SPITBOMBER

Friends of 401 Squadron fighter pilot Bill McRae knew he had a deep and very passionate love affair with the beauty known as the Supermarine Spitfire. But like all lasting relationships, Bill understood that it was best to be realistic about their partner's flaws.

Most pilots who flew the Supermarine Spitfire will agree that it was a great aircraft, easy to fly and with no nasty surprises for even a ham-fisted driver. But when we began adding external gadgets for which it had not been designed, such as fuel tanks and bombs, problems began to emerge. New terms crept into our vocabulary, such as "aileron up-float" and "air locks". When dive-bombing began, maximum permissible airspeed was stressed, which I seem to recall was 457 mph. For brevity I will use Vne (Velocity Never to Exceed), although this term was not in vogue at the time.

Some of us had already used the external so-called "slipper tanks" of either 30 or 90 gallon capacity. While occasional problems were encountered with these tanks, they were minor compared with the troubles that lay ahead with the 45 gallon "cigar" tank when 401 Squadron converted to Mk IX Spitfires in October 1943. Unlike the slipper tank, which fitted snugly against the aircraft’s belly, the cigar tank was slung some distance below the belly, which some of us believed might be the cause of our problems. (Only recently I have learned that the fault was eventually traced to the carburetor.) The problem was failure of the engine to continue running when switching from main tanks to external or from external back to mains. The latter of course was more serious, since this would usually take place over enemy territory. In fact, almost one quarter of the pilots lost by 401 Squadron during my tour were lost due to this cause. None of the ORs (Operational Records) that I have come across make any mention of tank problems, referring to the incidents only as "engine failure" or "engine trouble". There was a third problem with this tank; frequently it would refuse to jettison, whether empty or full. My aircraft at the time, MH887, for some reason was a particular offender in this regard.

A typical cigar-style centreline auxiliary drop tank system for the Spitfire.

The Slipper Tank. A group of 127 Squadron RAF airmen swarm a Spitfire on a muddy forward airfield known as B.60 at Grimsbergen, Belgium in December of 1944. The Spit carried both a pair of 250 lb under-wing iron bombs and a “slipper” auxiliary gas tank between her gear legs. Photo from Andy Ingham Collection, the spitfiresite.com

The incidents of failure became so severe during the winter of 1943–44 that we began adding a thirteenth man as spare on squadron operations, as is indicated by the thirteen pilots listed in some ORs during this period for what would ordinarily have been a twelve man show. The early return aircraft can be identified by the earlier downtime, provided the clerk noted it correctly, but unfortunately in any OR I have seen, it is not noted whether the early return was the spare or someone replaced by him.

Soon after takeoff we would switch to the external tank. If someone had a failure he would turn back and his place would be taken by the spare. My log book records at least one occasion when I turned back for this reason, and another when I filled in as spare. I witnessed one scary incident when one of our pilots, Hubbard, had the bad luck to experience all three failures on the same flight. My section of four had just taken off from the grass of RAF Hawkinge (a field which ended at the edge of a cliff at the Channel edge,) and was circling for the others to join up, when he called to say his tank had failed. He was already out over the channel, so immediately began a turn back to Hawkinge, while switching back to main tanks. The engine still would not catch, and in preparation for a forced landing he attempted to jettison the tank. It refused to come off. He now had no choice but to stretch out the glide for a landing, downwind, with 45 gallons of fuel hanging under his seat. He reached the field, where I saw him hit and immediately erupt into a fireball. He survived, but seriously burned.

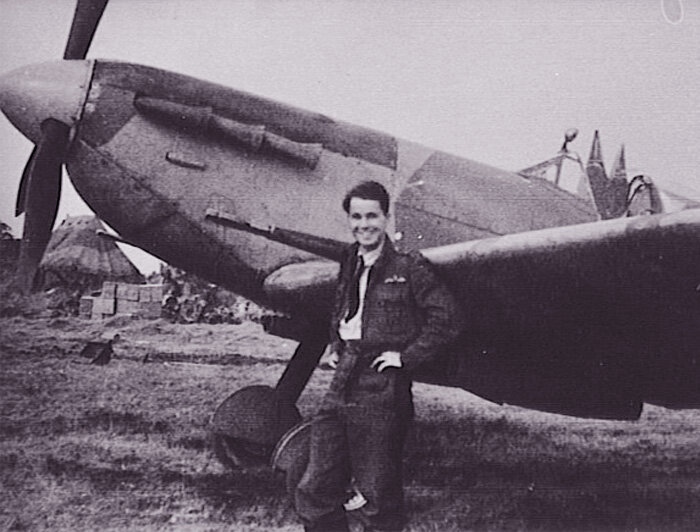

A wonderful photo of Bill and a clipped wing Spitfire Vb taken in England in the winter of 1943–44 – just prior to his dive-bombing course at RAF Fairwood Common. Photo via Marilynn Best (née McRae)

Related Stories

Click on image

In April of 1944, after a short dive-bombing course at Fairwood Common in Wales, where we used only small smoke bombs, 401 moved from RAF Biggin Hill to RAF Tangmere and began dive-bombing as part of our regular duties. The Spitfire had been used as a dive-bomber in the Mediterranean theatre, but there I believe only two wing-mounted 250 lb bombs were used. In Normandy 401 Squadron carried only the belly-mounted 500 pounder. The targets assigned to us, mainly V-1 launching sites and occasionally small railway bridges, required pinpoint accuracy, something almost impossible to achieve with the technique recommended for releasing belly-mounted bombs from a Spitfire, i.e. to start the pull out before releasing. Only once in my log do I mention the squadron having achieved a significant number of hits.

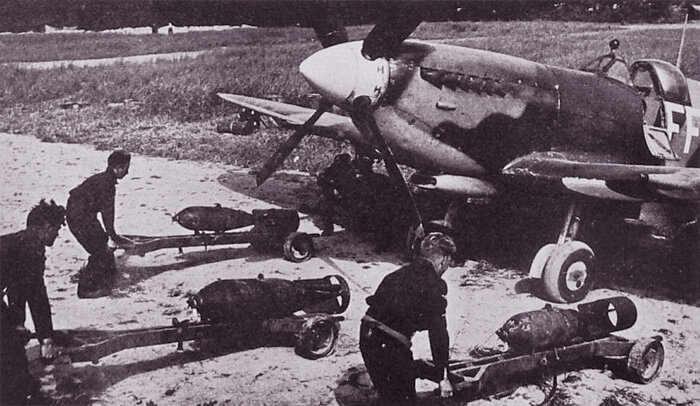

When author Bill McRae was employing his newly learned dive-bombing skills in France against V-1 launch sites and other targets with 401 Squadron RCAF, his old squadron, 132 Squadron RAF, was doing the very same. Here, 132 Squadron armourers wheel two 250 lb and a 500 lb bomb to the bomb shackles beneath a waiting Spitfire. Photo via Avia Deja Vu

A pair of 601 County of London Squadron Spitfires accelerate to take off carrying centreline 500 lb bombs for targets in Italy. A Spitfire of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight is painted in the markings of the all-silver Spit seen in this pair. The BBMF website speaks about the dangers of Spitfire dive-bombing: “There can be no doubt that flying heavily bomb-laden Spitfires on ground attack sorties against a determined, disciplined, and dug-in foe was a very dangerous occupation. Consequently, many brave and skilled pilots of 244 Wing were lost over Northern Italy during the last hard-fought months of World War Two. Many of these men are now buried in the war cemeteries dotted around the Po valley, Ravenna, Venice, and Bologna, but many more still remain undiscovered along with the wreckage of their aircraft. Much less has been written about the Italy campaign than about the advance through northern Europe following D-Day, but there can be little doubt that the Italy campaign was an equally grim and bloody struggle to victory.” Photo via Battle of Britain Memorial Flight

In May of 1944, armourers wrangle a 500 lb bomb to the centreline shackles of a Royal Air Force Spitfire. RAF Photo

A 250 lb bomb is shackled to the hard-point under the port wing of a Spitfire. It was not uncommon, as related by McRae, to have one or even both bombs fail to release when desired. RAF Photo

A fully-bombed up Spitfire warms up before an operation after the D-Day landings.

The first indication of problems came when our crews began painting a white and a yellow line on the inboard chord of the ailerons. This, we were told, was to enable us to watch for and take action in the event of "aileron up-float". This phenomenon had been known to the brass for at least a year, but it was news to us. Apparently at high speeds both ailerons would rise, or float, and if allowed to continue could theoretically reach the point where they would break off. When first discovered on the Mk V, a suggested solution was to droop both ailerons 5/8” at rest, so they could rise to neutral at high speed! In our case we were told to monitor the ailerons as the speed increased; if the white line appeared you were approaching the critical point, if the yellow line showed you were to slow down! At the same time we were supposed to keep the airspeed below the Vne. Obviously we were far too busy trying to keep the target in sight, with red and white balls (AAA) going past us in the opposite direction, to be checking the ailerons and the airspeed while in the dive, so both of these limiting factors were simply ignored. Reaching an indicated AS of 500 mph was not uncommon.

On my first dive-bombing show I went through the procedure, pulled out with great difficulty, blacked out, to recover back up about where I started. On the way home I noticed several guys for a while dipping one wing while looking in my direction, so I did the same but could see nothing of interest. On landing back at RAF Tangmere they told me they were looking at my bomb, which had hung up, eventually falling off. I could not help wondering if they would have enlightened me before I began my landing approach had it not fallen off! That would not be the last time I had a hang-up, at least in MH887, and there were interim occasions when I was unable to get rid of the "cigar tank", I can’t think of anything more nerve-wracking than flying through flack with a thin skinned belly tank, half full, under one’s seat!

My last bomb scare with MH885, just prior to D-Day was when we were sent out to bomb a rail yard close to Dieppe. Because of the vicinity to the guns of Dieppe we were told not to climb back up, but to continue the dive, just clearing the cliffs and then out to sea. This we did, and as I and my Number Two leveled off about 50 feet off the sea I could see flack coming at us from Dieppe, but we were going at such high speed it was all going behind us. Then I felt at tremendous uplift, and looking back saw a huge geyser of water where I had been an instant before. I thought it must have been a large artillery shell, but we were rapidly leaving Dieppe behind so gave it no more thought. Back at Tangmere, my Number Two told me that my bomb had hung up and fallen off as I made the last move to level off over the sea, exploding where I had been seconds before. This was the last straw. I went storming off to the Engineering Officer demanding something be done about this machine's reluctance to part with armaments. What I got was a plunger through the floor which I was supposed to use to kick off a hang-up, providing of course someone told me it as there! I later learned that I was by no means the only one to be provided with this Rube Goldberg "solution"!

I believe the training we had with small smoke bombs was inadequate, especially since we were not told what to expect when dealing with the real thing. Consequently we each had our own idea how to go about it. Initially I trimmed out for the dive then tried to trim out while pulling out of the dive. It usually took both hands on the stick, pulling with all my strength to get out of the dive. A day later I watched as another of our pilots appeared to be pulling out, then the dive steepened, past the vertical, and he plowed right into the ground. The day after that Gerry Billing came back with his Spit wrinkled out of shape; he had tried everything to pull out, then resorted to full rudder, finally pulling out with his aircraft flying through debris from the blast, a wrinkled wreck.

After that I used both hands to hold the Spit in the dive, not trimmed; on releasing the bomb I would let go of the stick, the Spit pulled out of the dive violently, blacking me out, and I would come to hanging on my prop at starting height. This was later frowned on, as Spit wings increasingly were found to have wrinkled wings.

There was another experiment conducted by 401, which several pilots claim to have conducted, but I can accurately say the final one was made by Bob Hayward, since I flew alongside him to observe. The task was to determine whether a 1,000 lb bomb could be dropped from a Spitfire's belly. With me off his starboard wing, he climbed to height, then went into a dive with me diving just off his wing. I know this sounds unbelievable, and I probably would not have believed it had I not seen it, but the bomb, when released, seemed to turn parallel to the wings, then stayed there while the belly of the Spit passed over it, before the bomb fell clear. The evidence was clear when Bob landed; the whole belly of the Spit was crushed, right back to the roundel. That was the last we saw of the thousand pounder experiment.

In my opinion our efforts at dive-bombing were almost a complete failure; we were unable to achieve the precise bombing that our small targets called for. Had we been given area targets, such as marshalling yards or troop concentrations, we could have made a better contribution.

The author, Bill McRae, with his squadron in 1944.

Another good friend of Vintage Wings of Canada is Barry Needham of Saskatchewan, himself an experienced Spitfire pilot of the Second World War with 412 Squadron RCAF. Barryl writes: Your most recent article Spitfire Dive Bombing by Bill McCrae sent me scurrying to my log book. April and May 1944 showed a busy time preparing for the anticipated D day. I managed to chalk up 40 hours of ops including 15 dive bombing sorties. Hurtling down at a 70 degree dive angle at 500plus miles per hour set up a violent vibration making the controls almost immovable. We called this combressibility not realizing that we were approaching the speed of sound.

Another incident was when they tried a 1,000 pound bomb. I recall seeing the bomb fin scrapping the runway as the Ppit taxied by for takeoff. I think this ended the experiment. Scotty Murray of 401 Squadron was probably the first one to experience a bomb hang-up. At the briefing, the question was asked what to do if your bomb does not release? The answer was bale out! On April 19 that is exactly what happened. After unsuccessfully trying violent aerobatics, the bomb was still there, so Scotty took to the silk. Despite being trimmed to reach the Channel his Spit crashed in an open field. Ironically, the bomb failed to explode.

This story was previously published in the Observair Newsletter of the Ottawa Chapter of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, of which the author Bill McRae was a proud member and strong contributor.