LIFTING THE DEAD — The Bud Larson Story

The end of the Second World War meant many things to the pilots of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). It meant going home, eating mom’s cooking once again, breathing that particularly crisp, and powerfully euphoric, Canadian air. It meant, for some, riding a train across the very country they had risked their lives to keep. It meant high school sweethearts, small town homecomings, fitting back into a quieter life. For some, it meant college and picking up the dropped reins of a life put on hold. It meant they had lived to see all the sunsets and sunrises they were entitled to—25,000 for some, still living today. Some of these men, a fraction, would remain in the RCAF and live to fight and even die in the Cold War. But for the great majority of airmen and airwomen, it simply meant returning to the life they put on hold, to those they loved and applying the hard won lessons of duty, honour and sacrifice to everyday life. These men and women built the Canada we know today. They created Canada’s personality—a polite non-bragging people, who were hard-working, in tune with their communities, capable of great kindness, yet potentially lethal to those who would threaten freedom, democracy or equality. They were known as the Silent Generation and sometimes the Greatest Generation. The generations that followed—the Baby Boomers, Generations X, Y and Z, the Millennials—have somehow lost some of that greatness, that silence. Under threat of disappearing altogether is that quiet, walking-tall, honourable, friendly Canadian who puts community ahead of all other values—replaced by a society of individuals that value fame and self-gratification above all else. Special interests, the media, and the internet have progressively diminished, eroded, exploited and drugged us until we have begun to think of duty, honour and sacrifice as old-fashioned.

Here is a story of a small town prairie kid, who became one of the elite aviators of the Second World War. He got there, not by self-aggrandizement, lone-wolfery or by stepping on people. He became the decorated man that he is by being very good at what he was trained to do—to think, to think fast, and above all to make the right decision at a critical time. He was a member of a team, a community of top aviators. He was a Pathfinder. This Pathfinder had many hairier episodes in his two-tour Bomber Command career, but this simple story speaks to the superb training of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan—a massive nationwide system to find, recruit, select, train and test the best of the best our country could offer. Like a larger multi-layered social filter, the BCATP allowed only the truly great to make it to the end—the pilots, navigators, flight engineers, bomb-aimers, gunners, radio operators, mechanics and technicians of the RCAF, RAAF, RNZAF and RAF.

Lifting the Dead

It wasn’t much really. Hardly noticeable at first as he thundered down Runway 22 Left. A slight change in the vibration of the controls. If it was your first time climbing a fully-loaded Lancaster, you might have noticed it too late. But this pilot, Flight Lieutenant Lyle Erling “Bud” Larson, knew right away—felt it come up from the main spar, up through the control column, sensed the vibration through the Bakelite of the yoke. Larson’s trained eyes scanned the instruments, squinting through the late afternoon sunlight pouring in as he climbed out to the west. A second sense, born of more than 50 combat missions, told him something wasn’t right.

It was 9 April 1945. The time of day was 1613 hours GMT. Though the Second World War was showing signs of winding to a close with the Allied juggernaut gaining an unstoppable momentum, backed by the massive war production machine in North America, the tempo of combat flying in the Royal Canadian Air Force’s elite Pathfinder unit—405 Squadron—was, if anything, only increasing. The 405 Pathfinder aircrews were now flying up to four operations a week, and as the Nazis reeled backwards, all the flying took 405 deep into the German heartland. Bud, a seasoned veteran at just 23 years old, had been training for or fighting at war for nearly five long years. The shy farm kid from Cabri, Saskatchewan had become a gifted pilot, seasoned combat flier and a veteran leader. His skills had made him one of Bomber Command’s elite—the Pathfinders.

The 405 Pathfinders Squadron operations and planning room at RAF Gransden Lodge, about 16 kilometres west of Cambridge, England. In this busy and smoke-filled room, missions were planned down to the smallest detail, taking into account all variables such as fuel, daily signals, meteorology, intelligence, German defences and bomb fusing times. After planning, the squadron assembled for a briefing before being driven to their aircraft. Photo: RCAF

The Pathfinders were target marking squadrons of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command during the Second World War. They were responsible for lead navigation, locating and marking specific targets with flares or incendiaries, which the following main bomber force could then aim at, increasing the accuracy of the overall bombing. As such, the Pathfinder crews, particularly the pilots, navigators and bomb aimers, were the best of the best.

Avro Lancaster “D” for “Dog” was dead last in a stream takeoff from RAF Gransden Lodge. Ahead of LQ-D, in the low sunlight, were the silhouettes of a dozen other 405 Squadron Lancs, straining under heavy loads to gain a safe altitude. Bud’s Lancaster had reached takeoff speed, all of its engines straining at maximum power, all except for one. There was no aborting this takeoff now. Pulling back on the yoke, Bud willed the big bomber off the runway.

A fully loaded 9 Squadron Avro Lancaster Mk III struggles into the air on a night raid to bomb the Zeppelin works at Friedrichshafen, Germany. Losing an engine at this point is the worst possible time—with a full load of bombs and incendiaries, seven hours worth of gasoline on board, all three of the other engines already making full power, no more runway and obstacles ahead. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Related Stories

Click on image

The Lancaster was a formidable heavy lifter. While the Yanks in their B-17 Flying Fortresses could carry 4,500 lbs of high explosive bombs all the way to Berlin, the Lancaster could carry three times that weight—14,000 pounds! Specially equipped Lancs could carry a 22,000 lb Grand Slam bomb for special operations against submarine pens.

Now, with Runway 22 Left behind him, and carrying a full bomb load of 14,000 lbs of high explosive and incendiaries for targets in the city of Kiel and massive gas tanks full of high octane aviation gas, all of Bud’s training, all his experience, all his hard-won knowledge, would be focused on a split second decision. The decision was irrevocable and it had to be right. Kiel would have to wait.

As the heavy aircraft struggled through 150 feet altitude, Bud took a glance to his right and could see the oil pressure on his Number 4 engine dropping, the needle rolling back, flickering dangerously. “Damn…” thought Larson to himself, careful to keep his fears to himself. With the ground looking uncomfortably close, and the aircraft straining hard under the failing engine, Larson snapped a quick peek, across the chest of his engineer Al Potter, through the Perspex of the cockpit and over the number three engine. What he saw drained the blood from his face. Blue-yellow flames were streaming from Number 4’s exhaust manifold. Somewhere inside the wailing guts of that engine, in the labyrinth of lines, clamps and pipes, a gasket had blown or oil line had ruptured. Under pressure, oil was ignited and was blow torching from the exhaust stacks.

As Larson climbed out of Gransden Lodge with his No. 4 engine about to pack it in, he would have been focused on maintaining his climb and monitoring his airspeed indicator and the RPM and Boost on his No. 4 (starboard outer) engine. During climb out, his Flight Engineer, Al Potter, would have been sitting right beside him on a fold-down jump seat, giving him readings and information. Just above the throttle quadrant, and in front of the engineer in this digital recreation, we see numerous dials and switches, set up in banks of four. Digital recreation of the cockpit of a Lancaster by Polish digital art phenom, Piotr Forkasiewicz

The No. 4 engine of a Lancaster bomber, like its three wing mates, was a powerful, sophisticated and complex machine. A myriad of electrical wires, fuel and glycol lines, twelve pistons and a heavy camshaft thrashing about in oil. As good as the engine was, there was much chance for something to go awry. The last place aircrews wanted a problem was at the end of the takeoff roll. Photo: Todd Lemieux

There’s never a good time for an engine failure when flying an aircraft, any aircraft. But there are times that are worse than others. The worst possible time for engine failure to occur on any aircraft is during takeoff, in particular that period just after liftoff and prior to attaining the magic figure still usually called “safety speed”. This is the speed at which it is still possible to keep the aircraft under control and flying, and preferably still climbing. If you have not attained this safety speed, then your only option is to execute a textbook straight-ahead forced landing. With low light, small farm fields surrounded by hedgerows of high trees, scattered small villages, raised dykes and any number of unseen obstructions dead ahead—and, for tactical reasons, unable to use landing lights—Larson knew that a forced landing with a full load of fuel and a belly full of high explosive ordnance was a death sentence for all seven airmen onboard.

A fully loaded Avro Lancaster requires a recommended minimum “takeoff speed” of 95 mph indicated (IAS). Really, a pilot needs to get her to 105 mph with the tail up, wings level with the ground and moving enough air over the wings to get airborne. And herein lies the rub. It just distills down to a case of mathematics. 105 and you are flying, but not until 130 are you safe to continue to fly. Between 105 and 130 stands 25 mph of uncertainty, even with four engines. Without 130 over the broad wings of the Lanc, Larson could not begin to contemplate a turn. Turning before would doom his men, himself. Every second that passed, every mile-per-hour won, was a thing of great significance, a thing of beauty.

Seconds, milliseconds, instants. Larson had little time to make a decision. The difference between a bad decision and a good decision was Larson’s training. He was faced with two choices: he could shut down the No. 4 Engine, extinguish the fire and feather the prop immediately, or let it torch longer and squeeze what little failing thrust was still in those dying cylinders to get him to that magic 130 mph number. Let it go longer and the blow torch fire could burn through the wing and the fuel tanks it housed. Shut it down and he would lose what little thrust it still generated. Larson watched the fire carefully, knowing he needed everything left from No. 4, needed every fraction of accumulating airspeed. He would nail 130 on his airspeed indicator first, and then go through the shut down sequence. His training gave him the confidence to make the right choice.

Holding her steady, advising the crew of the situation and his decision, and concentrating on flying his performance-degraded heavy bomber required every ounce of Bud Larson’s concentration. “Come on, come on, come on”, he thought to himself as he willed the airspeed indicator to climb.

Bud Larson did not get to the command seat of a Pathfinder Lancaster through seniority, luck or nepotism. He was here, in this terrifying moment and making the right choices, because he was a total professional. A gifted pilot and leader yes, but a professional who took his training to heart and applied it every day. Derring-do and bold lone-wolf independent acts might happen now and then, even inspire, but only training, teamwork and professionalism would win this war. It was this accumulation of training—absorbed, repeated, applied, repeated and applied again since his 1940 enlistment—that made Bud the pilot that he was. A product of the massive, complex and selective British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a national training program that suffered no fools nor graduated the incompetent, Bud Larson was very much on top of his game. This day he would need to be.

Bud (in civilian clothes) and his brother Lloyd pose in the front garden of the family home in Saskatchewan. Lloyd joined the RCAF and qualified as a Navigator, but a diagnosis of stomach ulcers resulted in the loss of his flying status. He sat out the war in Cabri, helping to run the Larson family butcher shop. Bud Larson could not be much older than 20 in this photograph, but looks much older than his age. Today, well into his 90s, he looks much younger than his age. Photo: Larson Family

Young Lyle “Bud” Larson joined the RCAF from his Cabri, Saskatchewan home in 1940 and was selected for aircrew training. He completed his Elementary Flying Training syllabus at No. 6 EFTS, Prince Albert, Saskatchewan flying the Tiger Moth, and was selected for further multi-engine Service Flying Training. Like all the young students completing their EFTS flights, Bud likely hoped to be sent to a single-engine Service Flying Training School (SFTS) where wings earned on the North American Harvard would likely get them to a fighter unit overseas. To a man, young student pilots wanted to be fighter pilots, but when they were chosen instead for multi-engine, they got over their disappointment and got down to learning their new trade. Being a bomber pilot was to face far greater odds for injury, imprisonment or death. He would now need to take his training even more seriously than before. His life would depend heavily on the lessons he would absorb over the next few months.

Leading Aircraftman Bud Larson (left) and two of his flying training classmates pose rather self-consciously with a De Havilland Tiger Moth at No. 6 Elementary Flying Training School at Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. For Larson, doing his training (both Elementary and Service Flying) in his home province meant he could go home the odd weekend to visit family and friends. Most of these men would be far from home—from across Canada, Great Britain and even Australia and New Zealand. Photo: Larson Family

An aerial photograph, looking to the south, of No. 6 Elementary Flying Training School at Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, situated to the north side of the Saskatchewan River. Flying over Saskatchewan farm fields was like flying over home to young Bud Larson. Photo: RCAF

Larson would build his knowledge and flying hours, and then win his coveted RCAF pilot’s wings on the Cessna Crane (called the Bobcat in the US) at No. 4 SFTS in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. His instructors at Saskatoon taught him very well. Each would be counting the days until their instructor duty came to an end and they too would be sent overseas to join a bomber unit. The lessons that they imparted to Larson, they took personally. With a heavily laden bomber, no lesson was more important than engine failure procedures. With each student they drilled and re-drilled engine failure lessons constantly, until it was second nature.

Cessna Cranes of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan over the Canadian Prairie. It would be this training at No. 4 SFTS that turned Bud into a true professional, capable of handling the Lancaster under less than ideal conditions. Photo: RCAF via Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

All of Larson’s hard-earned training was coming home to roost during these few critical seconds in the failing light over Cambridgeshire. Time was slowing down. As in all these life-and-death situations, it seemed like an eternity to Bud (and no doubt his crew) though it couldn’t have been more than a minute. Calmly Bud held her steady, while Potter kept an eye on the fire situation in No. 4. Imperceptibly, but steadily, the airspeed began to creep towards 130 mph. “The magic number!” he thought to himself when the needle on the indicator flickered over 130. Not wanting to make any brash moves, he began a creeping, tentative banked turn to the left. In the back of his mind he could hear his Crane instructor’s memorable words—“Lift the Dead, Larson, Lift the Dead.” With this mnemonic, he learned to always bank away from the dead engine, to fight the effects of asymmetric thrust. Tonight, his life and his crew’s were saved by Lifting the Dead.

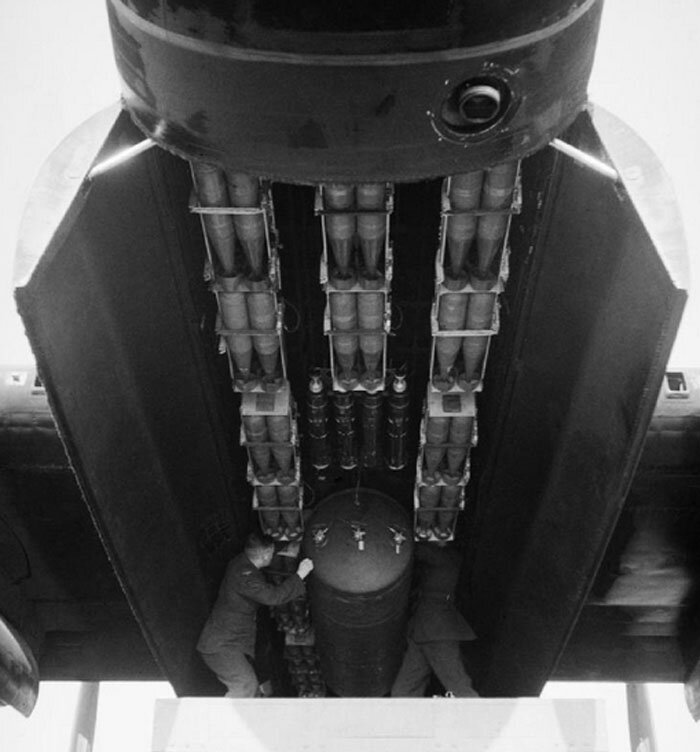

Two Bomber Command armourers make final checks on the bomb load of an Avro Lancaster Mk I of No. 207 Squadron at RAF Syerston, Nottinghamshire, before a night bombing operation to Bremen, Germany. The mixed load (Bomber Command executive codeword ‘Usual’), consists of a 4,000-lb HC bomb (‘cookie’) and small bomb containers (SBCs) filled with 30-lb incendiaries, with the addition of four 250-lb target indicators (TI) in the centre ahead of the cookie. The cookie was regarded as a particularly dangerous load to carry. Due to the airflow over the detonating pistols fitted in the nose, it would often explode even if dropped, i.e. jettisoned, in a supposedly “safe” unarmed state. Safety height above ground for dropping the 4,000 lb “cookie” was 6,000 ft; any lower and the dropping aircraft risked being damaged by the explosion. Photo: Imperial War Museum

As LQ-D turned to the left and slowly gained more altitude, Bud felt it was OK to pull the fire extinguishers on No. 4 and feather the propeller blades. He could feel some of the anxiety releasing from his shoulders. With the other three Merlin engines pulling with maximum power, the Lancaster seemed to groan and vibrate at every joint. Almost home free. Almost. He had one thing he had to do first—get rid of his bomb load. He continued his left turn and steadied on a course for the Thames Estuary some 60–70 miles to the southeast. He would be airborne for about 20 minutes, still in the bomber stream.

Bud held the airplane down low, between 1,000 and 1,500 feet above the ground, to allow for the other bombers, streaming out of England, to climb above his crippled ship. He listened for his navigator to read him a heading, up the Thames to the east to get to the jettison area. Here over a predetermined spot, it was safe to drop his 14,000 pounds of bombs.

A quick glance back to the right confirmed that Number 4 was still feathered and the fire was out. Bud held her steady on course and, passing over the estuary, he reached the drop zone where he could finally “pickle” his bomb load and bend a course for home. There was one last worry. Would all the bombs fall away? This was critical, for not being able to successfully jettison all of the ordnance meant, at minimum a bailout. Landing a bomber with hung bombs could spell disaster. A heavy (or even light) jolt on landing could finally and tragically separate the balky bombs from their shackles. Nobody on this Lancaster wanted to contemplate landing with ordnance onboard.

Below and forward of Larson, the bomb aimer opened the massive bomb doors of the Lancaster, the hydraulics whining imperceptibly beneath the thunder of the engines. Bud felt the controls vibrate as the doors opened into his slipstream. This time it was good news... the bombs fell away in the order they were meant to go over the target. Flares and incendiaries first, followed by the 500 lb iron bombs. The lightened Lancaster surged upward and the controls felt lighter, more responsive. Confident with the three remaining engines, it was time to bank her firmly left, calling the navigator for a vector for Gransden Lodge and home. And a drink.

Ops Kiel was planned for 7:15 flight time. The logbook for the stressful trip records 1:15 of flying time. All the men made it home that night, due to the training and professionalism of its crew, and in particular, its pilot.

Polish master artist Piotr Forkasiewicz painted this digital masterpiece of Bud Larson’s Lancaster LQ-D releasing its bomb load safely in a pre-designated jettison zone east of the mouth of the Thames Estuary. The 14,000 pounds of high explosive and incendiaries can be seen at lower left falling to the English Channel, where they remain to this day. Behind LQ-D, the rest of the bomber stream thunders towards their target. For some of these boys, this was their last sunset. Digital art by Piotr Forkasiewicz

As Larson, in the left seat, bends a course for home, Flight Engineer, Sergeant Al Potter, turns to check the feathered No. 4 Engine. Note the heat blur coming from No. 3 Engine—the artist has thought of everything. Digital art by Piotr Forkasiewicz

A close-up of the dramatic moment when the Larson crew could finally breathe a sigh of relief. Their 14,000 pounds of explosives drop harmlessly to the waters of the English Channel. The propeller blades of No. 4 engine can be seen stopped and feathered and the bomb doors begin to close. Digital art by Piotr Forkasiewicz

Flight Lieutenant Bud Larson

If you managed to complete a full tour of 30 operations with Bomber Command, you had skill, massive steel balls and a whole lot of luck. Bud Larson, completing two full tours, beat the odds—twice. Let’s look at the numbers.

As Second World War dictator Joseph Stalin once said, “Quantity has a Quality all its own.” In no other Allied combat service of the war did this old adage apply quite like the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command. There were 125,000 aircrew members active in Bomber Command during the war. Of these thousands of young men, mostly volunteers, 55,573 were killed on operations, 8,403 were wounded in action and 9,838 became prisoners of war. The death rate was a breathtaking 44.5%. To put this into perspective, the United States Army Air Force’s 8th Air Force—the Mighty Eighth—had 350,000 aircrew members of which 26,000 were killed in combat—a 7.45% death rate, which was a terrible price to pay, but one that pales in comparison to that of Bomber Command. An airman of the Command had a worse chance of surviving the fight than a British officer in the hideous and obscene trench fighting of the First World War. The chance of surviving a full tour of 30 ops with a Bomber Command squadron was down to 16%. Even before operations, men were killed in training before joining Bomber Command—some 5,327 men met their deaths in training accidents alone.

If you randomly picked 100 airmen from the ranks of Bomber Command, 55 would have died on operations or later of their wounds, 3 would have been injured on ops, 12 would have been taken prisoner, 2 would have been shot down but would have evaded capture and only 28 would have survived one tour of operation. A staggering 364,514 operational sorties were flown by aircrews of Bomber Command, dropping more than a million tons of bombs and, in the process of duty, losing 8,325 aircraft of all types. Of the 55,573 men who were killed in action, 18% (more than 10,000) were Canadian boys like Larson and some of his crew.

Bud Larson (right) relaxes with his fellow crew members, Flight Sergeant Bill Little (left) and Sergeant Stan Ford (centre) during a break between missions at RAF Gransden Lodge. The strain of constant operations made fast friends of crew members, while friends in other crews could be lost when their bombers were shot down. Crews tended to build strong bonds. That being said, the crew lists accompanying some of the photos in the Larson collection indicate that many of his crew changed over the period of his full tour. Both Little and Ford were gone by March of 1945 when the Larson crew was attacked and nearly shot down by three night fighters on the night of 7–8 March 1945. Photo: Larson Family

When young Canadian boys left their loving families and sailed the U-boat gauntlet to England to fly in combat and risk their lives, their families, especially their mothers, worried endlessly about them and their welfare. It was common in England to find local families who would “adopt” a Canadian aircrew and invite them into their homes for a much-needed home cooked meal and a friendly atmosphere—even if the family had little of their own. Bud Larson (back left) and his crew are pictured here with their adopted family—the Browns, who lived near 405 Squadron’s base at RAF Gransden Lodge. Pictured at the front are John, Renee and Edna Brown, whose kindnesses towards Larson’s crews help alleviate, in many ways, the powerful homesickness felt by the young aviators. Photo: Larson Family

The Larson Crew was every inch a Bomber Command crew with the crushed mission caps, swagger and camaraderie one would expect from a Pathfinder unit. Here we see them posing in front of their Lanc at RAF Gransden Lodge, and judging from the kit, it’s before or after an “op”. Back row, left to right: Unknown; Davies, Navigator; Bud Larson, Pilot; Whitworth, Gunner; Roy Van Metre, Wireless Operator; Front row, left to right: John Bolen, Bomb-Aimer; Oliver, Gunner. Photo: Larson Family

Another more formal photograph of Larson’s crew. Having flown two full operational tours, some of the faces may be different than the previous shot, but we can identify some: John Bolen, Bomb Aimer (left, sitting), Bud Larson (second from left, sitting), Michael Allan Potter, Flight Engineer and Roy Van Metre, Wireless Operator (right, sitting). Photo: Larson Family

Another crew shot from an unknown time, but likely at Gransden Lodge, including members of the ground crew. Some we can identify: Left to right: Unknown, Unknown, Davies the navigator, Van Metre the Wireless Operator, Larson (looking relaxed and proud of his men), Michael Allan Potter, Flight Engineer, Bolen the Bomb Aimer, unknown, unknown, unknown. Photo: Larson Family

The Larson crew received a rare Target Token certificate for a night raid on the German seaport of Emden on the coast of the North Sea. These certificates were not common and were given out specifically to 6 Group bomber crews for a direct hit on a target. This attack took place on the night of 6 September 1944 and the certificate includes a post raid reconnaissance photo of the target showing heavy smoke. The Larson crew at this time was comprised of Flying Officer Bud Larson, Sergeant Hobbs (Gunner), Sergeant J. Bolen (Bomb Aimer), Warrant Officer R.B. Van Metre (Wireless Operator), Sergeant Michael Allan Potter (Flight Engineer), Flight Sergeant Little (Navigator), Sergeant Ford (Gunner). Larson has obviously written in by hand their later promotions. The certificate is signed by none other than Air Vice Marshal C.M. “Black Mike” McEwen, Air Officer Commanding, 6 Group, one of the most loved and respected Canadian Bomber Command leaders. Photo: Larson Family

The preceding story called Lifting the Dead was selected not because it was the most hair-raising of Larson’s 52 combat ops (12 regular, 40 Pathfinder), but simply because it underscored the training and decision-making of one of Canada’s top bomber pilots. The loss of an engine on takeoff was not uncommon, expected in fact. The RCAF and its colleague air forces all knew that training and crew selection would go a long way to making this type of event almost routine, though it was far from it. As mentioned, Larson had many more brushes with death, events that were far more traumatic and frightening. On the night of 7–8 March 1945, Bud and his crew had a much more trying time, almost not making it back. Their British tail gunner, R.W. Hainsworth was killed. The gripping account of the night’s terrors can be found in the 405 Squadron Operations Record Book (ORB) for the month of March. By this time, some of his first tour crew had left, but others like Flight Engineer Potter, Bomb Aimer Bolen and Navigator Van Metre were on their second tour with him (usually, Flight Sergeants were given a commission when they signed up for a second tour—hence the difference in their ranks from previous missions). The story is not embellished in any way, yet what follows reads like the script of a movie:

405 Squadron R.C.A.F. Squadron (P.F.F.)

Gransden Lodge, Bedfordshire

Lancaster III “D” MA965 March7/8, 1945

J.85250 F/O Larson L.M. Pilot

144997 F/O Davies H.J. Navigator

J.89496 P/O Bolen J. Bomb Aimer

J.89792 P/O Van Metre R.B. Wireless Op.

1550817 W/O Webb H. Mid-upper Gunner

1321081 W/O R.W. Hainsworth DFM Rear Gunner

[Of the crew, Larson, Bolen and Van Metre were Canadians, the others RAF]

Time up 1744, Time down 0250, Total Hours 9.06

Bombing attack on “Dessau”

“D” BLIND SKY MARKER: – 8 to 10/10th’s cloud at 5 to 6,000 feet with good visibility. Bombed target at 2200 hours from 18,000 feet on airfield just West of target. Arrived at target early and marking was obscured by cloud. At 2200 hours saw airfield through break in cloud and bombed this. No results seen.

At approximately 2200 to 2205 hours, whilst over the target area, and immediately after the bombs had been dropped, we were attacked by three enemy aircraft. The first attacking aircraft was shot down by the rear gunner on its first attack. The second enemy aircraft fired a burst which caught the rear turret, setting it afire, and injuring the rear gunner [Hainsworth]. As this enemy aircraft turned away from the bomber, the mid-upper gunner [Webb] fired a burst and the enemy aircraft was seen to burst into flames and disappear.

The wireless operator [Van Metre] forced his way into the rear turret and saw the rear gunner slumped in a position half in and half out of the turret. The fire was raging fiercely at this time and part of the rear gunner’s parachute was on fire. The wireless operator tried to pull the rear gunner to a safe position, but without success. His only alternative was to help the rear gunner out of the side of the turret. It was presumed by the wireless operator that the rear gunner was dead while this was happening. Had the wireless operator been successful in pulling the rear gunner to a safe position in the aircraft, it would have endangered the whole aircraft, since the fire was getting out of control. Whilst all this was going on, the third enemy aircraft was strafing the bomber. The pilot of the aircraft [Larson] was successful in bringing the aircraft back to base on three engines, although the aircraft was severely damaged.

In a 2011 interview with writer Trish Bartlett for his Creston Valley, BC community magazine, I Love Creston, Bud filled in some of the details of getting that aircraft home, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross:

“I tried a corkscrew manoeuvre through the clouds to lose him but each time he found us again because of the flames from the tail. I finally lost him when the fire burnt out.”

They’d been gone longer than usual and he wasn’t sure if they had enough fuel to make it back.

“At one point I wanted to tell the crew to bail out,” Bud says, “but I couldn’t since the intercoms were down. So we just kept flying and we made it back to our airfield. Three engines don’t use as much fuel as four.” Bud was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for that mission.

“They gave us a week to recover, but eventually we had to return and start flying again,” he says. “We were a scared bunch of fellows the first few trips but we didn’t have many left before the end of the war.”

The Two Tour Pathfinder Hero Returns to Canada

Larson was correct... there were not many more operations left before the end of the war, but even if there was only one, your number could be up. Luckily, he lived to make a return to Canada, flying one of the 405 Lancasters back across the Atlantic to Scoudouc, New Brunswick to become part of Tiger Force—the RCAF Lancasters fitted out for a continuing war against Japan. Fortunately for Larson, the war against Japan ended before he was drawn into it.

After a month’s leave in Canada, Bud was asked if he wanted to be part of a touring air show, flying a Lancaster around Canada for display to the public. It was set up to raise money for the RCAF Benevolent Fund to assist injured veterans. “It was a wonderful experience talking to all the people about what we had done during the war,” said Larson. “A lot of people didn’t know. We visited Vancouver, Lethbridge and Calgary and were on this trip for a month.” In the process of touring a Lancaster across the country, Larson and hand-picked crew set a long distance speed record in the Lancaster. The crew, led by Bud, flew from Vancouver to Winnipeg in 4 hours and 47 minutes.

In a photo taken in Regina, Saskatchewan on Larson’s cross-Canada promotional tour with another Lancaster crew, he poses in front of the port main gear and No. 2 Engine. The Lancaster in this photograph however does not appear to be the same aircraft (FM122, LQ-L) which he and his crew flew during their tour. Looking at this face, it is hard to believe he is just 25 years old in this photo—a year and two tours of Bomber Command Operations lines his face. Photo: Larson Family

A close-up of Bud Larson’s tunic from the previous photograph reveals some decorations any man would be extremely proud of—earned by flying through some perilous “adversity to the stars.” At the bottom is the RCAF Operational Tour Wings given to aircrew who have completed a full operational tour. The chances of surviving a full Bomber Command combat tour of 30 ops were, at one time, down to 16%. Above his pocket button he wears his Pathfinders Force Badge, demonstrating his above average skills as a pilot and a combat crew commander. His ribbons include a Distinguished Flying Cross (diagonal purple and white striped ribbon) at left. Above that, perhaps his proudest—the wings of a Royal Canadian Air Force Lancaster pilot. What is not shown here is the “bar” to his Operational Tour Wings. After the war, Bud was awarded a certificate from the RCAF which gave him a bar to hang from the bottom of his Wings, meaning he successfully completed two tours with Bomber Command. Photo: Larson Family

A full-page ad appeared in the Monday, 13 August 1945 edition of the Regina Leader-Post advertising an air show the following day, starting at 1400 hrs and running, oddly, until midnight. The show promised Action! Drama! Explosives! For a boy who grew up not far from Regina, this was a powerful and emotional homecoming. Just the week before, the Americans had dropped two atomic bombs on Japan—on Hiroshima on the previous Monday and on Nagasaki the following Thursday. This ad appeared on the 13th, the air show was on the 14th and on the 15th, Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s voice was heard by Japanese citizens for the first time on radio—urging the nation to lay down their arms. The 15th was VJ-Day. Scan: Regina Leader-Post

They say any press is good press anytime they spell your name right. Larson’s press was all good despite having his named spelled incorrectly in this Winnipeg newspaper story about the Victoria to Winnipeg dash which won them a speed record. Judging by their DFCs and ranks, these men were hand-picked for the public relations tour, possibly a reward for exceptional service. A quick scan of this newspaper clipping reveals that everyone of these men is wearing either a Pathfinder badge or Operation Tour Wings or in the case of most, both. The crew is comprised of co-pilot Flight Lieutenant Jim Hartley, DFC of St Catherines, Ontario; navigator Squadron Leader Jack Roberts, DFC of Toronto; rear gunner Warrant Officer Thorburn Christie, DFM of Ottawa; wireless operator Flying Officer Roy Van Metre DFC of Calgary, Ontario; mid-upper gunner Flying Officer “Pop” Tennyson of Timmins, Ontario; navigator Flight Lieutenant Bill Fraser of Flin Flon, Manitoba and pilot and commander Bud Larson, DFC of Regina. The joy and pride on their faces is a thing of beauty. Clipping: Larson family

Flight Lieutenant Bud Larson, DFC (right) and two of his record setting crew (Flying Officer Roy Van Metre, Radio Operator (beside Bud) of Calgary and Flying Officer “Pop” Tennyson, the Mid-upper gunner). Of the group flying across the country on a public relations tour, only Van Metre was a member of his wartime combat tour. Photo: Larson Family

The hero returns to Regina, Saskatchewan during Larson’s tour of Canada in the Lancaster. One might expect to run into some pretty girls doing a cross-country, public relations tour in a big impressive airplane. Pictured on the ramp, in front of what is now the Regina Flying Club, are Bud’s future wife Edna (left) and Bill Fraser’s wife. Flight Lieutenant Bill Fraser, of remote Flin Flon, Manitoba, was the navigator in Larson’s crew for the victory lap across Canada. Photo: Larson Family

Following his cross-Canada tour and the full end to the Second World War, Bud Larson quietly put away his decorations and his beloved RCAF uniform and returned to the tiny town of Cabri, Saskatchewan to pick up the threads of a life he had put on hold. As he readjusted to civilian life, the deeply experienced multi-engine pilot had hoped to continue to fly. His hope was that some of the bombers would be converted to commercial transport use and he could continue to fly, but it was not to be. Commercial aviation was highly competitive and not expanding as he had hoped. He took an accounting job with the Municipality of Cabri, then eventually a similar position in the larger town of Davidson, Saskatchewan. He is now retired in Creston, British Columbia. He never flew an aircraft in command for the rest of his life.

Heroics and greatness are an everyday component of Bomber Command operations, but these men never ceased to be great or to be heroes when they returned. These attributes took the form of good citizenship, strong values, strong work ethic, a good father and husband, and above all pride in his country. He voted, participated in and worked hard for his community, remained fiercely loyal to friends, suffered no fools, expected the same from the next generations and took part in the growth and simplicity of his country, which he risked so much for. Which so many of his friends died for.

Bud Larson was the kind of man Hollywood made movies around—a cross between Robert Mitchum and Gary Cooper. His service is a saga of heroics, professionalism, sacrifices, triumphs, divine intervention and accomplishment. But you would never know it standing behind him in the check-out line.

And that’s the way Bud would like it.

Last summer (2014) Flight Lieutenant Bud Larson was invited to handle the throttles of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada’s Lancaster during a four engine run-up. Here we see him reflecting on his formative, terrifying and life changing career as a Bomber Command Pathfinder pilot, feeling the vibration coming through his hands and seat one more time. This time, all four engines were running nicely. Photo: Larson Family

In his 90s, Larson still looks every bit a warrior and someone you don’t mess with. Photo: Larson Family

A happy Flight Lieutenant Bud Larson poses in front of a Lancaster nose section on display at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta in the summer of 2014. Photo: Larson Family

Flight Lieutenant Lyle Erling Larson, along with members of his family, poses with his sister Isabel, in front of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada’s Lancaster during a visit in the summer of 2014. Photo: Larson Family

When Bud Larson paid a visit to Nanton to sit in the cockpit of the Lanc and to feel the power of her four Merlins in his hand once more, the author had the honour of doing a flypast in his honour in his vintage T-28 Trojan.

About Todd Lemieux

Todd Lemieux grew up on the family farm near Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan and learned to fly when he was 16 years old via the Royal Canadian Air Cadet program. He obtained his glider pilot license in 1985, followed by his private pilot license and glider instructor rating. A professional engineer for the past 20 years, it was in the oil and gas industry that Todd worked with Mr. Barry Larson, a geologist, and over beers (naturally) decided to co-author a story on Barry’s uncle, Bud Larson. Todd now spends his time between Calgary, Alberta and “The Ranch” in Nanton, Alberta. He is an enthusiastic warbird and formation pilot, operating a Citabria and T-28 Trojan. The former Chairman of Vintage Wings of Canada now spends his time volunteering with the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, consulting and flying warbirds.

About Piotr Forkasiewicz

Polish digital artist Piotr Forkasiewicz composed the amazing “head on” shot of Bud’s airplane jettisoning it’s bomb load in the North Sea. His works, almost voyeuristic in detail and immediacy, grip the viewer with overwhelming feelings—feelings that portend doom, surreality that creeps up the back of your neck, relief that floods like a warm sunset, spirituality that opens your mind to the immensity of experience that was the inheritance of the airmen of Bomber Command in the Second World War.