AN UNIMAGINABLE TASK

As I make my way onto the sprawling Royal Air Force (RAF) base in Yorkshire known as Leeming, the sound of a Rolls-Royce – Turbomeca Adour Mk.951 turbofan, generating 6500 lbs of thrust splits the air. A dual-seat Hawk of 100 Squadron leaps from the ground.

What strikes me most is that, even though so much has changed over the years, so much has stayed the same. The RAF Leeming base layout, buildings and hangars, in which Canadian crew members and ground staff served, are still here. In fact, they are a dominate feature of the base and are a key part of its vibrant fabric. The same is true at other bases across the United Kingdom. RAF Linton-on-Ouse is likely the best preserved Bomber Command base in the UK, with war damage still evident on some buildings.

So why am I at RAF Leeming? Well, the story really starts in this area of England many decades ago. No. 6 Group of Bomber Command, RAF, was comprised entirely of Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) squadrons. From 1942 to 1946, fifteen RCAF squadrons served in 6 Group. This concentration of Canadians, with a seasoning of other nationalities, operated primarily from Yorkshire at four major bases plus seven stations, namely Middleton St. George (County Durham), Topcliffe, Leeming, and Linton-on-Ouse. The squadrons mostly operated twin-engine Vickers Wellington as well as Handley Page Halifax and Lancaster four-engine bombers.

Somewhat surprisingly, given that almost 70 years have passed, three of these bases remain operational with the RAF, except for Middleton St. George which is now in civilian hands as the Durham Tees Valley Airport. Coincidentally this former 6 Group air base was owned by Vancouver Airport Services (an international airport operations subsidiary of the Vancouver International Airport) for a few years and sold off in 2012. All of the bases still retain their Second World War period air traffic control towers.

On a cold and blustery day at Durham Tees Valley Airport, the Air Traffic Control Tower looks much the same as when it was operating as the tower for RAF Middleton St. George in the Second World War. © Malcolm Tebbit

The Air Traffic Control Tower, RAF Linton-on-Ouse may have a newly installed staircase, but it is much the same as it was during the Second World War. Today Linton-on-Ouse is an active air base, home of the RAF's Central Flying School. © Frank Glover

Air Traffic Control Tower, at RAF Topcliffe, another 6 Group air base of the Second World War. Today it is a relief landing field for the RAF's Central Flying School at RAF Linton-on-Ouse. © Frank Glover

Related Stories

Click on image

The Air Traffic Control Tower at RAF Leeming, now a training airfield for the Royal Air Force. © RAF Leeming, Ministry of Defence, UK

Because of the RAF–RCAF connection at these former Bomber Command bases, there was a deep-felt desire on both sides of the “pond” to remember and honour those fellows who had come before. As a result, there are a variety of individual memorials and plaques scattered across the north of Britain, but there was no national commemorative site in the UK for Canadians who served in Commonwealth Air Forces as a whole – that is, until RAF Flight Lieutenant Alfie Hall came to that realization in May 2010 and decided to do something about it.

A year later, with a great deal of support on both sides of the ocean, a new site was dedicated as the Royal Canadian Air Force Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, UK. You can find out more at www.rcafmonument.ca

Key players in the Canadian Memorial project pose after the dedication ceremony. (L-R): Major Jason Furlong RCAF, SAC Dave Turnbull, and Flight Lieutenant Alfie Hall of the RAF © Mrs. Hall

Each of the provinces is named at the Royal Canadian Air Force Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, UK. The idea was turned into reality by personnel and leadership from two current RAF (former RCAF) bases – RAF Leeming and RAF Linton-on-Ouse and in partnership with the RCAF and many sponsors. © Ministry of Defence, UK

The dedication ceremony of the Memorial, 8 July 2011, with media, veterans, families and VIPs in attendance. © Ministry of Defence, UK

Two commemorative works of art were also commissioned in support of the Canadian Memorial. The first is a painting of a 405 Squadron RCAF Halifax with accompanying prints by artist John Stevens and the other a full-sized bronze sculpture of a Canadian airman accompanied by miniature replicas by Sara Ingleby-MacKenzie.

Granite and marble from Lafarge Canada was donated to the Memorial and flown over to the UK by the RCAF, along with a 426 Thunderbird Squadron propeller blade recovered in Belgium from the crashed Handley Page Halifax, LW682 (another prop from the same Halifax is on display at CFB Trenton).

Ingots of aluminium from this recovered Halifax aircraft were also provided by the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta and used to make the ceiling of the recently inaugurated Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park, London. The stone for the new Canadian Memorial was then installed by stonemason Mr. Nick Johnson, who demonstrated his superb craftsmanship and provided ongoing technical support, undertook liaison with the National Memorial Arboretum and worked virtually for free to make this project a reality.

I became aware of the Canadian Memorial project in a unique way. Working with the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs in London, I became the temporary “custodian” of a strange J-shaped crate (aka “the prop”) left on the tarmac of Luton airport, which had been off-loaded from the Canadian Prime Minister’s CC-150 Polaris (Airbus A310) when he came for the Queen Elizabeth Jubilee celebrations in 2012. The Memorial trustees are hoping to incorporate both the full-sized sculpture and the bent prop into the Memorial as Phase II of the project.

Commemorative painting, highlighting 405 Squadron aircraft and the Memorial by talented artist John Stevens, MBE. © John Stevens

“Counting them home” The full-sized version of this bronze miniature is destined to be part of the Royal Canadian Air Force Memorial at some point in the future. Artist Sara Ingleby-MacKenzie of Somerset, England took her inspiration for this statue from Ian W. Bazalgette, a Canadian RAF pilot and Victoria Cross recipient. © Ministry of Defence, UK

The Memorial was inspired heavily via the No. 6 Group of Bomber Command connection, although it is in fact dedicated to all Canadians who served in Commonwealth Air Forces. With that in mind, I combed the National Archives of Canada and the Imperial War Museum to come up with a series of photographs of the men and the machines of No. 6 Group, to whom we owe a great deal.

There are a few stories of some of those men whom I also wanted to mention in particular, with the help of the veterans and their families and friends. The selected photographs speak to the danger, fatigue, friendship and the unimaginable tasks which our country asked them to perform day after day.

The Machines of No. 6 Group, Bomber Command

Halifax Mark II Series I, with serial number W7676 TL-P, of No. 35 Squadron RAF Linton-on-Ouse, Yorkshire piloted by then Flight Lieutenant Reginald Lane (later Lieutenant-General, RCAF). The early Series Halifaxes differed from those operated by the RCAF in that they had V-12 Merlin liquid-cooled engines. Later models employed the Bristol Hercules XVI radial engines. © IWM (COL 185)

Air and Ground crew members of a No. 428 “Ghost” Squadron RCAF (calling themselves Hitler's Haunters), Avro Lancaster (KB760, NA-P, P for Peter), pose with a load of ordnance bound for Bremen, Germany on the occasion of the squadron's 2000th sortie. © National Archives of Canada

Looking more like Canada than Great Britain, RAF Balderton in Nottinghamshire is covered in a wintry blanket of snow on 20 January 1942 as aircrew return from a flight in a Hampden of No. 408 (Goose) Squadron, RCAF. During the war, the Goose Squadron changed from the Hampden Aircraft to Halifax, to Lancaster, to Halifax, and back to Lancaster aircraft. It flew an amazing 4,610 sorties and dropped 11,340 tons of bombs. A total of 170 aircraft were lost and 933 personnel were killed, listed as missing in action (MIA) or prisoners of war (POW). Squadron members won two hundred decorations, and 11 battle honours for its wartime operations. © IWM (CH 4742)

Halifax B Mark II, (W7710 LQ-R) Ruhr Valley Express, of No. 405 Squadron, RAF Pocklington, Yorkshire. This 405 Squadron “Hallie” crashed at Liehuus, Denmark, on the night of 1 Oct 1942. As its motto, DUCIMUS – We Lead – indicates, 405 Squadron was a leader since its formation as the first RCAF Bomber Squadron in England on 3 April 1941. From its first operation on 12 June 1941 until the end of the war in Europe, 405 was actively employed in offensive operations over land and sea, participating in most of Bomber Command's heaviest and most telling assaults on targets in Germany, the occupied countries and Northern Italy. During its wartime service, 405 was attached to RAF Coastal Command for a brief period and carried out numerous anti-submarine patrols similar to the squadron's present role. Shortly after the duty with Coastal Command, 405 became part of 6 Group and later moved to the elite Bomber Command in 8 Group as a Pathfinder Squadron. © IWM (CH 6614)

Able Mabel, a 100 Squadron RAF Lancaster, flown at times by an RCAF commander. The squadron was based at RAF Waltham. © IWM (CH 14986)

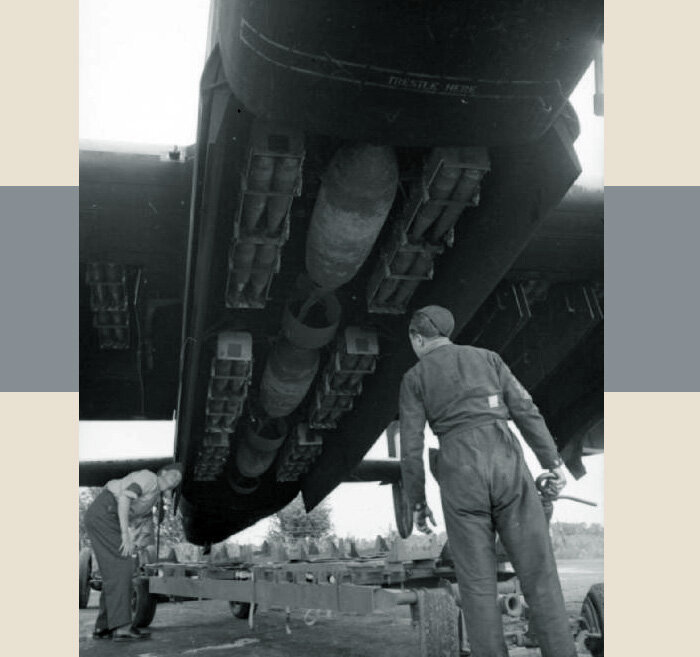

Ground crew bombing up a Handley Page Halifax Mark II, “LQ-Q” of No. 405 Squadron RCAF, at RAF Pocklington, Yorkshire. Ground crews worked tirelessly and around the clock to ensure that the aircraft in their care were serviceable and armed. © IWM (CH 6609)

The Avro Lancaster is to Bomber Command what the Supermarine Spitfire was to Fighter Command – an icon.

The Handley page Halifax Mk III in flight, showing its late model rectangular tail fins. Although the Avro Lancaster took the lion's share of fame in Bomber Command, the Halifax played a massive and vital role – especially in the RCAF. More RCAF aircrew served on Halifaxes than on Lancasters. The Halifax was utilized in a variety of roles including glider towing, maritime patrol and casualty evacuation.

The Men

One of the many crews based out of Leeming was the RCAF's 429 “Bison” Squadron crew of Halifax LK802. Family member Jeff Austin recalls the bravery of that crew who, when flying their Halifax III AL-F back to RAF Leeming from a raid on Dusseldorf, 23 April 1944, were attacked by a German fighter. (http://eastleedsmag.net/020/20_austinplein.html and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zvLSPNukEh4) The aircraft had suffered badly, was on fire and was not going to make it back to England. Engineer, Sergeant Herbert Austin and Pilot, Flying Officer Francis Fennessey were preparing to bail out but didn’t make it. The five other crew members did manage to exit the burning aircraft. Gunner, Sergeant Percy Crosswell (later shot and killed after escaping as a POW), Wireless Operator, M/Sgt Arthur Kempton, Bomber/Aimer, Flying Officer Bruce Low and Gunner, Sergeant Jim Miller were taken prisoner and the Navigator, Pilot Officer Alex Achtymichuk was lost at sea. Eye witness accounts describe the aircraft heading for the village of Herkingen before suddenly being manoeuvred away to crash in the St. Elizabeth polder. The local Dutch residents honoured the crew and Sergeant Austin with a memorial just after the war and, in 1981, invited the Canadian/UK family of Herbert Austin to Holland for the naming of a square in a housing estate at the site of the crash, “Austinplein”. In 2012, there were fresh commemorative ceremonies in Holland, organized by the ever-remembering Dutch, for the entire crew of LK802.

Sergeant Herbert I. Austin's formal RCAF crew photograph from 1943. Every winged airman coming out of British Commonwealth Air Training Plan bases went to a photo studio to have an official portrait taken, at his own expense, to be given to parents, family and sweethearts. © Family of Herbert Austin – reproduced with permission

The international crew of RCAF Halifax LK802 in the winter of 1943–44. (L to R): Low (Canada), Achtymichuk (Canada), Crosswell (Canada), Kempton (USA), Miller (Canada), Austin (United Kingdom), Fennessey (Canada) © Family of Herbert Austin – reproduced with permission

Another story from RCAF Leeming concerns 429 Squadron alumni and Flight Engineer Doug Petty who still lives in Yorkshire (as this article is written, his wife Betty has just passed away and we send him our condolences and thoughts). As a Brit, he was assigned to the RCAF and was a Halifax/Lancaster crew member with Canadian Robert Kealey Mitchell. Their story speaks to the bonds of friendship which continued after the war and family connections which are still around today.

In the words of the Mitchell family (Steve and Elizabeth), reinforced by Doug’s memories and stories, they recount the following,

“Robert Kealey Mitchell won a Distinguished Flying Cross for laying mines at the mouth of a Norwegian fiord in December 1944. The mines exploded the next day when a German troop-carrier hiding in the fiord emerged, taking all aboard permanently out of action. Doug Petty was beside him.”

“It was Doug, not Robert, who talked about how terrifying that night was for their crew of seven. How thick the fog was. How brave Norwegians, hearing the engines approach, lit their homes to guide the way, in breach of the strict blackout laws. How the fiord was so deep that, nearing the target, their Halifax bomber flew below the heights of the cliff walls and the German artillery shot down on them. How Robert flew that plane in such erratic, unpredictable patterns that the radio broke loose from its moorings. How their plane was the only one of seven to accomplish the mission and return safely.”

With the dangers also came teamwork and everlasting friendship. According to Doug, as written by the Mitchell family,

“Flying in 1943–44 could be tricky. The Halifaxes had either Rolls-Royce in-line engines or Bristol radial engines. The Bristol engines had a nasty tendency to form ice on the carburettors on the descent back to base. On one such return, two engines froze over the Channel. Robert had to fly so low to re-start them that Doug fired off flares in the colours of the day, making sure the English coastal defenders could identify their plane as friendly.”

“Doug talked about the fun times too. As a team, he and Robert were frequently assigned to take out-of-service aircraft to out-of-the-way fields. They loved these assignments! Coming back to base was always an adventure, hitch-hiking, taking trains, or using aviation fuel, in petrol-short England, to gas up a used motorcycle Robert had purchased for the purpose. It blew its engine only occasionally with the too rich fuel. Happily, they could pop in on Doug’s parents in the English countryside, a couple who hosted many weekend retreats for the war-weary Canadians who flew with their son.”

Crew of F/O Robert Mitchell and Engineer Doug Petty's Halifax with 429 Squadron. Back Row (L to R): William Manion, Fred Bullen, Robert K. Mitchell, Second Pilot (this flight only), Douglas Petty. Front Row (L to R): William Hay, Ground Crew, E. Tamella, Ground Crew, Len Jodrell. © Family of F/O Robert Mitchell – reproduced with permission

Air and Ground Crew 419 Squadron. No. 419 Squadron was formed at Mildenhall, Suffolk, on 15 December 1941, as the third RCAF bomber squadron overseas. The first CO was Wing Commander John “Moose” Fulton, DSO, DFC, AFC, a native of Kamloops, British Columbia, and it was from him that the unit gained its nickname. Originally in No. 3 Group of Bomber Command, the squadron joined No. 6 (RCAF) Group upon the latter's formation on 1 January 1943. From Mildenhall it moved to Leeming, Topcliffe and Croft for short periods before settling down, in November 1942, at Middleton St. George, where it remained based until the end of the European war. Beginning operations with Wellington medium bombers, No. 419 later converted to Halifax heavy bombers and then to Lancaster Xs. Over a span of roughly three-and-a-quarter years it logged 400 operational missions (342 bombing missions, 53 mining excursions, 3 leaflet raids and 1 “spoof”) involving 4,325 sorties. One hundred and twenty nine aircraft were lost on these operations. Part of a series of photos taken by war photographer Henry Prince. Air and ground crew “D” Dog's diggings, from left: F/O R.V. Daly, LAC Jerry Greves, AC Frank Beaves, LAC Vic Hewitt, Sgt. N.C. Fraser, Corp. Don Mersereau, F/L A.J. Byford, Sgt. D. Logan, AC Ken Barter. © National Archives of Canada

The “D” Dog crew from the previous “Gladys Hotel” photograph was led by Flying Officer Byford. “D” Dog was Lancaster KB-738, VR-D, of 419 (Moose) Squadron. We were sent this image by reader John Dicker showing the Byford crew with D-Dog in England. Dicker comments: “Dad’s best friend and close friend of our family in North Bay, F/O Russ K. Nickle, was the Nav on this particular aircraft when he was KIA along with the rest of the crew on 28 December 1944, on their 19th Op (Opladen, Germany). The photograph, which I received many years ago from Vince Elmer, the 419 Squadron historian, shows F/L Byford and his crew in front of KB-738, VR-D, prior to 28 December 1944. You can just see the “D” to the left of the pic. I find it awesome to this day to look at that pic and to think that it was the very aircraft in which Russ was lost that fateful night. Russ’ captain was Flying Officer How and the lost men were a completely different crew than Byford’s.”`

Aircrew from 427 “Lion” Squadron, RCAF at the London Zoo adopting “Mareth”, a cub of “Rota”, Winston Churchill’s pet lion. As well, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer adopted the squadron on 24 May 1943 and allowed the names of their stars (such as Lana Turner, Greer Garson, Joan Crawford and Hedy Lamarr) to be displayed on squadron aircraft. In addition, MGM presented a bronze lion to the squadron, and from this came the name “Lion Squadron”. © Archive of ZSL, London

A very tired young Halifax pilot of No. 405 (Vancouver) Squadron RCAF, after returning from Germany July/August 1942. The physical and mental toll on RCAF aircrew is clearly evident in this photograph. © IWM (CH 6627)

RAF Pocklington, Lancaster B.X with the entire squadron, ground and aircrew of 419 (Moose) Squadron. © National Archives of Canada

Officers of No. 405 Squadron RCAF, outside their mess at Topcliffe, Yorkshire. Note that the photo includes at least five female WRAF officers (Women's Royal Air Force). © IWM (CH 4718)

One of Canada's finest aviation artists, Peter Mossman, wrote to us with this photo of his brother James with his 429 Squadron Halifax crew, sent to him back home in Canada when he was just 7 years old. James is the man hunkered down in the middle. Imagine the thrill a 7-year-old boy would have to find this picture of his hero brother in the mail. From left to right we have: F/O Willis O'Connor (mid-upper gunner), P/O D. Hartley (flight engineer RAF), F/O Guy Wheeler (tail gunner), F/O James D. Mossman (bomb aimer), F/O Don G. Gillis (pilot), P/O J.M. Haynes (wireless air gunner), F/O Gerry B. Ullett (navigator). Peter Mossman writes: “I know Gillis and Ullett got the DFC, Willis married Billy Bishop's daughter, Wheeler was a Squadron Leader, but dropped in rank to go on ops and the pilot and W/O had done a tour together on Coastal Command before joining 429 – my brother had already crewed up when approached by Ullett, another Toronto boy, to join him and his crew, which Jim did and his previous crew were lost on their first trip and Jim is eternally grateful to Gerry and they stayed in touch until Ullett passed away not too long ago.” This crew finished 32 ops together, except for Wheeler, who was not on the 32nd op.

Wing Commander D.C. Hagerman aboard Lancaster B.X KB707 (VR-W) of 419 (Moose) Squadron, RCAF at RAF Middleton St. George. The youth of the leadership of the RCAF can be seen on the face of this Wing Commander. © National Archives of Canada

Ready for action... a rather hazardous photo in front of a spinning prop of a Vickers Wellington with RCAF Pilot J. Mason and his 420 Squadron crew. Though 420 “City of London” Squadron (sometimes called Snowy Owl Squadron) ended their combat service on Halifax and Lancaster bombers, they first flew medium bombers like this Wellington, as well as Handley Page Hampdens and the much maligned predecessor of the Lancaster – the twin-engined Avro Manchester. The “Wimpy” (nickname of the Wellington) in this shot indicates that it was taken before October 1943, when they ceased Wellington operations. © National Archives of Canada

Bomb Aimer, Sergeant Stuart N. Sloan (UK), MVO, DFC, CGM (left) of 431 (Iroquois) Squadron, RCAF, took control of a damaged RCAF Wellington over enemy territory and landed it at RAF Cranwell. Amazing! They then decided to make him a pilot (no kidding) and eventually commissioned him a Wing Commander, RAF.

“One night in May 1943, Flying Officer Bailey and Sergeants Sloan and Parslow were members of the crew of an aircraft detailed to attack Dortmund. Shortly after its bombs had been released, the aircraft was badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire whilst held by the searchlights. Evasive action was taken by putting the aircraft into a steep dive but this proved ineffective and the bomber was subjected to heavy fire whilst still illuminated. The situation became critical but Sergeant Sloan, displaying superb skill and determination eventually flew clear of the defences and headed for this country. A hatch was open and could not be closed, the rear turret door was also open and wind of great force blew through the length of the aircraft. All the lights in the navigator's cabin were extinguished but in the face of extreme difficulty, Sergeant Parslow plotted a course. On the return flight, he and Flying Officer Bailey assisted Sergeant Sloan in every way within their power and eventually this gallant airman flew the badly damaged bomber to an airfield and effected a good landing. In appalling circumstances these members of aircraft crew displayed courage, determination and fortitude of the highest order.” Extract from the London Gazette

The incident is still remembered as a magnificent feat for a seasoned pilot, let alone a bomb aimer with a very tentative knowledge of the pilot's trade. Sgt Sloan was given an immediate Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, which ranks just below the VC as the highest award open to NCOs. He was also commissioned in the field and sent on a pilot's course and, in 1945, completed a successful tour with the famed 158 Squadron at Lissett (flying Halifax MkIII). He ended the war as a Flight Lieutenant with a DFC and relinquished his commission as a Wing Commander in 1975. Postwar he served with the King's Flight. He joined Vickers Armstrong as a test pilot in 1951, flying various types and displaying at the 1953 Farnborough airshow.” © IWM (CH 10320)

I thought it important to also mention that two Canadian winners of the Victoria Cross were Bomber Command alumni, one serving in the RAF and the other in the RCAF. The notices from the London Gazette are self explanatory.

Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, VC, DFC (19 October 1918 – 4 August 1944) was born in Calgary, Alberta and while serving in the Royal Air Force was awarded the Victoria Cross. © IWM (CH 15911)

Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, VC, DFC – 635 Squadron RAF

Extract from the London Gazette, 7 August 1945:

Ed. note: with factual errors corrected via Dave Birrell's book, “Baz, The Biography of S/L Ian Bazalgette, VC”

Acting Squadron Leader Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, DFC, RAFVR

On 4 August 1944, Squadron Leader Bazalgette was part of a Pathfinder squadron detailed to mark an important target at Trossy-St. Maximin for the main bomber force. When nearing the target his Lancaster came under heavy anti-aircraft fire. Both starboard engines were put out of action and there was a serious fire in the starboard main-plane. The bomb aimer was badly wounded.

As the “master bomber” and deputy “master bomber” had already been shot down, the success of the attack depended on Squadron Leader Bazalgette, and this he knew. Despite the appalling conditions in his aircraft he pressed on gallantly to the target, marking and bombing it accurately. That the attack was successful was due to his magnificent effort.

After the bombs had been dropped the Lancaster dived, practically out of control. By expert airmanship and great exertion Squadron Leader Bazalgette regained control. But the port inner engine then failed and the whole of the starboard main-plane became a mass of flames.

Squadron Leader Bazalgette fought bravely to bring his aircraft and crew to safety. The mid-upper gunner was overcome by fumes. Squadron Leader Bazalgette then ordered those of his crew who were able to leave by parachute to do so. He remained at the controls and attempted the almost hopeless task of landing the crippled and blazing aircraft in a last effort to save the wounded bomb aimer and helpless gunner. With superb skill, and taking great care to avoid a small French village nearby, he brought the aircraft down safely. Unfortunately, it then exploded and this gallant officer and his two comrades perished.

His heroic sacrifice marked the climax of a long career of operations against the enemy. He always chose the more dangerous and exacting roles. His courage and devotion to duty were beyond praise.

Left: Andrew Charles (Andy) Mynarski, VC (14 October 1916 – 13 June 1944) © IWM (CHP 975) Right: Statue of Pilot Officer Mynarski, sculpted by Keith Maddison, fundraising by the Northern Echo / Forgotten Hero Appeal / Wartime Memories Project, inspired by Betty Amlin, was dedicated in 2005 at RAF Middleton St. George. © Copyright Nick W, Creative Commons license

Andrew Charles Mynarski, VC – 419 Squadron RCAF

Extract from the London Gazette, 11 October 1946:

Pilot Officer Andrew Charles Mynarski (Can/J.87544) (Deceased), Royal Canadian Air Force, No. 419 Squadron (RCAF)

Pilot Officer Mynarski was the mid-upper gunner of a Lancaster aircraft, detailed to attack a target at Cambrai in France, on the night of 12 June 1944. The aircraft was attacked from below and astern by an enemy fighter and ultimately came down in flames.

As an immediate result of the attack, both port engines failed. Fire broke out between the mid-upper turret and the rear turret, as well as in the port wing. The flames soon became fierce and the captain ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft.

Pilot Officer Mynarski left his turret and went towards the escape hatch. He then saw that the rear gunner was still in his turret and apparently unable to leave it. The turret was, in fact, immovable since the hydraulic gear had been put out of action when the port engines failed, and the manual gear had been broken by the gunner in his attempt to escape.

Without hesitation, Pilot Officer Mynarski made his way through the flames in an endeavour to reach the rear turret and release the gunner. Whilst so doing, his parachute and his clothing, up to the waist, were set on fire. All his efforts to move the turret and free the gunner were in vain. Eventually the rear gunner clearly indicated to him that there was nothing more he could do and that he should try to save his own life. Pilot Officer Mynarski reluctantly went back through the flames to the escape hatch. There, as a last gesture to the trapped gunner, he turned towards him, stood to attention in his flaming clothing and saluted, before he jumped out of the aircraft. Pilot Officer Mynarski’s descent was seen by French people on the ground. Both his parachute and clothing were on fire. He was found eventually by the French, but was so severely burnt that he died from his injuries.

The rear gunner had a miraculous escape when the aircraft crashed. He subsequently testified that, had Pilot Officer Mynarski not attempted to save his comrade’s life, he could have left the aircraft in safety and would, doubtless, have escaped death.

Pilot Officer Mynarski must have been fully aware that in trying to free the rear gunner he was almost certain to lose his own life. Despite this, with outstanding courage and complete disregard for his own safety, he went to the rescue. Willingly accepting the danger, Pilot Officer Mynarski lost his life by a most conspicuous act of heroism which called for valour of the highest order.

Sometimes, the enemy was the weather. One that could kill as easily as a German fighter, and one you could not escape. Flight Officer Humphrey Watt’s crew (above) of 426 Squadron, flying Halifax NP793 set off from RCAF Linton-on-Ouse on 5 March 1945 to attack Chemnitz. They crashed shortly after take-off due to severe icing, killing all of them. That night, 11 Linton and Tholthorpe based RCAF aircraft were lost – 5 due to severe icing. The Yorkshire Aircraft website states: “This night was a bad night for Bomber Command, a number of aircraft were to be lost due to suffering from severe icing conditions soon after taking off from their Yorkshire bases, these icing conditions effected the control surfaces of the aircraft and there were a number of accidents, it was one of seven Halifaxes to crash due to identical circumstances. Halifax NP793 was one of 760 aircraft leaving to bomb Chemnitz on 5 March 1945 on Operation Thunderclap, the crew left their Linton-on-Ouse base at 16.48hrs and flew in a north-easterly direction over the Moors and climbed. Crews were ordered to circle base until all the unit's aircraft were in the air so they could all continue as one large bombing force, where the pilots of each aircraft flew during this waiting time was more or less up to them so long as they were over Linton at a set time, in this case around 17.30hrs. No adverse weather was forecast prior to taking off, though this would prove to be an inaccurate forecast. Soon after taking off this aircraft began to encounter the icing conditions, the pilot began circling in an attempt to get above freezing fog which was present over much of North Yorkshire on this evening but this attempt failed and the aircraft came down after control had been lost at a location to the south of Hutton-le-Hole and near Westfield Farm at 16.59hrs. Some of the crew, possibly three, are believed to have survived the initial crash and are thought to have been trying to attempt to rescue other members of the crew when the bomb load exploded, this resulted in all seven on board the aircraft being killed.” Though the photo's history will not allow us to say who is who, but headstones at Harrogate Stonefall Cemetery, Yorkshire let us know who the individuals were: H.S. Watts, Pilot, F. MacG. Myers, Navigator, W.A. Way, Bomb Aimer, M.W. Coones, Air Gunner, R.A. Biggerstaff, Air Gunner and B.J. McCarthy, Wireless Operator. © Memorial Room RAF Linton-on-Ouse

The “Ops”

Operations for Doug Petty, Robert Mitchell and crew looked to average 6 hours night flying time – Germany and back.

One page of many, in the logbook of Engineer Doug Petty, 429 Squadron. The notes show a myriad of typical German industrial targets and the totals at the bottom tell us much about the RCAF and Bomber Command night bombing role – with 31 hours in night bombing ops and 6 hours 35 minutes in daylight raids. © Doug Petty – reproduced with permission

Three 1,000-lb MC bombs, small bomb containers (SBCs) filled with 30-lb incendiary bombs in the belly of a Halifax Mark II of No. 405 Squadron, RAF Pocklington, Yorkshire. You can also note that the Halifax also carries some of this ordnance in its smaller wing bays or “cells”. Germany will reap the whirlwind tonight. © IWM (CH 17362)

Preparing to board Lancaster B.II 432 (Leaside) Squadron. It was first formed at RAF Skipton-on-Swale in May 1943, as part of No. 6 Group of RAF Bomber Command. The unit was equipped with Wellington X bombers. The squadron deployed to RAF East Moor in mid-September, equipping with Lancaster IIs in October. In February 1944 they changed to Halifax IIIs, upgrading these to Halifax VIIs in July. As part of a Royal Canadian Air Force public relations plan, the town of Leaside officially “adopted” No. 432 Squadron RCAF. Formed and adopted on 1 May 1943, the squadron took the town's name as its nickname, becoming 432 “Leaside” Squadron RCAF. The sponsorship lasted the duration of the war. The squadron was disbanded at East Moor in May 1945. © National Archives of Canada

From the massive Grand Slam and Tallboy bombs designed for hitting submarine pens and other hard-to-knock-out targets to the 4 pound general purpose bomb over this armourer's shoulder to the diminutive and terrifying 4 pound incendiary, Bomber Command delivered body blows to the Third Reich, night after night, for five years. © National Archives of Canada

Aircrew of No. 405 (Vancouver) Squadron RCAF board their Wellington Mk II. 405 Squadron flew the very first operational sortie by an RCAF unit during the war – 12–13 June, attacking the railway marshalling yards at Schwerte – only ten weeks after being formed at RAF Driffield, Yorkshire. 405 remains today a long-range bomber squadron, flying the CP-140 Aurora on anti-submarine patrols on the East Coast of Canada. © IWM (HU 108387)

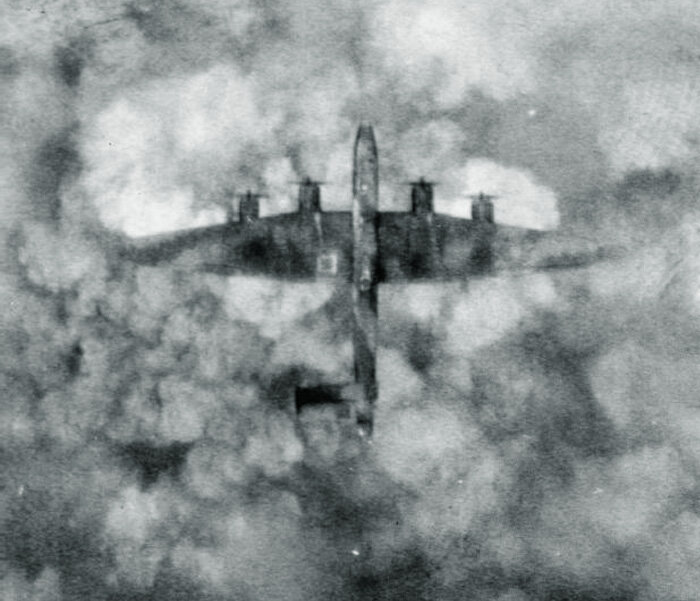

A Handley Page Halifax of No. 6 Group flies over the smoke-obscured target during a daylight raid on the oil refinery at Wanne-Eickel in the Ruhr. 111 Halifaxes of 6 Group and 26 Avro Lancasters of No. 8 Group took part in the raid which destroyed a chemical factory but only inflicted minor damage on the refinery itself. © IWM (C 4713)

Trouble did not always come from below. Here we see Halifax B Mark III, LW127 HL-F, of No. 429 Squadron RCAF, over Mondeville, France just moments before her death. She has lost her starboard tailplane and rudder after it was knocked from the fuselage by bombs dropped by another 429 Halifax above it. LW127 was one of 942 aircraft of Bomber Command, one of the famous Thousand Plane Raids, despatched to bomb German-held positions, in support of the Second Army attack in the Normandy battle area (Operation GOODWOOD), on the morning of 18 July 1944. The crew managed to abandon the aircraft before it crashed in the target area. © IWM (CE 154)

Imagine the tension. Three Halifax crew before takeoff work as a team to execute the op. This is the interior of a Handley-Page Halifax B Mk II Series I of No. 35 Squadron RAF, looking forward to the flight engineer's seat, prior to takeoff from Linton-on-Ouse, Yorkshire. Below the engineer's position can be seen the navigator at his position closer to the camera with the front gunner alongside him. On the right hand side of the Halifax and Lancaster cockpits was a fold down seat that the flight engineer used. The centre mounted throttles could be reached by both the pilot and flight engineer; on takeoff the flight engineer handled these while the pilot concentrated on keeping the heavily laden aircraft straight. The flight engineer was there to assist the pilot, monitor the engines and fuel levels and transfer fuel to maintain the balance of the aircraft. © IWM (D 6028)

Handley Page Halifax aircraft of No. 427 Squadron RCAF during a major night raid by a mixed force of 128 aircraft on the German submarine base at Lorient, France. Note aircraft just above the largest group of incendiaries plus another possible aircraft silhouette to the right of the harbour mouth. Also note that the bomb hits and fires have mostly hit their mark. © IWM (C 3387)

The terrible beauty above Pforzheim, Germany at night – a powerful photoflash flare is ignited to allow night photography while target indicators (TIs) float down to the ground. © IWM (C 5012)

Halifax Bomber on a daylight raid. Note the difference between lines of bomb craters. Some, like the line at the lower right are perfectly straight, while others seem to fall in tight groupings and others seem like single hits. © National Archives of Canada

Many did not make it off the runway. Many did not make it home. Many made it home only to crash on landing. Here, a Merlin-powered Bomber Command Halifax burns at its home airfield. Photo: RAF Bomber Command Diary

Memories are preserved and new ones are being made by a special group of individuals who have made it part of their day-to-day mission to remember the past and inform future generations.

Leadership for the RCAF Memorial is provided by Flight Lieutenant Alfie Hall, whose enthusiasm is as boundless as it is obvious. He assures me that he is not a one-man team and is quick to mention Flight Lieutenant Dave Williams from RAF Linton-on-Ouse, SAC Dave Turnbull, RAF Leeming and Major Jason Furlong, RCAF as his co-conspirators.

He also takes pains to mention all of the sponsors, private and corporate, who made the Memorial happen. I learned during my visit that Alfie has been given a tremendous amount of support (time, encouragement and resources) in his commemorative activities by the senior leadership at RAF Leeming, namely Group Captain Tony Innes and the current master of RAF Leeming, Group Captain Steve Reeves, as well as Alfie’s direct boss, Sqn. Leader Jeff Metcalfe. They both provided me with a warm welcome. The same is true for Dave Williams who has been given support by Air Commodore Terry Jones and Group Captain David Cooper. All of these persons have demonstrated leadership and vision of the highest order.

As we think back over the last 70 years, we hope these photos and few words bring the experiences of the tens of thousands of flying and ground crew members, serving during the war, to a more personal level for you.

Reading about these experiences, and as an ever-learning pilot myself, I feel just the faint hints of the type of fear that must have been in every person who was called upon to serve and the courage it must have taken to overcome that fear.

Speaking as a Canadian, I want to thank all of our UK and Allied “cousins” for thinking of us, putting thoughts into action and keeping the memory of the sacrifices made for our freedom. The RCAF Memorial in the National Memorial Arboretum and all of the individual statues, plaques and memorials in the UK and in Europe are deeply appreciated. I am personally looking forward to the Memorial’s next phase.

Mark Fletcher