class row housing, lumber storage yards and light industry — foundries, paintworks, breweries, machine shops, wood milling factories and electrical works. John Cuzner, James’ son, worked for McDougal and eventually bought into the business. Francis McDougal, Cuzner’s partner in the businesses went on to become mayor of Ottawa from 1985 to 1986. A feature article on the new mayor of Ottawa which ran in the Ottawa Journal on Dec. 31, 1886 stated:

Some years ago he established a branch store at “Le Breton’s Flats,” now Victoria Ward, and another at Mattawa, both of which enterprises have been successfully prosecuted to the present. A few years ago he entered into partnership with Mr. John Cuzner, a young man of steady and active business habits, who had been in his employ from early boyhood.”

It was here in Ottawa in 1850 that Eddy’s father William John Cuzner was born, the grandson of James Cuzner of Frome. In addition to the Sussex Street and Lebreton Flats stores they operated a branch store in Mattawa, Ontario, some 300 kilometres to the northwest of Ottawa.

A photograph dating to August of 1898 shows the McDougal and Cuzner Hardware company store in Ottawa’s Lebreton Flats neighbourhood which was originally located at the corner of Duke and Bridge Streets. It was burned to the ground a year after this photo was taken along with the entire neighbourhood in the Great Fire of 1900 which swept through the lumber storage yards of the Flats and consumed part of Hull and Lebreton all the way to Dow’s Lake. The store relocated to 40 Queen Street West, next to the City’s Fleet Street Pumping Station. It remained there until new premises could be built one block west at the southeast corner of Queen W. and Lett Streets (No. 60 Queen W.), where it remained for decades along with the Sussex location.

A view from the 1920s looking southwest along Queen Street West. Duke Street is at right as is the car sheds of the Ottawa Electric Railway. The building at left with the painted sign touting DODGE SPLIT PULLEYS AND MILL SUPPLIES is the third McDougal and Cuzner store in the neighbourhood (no. 60 Queen W). The first was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1900 and the second temporary one was just a few doors to the left of this photo frame at 40 Queen W.

In 1958, the building which housed Cuzner Hardware on Sussex Street suffered heavy damage in a fire that started in the kitchen of the Sussex Grill restaurant on the ground floor and spread through the ventilation system. It was a tough pill to swallow after the recent death of Eddy’s brother Willard who had run the store since 1902. The driving force behind the Cuzner Hardware enterprise had diminished drastically, and in February of 1960, Cuzner Hardware surrendered its charter and ceased to exist. Image via Newspapers.com

After the fire, Cuzner Hardware left the premises and its new tenant, Hobby House, another iconic business, opened for business on May 1, 1959, but vacated in 1964.

The 521-523 Sussex Street location of McDougal and Cuzner Hardware (Later Cuzner Hardware) was a much-loved address in Ottawa’s Baby Boomer history as the home of internationally known Le Hibou Coffee House. It began operating as early as 1960 on Bank Street but made the move to Sussex in March 1965. It was in these historic Cuzner store premises that such music icons as Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Neil Young, Gordon Lightfoot, John Prine, Leonard Cohen, John Lee Hooker, Tom Rush, Jesse Winchester, Taj Mahal, Buddy Guy, Kris Kristofferson and hundreds more performed for the Beat and Baby Boomer generations. Visiting performers like Jimi Hendrix and George Harrison performing at larger Ottawa venues could often be seen at after-hours concerts at Le Hibou.

Eddy was born in 1890. He was the second A. E. Cuzner in the family. An older brother, Alfie Edward Cuzner, was born in 1883, but died just a couple of years later. Eddy had another older brother named Willard, a younger brother named Ivan who died at age 5 months, and two sisters named Eileen and May. For a time, the Cuzner family lived in Lowertown at 157 Augusta Street, the second door from the left of a six-door row house, just a few yards from Rideau Street, Ottawa’s main artery at the time. It seems that they moved later as Eddy’s father died of acute rheumatism at home in 1907 when Eddy was still in high school. According to newspapers, the family was living at that time at 20 McKenzie Avenue, just a block west of their Sussex Street hardware store.

McDougal and Cuzner Hardware’s success meant that eventually they did not have to continue to live in the busy clamour of Lowertown and Eddy’s mother and sisters took up residence in the newly developing Ottawa suburb known as The Glebe. She lived there with the rest of the family on First Avenue. Following his father’s death, Eddy’s brother Willard took over management of the Sussex store in 1909 and became the de facto head of the family.

Growing up sportsmen — the hunter and the footballer

While Manfred von Richthofen was from a prominent aristocratic Prussian family and carried the title of Freiherr (literally “Free-Lord or Baron), it was Eddy Cuzner who was the most educated of the two. Manfred was initially homeschooled by tutors and then briefly attended an elementary school in Schweidnitz where the family’s estate was located. At the age of 11, he was enrolled in Königlich Preußische Hauptkadettenanstalt (Royal Prussian Cadet Institute) where he learned the bearing, arrogance and skills of a Prussian cavalry officer. He enjoyed the manly pursuits of aristocracy — horsemanship, wild boar hunting and the collecting of trophies.

Across the Atlantic at the same time, young Eddy was being educated at Ottawa Model School— a practical training elementary school attached to the Ottawa Teachers' College (also known then as the Normal School). It was used to give teachers hands-on experience with live students and was located on the grounds of the Teachers' College at the corner of Lisgar and Elgin Streets. The school building is still there today. Following elementary school, he attended Ottawa Collegiate Institute, one of only two English-speaking high schools in Ottawa at the time, now known as Lisgar Collegiate Institute (the other was Kent Street School). Eddy played senior rugby football with the Lisgar team and stood out as a star athlete. He would be one of a more than 130 Lisgar Alumni do die in the First World War.

Following high school, Eddy earned a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Toronto and was studying for a further degree in forestry science when war broke out. Eddy was an outstanding athlete his entire life and met grid iron and hockey fame as a member of the University of Toronto’s Varsity Blues rugby football and hockey teams. His name appeared weekly in the sports pages of the Toronto Star. By 1913, however, serious knee injuries forced him off the playing field and ice rink to become Assistant Manager of the Varsity Blues Firsts Rugby team in 1913 and by 1914, he was also manager of the Seconds Hockey team.

When war broke out, Eddy wanted to get overseas but also wanted to fly. One way to guarantee that would happen would be to arrive in England with flying experience under his belt and a Royal Aero Club card in hand. In 1916, he left his studies in the Forestry Department and joined a flying training program at the newly created Curtiss Flying School which was training young Canadian men to become pilots for the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and Royal Flying Corps. The Longbranch aerodrome where this was carried out was Canada’s first official aerodrome and was managed by none other than Canada’s first aviator J. A. D. McCurdy of Silver Dart fame. The training syllabus included initial instruction on Curtiss Model F flying boats based at Hanlan’s Point on Toronto Island and so-called “advanced” training and solo flying in Curtiss JN-3s on wheels at the company airfield in Longbranch (located west of Toronto, Ontario and just east of Port Credit, now Mississauga).

A 1912 photograph of the University of Toronto Rugby Varsity Blues team superimposed on a modern photo of the same doorway at University College building at 15 King's College Circle, Toronto. Eddy Cuzner is circled in red. A year later, his injuries had forced him into a managerial role on the team.

After suffering career-ending knee injury, Eddy Cuzner remained part of competitive varsity spots at the University of Toronto — as Assistant Manager of the rugby team and later as Manager of the U of T ice hockey team.

Students were required to cough up their own tuition money — $400 ($50 with submission of an application and $350 upon acceptance into the program). A promise was made to students that if they were successfully complete the course, receive their licences, the British government would refund $375 of the total fee. The total flight time instruction was to be 400 minutes (6.5 hours!) but the RFC and RNAS were pressing the school to send over students before the end of training in order to complete their flying instruction in Great Britain for immediate service on the front lines. The Toronto newspapers in the summer of 1916 reported that students were worried that since they had not received their licences before going overseas, they were not going to get their promised refund.

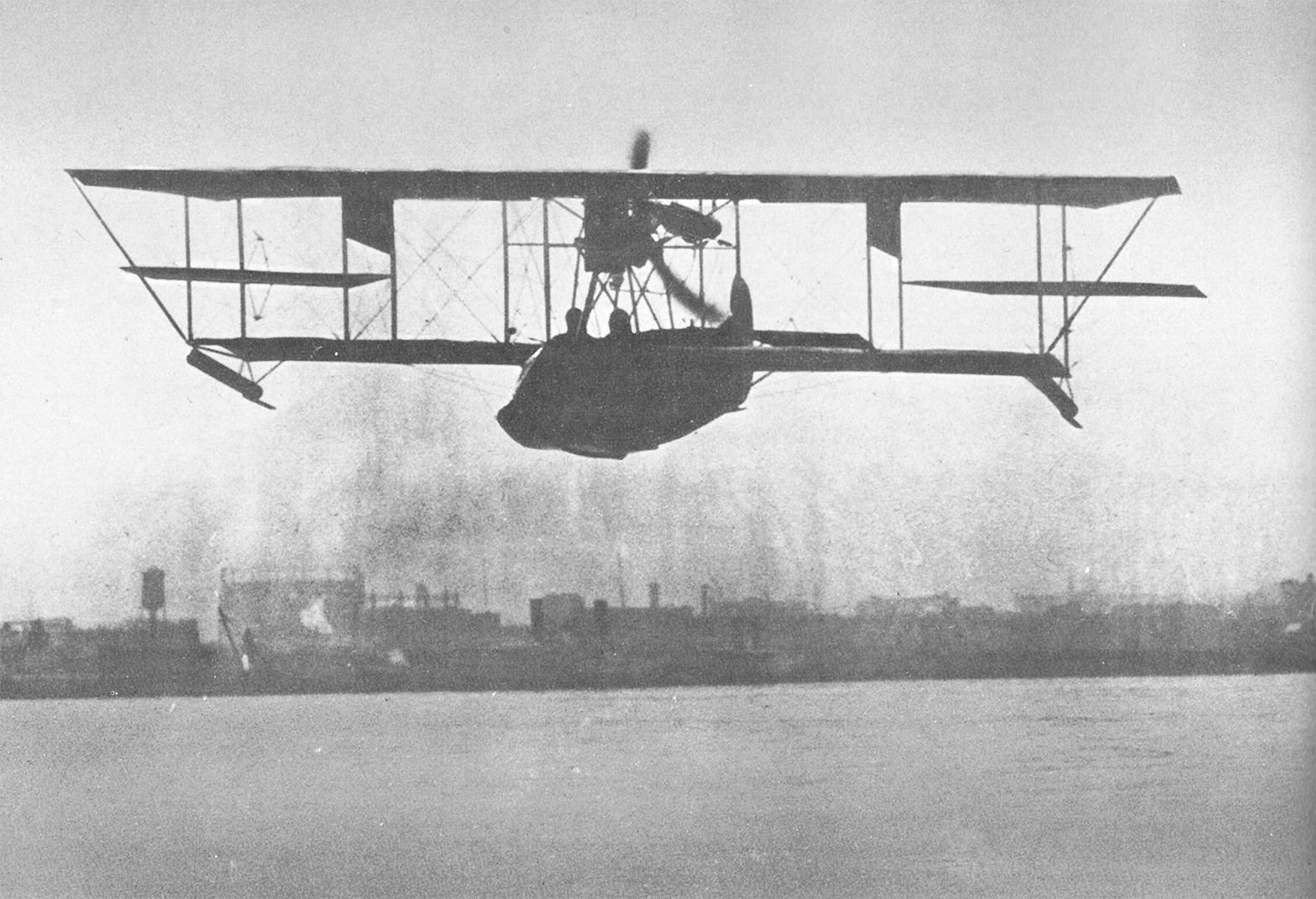

A Curtiss Model F flying boat over Toronto harbour. Eddy Cuzner and fellow pilot trainees began their basic flying training on these slow-moving flying boats operating from Hanlan’s Point Beach near today’s Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport. Even as early as 1884, part of Hanlan’s Point Beach was reserved for nude bathing — the world’s first municipally sanctioned nude beach.

A pilot of the Curtiss Flying School at Longbranch, Ontario (now Mississauga area) get ready to fire up his Curtiss JN-4 Canuck in October of 1915. This is the type of aircraft Eddy flew and the time of year that he took instruction. Photo via Harold Skaarups www.silverhawkauthor.com.

Eddy Cuzner did in fact complete his Curtiss School syllabus and receive his Royal Aero Club certificate (No. 3627) on September 3, 1916. He then travelled home to Ottawa to say farewell to family with another Curtiss flying trainee by the name of Cecil John Clayton (R.A.C. Certificate No. 3629) from Victoria, British Columbia. It was in Ottawa that both men enlisted in the Royal Naval Air Service with a guaranteed paid passage to Great Britain.

After a brief rest and farewells, Eddy and Cecil boarded a train at Union Station in downtown Ottawa bound for Montreal where they boarded S.S. Corinthian, a cargo passenger ship of the Glasgow-based Allan Line, the dominant transatlantic carrier between Canada and Scotland on the 19th century. Corinthian now served as a troopship for the Canadian Expeditionary Force on the Montreal to London route and, since their purchase of Allen Line, was a now a Canadian Pacific ship. Shipping movements, especially troop ships, were kept secret in the First World War for fear of submarine attack, but safe arrivals were well reported. A short notice in the Montreal Gazette on September 13th noted: “The S. S. Corinthian, Captain Tannock, is now entered inward at the Custom House. Consignees will please pass their Entries without delay — Canadian Pacific Ocean Services Limited, Managers and Agents.” S. S. Corinthian was also tangentially involved in RMS Titanic’s fateful voyage in April, 1914 when Captain Tannock requested that an ice report he had received from sister ship S.S. Corsican be forwarded to Titanic.

Eddy Cuzner sailed for Great Britain aboard S. S. Corinthian of the Allan Line (by then merged with Canadian Pacific), arriving in London on September 30, 1916. Corinthian became a part of the Canadian Pacific fleet when CP took over Allan in 1917. On 14 December 1918, Corinthian was wrecked in the Bay of Fundy. There were no deaths, but efforts to salvage the ship were soon abandoned and she was declared a total loss.

After an uneventful crossing of about two weeks (with a stop in Quebec City), Eddie and Cecil Clayton disembarked Corinthian on September 30th, 1917. Corinthian would survive the war only to run aground off Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy coast a month after the war ended. She had sailed from Saint John, New Brunswick at 7:00 am on December 14 (1918) carrying a load of foodstuffs intended to alleviate wartime shortages in Britain. She lost her way in thick fog at the entrance to the Bay of Fundy and at 3:00 in the afternoon fetched up on the Northwest Ledge of Brier Island. The year had been difficult for the Western Nova Scotia and locals went out in boats and salvaged much of the cargo of food which saw them through the winter. The London Times reported that: “As a result of indifferent seamanship, which brought about the loss of their vessel, the certificates of the captain [Tannock—Ed.] and the chief officer of the C.P.R. steamer Corinthian have been suspended for three and six months, respectively.”

Navy Pilot in Training

In early October of 1916 Cuzner and Clayton proceeded to complete a Disciplinary Course for new recruits at H.M.S. President II (Crystal Palace) — a course akin to what young pilot recruits would go though at Manning Depot in the Second World War. From there, they would do further flying training and evaluation in England. It was here that both men were made Probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenants.

For Cuzner and Clayton, six hours of basic instruction accumulated at the Curtiss Flying School just scratched the surface of what was needed. At this time, elementary flying training consisted of 20-25 hours of solo flying at one of four RNAS flying schools — Eastchurch (Kent), Chingford (London), Eastbourne (East Sussex) or Redcar (Yorkshire). For Eddy Cuzner and Cecil Clayton, it was to be RNAS Redcar for this initial phase of assessment and training, starting on November 4th. The aerodrome at Redcar on the Yorkshire coast hosted an elementary flying school for newly entered pilots into the Royal Naval Air Service, though some offensive and defensive operations were flown from there as well. The base was created as part of chain of new air stations after the German naval bombardment of east coast towns in December of 1914. Instruction here was on the fragile looking Caudron G.3.

Life for a raw recruit in basic training at Crystal Palace was not for someone seeking privacy as witnessed by these endless rows of hammock sleeping accommodations. Photo: Imperial War Museum

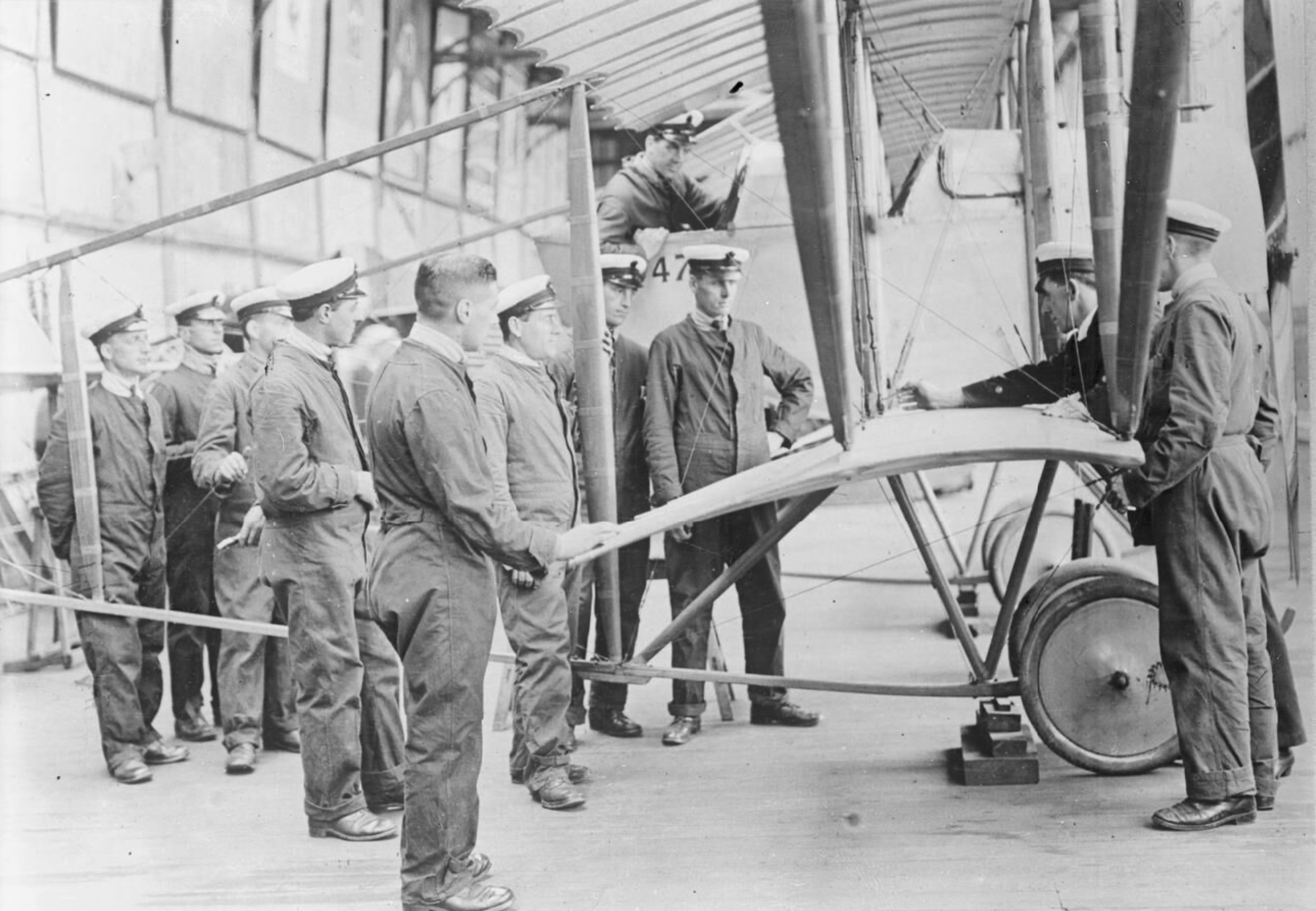

Probationary Flight Sub Lieutenants get a beginner’s lesson on the Caudron biplane at Crystal Palace. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Cuzner and Clayton took further primary flying instruction at RNAS Redcar on the ungainly Caudron G3, a French-designed and built sesquiplane used by the British early in the war on the battlefront when supply of British-made aircraft was not yet up to speed. It was nicknamed “Cage à poules” by the French for its resemblance to a wire chicken run. The Caudron in this photo, a Belgian example restored in the markings of RAF serial number 3066, still exists today, on display at the RAF Museum in Hendon. Caudron 3066 was an aircraft flown by RNAS students at RNAS Flying School Vendome in France Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Caudron in this image, a civil-registered post war example, shows the cockpit and instructor/student configuration. This aircraft (F-AFDC) exists today on display at The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History in Brussels, Belgium.

Following this, Cuzner and Clayton ended up together at Central Flying School at the newly commissioned RNAS Cranwell in Lincolnshire for their advanced training on the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c. By 1917 the B.E.2c had been relegated to training services because its relatively poor performance against more advanced German fighter aircraft. This performance earned it the nickname “Fokker Fodder” by its pilots and “Kaltes Fleisch” (Cold Meat) by their German adversaries. Later variants of the B.E.2c like the e-model were still operational on the Western Front but were no better than the trainers Eddy was flying.

At Cranwell, Cuzner and Clayton earned their pilot’s wings flying the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c

Following wings parade at Cranwell, Clayton was posted to RNAS Calshot near Southampton where he took instruction on Felixstowe F5 flying boats ending the war with a Distinguished Flying Cross and as deputy commander of Royal Air Force Station Felixstowe where the Royal Navy’s Seaplane Experimental Station was situated. He continued to fly flying boats in Canada until the early 1920s and then went into dentistry, though he spent his school summers flying forestry protection patrols in Quebec and Ontario with Laurentide and Ontario Provincial Air Service. He practiced dentistry in Rainy River, Ontario, and Victoria, where he died in 1965.

Aerial view of RNAS Station Calshot where Clayton completed his training on flying boats. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Clayton went on to further training on the Felixstowe F.3 military flying boat at Calshot. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Eddy graduated from his flying course at Cranwell with his new pilot’s brevet on February 21st, 1917. Here it is recorded in his available service record that he had amassed only 22 3/4 hours flying time. This likely does not include the six hours he received in Toronto. Three weeks later on March 8, after a break, he was posted to Royal Naval Air Station Dover at Guston Road, likely to take passage to France.

Eddy went straight from his leave to No. 8 Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service arriving on March 16th — there to learn on the job how to fly and fight the nimble Sopwith Triplanes that No. 8 had just acquired in the last weeks of February. The squadron had been based since October from the aerodrome in Saint Pol-sur-Mer on the outskirts of Dunkerque on the northwest flank of the battlefront near Ypres. The squadron had continued operations at “St. Pol” through February 1917, eventually transitioning there from their Sopwith Pups and Nieuports to the new, more agile “Tripes” (as pilots called them.) At St. Pol, there was also a French Navy squadron — Escadrille de Chasse Terrestre du Centre d’Aviation Maritime de Dunkerque which also operated Sopwith Triplane scouts to protect both the Dunkerque station and French bombers operating in the area. In March, the squadron moved to the centre of the front line in the Arras-Vimy area and took up residence at the Auchel aerodrome in the heart of the French and Belgian coal-mining region. It was here that Eddy joined the squadron.

No. 8 RNAS reformed at Saint Pol-sur-Mer in February of 1917, the year this aerial view of the aerodrome was taken. This was no rough and ready airfield at the front, but rather a large and permanent air base.

The Auchel region of northern France was, for the better part of a century, an industrialized coal-mining area where giant slag heaps made from the waste from coal mining and known as “terrils” rose to massive heights on the otherwise flat plain of the Pas-de-Calais “Département”. The Mining Basin is a now UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The immaculate figure of “Canada Bereft” stands on the massive podium of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial near Arras. Far in the distance we can see the “terrils” or slag heaps of the Pas-de-Calias Département where Eddy Cuzner’s No. 8 operated during his brief war.

The Sopwith triplane was ordered in quantity by the Royal Naval Air Service and used almost exclusively by that service. Richthofen commented that the Triplane was the best Allied fighter at that time, a sentiment that was echoed by other German senior officers such as Ernst von Hoeppner. Several examples were captured and assessed and in a matter of months resulted in the design of the Fokker D.I, the triplane with which Richthofen would eventually and forever be associated. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The triplane’s stack of wings was an impressive sight giving it plenty of climb and maneuverability. Like many of contemporaries, it was surprisingly small, measuring about 19 feet long with a 26-foot wingspan. During late 1916, quantity production of the type commenced in response to orders received from the Admiralty. During early 1917, production examples of the Triplane arrived with Royal Naval Air Service squadrons like Cuzner’s No. 8 which first took delivery in March, 1917. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A Quick Look at the back end of a Triplane shows us that it had ailerons on all three wings, giving it extraordinary maneuverability. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Bloody April

While April, 1917 was a month of great Canadian successes on the ground on the Western Front and is looked upon as a high point in Canadian participation in the First World War, it was the costliest month of the entire war for the airmen of the Royal Flying Corps and their brothers in the Royal Naval Air Service. The RFC suffered 245 aircraft lost, 211 aircrew killed or missing and 108 taken as prisoners of war. Against this terrible outcome, the German air service lost just 66 aircraft. Factors contributing to the heavy losses included the RFC's use of obsolete aircraft like the B.E.2, a lack of superior fighter aircraft, and inexperienced pilots facing the superior German Albatros D.III fighters, a situation exacerbated by poor pilot training and aggressive British tactics.

The German Air Service, particularly the specialized fighter units known as Jastas (Jagdstaffeln), had achieved a significant technological advantage with advanced fighter aircraft like the Albatros D.III. Many RFC units were still flying outdated and vulnerable aircraft, such as the B.E.2, which was stable and suitable for reconnaissance but slow, underpowered, and had poor maneuverability, making it easy prey for German fighters.

Under the command of Major-General Hugh Trenchard, the RFC maintained a continuous offensive stance, conducting vital aerial reconnaissance and artillery spotting missions over German lines despite the heavy losses. This led to daily engagements in unfavorable conditions. Many new RFC and RNAS pilots arrived at the front with insufficient flight experience and minimal combat training, with the average life expectancy of a newly arrived airman dropping to as little as 11 days during this period.

Eddy Cuzner had the misfortune of arriving on the Western Front just two weeks before April and with brutally insufficient training — just 30 hours of aggregated flying time, much of it with an instructor aboard. With, for all intents and purposes, no combat training, he was lucky to have survived the entire month… at least he almost survived

Smiling Manfred von Richthofen, the Commander of Jasta 11, surrounded by his fellow pilots and his dog Moritz, at Roucourt, France in April 1917. These five men alone took an enormous toll on the RFC and RNAS in the month of April — Left to right: 81 Allied aircraft!! Sebastian Festner (nine victories that month, killed on 25 April), Karl-Emil Schäffer (fifteen victories), Manfred von Richthofen (21 victories), his brother Leutnant Lothar von Richthofen (fifteen victories) and Leutnant Kurt Wolff (21 victories). Photo: Imperial War Museum

Richthofen, second from left introduces some of his Jasta 11 pilots to Generalleutnant Ernst Wilhelm Arnold von Hoeppner, the Commanding General of the Imperial German Air Service (Luftstreitkräfte) at Roucourt, France on April 23, 1917 — just 6 days before Richthofen shot down Eddie Cuzner. Hoeppner was there to congratulate Richthofen and his pilots on their recent victories against the British in what became know as “Bloody April” to the pilots of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service. Photo via www.masnystoria.fr

Richthofen’s bloodiest day

There was a lot of aerial activity along the Western Front on Monday, April 29, 1917. The day was clear and the temperature hovered around 20 degrees Celsius. It was a good day for hunting. On the German side of the front, Jastas 5, 11 and 12 were busy all day while on the Allied side of the trenches, 12, 18, 19, 56 and 57 Squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps readied their aircraft at dawn. Royal Naval Air Service Squadrons 1, 3 and 8 did the same. By end of day, however, more than 20 British aircraft would lie in smoking ruin on the battlefront, almost a third of them brought down by the Richthofen brothers Manfred and Lothar.

In addition to celebrating his victories with a commemorative silver cup, Richthofen enjoyed visiting the crash sites of his victims to cut out the serial number from the sides of the wreckage. This scalp-taking tells us a lot about how he viewed the men he killed. Since all of the serials in this image are from aircraft he shot down in April 1917 or before, there’s a good chance this was his room at the Chateau Raucourt.

Shortly after noon that day, flying his all-red Albatros D.III “Le Petit Rouge”, Manfred Richthofen led Jasta 11 high over the LéCluse area, halfway between Lens and Calais in search of easy targets like British and French reconnaissance or bomber aircraft. Instead they were attacked by a patrol of three SPADs from 19 Squadron, RFC with the ironic sobriquet: “The Chosen Squadron”. During the ensuing dogfight, two of the three SPADs were shot down with Richthofen bringing down a SPAD VII, piloted by Wiltshire-native Lieutenant Richard Applin of the Royal Flying Corps. A merciless Richthofen’s memoir states:

My man was the first who fell down. I suppose I had smashed up his engine. At any rate, he made up his mind to land. I no longer gave pardon to him. Therefore, I attacked him a second time and the consequence was that his whole machine went to pieces. His planes dropped off like pieces of paper and the body of the machine fell like a stone, burning fiercely. It dropped into a morass. It was impossible to dig it out and I have never discovered the name of my opponent. He had disappeared. Only the end of the tail was visible and marked the place where he had dug his own grave”

About five hours later, on another patrol that same say, Richthofen was leading his flight of Albatros D.IIIs southwest of Inchy when he attacked a hapless, lumbering F.E.2b of 18 Squadron, an obsolete two-seater assigned to protect reconnaissance aircraft with a gunner in the nose firing one or two Lewis guns. The aircraft, crewed by two teenagers — Sergeant George Stead with gunner/observer Corporal Alfred Beebee — never had a chance. Stead was 19-years old, was married and had just become a father eight weeks previously. Corporal Beebee was even younger at 18, having enlisted under-age. Neither man’s body was recovered and they have no known grave.

Two and half hours later, at around 7:25 PM, Richthofen along with Lothar and Jasta 11 were on their fourth and last patrol of the day, when, five kilometres west of Arras between Roeux and Monchy-le-Preux, they came across a pair of Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2es of 12 Squadron, the same type of obsolete and underpowered aircraft that Cuzner and Clayton had trained on in just a few weeks earlier. The B.E.2e was a sesquiplane development of the 2c but, though expected to be a great improvement on the "c", it was a major disappointment. The two were on an artillery spotting mission when they ran into Jasta 11. Manfred attacked one of the two aircraft — piloted by Second Lieutenant David Evan Davies with a Canadian, Lieutenant George Rathbone of Toronto, as the observer/gunner. Lothar took on the second. As Manfred would later relate,

At 1925 hours, near Rouex, this side of the lines. Together with my brother, we each of us attacked an artillery flyer at low altitude. After a short fight my adversary’s plane lost its wings. When hitting the ground near the trenches near Rouex, the plane caught fire.”

As with all of the 6 men Richthofen shot down that day, their bodies were never recovered, and they have no known grave.

Richthofen’s flight of eight Albatros scouts then turned north toward Lens. Around 8 kilometres northeast of the present-day site of the Vimy Memorial, they engaged a mixed group of Sopwith Triplanes, SPADs and Nieuports.

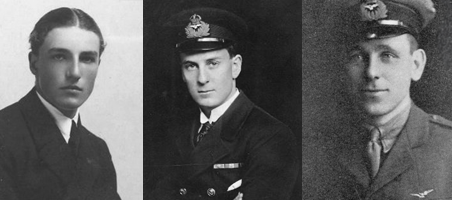

No’s 49, 50, 51 and 52 of Richthofen’s silver cup collection were young men from England and Canada. I was able to find photos of five of them: Left to right: Richard Applin, George Stead, Alfred Beebee, George Rathbone and Eddy Cuzner. In all that day, Richthofen sent 6 young men into oblivion, for their bodies were never found and none have a known grave.

Eddy’s 16th and final combat patrol

Eddy had now been a combat scout pilot for six weeks. Following a period of Triplane training and familiarization with the front lines, he now had 15 combat patrols under his belt. He was by no means an experienced veteran, but neither was he a total greenhorn. According to Jon Guttman, in “Naval Aces of World War 1” (1975), Eddy took off from Auchel that evening at 1720 hrs in the company of five other Naval 8 pilots, all of whom would truly distinguish themselves on the Western Front.

The flight of “Tripe Hounds” was led by Commander Anthony Rex Arnold, DSC, DFC, an ace by war’s end with five victories. With him were the Australian Flight Sub-Lieutenant Robert Little, DSO and Bar, DSC and Bar who claimed 47 victories before his death a year later; fellow Canadians Flight Sub-Lieutenant Rod McDonald who would also perish a year later, with 8 victories and A. R. Knight of Collingwood, Ontario; and Flight Sub-lieutenant Philip Andrew Johnston, another Australian, with 6 victories (by end of his war) who would die in a combat-related air-to-air collision the following August. Both Cuzner and McDonald had arrived on squadron the same week, so were likely not leading.

Eddy was in Triplane N5463 with the name “DORIS” written on its fuselage. Based on the aircraft they were often associated with, Little was likely flying his N5493 with the word 'BLYMP” (his nickname for his infant son) emblazoned; McDonald in his N6301 “DUSTY II”, Arnold in N6290 “DIXIE”, Johnston in N5449 “BINKY III”.

Sopwith Triplanes of No. 8 (Naval) Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service, in France. The aircraft nearest the camera (N5468 — ANGEL) is just five airframes on the Sopwith assembly line from Triplane 5463 Doris which was flown by Cuzner when he was caught by Richthofen. Pilots of Naval 8 were encouraged to paint the names of their sweethearts or family members on their Triplanes — names like Dusty, Dixie, Hilda and Doris. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A finely detailed model of Sopwith Triplane N5463 by model builder Oleg in Zaporizhzhya, Ukraine in 2012. Oleg’s work can be seen in its entirety here. Photo via Aeroscale.net

Three of the five scout pilots who took off with Cuzner that day. Left to Right: Flight Commander Anthony Rex Arnold DSC DFC; Flight Sub-Lieutenant Robert Alexander Little, DSO & Bar, DSC & Bar and Flight Sub-Lieutenant Roderick McDonald of Nova Scotia who also started at the Curtiss Flying School at Longbranch.

Around the same time that Richthofen had sent Davies and Rathbone spinning down to their deaths, Eddy Cuzner was prowling the skies near Vimy Ridge with the other Naval 8 Tripes, looking to take down some German aircraft to try to even the “Bloody April” score. They were in the company of SPADs and Nieuports from the Royal Flying Corps.

Once Jasta 11 formed up after engaging the two B.E.2es, they headed north towards Lens. Their Fokker D.IIIs climbed to meet an enemy formation of Sopwith Triplanes, SPADs, and Nieuports spotted in the area east of Lens which Richthofen described as “a strong enemy single-seater force”. Richthofen would later write this truly arrogant account:

“We flew on, climbing to a higher altitude, for above us some of the “Anti-Richthofen Club” had gathered together. Again we were easy to recognise, the sun from the west illuminating the aircraft and letting their beautiful colour be seen from far away. We closed up tightly, for each of us knew we were dealing with “brothers” who pursued the same trade as we did. Unfortunately they were higher than we were, so we had to wait for their attack. The famous Triplanes and SPADs were new machines, but it is not a matter of the crate as much as who sits in it — the “brothers” were wary and had no spunk.”

According to Guttman, the Triplanes did in fact descend and engage the “Albatrosen” of Jasta 11, but in doing so, their formation broke up. Eddy Cuzner, having lost his height advantage, soon found himself with a red Albatros D.III on his tail. At some point in the 30-minute whirling dogfight that followed contact, Eddy Cuzner’s Triplane disappeared.

When the others of Naval 8 returned to Auchel that evening none had an idea of what had happened to him. Edward Crundell, who kept a diary, wrote in 1975 that “In the evening Cuzner went on patrol and did not return. Nobody knows what happened to him so he has been posted missing.”

There was, however, one person who had witnessed what happened to Eddy: Manfred Richthofen. The Sopwith Triplane that he had latched onto near Lens was his first (and eventually only) of the type and he surely pressed his attack even harder. Firing his twin Spandau machine guns, he set Eddy’s machine on fire and it spun to the ground near Hénin-Liétard, 15 kilometres northeast of Vimy. It was his fourth victory of the day, his best one-day tally of his career. His brother Lothar had also had a banner day. Manfred would later write glibly that “Both brothers had shot down six Englishmen in one day,... I believe the English were unsympathetic toward us.”

It’s really impossible to know for sure what happened to Eddy. Even Richthofen, who wrote about it, did so months later. In 2017, R. Gannon, a frequent contributor to the aerodrome.com forum wrote this well-reasoned theory of Cuzner’s fate:

“… on the balance of the evidence it would appear that his triplane crashed to earth south-west of Billy-Montingy. Pointedly Billy-Montingy is barely 3km north-west of Drocourt, which was where FCdr Arnold dived on the five [red] Albatros at 18.40BT/19.40GT, strongly suggestive that FSL Cuzner met his end at this very juncture between Drocourt and Billy-Montingy and not as the result of some prolonged pursuit by MvR over Lens (8km to the west). An interesting window is provided by FSL Little, who in attempting to catch up with his flight was flying on the same level as the five red Albatros and reported, ‘I observed Flight Commander Arnold dive down on them to about 6,000 feet and then lost sight of him…’ However, drawing upon Richthofen’s accounting in his book where he asserts two Englishmen dived on his formation one after the other, one might wonder as to whether FSL Little’s impression that the said triplanes was flown by FCdr Arnold was derived from speaking with his flight commander after the mission and for all we know he could have witnessed the triplane of FSL Cuzner which instead of climbing away as per FCdr Arnold – simply disappeared (8 Naval triplanes did not have distinctive identification numbers or letters). Ergo: Albert Cuzner had likely followed FCdr Arnold down in the attack upon the five red Albatros at 6,000ft and instead of zooming, his triplane continued down; plausibly because it was in the process of folding up with the remains crashing to earth between Drocourt and Billy-Montingy.”

Eddy must have given him a real fight though, for Richthofen was pressing for a triplane of German design to counter its performance within days. In “Sopwith Camel VS Fokker Dr.I, Western Front 1917-18” Jon Guttman wrote that “the scout’s performance left enough of an impression for the influential Baron to join the clamour for a new fighter to counter it.”

A painting by Tom La Padula depicting the death of Eddy Cuzner and the only time that Richthofen claimed a victory over a triplane. La Padula will soon publish a book with paintings of each of the aerial victories of the Red Baron, of which this is one. His book, The Red Baron's Kills An Illustrated Portrayal of Manfred von Richtofen's Victories will be released in the July, 2026

An image which purports to be of the wreckage of Cuzner’s triplane shows up on several locations — Canadian Virtual War Memorial and Ancestry.com. It’s hard to source proof of this and the sign in the background shows two crosses leading me to wonder if this is the wreck of a two-seater. As well, Eddy Cuzner has no known grave, yet it is clear from the sign that at least one body was being memorialized. For someone to take the time and effort to make the wood marker and then have a photo taken, it is, in my opinion, likely they also buried the airman or airmen and recorded the grave. As well, it’s possible we are looking at the motor at the far right of the wreckage pile and the silhouette of the cylinders does not appear to be that of a nine-cylinder Clerget 9B Rotary which powered the Sopwith Triplane.

When the whirling dogfight ended, Richthofen in “Le Petit Rouge” made a few hand signals, gathered his “circus” and led his Jasta on the continued hunt, and then eventually home to Roucourt, some 25 kilometres southeast from Lens. It would be the last time he would fly the Albatros “Le Petite Rouge”. Somewhere behind him the wreckage containing the body of Eddy Cuzner, star athlete, Varsity Blue, and forestry science student, burned furiously, the smoke rising and drifting on the wind across the devastated landscape. Given the location of the site, there were most certainly witnesses on the ground, yet Eddy’s body has no known grave. It’s possible everything was consumed in a fire including Eddy’s remains and soldiers on the ground were reluctant to collect him. It’s also possible that his body was removed, buried and then lost to recorded history, a common occurrence when artillery wrecked grave sites. We will never know. His fate and his death were not witnessed by his comrades. We do know that Richthofen did visit the crash site of Richard Applin near Lécluse to collect a souvenir. This was only 10 kilometres southeast of Roucourt. Given the early evening return to base on the 29th, this visit was probably on April 30th. It’s unlikely he took the time to find and visit all four sites of his previous day’s victories as they were spread out and he likely had some paperwork to finish before heading for Germany and a lengthy leave.

Back home, his 31-year-old brother Willard, now running the family hardware store on Sussex Street, was informed by transatlantic telegram from the Admiralty that Eddy was missing. As with every family, the news came as a shock, given that a couple of weeks before he had received a letter from Eddy stating that he was happy and in his usual good health and that he had flown scouting duty in his Triplane in the battle for Vimy Ridge. The battle, in which nearly 100,000 Canadians were involved and 3,600 had been killed as well as 7,000 wounded, had been the biggest war news to date for Canada’s small 8,000,00 population. Everyone across the country had heard the news of the victory for the Canadian Corps and were extraordinarily proud of anyone involved in taking the ridge that the Germans had held for so long.

A brief news report appeared in the Ottawa Evening Citizen on May 19 in which Eddy was described as “well known and popular”. The article wrongly stated that Eddy had been at the front for 18 months which was as far from the truth as one could imagine since Eddy had been there only six weeks. There was no news of Eddy’s fate until a death notice appeared in the Ottawa Citizen on Christmas Eve, 1917 which ended with three haunting words: Somewhere in France.

Then in two weeks later on January 11 of 1918 came a bit more detail when another short piece appeared in The Ottawa Citizen”

“LT. ALBERT CUZNER KILLED IN ACTION. Ottawa Flyer Had Been Missing Since April Last

After a suspense [sic] since last April, Mr. Willard W. Cuzner of 35 Aylmer Avenue has been recently notified that his only brother, Lieutenant [sic] Albert Edward Cuzner of the Royal Naval Flying Corps [sic] had been killed. The young Ottawa officer was reported missing then and since that time, until recently, nothing official has been heard of him. A short time ago the admiralty reported him dead.

Lieut. Cuzner was a graduate of Toronto University, and in September, 1916, he went overseas with the Royal Navy Flying Corps. While nothing official came to throw light upon the accident, a friend wrote that Lieut. Cuzner got separated from his squadron and was seen to drop “nose down’ [Note that this contradicts other reports that his fate was unknown]. Another report was to the effect that his commandant [Arnold?] saw the officer drop into a fog bank.

Lieut. Cuzner is survived by his mother Mrs. John Cuzner who is at present wintering in California. His two sisters Misses Eileen and May reside at 256 First Avenue.

There was plenty of misinformation in the newspapers during the First World War. The second headline of this story in the Ottawa Citizen stated that Eddy was at the front for 18 months prior to his disappearance, but in fact Eddy had arrived in the UK just seven months earlier and had only been at the front for a little more than a month before his death.

Eddy was one of 159 graduates of Ottawa Collegiate Institute who gave their lives in the First World War. After Eddy’s death, his mother Sarah travelled to Pasadena, California with Eileen and May to spend the winter of 1917-18 with extended elements of the Cuzner family and returned to Ottawa in May 1918. She would return to California for the winter of 1918-19 and died in the home of her remaining son, Willard, on Aylmer Avenue in Ottawa South (now Old Ottawa South) in 1923 at the age of 62. A piece in the Ottawa Citizen following her death implied her death was connected to Eddy’s:

Mrs. Cuzner was really a victim of the world war, being ill since her son Lieut. [sic] Edward Cuzner of the Royal Naval Air Service, was killed in action in 1916 [sic]. Her illness was a long one, and seldom in the experience of her friends has been witnessed more heroic patience, courage and cheerfulness under terrible suffering.

In the years following the death of Eddy until her death in 1923, his mother Sarah travelled by train to Southern California, there to spend a warm winter in the embrace of extended Cuzner family. James Cuzner, Eddy’s cousin (son of his Uncle Luke), had left Ottawa for California in 1869, travelling by ship around Cape Horn, had made a fortune in the lumbering business in California and resided in this Spanish-style mansion in Pasadena. Perhaps the warmth of California and family helped assuage the sorrow of the loss of three sons. Image from GoogleMaps

Today, the memory of young Eddy Cuzner is kept alive and cherished by his great grandniece, Alicia Hannah Cuzner, an Ottawa high school teacher. Alicia has worked hard to keep his memory alive on social media, on ancestry.com and contributing stories to the Historical Society of Ottawa and to the Canadian Virtual War Memorial. Eddy’s brother Willard, who ran the family business until his death in 1957, had two sons — Roy (Alicia’s grandfather) and Garry, a member of the Royal Rifles of Canada. Sergeant John Garry Cuzner, who was Eddy’s nephew, was four years old when Eddy was killed and was himself killed in action in the defence of Hong Kong in December of 1941.

One extraordinary and utterly unique heirloom that has been passed down to her through the generations is a ring that had belonged to Eddy and likely was returned to the family along with his personal effects or perhaps mailed home by him. The ring is made from aluminum from the wreck of German Zeppelin L-31 which was shot down near Potter’s Bar, a small town in Herefordshire, just north of London.

In the early hours of October 1st, 1916, Lieutenant Wulstan Tempest, a Canadian, shot down L-31, a German Zeppelin out to bomb London. It was captained by Heinrich Mathy with his crew of 18. All were killed when the flaming zeppelin fell into an ancient oak tree on the Oakmere Estate The deadly raids over England declined after this. The 19 German sailors were buried in the local cemetery. The spectacle of the 520-foot Zeppelin caught so dramatically in the searchlight beams had attracted tens of thousands of people over a wide area. Because of the height involved, the people were able to see it from many miles away. The next morning thousands more visited the site of the crash and many took souvenirs (like nuggets of molten aluminum) over the following weeks as it was studied then hauled away. Eddy had just arrived in London the day before the event and might even have witnessed the event on the northern horizon from the rail of SS Corinthian tied up at the Tilbury Docks on the Thames. It was certainly the talk of London for several days and it’s likely he went to the crash site along with the thousands of others.

British soldiers stand guard around the burned wreck of L-31 at Potters Bar. All that remained of the once the fire was out was her aluminum framework.

A cherished family heirloom — a ring, made from aluminum salvaged from the wreckage of the German Zeppelin L-31 which was shot down on the day Eddy arrived in London. Photos via Alicia Cuzner

Say His Name

One hundred and eight years ago in May of 1917, a jewellery store engraver in Berlin, wearing an eyepiece, held a small silver cup in his left hand. In his right palm he cupped the oak knob of his hand piece and with steady fingers began the cutting of the numeral 52 into the soft metal. Tiny silver shavings curled under the magnification of his loupe, bright incisions appeared that would soon darken with age and handling. The engraver was proud to be the one who was trusted to engrave the cups of Rittmeister Manfred Albrecht von Richthofen, who was then the toast of the city and indeed the Empire. It was his fourth cup for the Rittmeister that day. Did he give a second thought to the man who the numeral 52 represented? Likely not.

In a twist of fate, it would be another pursuit pilot from the Ottawa Valley who would participate in the shooting down and death of Richthofen a year later. Arthur Roy Brown, DSC & Bar was a Canadian flying ace of the First World War, credited with ten aerial victories. The Royal Air Force officially credited Brown with shooting down Richthofen although historians, doctors, and ballistics experts consider it all but certain that Richthofen was killed by an Australian machine gunner firing from the ground where he was shot by gunner Sgt Cedric Popkin. Regardless, it was Brown who he was duelling with and who fought Richthofen to the ground and in reach of Popkin’s gun.

Today, I can walk five blocks from my home in The Glebe to visit St. Matthews Anglican Church where the Cuzners once worshipped. It stands just 200 feet from 256 First Avenue where, in 1917, members of the Cuzner family received the news that Eddy had gone missing. At the back of the nave is a bronze plaque commemorating the 16 men of the parish who gave their lives in the First World War. There in the scented solitude of the narthex is the one remaining physical memory of a promising life cut short by duty. His name. ALBERT EDWARD CUZNER.