NAVY BLUE FIGHTER PILOT — Episode Three

In the third and final episode of Navy Blue Fighter Pilot, Lieutenant Don Sheppard is now a blooded veteran, a respected and much-loved member of 1836 Squadron since his training in Brunswick, Maine. While this was only 18 months previous, it seems like a lifetime to the weary fighter and bomber pilots of HMS Victorious. By now, having been on operations in the icy Northern seas and the heavy heat of the Indian Ocean, Sheppard is used to the dangers, deprivations and miseries of the life of a carrier pilot, but nothing can prepare him for the Divine Wind—the terror of the kamikaze.

Episode Three: Until the Bitter End

Part Four

There is a vast literature associated with the British Pacific Fleet’s participation in Operation ICEBERG, the grueling two-month campaign off Okinawa in the spring of 1945. Although generally of high quality and interest, much of it deals with subjects of little immediate concern to the pilots, observers and air gunners who flew the actual missions. Unlike the British Prime Minister, other politicians and senior navy brass, aviators did not particularly care where they fought in the Pacific, and, with the European war coming to an end, many would have been willing to give it a pass altogether. Also, since most of the aircrew were volunteer reservists—and many of them not British—they were not overly concerned with the desire of some senior officers to prove they could match the capability of the United States Navy’s fast carrier force in order to enhance the Royal Navy’s standing in the postwar world.[1] And they really didn’t much care at all what the cantankerous American Admiral Ernest King thought of the BPF encroaching on his perceived turf—one British aviator passed him off as “a rather snooty chap”, but his view was likely coloured by knowledge accrued after the war.[2] Some aspects of the well-chronicled logistical shortcomings that confronted the BPF did impact aircrew, especially the poor food and lack of spare aircraft and parts (and sunglasses as we saw in Episode 2), but for the most part these, too, were of limited consequence to those at the sharp end—for example, the fleet’s replenishment problems only served to give aircrew more welcome breaks from operations. It is not meant to be dismissive of these important issues or the historians who have studied them so well and so thoroughly; rather to emphasize that they were not of real consequence to the aviators who faced deadly flak on an almost daily basis, suffered through dreadful conditions on board their carriers, and endured exposure to kamikaze attack, a new and frightening form of warfare. Fortunately, the voluminous operational records available from ICEBERG enables one to get at the aircrew experience, and to follow the ordeal—for that is the word—of aviators like Don Sheppard through ICEBERG on a mission by mission basis. Some may consider such a narrative mundane and repetitive, but that was precisely how the campaign came to be viewed by those directly involved, though with intermittent bouts of fear and trepidation mixed with questions over its broader consequence.

Don Sheppard and his fellow aviators in HMS Victorious reflected on little of this as they made their way toward Australia in January 1945 after wrapping up Operation MERIDIAN. Instead, their minds danced with thoughts of rest and recreation. After a brief layover at Freemantle and passage to Sydney, Sheppard and the other Corsair pilots eventually flew down to the naval air station at Nowra, south of bustling Sydney and not far from the picturesque white sand beaches at Jervis Bay. He flew a few training sorties to keep his hand in but spent most of the time relaxing. Lieutenant Robert H. ‘Hammy’ Gray, RCNVR, senior pilot with Formidable’s 1841 Squadron, described his own carefree experience in Australia in a letter home:

Now I am able to tell you about Sydney—Well it is a wonderful place indeed. There is no doubt that it is the most hospitable place of its size I have ever been to. We have a large number of ratings aboard and I do not think there is any of them which did not enjoy their stay here. The ratings who usually find very little to do in a strange port were given a full welcome and as far as I can see they nearly all got some home life with Australian families, which is something they do not usually get. I myself of course had a good time. I went with my CO and stayed with some people who gave us a very full welcome indeed and showed us everything. The swimming was by far the best I ever had and now I have a very beautiful tan.[3]

Don Sheppard recalled “a very good shore leave”, the highlight of which was meeting up with his older brother Bob, who had also volunteered for the Fleet Air Arm and was flying Corsairs with 1845 Squadron in Formidable. The two brothers had a great chance to catch up but, sadly, it was their final meeting. On 22 March 1945, when Victorious was staging for ICEBERG at Ulithi and Formidable was working up off Australia, Bob Sheppard died in a flying accident. According to witnesses his Corsair appeared to clip a small protrusion at the forward edge of Formidable’s flight deck during a routine launch, stalled, and plummeted into the sea. Strangely, a month passed before Don Sheppard learned of his brother’s fate.[4]

A strike of Corsairs and Avengers powers up in the seconds before launch during the early stages of ICEBERG. The absence of squadron markings on the landing-gear flaps of the foremost Corsair may indicate that it’s Ronnie Hay’s fighter. Note the deck-handlers at the chocks of each aircraft, working amidst a whirling forest of danger. Photo: Sheppard papers

A Corsair Mk II of 1836 Squadron in the spring of 1945. BPF aircraft adopted the blue and white roundel and American-styled “rectangular panels” heading into Operation ICEBERG to approximate USN markings. The letter ‘P’ on the tail signifies the Corsair belongs to Victorious; the figure ‘I’ is the designated “unit number”; and ‘20’ is the “terminal number” assigned by the squadron CO; all were painted in sky blue—this pattern was laid down by Admiralty regulations and was changed in the last months of the war. Sub-Lieutenant Don ‘Whitey’ McNicol, RCNVR, who joined 1834 in May 1945, flew JT-633 on several missions over Japan and referred to it as his private ‘cab’. The lady on the cowling is unidentified. Photo: Randy and Jane Hillier

Victorious departed the friendly confines of Australia with the rest of the BPF on 28 February 1945. Operational flying began immediately with the carriers rotating CAPs and anti-submarine patrols. Sheppard had a close call the first day out when he had to make an emergency landing after his Corsair suffered a complete hydraulic failure—he had to manually pump down his flaps and landing gear. On 12 March came the good news that he had been awarded the DSC, undoubtedly cause for celebration in the wardroom. This came on the heels of news the previous month that he been promoted to Acting Lieutenant. That, in combination with his now considerable experience and obvious skill, elevated him to more responsible positions within 1836 Squadron, and he now flew at the head of a flight or section.

On 13 March 1945, Indomitable (flag), Illustrious, Indefatigable and Victorious put into the large American fleet anchorage at Manus in the Admiralty Islands. There they sat for six excruciating days, roasting uncomfortably in the brutal tropical heat and humidity, while senior Allied leaders on the other side of the world wrestled with the decision of whether the BPF would support Admiral Chester Nimitz’s attack on Okinawa, join General Douglas MacArthur’s offensive in the Southwest Pacific or be reserved for Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten’s proposed amphibious operations in the Indian Ocean. The tug of war finally ended on 14 March 1945 when the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who exercised strategic direction over the war effort, endorsed Nimitz’s plan. Their fate finally settled, on 18 March the BPF carrier force, now designated Task Force 57, weighed anchor for the USN’s advance base at Ulithi in the Caroline Islands to join Admiral Raymond Spruance’s US 5th Fleet for Operation ICEBERG.[5]

Related Stories

Click on image

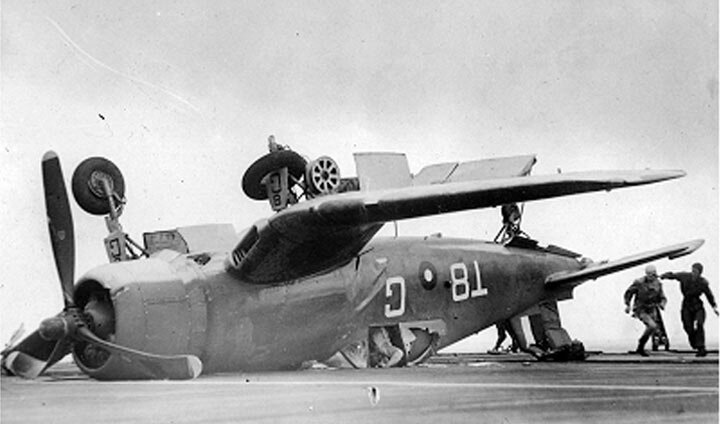

Things happened extremely quickly during a deck landing, particularly when landing a high-performance Corsair on a smaller escort carrier. No more than one or two seconds would have elapsed from the time this Corsair from 1836 Squadron missed the arrester wire until it settled on its back after crashing into the barrier. One can only guess what the pilot might be thinking as his aircraft tumbled over, but he would have been powerless to save the situation. Judging from the damage, he came down hard on his port landing gear, which snapped. The incident occurred in February 1945 on the escort carrier HMS Striker off Jervis Bay, Australia when replacement pilots for 1836 were conducting Deck Landing Training. During ICEBERG, Striker and other escort carriers ferried replacement aircraft to TF-57. Photo: Imperial War Museum

TF-57’s mission seemed relatively straightforward. According to their tasking order, “The object set the British Task Force in ‘ICEBERG’ was the neutralization of the Nansei Shoto Group of Airfields; that is, to deny these airfields to enemy aircraft who might be staged through from China and Formosa to attack Okinawa Invasion Forces.”[6] The airfields were located on an island group known as the Sakishima Gunto, which lay where the East China and Philippine seas met between Formosa and the site of the American landings on Okinawa. The position of the islands gives some idea of their strategic value: Okinawa lay some 150 nautical miles to the northeast, Formosa about the same distance to the west, while Kyushu, in southern Japan, was about 900 nautical miles to the northeast. By neutralizing the airfields, TF-57 would protect the left flank of the massive American amphibious force supporting the invasion of Okinawa. As with the BPF’s earlier operations in the Indian Ocean, Admiral Fraser elected to command his fleet from ashore so at sea TF-57 was under Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Rawlings, but he relinquished control to Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian, Flag Officer 1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron or ‘AC 1’, when flight operations were under way. Vian had five fleet carriers to work with over the course of ICEBERG:

When TF-57 withdrew on its replenish cycles, the USN task unit TU-52.1.3 with four escort carriers equipped with Avengers and Hellcats fulfilled the mission.

Avengers over TF-57 during Operation ICEBERG. The image shows the vast area occupied by a fleet at sea. Despite the fact that TF-57 and the USN forces off Okinawa lingered in the same area for weeks, the Imperial Japanese Navy failed to use submarines against them. Any sustained success by submarines would probably have had a significant impact on Allied deployment patterns, particularly TF-57’s. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Vian and his staff had only a matter of days to absorb the massive pile of operation orders and intelligence material provided at the last minute by the USN. According to intelligence, Japanese installations in the Sakishima Gunto included “seven airfields, 1 reported but unconfirmed seaplane base, a possible minor naval base, and a guard force headquarters.” Six of the airfields were on the two main islands of Miyako and Ishigaki with another on the smaller Iriomote. They varied in size and defences but Hirara airfield on Miyako, which Sheppard was to attack a number of times, can be seen as typical. It had three coral-surfaced intersecting runways, about 17,000 feet of taxiways and 38 revetments to protect aircraft. Although there were no hangars, it had a control tower and seven machine shops. Most of the airfields featured substantial anti-aircraft defences, and Hirara boasted 9 heavy AA positions, 38 light positions and 12 machine guns; another 8 heavy and 68 light flak emplacements were empty but ready for use. In terms of air strength, the Formosa-Nansei Shoto area was thought to be home to about 100 fighters, 80 bombers, five flying boats and 95 reconnaissance aircraft. Surface units of the Japanese navy were not thought to be a threat, but intelligence officers estimated that 25–30 fleet submarines and a number of midget submarines could be deployed into the areas where the USN task groups and the BPF would operate. Attack from “rocket boats and one-man suicide motor boats” could also be expected.[8]

TF-57 pounds Hirara airfield on Miyako early in ICEBERG. Miyako, which Sheppard attacked a number of times, was a tough nut to crack, initially defended by an estimated nine heavy AA positions, 38 light positions and 12 machine guns. The relatively flat rolling terrain did not help. The light colour of the runways is derived from the coral used in their construction, which also made them relatively hard to damage and easy to repair. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

To fulfill the objective of neutralizing the airfields Vian and his staff prepared a complex strike plan that would keep a maximum sustained effort over the target area utilizing aircraft from each carrier. For Day One, Vian laid out the following missions:

· Strike ABLE: At H-hour, a fighter sweep of 48 Hellcats and Corsairs

· Strike BAKER: At H+2.45 a strike by 24 Avengers, escorted by 24 Corsairs and 4 Fireflies

· Strike CHARLIE: At H+5.45 a “similar” strike to above

· Strike DOG: At H+8.45 a fighter bomber strike of 24 fighters and 4 Fireflies

The Group, Strike and Escort Leaders were specified as were the armament loads for all aircraft. Each aircraft carrier’s Avengers were given precise targets to attack at the various airfields; for example Victorious’ 849 Squadron had “Airfield Installations” as their primary target, with “Dispersed Aircraft” as their secondary, while Illustrious’ 854 had “Dispersed Aircraft” and “Runways”, respectively. The primary objective of fighter sweeps was “the destruction of enemy aircraft both in the air and on the ground, and the attainment of air superiority. Other targets should only be strafed if they will have an immediate effect on the success of the mission or if their destruction will have an immediate and substantive effect on the capacity of the airfield to operate aircraft.” After conducting their sweeps, fighters would maintain a standing CAP over the airfields—what became known as the Island CAP—to the limit of their endurance. Although the strike plan evolved over the course of ICEBERG and the order and nature of the missions changed from day-to-day depending on the weather, damage assessments and enemy activity—on some days, for example, a fifth strike, dubbed EASY, was flown—one can readily appreciate the sophistication of the planning, which reflected the BPF’s ability to apply lessons from previous operations.[9]

Besides the invaluable intelligence shared by the USN, Sheppard and his fellow pilots also benefitted from the Americans’ vast tactical experience. In the same way that Lieutenant-Commander Donald Gibson had provided guidance based on his war experience at the RN Fighter School in Miami (see “Navy Blue Fighter Pilot Episode 2”). A confidential publication from TG-58, the fast carrier group, titled “Carrier Action Notes”, presented ‘bumpf’ on myriad subjects of use to pilots, including tactics, mission summaries, and equipment and ordnance—the authors’ claim, “Look it’s all in here” is bang-on.[10] A second document was, perhaps, even more valuable, since it was an updated copy of the personal exhortation Rear-Admiral Marc Mitscher, USN, the commander of TG-58 and a doyen of modern carrier operations, gave his pilots prior to their massive strikes on Japan in February 1945. Highlighting their superior skill and calculated to boost confidence, it was a list of ‘do’s and don’ts’ expressed in pilot lingo—for the FAA aviators, it was as if Mitscher was speaking directly to them. “It is a proven fact”, Mitscher encouraged, “that our VF [fighter squadrons] working together can handle four times as many Japs”:

In a general melee this is only possible if our fighters stay in the same general air space, shooting Japs off each other’s tails, with sections invariably in formation throughout. The Japs will scatter but don’t dive out after them unless all friendlies go together. Clear the immediate air, rejoin the team, and look for more meat.

With regard to ground attacks, Mitscher advised:

Your strafing should not consist of more than six second bursts maximum. Don’t start strafing until you know you have a target and can hit it. Remember that a well-placed strafe will chew up an aircraft on the ground even if it doesn’t burn.

Do not make repeated strafing runs on the same target without retiring out of range (2,500 yards) of automatic [light] AA. Preferably out of sight.

There was much more sage advice, and Mitscher concluded his original text with “The success of air combat over Tokyo is assured if you remember the fundamentals outlined above. You must remember them if you want to fight again. NEVER LET THE SECTION BREAK DOWN.” In the amended version published after TF-58’s successful romp over Japan, Mitscher added “the effectiveness of these tactics may be found in the total score for three days operations over Tokyo: 564 Jap Planes shot down against a combat loss of 60 carrier planes, this in addition to the extensive damage done on the ground.” The proof was in the pudding. Sheppard’s copy of Mitscher’s memorandum is worn and dog-eared, indicating he gave it repeated attention.[11]

Before delving into Sheppard’s experience in ICEBERG, a final point needs to be emphasized. Typically in carrier warfare, manoeuvrability was the primary asset, with the ability to strike hard at a target and then hit another hundreds of miles away. The USN’s fast carrier forces—the masters of the genre—had provided deadly evidence of this capability in their operations across the Pacific. Off Okinawa and the Sakishima Gunto, however, USN and RN carriers loitered in the same general area for days at a time, almost as if at anchor, launching strike after strike—the only difference was that the USN faced far more severe attacks due to operating within close range of airfields on Kyushu in southern Japan. The experience was thus the maritime equivalent of trench warfare; a desperate, unrelenting war of attrition where little seemed to change. At a briefing during TF-57’s passage to the operating area, Rear-Admiral Vian barked at his squadron leaders to tell their pilots to “GET BLOODY STUCK IN!”[12] That they did.

At 0635 on 26 March 1945, TF-57 began two days of strikes from a launch point about 100 miles south of Sakishima Gunto. Conditions were challenging with high winds and an incessant easterly swell, and as Vian recounted, “it has been necessary to operate aircraft in heavier sea conditions than carriers have been accustomed to.” Nonetheless, attacking according to the plan outlined earlier, the fleet managed 161 strike sorties that inflicted significant damage including 23 enemy aircraft claimed destroyed on the ground at various airfields—as would be the case throughout much of ICEBERG, there was negligible enemy air activity over the islands. In a typical episode, Lieutenant-Commander Tom Harrington, CO of Indomitable’s 1844 Squadron and ABLE Strike Leader, led 16 Hellcats on a sweep over Ishigaki. After launch, he kept his Hellcats down at 500 feet for the first 30 miles to elude Japanese radar, and then climbed to 15,000 feet before letting down to 7,000 feet over his assigned airfields. They remained over the area for one hour and 25 minutes: “8 enemy aircraft were strafed with no good result, damage sustained being one Chicken shot down (pilot recovered by Walrus), 1 Chicken severely damaged (pilot severely wounded), 3 Chickens sustaining moderate to minor damage”—to gain a “good result” was to see a target burst into flames indicating it was a genuine item either loaded with or storing fuel and not a dummy. The badly wounded pilot, Lieutenant Alexander MacRae, RNZNVR, “was hit and severely wounded during his run but continued his attack, eventually returning to base alone in a critical condition; he gave himself a morphine injection in the air and carried out a belly landing on arrival owing to undercarriage system being shot away. This officer conducted himself in a level-headed and collected way, under conditions of severe pain and loss of blood.”[13]

Sheppard’s experience throughout ICEBERG demonstrates the variety of missions pilots typically undertook in such complex operations. For example, he did not get over the islands on Day One, but instead led a flight of four Corsairs on what was known as ‘RAP CAP’. Borrowing a USN tactic, Vice-Admiral Rawlings had deployed the cruiser HMS Argonaut and the destroyer HMS Wager as picket ships about 30 miles in advance of TF-57. The intent was to obtain the earliest possible radar warning of an attack, but also to foil the well-known Japanese tactic of fixing the position of the fleet by having their aircraft follow the returning strike on their homeward flight. Thus, instead of boring holes in the sky over the two ships, Sheppard’s flight acted as ‘delousers’. Strikes returning from the islands were directed to approach the pickets at 5,000 feet in tight formation:

On reaching the picket ship they will orbit, the leader of the formation reporting as he does so. During this orbit the formation will be inspected by the picket ship’s CAP, which will generally consist of four aircraft. Leaders of striking force formations should also assist by taking this opportunity to make a thorough visual search of the surrounding area. One right hand circuit will be flown. …

Any aircraft not carrying out the above procedure, and which approaches the fleet on any other bearing or at any other height will be treated as hostile and will be fired upon until recognised as friendly.[14]

Such closely scripted choreography demonstrates how TF-57’s planners left nothing to chance. Sheppard was up for over four hours on his RAP CAP, but did not sift out any interlopers, and had only one comment after the mission: “Was my back sore!!” Sadly, upon landing he learned that Lieutenant-Commander Chris Tomkinson, 1836 Squadron’s CO, had been lost after strafing Hirara airfield. Hit by flak, he managed to ditch his Corsair offshore and was seen in his Mae West, but by the time the Supermarine Walrus search and rescue (SAR) aircraft reached the scene he was nowhere to be found. Victorious’ CO, Captain Michael Denny, attributed Tomkinson’s death to a faulty life jacket, but his pilots thought he had probably been weakened by the chronic kidney condition that could have got him out of the war (see “Navy Blue Fighter Pilot Episode 2”). Lieutenant James Edmundson took over 1836 Squadron, and immediately voiced criticisms of the SAR organization. Two Walrus were embarked on Victorious but they could not launch until the deck was clear, which took time due to the high frequency of activity on strike days. “No point in having a Walrus with the fleet”, Edmundson complained, “ if it is going to take about two hours to get it airborne after the man has ditched—if it can’t be kept in [immediate] readiness it should be embarked in a cruiser.”[16] Perhaps with the loss of Tomkinson in mind, the SAR organization was later improved.

One of Victorious’ two Supermarine Walrus float planes, which served as TF-57’s search and rescue aircraft during ICEBERG, lands on the carrier. Although ‘Shagbats’ were well-suited to picking-up downed pilots at sea, their slow speed—they cruised at about 95 mph—and the fact that their launch was often hindered by other flight operations, caused delays in responding to emergencies, resulting in the loss of some pilots. Fortunately, USN lifeguard submarines and ‘Dumbo’ aircraft helped fill the gap. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Captain Michael Denny: Victorious’ commanding officer throughout the Don Sheppard’s time in the ship. “A short stocky man with bushy eyebrows, known as a strict disciplinarian”, Denny quickly won the respect and admiration of his sailors and aircrew. Throwing his large carrier around like a destroyer, his coolness and brilliant ship-handling under kamikaze attack in May 1945 helped save Victorious from serious damage. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On Day Two of ICEBERG, Sheppard launched early in the afternoon with Strike CHARLIE. He led two other Corsairs on top cover, and the Avengers included a flight of four from Victorious’ 849 Squadron led by Lieutenant Donald Judd, RNVR. The intent was for each Avenger to attack two different targets depositing two 500-lb bombs on each, but Judd’s strike report describes how dodgy weather frustrated the mission:

The Strike orbited Miyako Jima above the cloud, deployed in line astern and were ordered to drop one bomb on Aukama Airfield. During the long approach dive from the SE – NW slight heavy AA fire from batteries near Nobara and Hirara Airfields was encountered. Bombs were seen to drop on runways, ammunition store, barracks and dispersals. The Strike rendezvoused and climbed to 5,000 feet, but between Tarama Jima and Ishigaki Jima thick storm clouds prevented approach at that height and the Strike turned and let down to 800 feet. A second approach to Ishigaki Jima was made at 800 feet from the East but it was obvious that the weather was too bad over the island and after a search of the coast for shipping, the Strike set course for base. Eight minutes later, on orders from the Strike Leader, the bombers deployed and jettisoned the remaining bomb load in the sea.

The Corsairs and Hellcats went in after the Avengers withdrew, and Sheppard strafed a barracks near Miyara Airfield and aircraft parked on Ishigaki. Two of TF-57’s aircraft were lost in the day’s attacks. Lieutenant Peter Spreckley, RNVR of Victorious’ 1834 Squadron was shot down and killed in the ABLE fighter sweep, and an Avenger from Indomitable’s 857 was damaged by flak during the CHARLIE Strike but the crew was rescued when the pilot managed to ditch alongside the picket destroyer. In addition, six more aircraft were written-off after deck accidents.[17]

A Japanese airfield, probably Nobara, gets pounded by aircraft from TF-57. A number of revetments are apparent to the right of the main runway, and the treed area at the left centre of the image shows how it would be possible for the Japanese to hide their aircraft. Judging from the scores of bomb craters pock-marking the terrain, this image was taken towards the end of ICEBERG, but, again, accentuates the requirement to batter the targets again and again. Photo: Sheppard papers

A Japanese airfield on Sakishima Gunto. Although some bomb damage to the runway can be discerned, the image was probably taken in the early stages of ICEBERG. Since TF-57 had no night flying capability, the Japanese were usually able to repair the runways overnight, forcing aircraft to return to the same targets day-after-day. Photo: Sheppard papers

The original plan called for Task Force 57 to carry out three days of strikes on Sakishima Gunto and then withdraw to replenish. That would put them back on station for 1 April, ‘L-Day’ when the main amphibious assault on Okinawa would occur. However, as so often occurs with naval warfare, weather forced a change. In this instance a typhoon was forecast to hit the refuelling area on the scheduled day, which could delay Task Force 57’s return to operations. Vice-Admiral Rawlings signalled Vian that it was “most important” that they resumed strikes the day before the landings: “I think you have certainly discouraged the use of the airfields for another 48 hours and TF 58 may take up the fray. I do not feel we can guarantee to be back on the important day owing to the uncertainty of the weather in both refuelling areas. I have therefore decided to proceed forthwith to fuel, cancelling today’s strikes.”[18] He took the fleet to Area MIDGE, about 300 miles to the southeast. The replenishment turned out to be a messy affair, conducted in strong winds and choppy seas, and it took Victorious nine nerve-wracking hours to take on 350 gallons of aviation petrol, 623 tons of fuel oil and other materiel. Despite these challenges, Rawlings’ strategy paid off, and TF-57 was back in position to resume strikes early on 31 March.[19]

On his first mission in the new cycle, Sheppard led a section of Corsairs on Rescue CAP, or ‘RCAP’, over the Lifeguard Submarine USS Kingfish, which was positioned off Sakishima Gunto. The USN initiated the Lifeguard Submarine concept in 1943 to help avoid the consequences facing aviators captured by the Japanese, and it had evolved into an elaborate system where boats were pre-positioned off areas targeted for air strikes—the RN had also used submarines in this role during their earlier strikes in the Indian Ocean. It proved immensely successful, and in 1944 the USN’s “Lifeguard League” rescued 117 aviators—beyond those saved, the fact that aircrew knew they had a chance to be rescued boosted morale.[20] During ICEBERG a USN boat was positioned south of Sakishima Gunto during air strikes, and was covered by the RCAP. As with everything associated with ICEBERG, the RCAP was governed by precise orders, spelling out how to defend the submarine from enemy and friendly aircraft—Lifeguard boats were persistently attacked by friendlies—as well as how to assist the boat to locate downed aviators. Beyond having difficulty finding Kingfish, Sheppard’s RCAP went without incident. Earlier in the day, however, a Seafire on RCAP shepherded a damaged Avenger piloted by Lieutenant-Commander Bill Stuart, CO of Indomitable’s 857 squadron, to Kingfish, where he successfully ditched. Interestingly, radio communications between Kingfish and TF-57 aircraft often proved problematic, but in this instance the submarine’s comms were handled by Lieutenant-Commander Fred Nottingham, another Avenger squadron CO, who Kingfish had rescued on 26 March.[21] The fact that two squadron commanders, extremely valuable personnel, had been saved within days spoke to the merit of the Lifeguard organization, and over the course of ICEBERG the rescue subs plucked eleven TF-57 aircrew from the seas off Sakishima Gunto.[22]

The USN submarine USS Bluefish. Along with her sister USS Kingfish, Bluefish served as a lifeboat submarine during ICEBERG, lying close off Sakishima Gunto to pluck aviators who had been forced to ditch. Over the course of ICEBERG the two boats rescued eleven aviators who would otherwise have perished or been taken prisoner. USS Tang, seen in the second image, proved the veracity of the lifeboat concept when she picked up 22 downed airmen while standing by a 1944 raid on Truk atoll in March 1944. Don Sheppard had two encounters with lifeguard submarines, flying an RCAP over Kingfish on 31 March, and startling Bluefish with a low-level pass later in ICEBERG. Photos: navsource.org

While Sheppard covered Kingfish, TF-57 carried out a full day of strikes on Sakishima Gunto. The fleet launched 72 strike sorties, and although they inflicted their usual damage to runways and installations, they claimed no aircraft destroyed or damaged. One Avenger flown by Sub-Lieutenant Reginald Sheard of 849 Squadron was shot down while bombing Ishigaki. The one wrinkle in the day’s operations was that Hellcats from Indomitable’s 1844 Squadron carried out their first attack using rockets—prior to that only the BPF’s Fireflies had used the weapon. Surprisingly, 1844 had no prior training, but Lieutenant Peter Mogridge, RNVR reported, “All the pilots concerned claimed the rockets to be a very excellent weapon although they have never fired them before managed to obtain excellent results.” However, Mogridge discovered “Rockets severely impair the efficiency of the Hellcat as a fighter owing to the preponderance of weight of the rocket installation which reduces the speed by approximately 20-25 knots, and affects the rate of climb badly. There is very little improvement when the rockets have been fired.”[23] In coming missions, TF-57 built on this capability and sometimes used RP Hellcats to mark targets for the Avengers, adding another level of sophistication to the campaign.

The DOG strike on 31 March was led by Lieutenant Ed Jess, RCNVR, an Observer officer from Bedford, Québec, who was CO of 854 Squadron in HMS Illustrious. It was not unusual for Observers to command TBR squadrons, and Jess had taken over 854 after Lieutenant-Commander Mainprice fell victim to the balloon cables over Palembang—Jess was on Mainprice’s wing but, through fortune as much as skill, his pilot avoided the wires. The close call seemed typical for Eddie Jess, who had one of the more interesting wartime careers. In 1942 he completed a tour flying night anti-shipping missions in Fairey Swordfish out of beleaguered Malta, attacking Italian convoys running supplies to North Africa—he and his pilot, Lieutenant Bill Simpson, RCNVR from Kingston, Ontario torpedoed six ships in all. In an unusual move, Jess was then loaned to the RAF’s No. 106 Squadron in Bomber Command, led by the legendary Wing Commander Guy Gibson, and flew a number of missions over Europe in Lancasters—the Admiralty pulled him out when another FAA Observer with the squadron was killed far from the sea over Berlin. Jess then joined 854 Squadron, where he spent the summer of 1944 flying anti-E-boat patrols over the English Channel before heading to the Far East. He survived the war, and intended to join Don Sheppard in the postwar RCN, but was discharged after contracting tuberculosis.[24]

1 April 1945 was ‘L-Day’ for the assault on Okinawa. Four American infantry divisions poured ashore and pushed inland, but despite meeting initial success it would take three months and more than 180,000 soldiers and Marines to quell fierce resistance on the island. All the while, Japanese kamikaze forces carried out a bloody campaign against the some 1,300 USN warships and transports positioned off the island. In all, they sank some 36 Allied warships—26 by suicide attack—and damaged more than 350. Nearly 5,000 sailors perished.[25] Although TF-57 avoided the large, sustained kamikaze attacks launched from southern Japan, the fleet was nonetheless vulnerable to smaller, sporadic raids from Formosa and Sakishima Gunto.

Sheppard narrowly missed TF-57’s initial encounter with suicide aircraft. On 1 April he joined 15 Corsairs from Victorious—designated Squadrons 2 and 3—and Hellcats from Indomitable—Squadron 1—on the early morning fighter sweep over Sakishima Gunto. After they formed up, the fleet’s Fighter Direction Officer (FDO) warned of bogies approaching TF-57. Lieutenant Donald Chute, leading Squadron 3, later reported:

2. The squadrons had reached a height of 15,000 feet heading for the Islands when Limbo called up and gave a vector for bogies heading towards the Fleet. The first height given was 12,000 feet and squadrons remained as they were No. 1 at 15,000 feet, No. 2 at 16,000 feet and No. 3 at 17,000 feet—later 19,000 feet was given as Bogey height and all squadrons climbed, No. 3 to 23,000 feet. The vectors brought the fighters back to the Fleet by a circular course at which point they were ordered to orbit and wait.

3. The bogies were next detected at sea level and No. 1 squadron went down leaving Nos. 2 and 3 at 18,000 feet, at which height they remained, patrolling throughout the engagement.

Nearly invisible amongst a blizzard of spray from flak, a kamikaze attempts to break through to a target in TF-57. This image was likely from the fleet’s initial encounter with suicide aircraft on 1 April 1945. The Japanese varied their tactics during ICEBERG, alternating between plummeting from high altitude or coming in low at sea level. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The bogies turned out to be a clutch of Mitsubishi A6M ‘Zeke’ fighters. The CAP shot down four—three by a Seafire flown by Sub-Lieutenant Richard Reynolds, RNVR[26]—but others made it through to the Fleet, one of which dove into Indefatigable’s flight deck at the base of the island, killing fourteen and wounding fifteen. Presenting the first evidence that the armoured decks of the British carriers could stand up to kamikaze strikes, Indefatigable’s flight deck was out of action for only 37 minutes. Nonetheless, her Seafire CAP diverted to other carriers, and when Sub-Lieutenant Norman Quigley, RNVR landed on Victorious, he missed the arrester wires and crashed into the barriers. He later died of his injuries.[27]

Sheppard, circling at 18,000 feet northwest of the fleet with No. 2 squadron, probably had little awareness of the events unfolding below. When the kamikaze attack ended, the two squadrons of Corsairs were released for their recce. Chute recalled, “No. 2 squadron carried out the recce of Miyako Jima, passed their report to No. 3 squadron and this squadron relayed it to Limbo…. No. 3 squadron carried out the recce of Ishigaki Jima from a low altitude making use of the heavy cloud cover which was down to 1,000 feet, passed the report to No. 2 squadron at 8,000 feet who in turn relayed it to Limbo.” A fighter sweep that afternoon found Japanese aircraft on the ground and appeared to have destroyed at least three. Sub-Lieutenant Harold Roberts from Victorious’ 1834 Squadron was shot down and killed by flak.

Later in the day, Victorious, already scarred by the fatal Seafire crash, endured her first kamikaze assault. Bogies were detected at 1730, and one evaded the CAP in low cloud and came in low at 500 feet. Captain Michael Denny cleared the bridge and coolly watched the aircraft’s approach from the bridge wing. “The fleet was being manoeuvred in a succession of starboard turns during the initial approach of this aircraft”, he recounted:

When it was judged that this aircraft was probably making for Victorious I increased the rate of swing by using more rudder. He approached as for a deck landing for a ‘right hand circuit’. Banking to keep over the deck, he was out-swung by Victorious and his starboard wing touched down on the port flight deck edge at 45 Station, spinning him into the sea. His bomb detonated under water about 80 feet clear abreast No. 8 Station Port. As he was close down over the flight deck the whole way to the point of touching down it appeared as if he was doing his best to turn with the swinging ship but could not make the turn tight enough. The aircraft was believed to be a JILL or ZEKE. The detonation threw tons of water, a quantity of petrol and many fragments of the aircraft on to the flight deck.

The A6M Zeke “suicider” banks in a final desperate attempt to crash into Victorious on 1 April 1945. Denny recalled, “Banking to keep over the deck, he was out-swung by Victorious and his starboard wing touched down on the port flight deck edge at 45 Station, spinning him into the sea. His bomb detonated under water about 80 feet clear abreast No. 8 Station Port.” Testament to Denny’s skill, he succeeded in out-manoeuvring a nimble fighter aircraft with a 30,000 ton, 670-foot aircraft carrier. Photos via ArmouredCarriers.com

Denny’s superb ship-handling kept casualties light, with one rating seriously injured and another slightly wounded. Because Victorious was closed-up at action stations, Sheppard could not access his cabin below the waterline, and probably experienced the attack from the wardroom or one of the ready rooms beneath the island superstructure. His reaction in his log book was perfunctory—“Suicide bomber crashed on port side of flight deck but no damage done”—but there can be little doubt that, along with everyone else, he would have been shaken by the attack.[28] From that day, the kamikaze threat gnawed at the psyche of all personnel, eroding their level of comfort. After the war Sheppard admitted a degree of admiration towards Japanese suicide pilots “for their obvious willingness to die for their country by crashing their aircraft into our ships”, but added, with understated bravado, “I concentrated on doing my best to assist them in their plan to go to Japanese heaven by shooting them down before they attacked our ships.” Some sailors found other practical ways to deal with suicide planes: “Since this incident”, Denny observed, “a number of ratings who normally reside unarmed in flight deck edge pockets, and who had their hair lifted by the close passage of the Suicider, have provided themselves with Bren guns suitably mounted.”[29] Pluck helped.

Sheppard did not fly the next day, after which TF-57 again withdrew to replenish. Back in the operating area on 6 April he flew an eventful CAP mission over the fleet, and the following day flew his first sortie as an Escort Leader. TF-57 launched 78 strike and 112 CAP sorties that day, and Sheppard led the escort for Strike CHARLIE. In that capacity he was responsible for directing the movements of two flights of Corsairs as they covered nine Avengers through their bomb run; once the bombers were clear he directed the follow-up interdiction and recce missions. One Avenger’s bombs hung-up during the initial strike on Hirara airfield, so Sheppard led it to the secondary target Miyako airfield. Unfortunately, Miyako was “Popeye”—clouded-over—so Sheppard guided the Avenger to the rendezvous point, and escorted the strike for the first 30 miles of their homeward journey. Wheeling back to the islands, Sheppard directed the second flight, led by Sub-Lieutenant Alan French, RNZNVR, to patrol over Miyako and photograph a suspected radar station. Meanwhile, he led his flight at low altitude around the town of Ishigaki and Miyara airfield where they shot up a radio station, barracks, revetments and a petrol bowser. Sheppard’s detailed strafing report has survived, and it shows he followed Lieutenant-Commander Gibson’s warning from his training days to stay down on the deck. He carried out the attacks in a 20° to 30° dive at 250 knots through mist and light rain, starting his run at 200 feet and ending up at “zero height”. He opened fire on each target at about 400 yards, and released the ‘tit’ at 100; altogether, his two-to-three second bursts expended only 147 rounds from his six 50 cal. machine guns. After each attack he egressed “low on deck”, and did not return for a second pass. As he finished his last run he happily observed the bowser burning fiercely over his shoulder, signifying it was loaded with fuel the oil-starved Japanese could ill afford to lose. In and out, no fooling around; but some still had not absorbed that lesson. That same day, Lieutenant A.D. ‘Winnie’ Churchill, a seasoned, respected Corsair pilot from New Zealand and a friend of Sheppard’s, was shot down and killed on his third strafing run on an airfield.[30] Sheppard’s mission suffered no losses: fortune played a role but so did sound leadership and tactics.

From then until 23 April, when the fleet withdrew for a major replenishment at Leyte in the Philippines, Sheppard flew nine missions, eight of which were CAPs over the fleet. These proved largely uneventful except for an emergency landing due to a hydraulics failure on 16 April, and the interception of a ‘bogey’ on 21 April that turned out to be a USN PB4Y Privateer SAR aircraft. On 12 April, however, he participated in a strike against an important new target, the large island of Formosa, the site of several major Japanese airfields. Admiral Raymond Spruance, the commander of the US 5th Fleet hovering off Okinawa and Vice-Admiral Rawlings’ immediate superior, was concerned that some of the many suicide attacks on his ships were being staged through Formosa, so he asked TF-57 to carry out two days of attacks that were dubbed ICEBERG OOLONG.

Victorious’ Corsairs forming up for ICEBERG OOLONG in April 1945. Assembling dozens of aircraft of different types from four carriers into an organized strike formation could be tedious business, but had to be carried out quickly and cohesively; and usually with radio silence. FAA leaders utilized a number of tricks to facilitate the manoeuvre: during TUNGSTEN, the formation leader dropped smoke floats to help the fighters gain position, and to help the process along in MERIDIAN squadron and flight commanders identified themselves by lowering their landing gear and tail hooks respectively. Photo: Fleet Air Arm Museum

A beautiful image of a fully-loaded Avenger struggling aloft in the early dawn, probably during ICEBERG OOLONG. With their thoughts and nerves preoccupied with the launch and upcoming mission, the Avenger’s crew likely paid little attention to the spectacular view. Note that the fighters have already launched.

On the first day’s strike, Sheppard flew with Lieutenant-Colonel Hay for the first time since MERIDIAN. Hay and another newly appointed Air-Coordinator, Commander N.S. Luard, RN, had been kept busy throughout ICEBERG, directing strikes and conducting recce flights around the islands.[31] “Filthy” weather, as Hay described, marred the initial strikes against Formosa. Hay accompanied ten of Victorious’ Avengers, led by 849 Squadron’s CO, Lieutenant-Commander David Foster, RNVR, to attack Matsuyama airfield at the northern tip of the island. When they arrived over the target Foster considered the cloud cover too low for bombing so he and Hay agreed he should attack the secondary target, installations around the port of Kiirun. In the post-mission ‘wash-up’ Rear-Admiral Vian’s staff criticized Foster for failing to press on against Matsuyama, but the TBR leader’s defence of his decision was frank, and sound:

There was a ceiling of 4,000 feet around the island, with ground rising to 3,000 feet between the coast and the target area. Avengers are not equipped with bomb sights and unless a thirty degree dive for at least 3,000 feet can be obtained very little accuracy can be expected. As long as I have command of an aircraft, a flight or a squadron of aircraft, I am not going to attack targets under conditions which offer little hope of successful fulfillment.[32]

After the Avengers attacked the harbour, Hay led Sheppard and the other Corsairs on “an impromptu rhubarb”, shooting up Matsuyama airfield, a radio station, factory and railway yards. Other fighters ran into enemy aircraft, including some probably marshalling for an attack on Spruance’s force off Okinawa, and shot down at least 14. Late in the day 1836’s Sub-Lieutenant ‘Dusty’ Rhodes found three Oscars darting amongst the clouds:

Opened fire at 400 yards on No. 1. Strikes on starboard wing. Enemy got into cloud. Second one dove to sea level and I splashed him with 8 seconds burst. No tracer to assist aim in poor light. 3rd was hit with 4 seconds burst and smoked. Got into cloud.

The New Zealander was credited with one killed, one damaged. On the second day of OOLONG Sheppard stayed with the fleet, flying two CAP sorties of four hours, and three hours, twenty-five minutes duration, but he encountered no bogies. Sadly, earlier in the day, Lieutenant Charles Thurston, RCNVR, a Canadian flying Hellcats with 1840 Squadron, fell victim to friendly anti-aircraft fire while defending against an enemy attack on the fleet.[33]

Striding casually up the flight deck of Victorious after a mission—probably Operation OOLONG—pilots of the 47th Naval Fighter Wing exhibit the swagger, smiles and relief that accompanies the completion of a successful operation. Don Sheppard walks third from the right; Barry Hayter third from the left; while James Edmundson shares a laugh with Ronnie Hay at the left of the line. Photo: Tony Holmes and Osprey Publishing

TF-57 returned to its regular duties, but after two more days of strikes against Sakishima Gunto on 21 April the fleet withdrew to Leyte Gulf in the Philippines for a much needed long replenishment period. Worn out, Illustrious and her squadrons headed home to be replaced by Formidable. The other carriers repaired what they could and stocked up on supplies, including new aircraft and replacement pilots. The pause from operations presented senior officers like Vian and Denny an opportunity to reflect upon the progress of ICEBERG. Their analysis covered the gamut of carrier operations but discussion here will concentrate on those aspects that related to Sheppard’s experience. Overall, Vian explained that the TF-57’s loss of 59 aircraft from all causes, against the 33 enemy shot down by fighters, three Kamikazes that “self-destroyed”, and an estimated 97 Japanese aircraft destroyed or damaged on the ground, was an “unrenumerative return.” However, he emphasized, “the operation was one which offered little opportunity of effecting high losses on the enemy.” Vian pointed out there had been little airborne opposition in the target areas and that kamikaze attacks had been carried out by small numbers of aircraft. “On the other hand attacks on airfields and dispersed aircraft are difficult and costly”:

the Management [i.e. the Japanese] of a group of airfields which are daily attacked from dawn to dusk do not display their wares. The bombers are exposed to flak concentrated in the area of attack throughout their bombing runs, whilst RAMROD sweeps are faced with dummy or unserviceable aircraft dispersed in revetments and other conspicuous places in centres of flak, whilst those serviceable are well camouflaged or concealed in woods. The Japanese largely use smokeless, traceless and flashless ammunition; aircraft do not know they are being fired at until they are hit.

It has been a disability that cluster or fragmentation and incendiary bombs have not been available, as these would appear to be the type of missile required to destroy aircraft dispersed in the manner stated.

The situation was not helped by TF-57’s lack of night flying capability, which enabled the Japanese to repair damaged runways and shuffle their aircraft around under the cover of darkness with the result that strike aircraft had to return to the same targets day-after-day. In terms of the aircraft he did have, Vian condemned Seafires for their limited range and fragility, but he praised the American types. The Avengers had suffered high losses but he attributed this “firstly to the determination of their leaders in coming through cloud, which has frequently been at 2,000 feet, to discharge their load, and secondly to the invisibility of the enemy flak.” Though he expressed concern about the all-weather landing capability of Corsairs, he acknowledged “The Corsair Squadrons have done all that was asked of them and more.” Vian was not known to dole out praise freely, but he singled out three of TF-57’s squadron leaders whose performance he considered “outstanding”: Lieutenant-Commander Michael Tritton, RNVR from Illustrious’ 1830, and Lieutenant-Commanders David Foster and Chris Tomkinson of Victorious’ 849 and 1836 Squadrons. The inclusion of the latter two officers speaks to the high standard of leadership Sheppard was exposed to in Victorious.[34]

In his report on TF-57, the USN Liaison Officer attached to the BPF praised Captain Denny’s after action reports as a model for all other carrier COs—be they British or American—to follow, and Victorious’ captain’s report on ICEBERG bears that out.[35] Denny offered that, so far, ICEBERG had “demanded nothing of Victorious that involved undue strain on her capacity.” Yet, he noted “the surviving fit aircrews are all tired, and latterly the quality of their flying had deteriorated, without serious results however, thanks to fine weather and good deck and flying conditions.” In terms of attrition, Denny observed that Victorious had left Ulithi with 43 Corsair pilots fit for flying, and 31 remained, for a “wastage rate” of 30 per cent. The Avengers’ rate was better with 14 crews remaining fit from 17, a wastage of 21 per cent. In terms of aircraft, a total of 67 separate planes had been embarked in Victorious over the course of the operation, and 51 remained operational: “Of the 16 disposed of – 3 were flown off as flyable duds, 3 were seriously damaged before the operation but could not be disembarked at Ulithi due to weather. The remaining 10 were – 9 lost or written off due to enemy action, 1 lost through take-off accident.” Although these loss rates were in accord with previous experience, Denny cautioned that increased activity by the Japanese air force would swell wastage to the point it would cause “anxiety.”[36]

Denny raised two concerns about the conduct of ICEBERG. First, he did not think advantage was being taken of the Corsair’s fighter-bomber capability. He observed that Lieutenant-Commander R.W. Hopkins, RNVR, the leader of 1834 Squadron, “is firmly convinced that his Corsairs unaided could have achieved all that the Task Force Avengers achieved at the enemy airfields. He visualises a multiple series of Fighter Bomber strikes, eight aircraft strong, all undertaken without drop tanks – straight in and out – at the rate of four strikes a day.” Denny admitted, “I am not so sanguine. But there is clearly a future for the Corsair bomber”—he was right and they played a greater role in later operations over Japan. The second matter concerned the CAP. Denny raised the fact that “Victorious appeared to have more than her fair share of High CAPs. This worried the pilots a little, especially as they got the impression they were not getting their full quota of interceptions.” More importantly, he observed that some CAP missions had lasted as long as four hours and 20 minutes—Sheppard’s longest was 4.10, and his average 3.18—and explained his pilots would rather “do a spell in two bites, accepting the resultant doubling of sorties and deck landings.” Vian would never have supported that idea since it meant TF-57 would have to turn more frequently into the wind to launch and recover aircraft, which was already his main cause of complaint with the short-legged Seafires. Denny emphasized that he understood the rationale behind the current CAP procedure, but considered “that there is much weight in the aircrews’ opinions, and that the question has a direct bearing on their ability to stay the course.”[37]

Vian and Denny both kept a close eye on the ability of their aircrew “to stay the course.” Vian had already recommended the Admiralty consider shortening the length of operational tours and improve the flow of replacement pilots to front line squadrons. These issues also caused Denny disquiet, but he was more concerned with the immediate situation, particularly with how the handicaps associated with Leyte would undermine the rest period:

It is feared that the period at LEYTE will not produce all the restoration of stamina and morale that might be expected by the flying world of 6-7 days stand-off, since the ship will be miles from the shore with virtually no boats and living conditions on board, as in all British Fleet Carriers, are pretty grim for the young aircrews still unaccustomed, and imperfectly conditioned, to ship life. There is no need at this stage for them to indulge in a “jelly” or to enjoy the bright lights of a metropolis, but a change of air in a camp or station anywhere on shore would be a valuable restorative.

The vast expanses of the Leyte anchorage made it almost impossible to get sailors ashore at Leyte but Vice-Admiral Rawlings addressed the problem with practicality. “Since the libertymen could not get to the beer, I authorised the beer to be brought to them; this innovation proved immensely popular.”[38]

Images from both ends of the line of TF-57’s carriers at anchor in sweltering Leyte Gulf during their break from ICEBERG in April 1945. Victorious lies in left foreground of the first image. Illustrious has gone home, and been replaced by Formidable. Unicorn was a Repair and Maintenance carrier designed to be able to operate and maintain any aircraft in the FAA inventory. During ICEBERG she largely operated out of Manus, repairing aircraft and ferrying replacements to the fleet, and she joined TF-57 for that purpose during the respite at Leyte. At one point Rear-Admiral Vian recommended utilizing Unicorn as a night carrier so TF-57 could maintain pressure on Sakishima Gunto around the clock, but the measure was never adopted. The images demonstrate the distances and challenges involved in getting thousands or sailors ashore to take advantage of Leyte’s recreational facilities. Photo: Bottom-Sheppard papers, Top-Imperial War Museum

Satisfying thirst for beer did nothing to ameliorate the abysmal living conditions in the carriers. They were simply not designed for sustained operations in equatorial conditions and their crews suffered mightily. Lieutenant-Commander Norman Hanson, CO of 1830 Squadron, described an almost cloistered life onboard a carrier:

There was no escape from it. Your Corsair was in the hangar, one deck up. The flight deck, that torrid arena in the grim game of life and death was two short ladders beyond that. Life was lived, utterly and completely, within a space of about 10,000 yards. Within that area we ate, slept, drank, chatted with our friends, attended church, watched films, took our exercise—and flew, landed or crashed our aircraft.[39]

Corsairs squeezed tightly into Illustrious’ cramped hangar, clearly demonstrating why their wings had to be ‘squared off’ by eight inches. Hangars became almost unbearably hot in the tropics with the flight decks radiating heat and no air conditioning. One can also easily imagine the terrible ramifications if a fire broke out as occurred in Formidable in May 1945. Photo: Fleet Air Arm Museum

The climate of the western Pacific added a whole other level of discomfort. In an article titled “Fighting Japan is Hard Work for British Sailors”, newspaper correspondent Gordon Kingsford-Smith described the dire conditions confronting Victorious’ sailors: “Do you remember the British Sailor you met when the fleet was in Sydney?”, Kingsford-Smith queried his readers; “Maybe you wonder what he is doing now?” He explained that “he has probably not set foot ashore in the three months since the fleet left Sydney.” It was “Stifling hot on board and before long I was dripping with sweat; water was rationed and only at certain times could we even get a drink; the cooling machine was out of action so the water was warm; the little ice available was needed to cool the developer in the photographic section which prints hundreds of prints from our reconnaissance aircraft every day.” When walking through the hangar, “sometimes I trod on sailors sleeping under planes’ wings because it was so hot and crowded below.”[40]

Don Sheppard’s view was no more uplifting. Conditions, he recalled, “were not very pleasant”:

In the fleet carriers the armoured flight deck was hot most of the time and this heat radiated through the ship. The only air-conditioned space I recall was the fighter direction room, and that was only air conditioned to keep the equipment operating, rather than the operators cool. The officers, of course, were better off than the men who had to live and eat in very high temperatures in boiler rooms under tight damage control conditions. We aircrew had the advantage of getting clear of the ship regularly, and it was a real treat to be launched on a combat air patrol for four hours at 20,000 feet where it was nice and cool (and usually quiet).

Beyond heat, humidity and general discomfort, Ronnie Hay found the persistent noise a serious irritant. The carriers manoeuvred at 20–25 knots most of the time they were on station, and Hay recalled the “deafening” engine noise echoing throughout the carrier. Night time was especially bad, with the ship darkened, and scuttles and watertight doors secured—officers like Sheppard sometimes sought relief by sleeping on the open quarterdeck. Hay recalled the entire situation placed an “enormous strain on individuals.”[41] Morale was not helped by the fact that many veteran aircrew rotated home while the carriers were at Leyte, including Sub-Lieutenant Barry Hayter, the other Canadian in 1836 Squadron. The replacement pilots were keen, but their arrival diluted skill and experience throughout the squadrons, putting additional pressure on ‘old hands’ like the 21-year-old Sheppard.

The actor Kenneth More, seen here as Captain Jonathon Shepard in the 1960 movie Sink the Bismarck, did not have to step too far out of character to play a naval officer. The son of a FAA officer, More joined the RNVR in 1941, and served as a Fighter Direction Officer in Victorious during Operation ICEBERG and the later strikes against Japan. FDOs were an integral part of the air team, and Sheppard’s brilliant interception on 4 May 1945, which may well have involved More, demonstrated how the effective use of radar, skillful plotting and the well-honed instincts of a FDO and a fighter pilot could result in success under challenging circumstances. More made other contributions in Victorious: every happy wardroom has a good piano player, and 1836’s Lieutenant Don Chute recalled More’s happy disposition and musical abilities helped boost morale during the rough patches of ICEBERG. Images: 20th Century Fox

So it was a fragile fleet that departed Leyte on 1 May 1945 for ICEBERG II. The first day out Vian ordered a massed “dummy” air attack on the fleet “to exercise the re-formed air squadrons in air drill and combined tactics.” He thought it achieved its object, but it would take longer to assimilate the newcomers: for example, one young Canadian assigned to 1834 was sent back to Australia for more deck-landing training. When TF-57 resumed position off Sakishima Gunto, Vian and Rawlings decided to try a different tactic to help out their aviators, but this one backfired. Concerned with the toll from Japanese anti-aircraft fire, Vian thought a bombardment by the battleships and cruisers might cause heavy casualties amongst enemy flak personnel, “which would be warmly appreciated by our air crews.” Rawlings agreed, but when TF-57 moved into position to launch strikes on the morning of 4 May, several shadowers appeared on radar. The enemy activity stirred doubts about leaving the carriers isolated with less anti-aircraft firepower, and according to Vian, Rawlings

asked me whether I considered that the shadowing of our force indicated that the enemy intended to pay particular attention to us, and implied that if so, he would remain with the battleships and cruisers to lend gun support to the carriers, and would cancel the bombardment. There had been received by that time no indications of an attack of sufficient scale to warrant cancellation, and I replied accordingly.

Vian’s optimism proved to be a miscalculation. When Rawlings’ force moved in to bombard Japanese positions—the 6-inch guns of the recently arrived Canadian cruiser HMCS Uganda joined the shoot—the enemy took advantage and launched a kamikaze attack on the carriers. Formidable was struck by one suicide aircraft, and another glanced off Indomitable’s flight deck. 1836 Squadron’s Sub-Lieutenant Johnny Maybank, sitting in his Corsair at readiness on Victorious when the kamikaze hit Formidable, recalled he had “never seen anything so horrifying.”[42] Formidable suffered eight killed and 47 injured, and although badly damaged, the carrier was able to resume flight operations later in the day. Rawlings has been criticized for leaving the carriers vulnerable but it is clear that he and Vian weighed the situation carefully before acting. That said, perhaps it might have been best to see how the Japanese reacted to the new cycle of operations before splitting the force. As for the effectiveness of the bombardment, Hay was aloft photographing the shoot and thought the results disappointing, observing “The damage done did not appear impressive. There was insufficient accuracy and the salvoes were always just missing.”[43] Nonetheless, the next day TF-57’s strike aircraft encountered less flak than usual over the islands, which was indeed “warmly appreciated.”

The Canadian cruiser HMCS Uganda joined TF-57 for ICEBERG in April 1945. Uganda was a distant cousin to the cruiser HMS Argonaut, over which Sheppard had flown a RAP CAP on 26 March. Uganda also served in the picket role, and took part in the controversial 4 May 1945 bombardment of the airfields on Sakishima Gunto, which suppressed Japanese defences but denuded the carriers of much of their anti-aircraft support—the main role of TF-57’s battleships and cruisers—leaving them open to kamikaze attack. Photo: Imperial War Museum

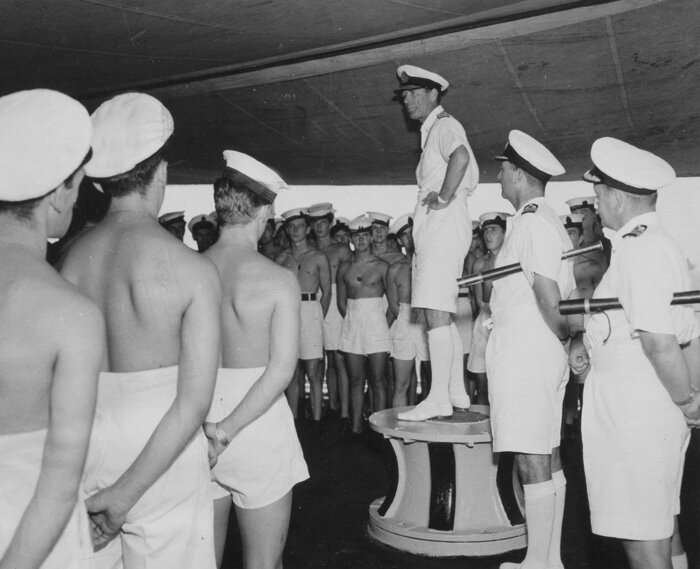

Looking every inch the thrusting fighting hero, Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian welcomes Canadian sailors to TF-57 from atop a capstan on HMCS Uganda’s fo’c’sle. Judging from the seriousness of his countenance, Vian is challenging them “to get bloody stuck in!” The contrast between the rigid formality of the officers brandishing their ceremonial telescopes to the casual stripped-down attire of the sailors due to the oppressive heat is striking. Photo: Department of National Defence

That same day, in an interception that matched brilliant fighter direction with the skills and instinct of a seasoned fighter pilot, Sheppard scored his final victory. Early in the afternoon, Sheppard—designated ‘Loyal 53’—was on deck at the head of three Corsairs, waiting at immediate readiness in case more suicide aircraft approached the fleet:

Before launching, the Fighter Director called me to the Direction Room for a briefing in which he stated that they received a number of strange radar contacts which kept fading and returning. He was not sure if was atmospherics, technical problems or a very high-flying aircraft. Since my flight had not flown that day I persuaded Cdr. (Air) to launch us and let us go up and investigate this strange echo. Fortunately the ship again picked up the target on radar immediately after our launch and held it long enough to give us a good vector and a rough height. We received about three corrections to this vector while in the climb and then the ship lost the target on radar.

Despite the poor quality of the radar return, Victorious’ fighter direction team put Sheppard in the vicinity of target. Visibility was good, with about 3/10ths cloud at 20,000 feet, and as Sheppard climbed through 15,000 feet “by sheer luck I spotted a small dot about five thousand feet above us.” As they continued to climb, the dot grew into an Aichi D4Y Suisei, or ‘Judy’, dive bomber, with “greenish brown camouflage.”[44] Sheppard picks up the hunt in his combat report:

I dropped my tank and gave full boost; climbed up and under enemy aircraft. At 300 yards aircraft started to turn to port, I fired a 1 sec. burst at about 30° and he straightened out and must have dropped his flaps and cut his throttle as I began to gain on him rapidly. I cut my throttle and fishtailed and had time to give him a 2 sec. burst from astern at about 100 yards. He blew up in a terrific flash of flame and at the same time the bombs or drop tanks dropped loose from the wings. The aircraft then descended in pieces and burned on hitting the water. A parachute made free from the aircraft while it descended and was strafed, but there was only the harness attached when I had a closer look.[45]

Sheppard was in too close to avoid the massive fireball, which he thought was sparked by the explosion of a long-range fuel tank in the Judy’s bomb bay. That “made a bit of a mess of my fabric rudder and elevators”, but he was able to land safely on Victorious. Intelligence officers concluded that the Judy was a so-called ‘Gestapo’ aircraft that co-ordinated kamikaze attacks making it an extremely valuable kill, both in terms of the mission that may have been thwarted and the personnel that went down in it. One can also note that Lieutenant-Colonel Hay’s philosophy on how to handle enemy aviators who took to their parachutes had gained acceptance throughout his fighter wing. (see “Navy Blue Fighter Pilot Episode 2”)

“By sheer luck I spotted a small dot about five thousand feet above us.” An Aichi D4Y Suisei or ‘Judy’, dive bomber, with “greenish brown camouflage”, such as Don Sheppard shot down on 4 May 1945. Japanese kamikaze operations were closely directed affairs, and his Judy was likely a ‘Gestapo’ or ‘snooper’ aircraft co-ordinating attacks against TF-57, making it an extremely valuable victory. Photo: NavyField.com

Tallying and classifying aerial victories from a distance can be a mugs game. Standards change over time, and since one cannot go back to sit behind the gun sight to reassess kills, and because records are often vague or nonexistent, evaluations are usually subjective. By the standards of the day Sheppard’s fifth kill made him an ‘ace’, but that status has been the source of some misconception. Some credit him with more victories, others with less, while others choose to ignore his record altogether. Since Don Sheppard is a figure of some historical standing, the discrepancies need to be addressed. First, the total below seems accurate:

4 January 1945: two Oscars

24 January 1945: one Tojo (first claimed as Probable but later assessed as Confirmed)

29 January 1945: one shared Oscar; one shared Tojo (both with Major R.C. Hay)

4 May 1945: one Judy

The categories of “shared” and “probable” victories require clarification. The regulatory ‘bibles’ that governed such matters in the Royal Navy were the Confidential Admiralty Fleet Orders and Admiralty Fleet Orders—CAFOs and AFOs. In the matter of air victories, they imposed rigorous standards. According to CAFO 1021 of 11 May 1944, in force at the time of Sheppard’s victories, “to claim an aircraft destroyed one of the following conditions must have been fulfilled”:

(a) Aircraft seen to crash into the ground or sea.

(b) Aircraft seen to break up in the air or descend vertically in flames.

(c) Aircraft forced to descend and captured.

(d) Wreckage subsequently discovered which established beyond reasonable doubt the identity of the aircraft and that it actually crashed.

(e) In singled-engined aircraft the pilot seen to bale out.

An aircraft counted as “probably destroyed…if it was seen to break off combat in circumstances which lead to the conclusion that it must, beyond reasonable doubt, have ended in categories (a) to (e) above, although not actually seen to have done so.” For the category of “shared” victories, “the destruction should be awarded as shared between two or more pilots if”:

(a) The aircraft would have been assessed as ‘damaged’…before the second pilot attacked.

(b) Two pilots were attacking at the time the aircraft was destroyed, and both can show a reasonable claim to have hit it. (Camera gun evidence is normally required to substantiate the pilots’ claim.)

(c) The destruction of the enemy was the result of team work by two or more aircraft and cannot be fairly attributed to one more than another.

In each ship or station, an officer detailed by the Captain adjudicated all claims to those standards; in Victorious, this was likely the Commander (Air), Commander Sam Little, or an officer on his staff.[47] Sheppard’s ‘probable’ from 24 January 1945 seems to have been assessed as ‘confirmed’ within days of the operation, likely through viewing gun camera film or from discussion with another pilot who had witnessed the combat. And, although some historians have chosen to abandon the practice of totalling shared kills due to legitimate concerns about the accuracy of RAF reporting during the chaotic early months of the war, at the time Sheppard fought, confirming kills was strictly regulated, and totalling ‘halves’ was accepted practice. Therefore his two shared victories with Hay, which would fit categories (b) and (c) above, equal one; thus Sheppard’s total, by the standards imposed by the Royal Navy at the time, was presumably five.[48] Two historians have boosted his score to six, but they mistakenly counted each shared kill as a whole rather than a half. In contrast, the author of a biography of Lieutenant Bill Atkinson, RCNVR, a gifted Canadian naval aviator who flew Hellcats off Indomitable, does not even mention Sheppard’s name, let alone his record, in a detailed but flawed analysis to identify his subject as “Canada’s Top Naval Pilot of WWII”, if any such judgement can indeed be made.[49] This is unfortunate since Atkinson and Sheppard became friends and colleagues in the postwar RCN, and would have found any such discussion distasteful. In the final analysis, whether or not he is considered an ace, Sheppard’s record stands for itself. Importantly, the author can recall no instance where Don Sheppard referred to himself as an ace; not because he harboured doubts about his achievements, but because it was the overall outcome, not the numbers, that counted.[50]

If Sheppard reflected on any of this at the time, it is doubtful it gave him much pause. He flew another CAP mission the next day. Rear-Admiral Vian had hoisted in Captain Denny’s complaints about the length of CAPs and tried to reduce them to about three hours, but circumstances sometimes intervened, and on 5 May Sheppard was airborne for 3 hours and 30 minutes. Two “high snoopers” were detected at midday, but efforts to intercept them failed. Sheppard makes no reference to that in his log book, so it is doubtful he was airborne at the time. That same day, his squadron mates found some trade on the islands. Lieutenant-Commander Edmundson led his flight over the shoreline of Ishigaki “at high speed and low.” They pulled up to 1,000 feet and approached the airfield “from out of the sun and completely unobserved.” Spotting an aircraft being towed down a runway, Edmundson “did a tight turn to port and went in to strafe followed by my No. 2 – the result was most satisfying, as it burst into flames and burnt for 20 minutes. Sub-Lieutenant Rhodes turned to follow me and then saw another single engine aircraft on the taxi track in the NE corner – he strafed this one with exactly similar results.” Although their aircraft strength and aviation infrastructure were taking a beating, the Japanese never ceased their efforts to protect these resources, and Edmundson observed that some runways had been completely repaired and that a new grass field was under construction.[51] There could be no letting up.

Smoke from burning Japanese aircraft obscures Ishigaki airfield during a strike on 5 May 1945. Lieutenant-Commander James Edmundson led that day’s strike on the airfield, and his tactics of coming in low and fast paid dividends as both he and Sub-Lieutenant Dusty Rhodes caught aircraft on the ground. That day Sheppard was flying CAP over TF-57. Photo: Sheppard papers

TF-57 withdrew to replenish so Sheppard did not fly again until 8 May when he conducted a challenging CAP mission in 10/10th cloud. He flew another CAP on the 9th, and although his mission was uneventful, his day was not as Victorious was twice hit by suicide aircraft. Rear-Admiral Vian acknowledged the relative sophistication of the raid, with “high decoys covering a low approach by the Kamikazes, climbing steeply at 20 miles”:

Formidable was hit once, and Victorious twice. A good interception was made on this occasion, but the Seafires who made it were drawn off by one ZEKE, allowing the remainder to come through unmolested. These should have provided good targets for the long range Anti-Aircraft artillery of the Fleet: in fact no useful fire was seen to be opened until the planes were over the screen.

Spectacular images of a kamikaze slamming into Formidable on 4 May 1945. The carrier attempts to evade at full speed under port rudder to no avail. The splashes ahead and abeam of the carrier in the second image are probably the result of shrapnel from the aircraft bouncing off the flight deck. Photo: Randy and Jane Hillier

Firefighters battle the resultant carnage on Formidable’s flight deck. Anxiety clouds the face of the fire ighter approaching the cameraman, while the group at his five-o’clock lead an injured sailor to safety. Despite the havoc, Formidable returned to operational status within hours. In contrast, USN carriers, with wood as opposed to armoured decks, who suffered similar fates, were routinely out of action for weeks or months. Photo: Randy and Jane Hillier

The first kamikaze glanced off Victorious’ flight deck into the main guns, but it dropped a bomb on the way in that damaged the flight deck, and put a 4.5-inch gun, the catapult and the forward lift out of action. The second kamikaze hit a few minutes later, demolishing an anti-aircraft director, damaging an arrestor wire and wiping out four Corsairs in the deck park before bouncing into the sea off the bow. Three were killed and 19 wounded: Lieutenant-Commander Bill Sykes, directing activity on the flight deck, was lucky and just stunned by the blast. Formidable suffered worse damage but the fact that both carriers returned to action in short order—Victorious’ damage control party filled the ‘pot-hole’ in her flight deck with rapid-setting cement—was further testament to the value of armoured flight decks. Formidable was reduced to just four Avengers and eleven Corsairs available for operations, and Vian learned that “Victorious could operate a few aircraft at a time but the damage to her lift seriously reduced her speed of handling them on deck. I therefore recommended a return to the fuelling area for replenishment of aircraft and a return to the strike on the 12th and 13th.”[52]

Long after the war, Sheppard reflected upon the tension impacting personnel “in a prolonged carrier operation.” The nagging anxiety of kamikaze attack probably never dissipated when TF-57 remained in their relatively static positions close to the islands. But Sheppard thought aircrew felt additional strain, “particularly if they don’t have the satisfaction of knowing for sure that the operations they are participating in are really inflicting enough damage on the enemy to warrant the loss of a fairly large number of aircrew to A.A. fire.”[53] This questioning of purpose seems to have gathered momentum through the remaining weeks of May when Victorious’ air group suffered a steady attrition. According to Sub-Lieutenant Ray Richards, a New Zealander who flew Corsairs with 1834 Squadron, Sheppard played a key role in sustaining morale among Victorious’ fighter pilots during this difficult time, using his quiet sense of humour to lift spirits.[54]

The DOG strike on Miyako on 9 May 1945. Lieutenant D.A. Dick of 1834 who led the escort reported “I saw no flak whilst over island. No enemy air activity. All runways on the island appeared unserviceable.” Despite that inactivity that day Victorious was hit by two kamikazes. Photo: Sheppard papers

Victorious on fire forward after the first kamikaze strike on 9 May 1945. The last image shows some of the damage, which, among other things, laid bare her accelerator rail. Three died and nineteen were wounded in the attacks. Photos: Royal Navy