THOSE CANADIAN FOKKERS

By the end of the Great War, military aviation had come of age and was recognized as a vital part of modern warfare. The Armistice of November 11th 1918 required the German Army to surrender its most potent weapons of war, so as to discourage the high command from resuming hostilities. This agreement demanded the German army turn over 5,000 artillery pieces, 25,000 machine guns, 3,000 trench mortars, as well as “1,700 pursuit and bombardment airplanes, preference being given to all of the D-7s [sic] and all of the night bombardment machines”. As a result, by the opening months of 1919, 792 Fokker D.VIIs had been surrendered to the British, French, Belgian and American armies. Several dozen of these machines ultimately found their way to Canada, and yet the details of exactly how that happened have been all but forgotten.

From a Canadian perspective, the First World War was a pivotal moment in terms of establishing a sense of nationhood. Thousands of Canadians fought with distinction in the British flying services during the war. On the ground, the Dominion of Canada fielded its first Army-sized formation – the four, over-gunned divisions of the Canadian Corps. To publicize this significant contribution to the allied war effort, Lord Beaverbrook created a public relations machine called the Canadian War Records Office (CWRO). Working with him to construct and preserve a national memory of the war years was Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist and Director of War Trophies. Drawing largely on spoils of war surrendered after the Armistice, Doughty amassed an artefact collection including nearly fifty aircraft. Along with the rest of the trophy collection, these state of the art aeroplanes were intended to form the nucleus of a national war museum in Ottawa to commemorate Canada’s wartime sacrifices.

During the opening months of 1919, Doughty and a young Canadian staff officer by the name of Captain R.E. Lloyd Lott persuaded the RAF and the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to share a portion of their aeronautical booty with Canada. In February and March of 1919, the recently formed Canadian Air Force (CAF) took possession of twenty Fokker D.VIIs from the RAF. The original intent was for the CAF to pack the aircraft for shipment to Canada, but No. 1 Fighter Squadron also flew them extensively alongside their standard British service machines. In part, this was because the experienced Canadian airmen felt that the D.VII was superior to their issued Sopwith Dolphins.

Today, assessing the degree to which the CAF utilized German aircraft is based on a number of primary sources. Among the most useful documentary evidence is a handful of surviving pilot logbooks. In addition to these, a number of official Canadian photographs – one of the many products of Beaverbrook’s CWRO - captured Fokker D.VIIs in CAF custody. In the spring of 1919, CWRO cameramen visited the CAF at Hounslow Airfield (southwest of London, between the modern Heathrow Airport and Kew Gardens) where they photographed Fokkers D.VIIs being used by Canadian airmen. A number of these photographs have since been published fairly widely, yet their Canadian connection is most often entirely overlooked.

The photograph showing a line-up of four Fokker D.VIIs (the nearest bearing the ‘RK’ insignia of Richard Kraut from Jasta 63) has appeared in a number of publications. Some rightly identify the location as Hounslow, but never has a caption indentified the serials of all four aircraft in the photograph, nor has anyone noted that they were being utilized by the CAF. Through an examination of original CWRO albums held at the Canadian War Museum (CWM), and an appreciation of context in which the photos were taken this author has deduced much information about the images in this series. Two other photographs of this same foursome, taken from different angles and showing a handful of CAF members, allow the four aircraft to be identified as Albatros-built D.VIIs bearing the serials 5924/18 [often misidentified as 5324], 6769/18, 6810/18 [the so-called ‘Knowlton Fokker’ that survives in Canada to this day at the Brome County Historical Society] and 6822/18. In order to extract this information, one requires access to all three photographs, an appreciation of their relationship to one another, and good quality scans or prints from the original glass plate negatives.

Taken at Hounslow airfield, this CWRO photograph shows Albatros built Fokker D.VIIs 5924/18, 6769/18, 6810/18 and 6822/18 after the RAF presented them to Canada for its collection of war trophies.

Another view of the same foursome of Fokkers, with a handful of CAF members. The nearest aircraft is identifiable as 6822/18.

The third and final photograph in the series depicting the four Canadian D.VIIs in Hounslow. The maple leaf cap badges of the ground crew clearly indicate that they were drawn from the Canadian Expeditionary Force. This image also confirms the identity of the third aircraft in the line-up – 6810/18 (number visible at far left) – as the well-known ‘Knowlton Fokker’.

Related Stories

Click on image

One of these three photographs (the long shot of all four machines) can be found in the image collection at the Imperial War Museum (IWM). Copies of most official CWRO photographs were provided to the nascent IWM after the war, although the post-war CAF shots appear not to have been included. LCol Kimbrough S Brown of the United States Air Force donated the lone Hounslow image to the IWM. He likely acquired it in 1953 after his attention was drawn to topic of Fokkers in Canada by the article ‘Achtung-D.VII’ in the RCAF’s Roundel magazine. In isolation, it is understandable that researchers who encounter this image of four Fokker D.VIIs are hard pressed to identify its Canadian connection, or to determine the identity of all four aircraft. .

A similar example of a CWRO photograph that has been imprecisely or incorrectly identified is the close-up of ‘RK’ [5924/18] with an airman in flying gear about to climb into the cockpit. In the past, this fellow has been identified as Richard Kraut, Rudolf Klimke and as an unidentified British pilot. Only the last one bears any truth, as it is actually a well-known Canadian airman who flew Fokker D.VIIs extensively while they were in CAF custody during early 1919. The gentleman in this photograph is none other than the Commanding Officer of No 1 Sqn CAF, Andrew McKeever, DSC, MC and Bar – the highest scoring pilot on the Bristol F 2B. McKeever’s proclivity to be photographed with the war trophy aircraft is reiterated by a better-known image of him against the lower wing of a D.VII, bearing the logo of No. 1 Squadron CAF (a green maple leaf outlined in white and overlaid with a white ‘1’). During two CRWO visits to the CAF, Captain A.E. McKeever was photographed at least five times with various Fokker D.VIIs. Yet there is another famous Canadian airman that had an even closer relationship with the Fokkers, both in Britain and after their shipment to Canada.

This often mis-identified photograph is actually Andrew McKeever, the successful Bristol F2 B ace, climbing into Fokker D.VII (Alb) 5924/18 at Hounslow. He flew captured Fokkers extensively while they were in the custody of the CAF.

Captain A.E. McKeever stands beside Fokker D.VII (OAW) 8493/18 while it was in the custody of No. 1 Squadron, Canadian Air Force at Upper Heyford.

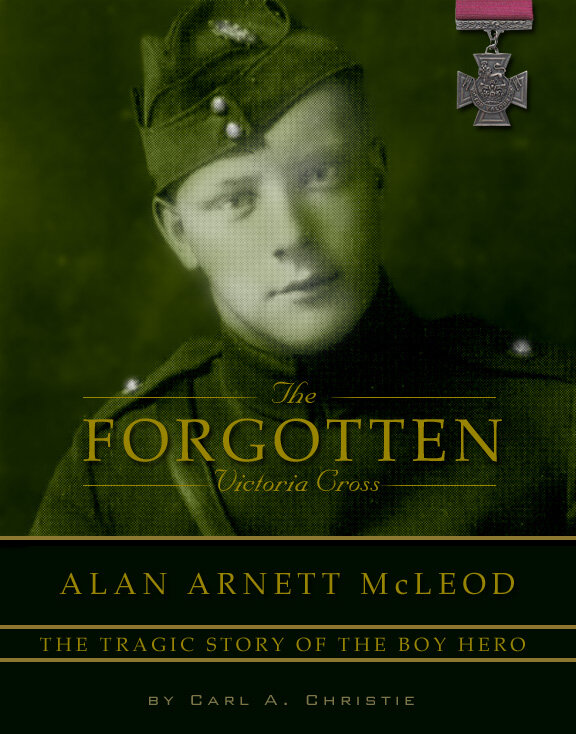

In addition to the War Records Office, Lord Beaverbrook also orchestrated the Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF). This was a scheme that utilized gate revenues from at exhibits of CWRO photographs to fund a program of commissioned paintings commemorating Canada’s contribution to the war. While Captain Lott and Arthur Doughty were negotiating for a share of the war trophy aircraft in January and February of 1919, Beaverbrook’s paintings were on display in London’s Royal Academy of Art at Burlington House. In addition to German aircraft, Doughty also managed to acquire the fuselage of Sopwith Snipe E8102 for the trophy collection. This was the aircraft that William George Barker flew in an epic fight against innumerable Fokker D.VIIs - for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Staff at the CWRO again coordinated a conscious publicity exercise when they photographed Barker next to his Snipe while it was on display alongside CWMF art at Burlington house. In an interesting parallel, C.R.W. Nevinson’s “War in the Air” (a painting produced for the CWMF, and displayed in Burlington house during early 1919), presently hangs directly above the fuselage of Snipe E8102 in the Canadian War Museum.

Sopwith Snipe E8102, shortly after William Barker flew it in his VC-winning action of 27 October 1918. Taken in France, this image illustrates the minimal damage incurred after Barker overturned the machine on landing.

Barker standing next to the fuselage of Snipe E8102 at the Canadian War Memorials Fund exhibition held in Burlington House, London during January and February of 1919. [Note he is still recovering from his injuries - Ed]

Men from Beaverbrook’s Canadian War Records Office once again visited Hounslow on the 20th of April 1919, with their cameras at the ready. By this point, the wounds William Barker suffered in his VC-winning fight had sufficiently healed to allow him back into the cockpit of an aircraft. After first flying an AVRO 504K trainer, the CAF Fokkers quickly aroused his interest. Undoubtedly, his curiosity was piqued in part because this was the type of machine against which he had fought for his life on the 27th of October 1918. Barker proceeded, not only to check himself out in Fokker D.VII F 7728/18 (the pre-eminent fighter of the day), but the accompanying photograph shows him ‘stunting’ in the machine over Hounslow Airfield. Over the next two months, the CAF began preparations for demobilization, which was expected to happen near the end of July. In addition to keeping up regular training, a CAF detachment at Chingford packed the remaining war trophy aircraft, along with Barker’s Snipe and shipped them to Canada.

William Barker standing next to another Canadian trophy aircraft, Fokker D.VII F 7728/18, at Hounslow airfield on the 20th of April 1919.

This excellent aerial view of Hounslow Airfield was taken on the same day as figure 8 and shows Barker pulling into a loop as he ‘stunts’ in 7728/18 over the field.

After the crates were unloaded from ships in Montreal, they were forwarded to Toronto by rail. Once there, Arthur Doughty intended to display them as part of the ‘Victory Year’ celebrations at the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) during the last two weeks of August. Artillery pieces, machine guns and other trophies were sent directly to the Exhibition Grounds while the aircraft were sent to Leaside airfield in northeast Toronto. The CAF consisted entirely of the two Squadrons in England and thus, there was no Air Force in Canada to take possession of the German aircraft. Two private companies filled the void, supporting Doughty and his staff from the Public Archives Department in handling the trophy aircraft. F.G. Ericson not only agreed to lease hangar space to Doughty at Leaside, but his employees assembled a handful of the Fokkers. These included factory-new examples such as 8609/18 that had been claimed directly from the Ostdeutschen Albatros Werken (OAW) factory by the AEF - as indicated by the lack of fuselage and rudder crosses. Pilots from Bishop-Barker Aeroplanes Limited (BBAL), a company run by the two surviving Canadian air VC winners, began flying operations with Fokker D.VIIs over Toronto in preparation for an air display during the CNE.

This fascinating photograph was taken in late summer 1919 and shows Barker sitting in E8102 - literally surrounded with German aircraft in a hangar at Leaside Aerodrome in Toronto. Looking through the Snipe’s centre-section is Arthur Doughty, the Director of War Trophies and standing at left is F.G. Ericson, the entrepreneur and engineer who controlled Leaside immediately after the war.

Fokker D.VII (OAW) 8609/18 sits outside a hangar in Leaside, assembled and ready to be flown by the pilots of Bishop-Barker Aeroplanes Limited.

Throughout the Exhibition, BBAL pilots put on displays of formation aerobatics and ‘sham fights’ that received rave reviews in newspapers across the province. In effect, 1919 was the first CNE Air Show, even though the modern Canadian International Air Show (CIAS) only traces its lineage to the 1949. The Aero Club of Canada organized an air race between Toronto and New York City during the first week of the CNE. Making good use of the cutting edge fighters Doughty had loaned to BBAL, Barker had a large white ‘50’ (his race number) painted in several places on one of the new OAW-built Fokker, and entered himself in the competition. Before and after the race, Barker’s air displays at the CNE and elsewhere in the later half of 1919 exposed spectators to ‘war in the air’. At the same time, Doughty’s large display of trophies allowed the public an up-close experience with the spoils of war. In addition to highly symbolic captured German artillery and machine guns, the displays included static aircraft and German militaria of literally all sorts. Also on display at the CNE were the products of Beaverbrook’s promotional efforts - CWRO photographs and CWMF paintings filled a building adjacent the trophy display.

Taken at Armour Heights, another airfield built during the war in Toronto, William Barker is running up the Mercedes engine in the Fokker D.VII that he flew during the Toronto-New York Air Race of August 1919. The large ‘50’ painted on the underside of the wings and fuselage was his race number.

A similar, although much expanded display of trophies was showcased to the public at the Hamilton Armouries for two weeks surrounding Armistice Day (as Remembrance Day was originally known) in November 1919. Photographs of this exhibition are particularly interesting because they include three of the four most significant First World War ear aircraft that have survived in Canada to the present. On the right, is the fuselage of Barker’s Snipe - E8102. Its Bentley BR 2 engine accompanied it while on display in Burlington house, and was shipped to Canada, but was lost in transit somewhere between Montreal and Toronto. At the far end of the hall is A.E.G. G.IV 574/18 and in the near right corner is the all-metal Junkers J.1 [J4] 586/18 – both of which are now held by the Canada Aviation Museum in Ottawa.

Arthur Doughty displayed a wide range of war trophies in the Hamilton Armouries for several weeks surrounding Armistice Day in 1919. This particularly clear photograph shows an unidentified Fokker D.VII (likely 8474/18), A.E.G. G.IV 574/18, Junkers J.1 [J4] 586/18 and Snipe E8102 – fortunately, the last three survive in Ottawa to this day.

The vast majority of German aircraft shipped to Canada were Fokker D.VIIs, and yet only one of them is extant today. Fokker D.VII (Alb) 6810/18, the third aircraft in the above-described Hounslow foursome, has been on display at the Brome County Historical Society (BCHS) of Knowlton, Quebec since 1921. 6810/18, and a handful of other D.VIIs, escaped immediate destruction because they were distributed to various Universities and the BCHS. In November of 1921, 5924/18 (bearing the ‘RK’ insignia) and the remaining D.VIIs were transferred to the custody of the Canadian Air Board. Acting on direction from the Superintendant of Flying Operations, Lt Col Robert Leckie, most of the war trophy aircraft were unceremoniously ‘reduced to produce’ – scrapped. Close examination of the disheartening photo showing D.VII fuselages stacked like firewood will reveal white and black stripes running across the belly fabric of the aircraft in the foreground. The lower half of digits ‘92’ are also barely visible on the curled piece of fabric just aft of where the fuselage cross once adorned the side of ‘RK’. Rather than a prominent place in a national war museum, most of Doughty’s trophy aircraft met an ignominious end, as illustrated by this final image of 5924/18.

Unidentified workers sitting on the fuselage of Fokker D.VII (Alb) 5924/18, ‘RK’ while it is being scrapping along with at least five other D.VIIs at the orders of Lt Col Robert Leckie of the Canadian Air Board in late 1921.

For many reasons, there was no Canadian War Museum until 1942 and no permanent aviation museum on a national scale until 1968. Both of these institutions ultimately incorporated artefacts that were preserved thanks primarily to Doughty’s efforts to preserve memory of the Great War in Canada. Despite the wanton destruction of war trophies by Leckie and the Air Board, Knowlton’s 6810/18, the AEG, Junkers and Barkers Snipe remain national treasures and a credit to Doughty’s efforts in 1919.

By Edward Peter Soye

Author Soye comissioned a painting by Russell Smith depicting Barker (in blue uniform) and employees of the BBAL examining the Fokkers at Armour Heights in Toronto after the war. For more information on the painting and soon-to-be-released giclé prints visit Russell Smith's website.

Edward Peter Soye completed his undergraduate studies in history at the University of Toronto in 2007. In May of 2009, he graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada with a Masters in War Studies. This article represents a small sample of the research and analysis that went into Edward’s MA thesis, Canadian War Trophies: Arthur Doughty and German Aircraft Allocated to Canada after the First World War.

Born and raised in the Greater Toronto Area, Edward is currently employed by an investment management firm. Beyond academia and work, pursuing his passion for flying occupies most of Edward’s free time. He is actively involved with the Air Cadet Gliding Program as both an instructor and tow pilot. In terms of vintage aircraft, Edward has flown a number of First World War replicas and regularly flies with the Canadian Harvard Aircraft Association in Tillsonburg. He can be reached at edward.soye@gmail.com

Postscript: Additional photos

Fokker D.VII 6810/18, The Knowlton Fokker, now resides at the Brome County Historical Society's museum in Knowlton, Quebec. Photo J.P. Bonin

The aforementioned Allgemeine Elektrizitäts Gesellschaft (A.E.G.) G.IV which was displayed at the Hamilton Armouries in 1919 now resides at the Canada Aviation Museum - the only German twin-engine military aircraft of the First World War still in existence. It was shipped as a war trophy to Canada in 1919; its movements over the next 40 years (two 260 hp Mercedes engines were lost) were not well documented. The aircraft was stored in a warehouse operated by the Canadian War Museum in the 1950s. In 1968-69, it was restored by No. 6 Repair Depot, RCAF, with 160 hp Mercedes engines in place of the correct powerplants. Info via CAM, Photo Tom Podolec

The Junkers J.1 was the world's first practical all-metal aircraft to enter mass production. Of the 227 built, only one exists today - the same one exhibited by Arthur Doughty at the Hamilton Armouries in 1919 and now on display at the Canada Aviation Museum.

C.R.W. Nevinson’s “War in the Air” (a painting produced for the CWMF, and displayed in Burlington house during early 1919), presently hangs directly above the fuselage of Snipe E8102 in the Canadian War Museum. Nevinson depicts an air battle involving Canadian air ace, William 'Billy' Bishop. Bishop's plane, with blue, white and red roundel and tail markings, fights at least three German aircraft. Bishop, the second-highest ranking Allied ace of the war, was credited with the destruction of 72 enemy aircraft. Image via Canadian War Museum

Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist and Director of War Trophies. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

An aerial view of Armour Heights airfield, mentioned in Soye's story. Bishop-Barker Aeroplanes Limited operated from the airfield immediately after the war. After the collapse of the company in the summer of 1921, the airfield fell into disuse. It is now the site of the Canadian Forces College in Toronto. Photo: DND

![Barker standing next to the fuselage of Snipe E8102 at the Canadian War Memorials Fund exhibition held in Burlington House, London during January and February of 1919. [Note he is still recovering from his injuries - Ed]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1630073358006-O52PCJWIMVUT1HWBK4GT/Fokkers8.jpg)