CHUMS

Over the past six years, as part of a personal project, I have mapped, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, the homes of the next-of-kin of nearly 2,000 of Ottawa’s fallen soldiers, airmen and sailors of the wars of the twentieth century. To find them, I have scanned every page of the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Journal from the declaration of each war to the end of demobilization — nearly 250,000 pages— looking for death notices, casualty lists, addresses, stories and photographs. While I most certainly did not ready everything, I learned to scan for relevant stories, lists and photos. l also learned a lot about life as it was seen by Ottawa’s broadsheet newspapers in the first half of the century.

I grew up with the belief that my parents were of a generation steeped in the moral concepts of duty, honour, sacrifice, humility and can-do. In many ways, the Ottawa in which veterans of those wars grew up in was exactly that — an idyllic and timeless environment where family life, commitment and hard work were the pillars of our social structure. In surprising ways it was not.

In the first half of the 20th century, Ottawa’s daily newspapers were peppered with stories you don’t hear much these days — gruesome industrial accidents, quarantinable diseases, railway crossing nightmares, fatal house, hotel and school fires, medical quackery, acceptance of infant mortality and child death, rampant cardiac and stroke plagues, lynchings, brutal union crackdowns — all the horrors of a world before government-regulated health and safety. And there was just as much criminal mayhem then as today — murders, fights, fraud, drunkenness, burglary, exploitation and sexual assault.

Despite the mayhem, however, there was an overall positivity to the news depicted in the broadsheets before television and social media ruined everything. There were still sections dedicated to the goings on of Ottawa’s society, positive stories of young people accomplishing ordinary things but expressed as extraordinary achievements, comics and light humour and local sports. The papers brought news from around the world without trying to spin it left or right. Above all though, local broadsheet newspapers spoke to the community, appraising citizens of the global situation and giving them hope through the achievements of their children, mothers and local service clubs. They brought news of births and deaths with a palpable sense of duty, followed the progress of young citizens with familial-like encouragement and tried hard to colour the world brighter and more hopeful. They were brutally insensitive too — suicides were reported as suicides, mental illness was weakness, homosexuality was indecency, and people of colour were seen through the lens of that colour. We were a monocultured, homogenized society and could never envisage a change in that status.

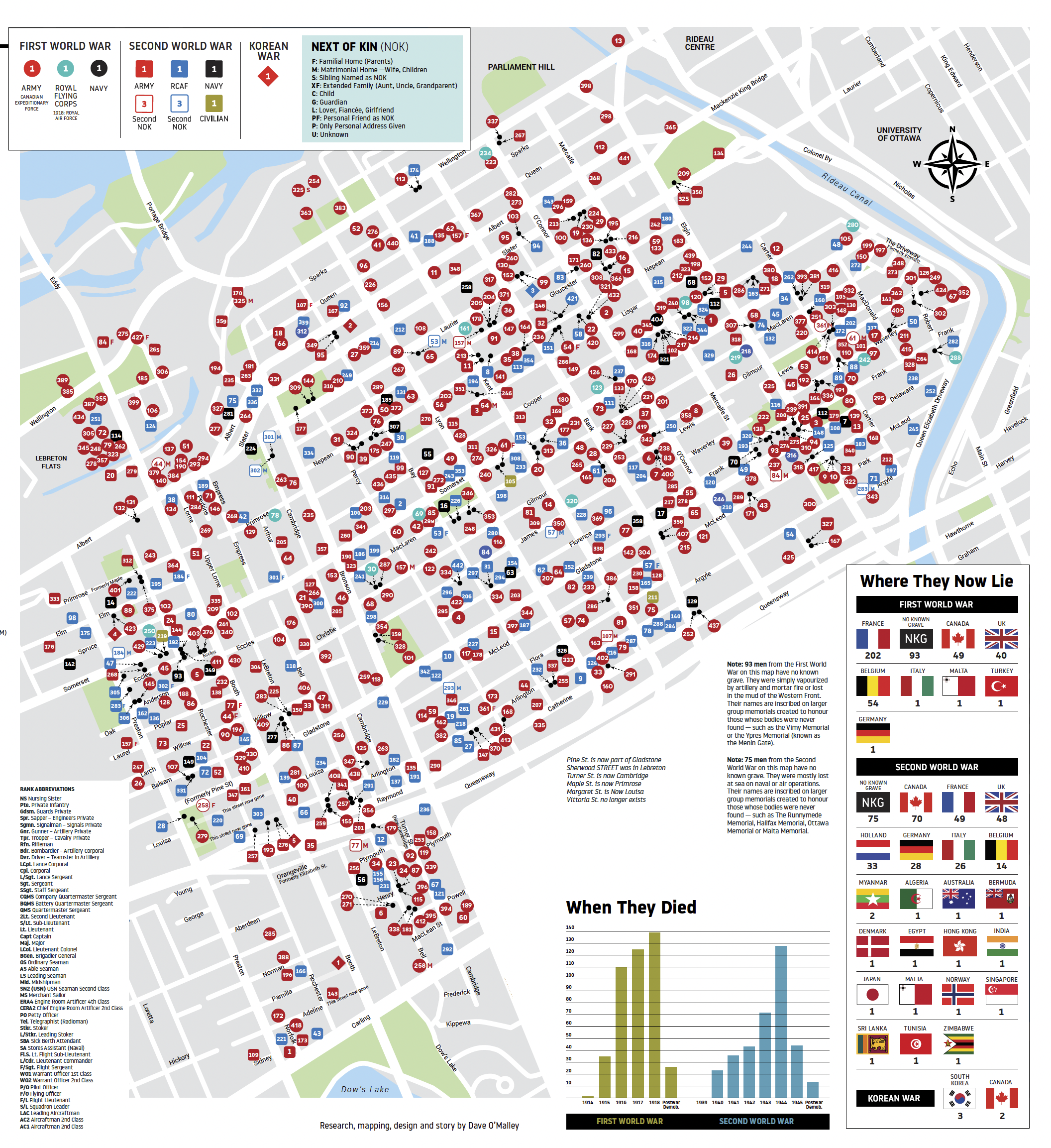

Typical of the maps I created for each neighbourhood, the map of Ottawa’s Centretown depicts the more than 800 men and 2 women from Centretown who died in the wars of the 20th century. I created similar maps and a list for each of Centretown, The Gebe, Sandy Hill, Kitchissippi Ward, Old Ottawa South, Lowertown and Old Ottawa East and published them with a story in each of the community’s newspaper. Map by Dave O’Malley

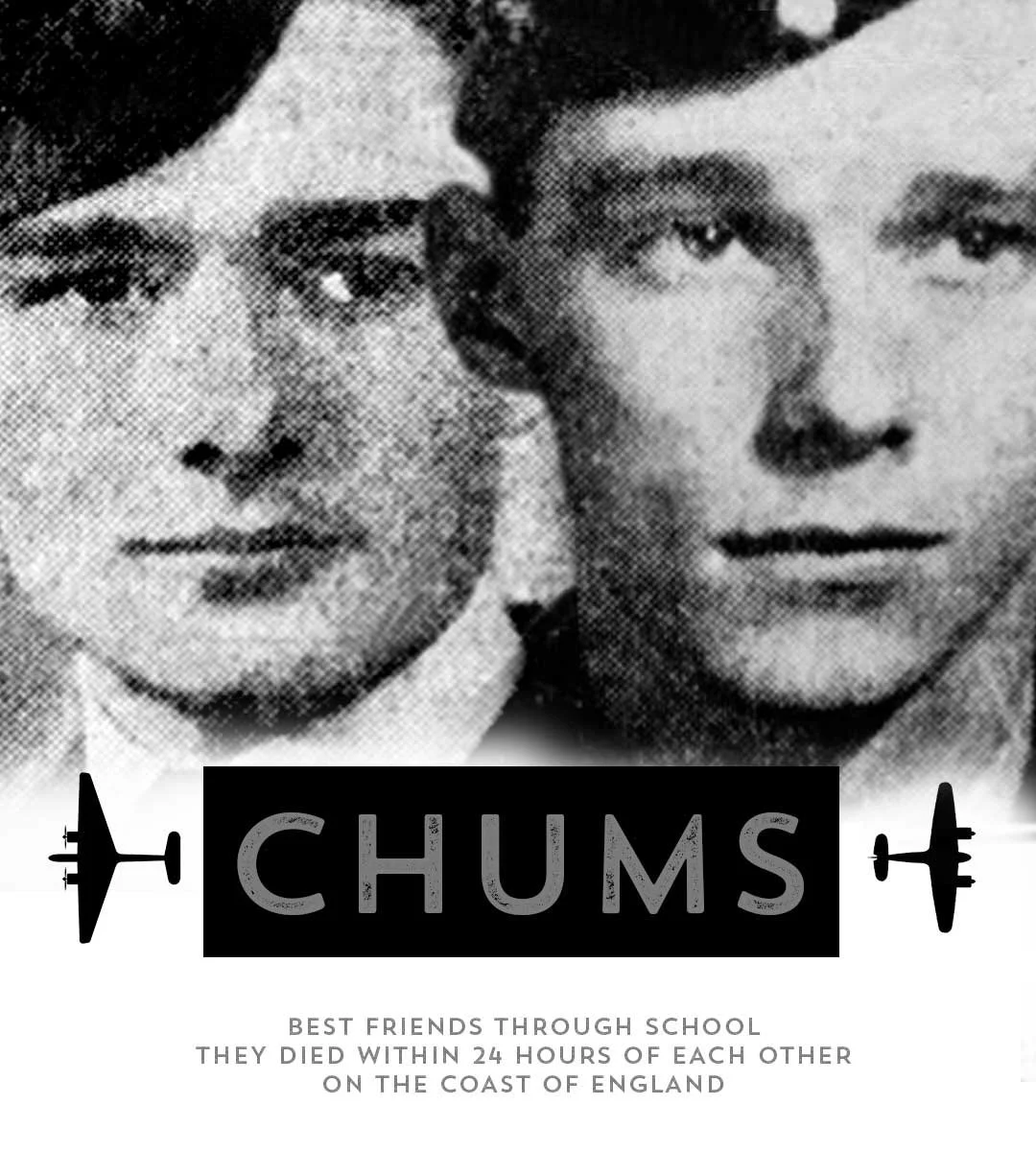

Boyhood Chums

Among the nearly 2,000 men and women I mapped, I found stories that took the grief of their story to another level — men who died on the first day of the war or who died on the last. Men who died on their birthday, on Christmas Day, Mothers Day or Remembrance Day. Men who died on their first bombing mission. Men who died on their last before going home. Men who vanished on their way home. One particular story which appeared in both Ottawa papers in late February of 1943 grabbed me immediately and has held my heart since the day I first saw it.

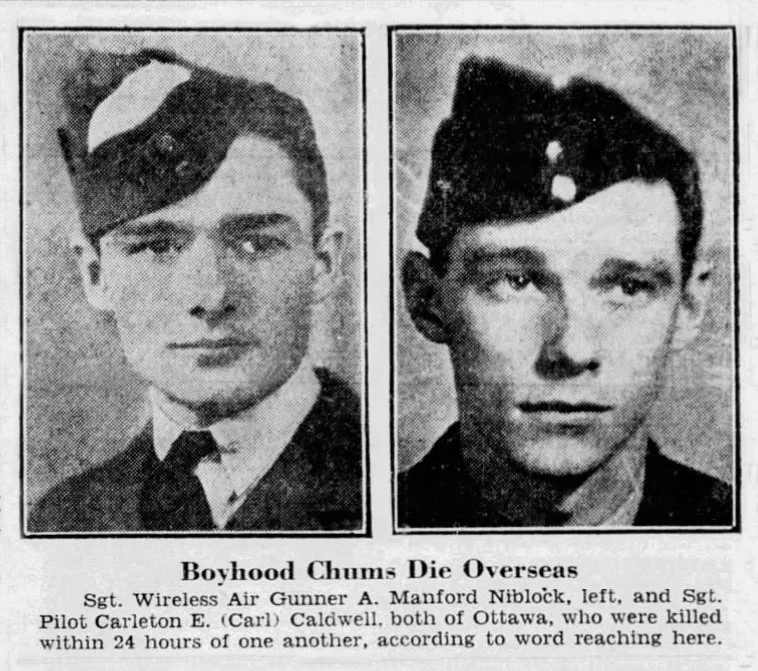

It featured the faces of two young men with haunted looks (to my eyes) on their faces which told a story of both duty and apprehension. It was accompanied by the attention-getting heading: “Boyhood Chums Die Overseas”. These two 20-year old men, both Sergeants in Coastal Command and members of the Royal Canadian Air Force, had grown up together as best friends in what was then the west side of Ottawa. They had spent time together on leave in England and in the end they died less than 24 hours and a little over 100 kilometres apart.

The two men—boys by modern standards—were Sergeant Carleton “Carl” Caldwell, a Bristol Beaufighter pilot within a few weeks of completing his Operational Training at Catfoss and Zina Manford “Manny” Niblock Jr., a wireless operator/air gunner with 415 (Torpedo Bombing) Squadron RCAF. The day I found their story and photos (below) I put them into two folders (one for Niblock and one for Caldwell) for later inclusion in my map of the fallen from the Glebe (they went to Glebe Collegiate Institute) and later a map of Centretown (Caldwell’s family lived on Carling Avenue—PIN number 43 in the map above) and Kitchissippi (where Niblock lived). The file stuck in my brain for several reasons, not the least of which was their haunted unsmiling faces and their sad deaths so close to each other in time and space — a fateful ending to a lifetime of friendship. But, it was Zina Manford Niblock’s unique name and his address on Faraday Street (I had never heard of that street and had to Google Map it) that would soon give their story another level of fate — that very night in fact!

It was this newspaper clipping from the Ottawa Citizen, February 23, 1943, just a few days after their deaths, that caught my attention. The words “Boyhood Chums Die Overseas” and the wistful, determined and worried looks on their faces seemed to leap from the page. Even now, the looks on their faces speak of a sad fate to come. Photo: Newspapers.com

If ever there was a reason…

About an hour after reading their story and looking for more information about both men in the archives of the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Journal, I shut off my computer and began washing up and getting dressed to attend, with my wife, a belated wedding reception for two dear friends— Gerry Arial and Peter Frayne. They had been married a couple of months previously and this small intimate reception was being held at the residence of Gerda Hnatyshyn, the widow of the former Governor General of Canada, Raymond Hnatyshyn. About an hour into the evening I found myself in a lovely conversation with Peter’s mother Ruth Frayne. She asked me where I had grown up and I went on a bit too long about the beloved Elmvale Acres of my youth before I stopped myself and asked her where she was born.

“Ottawa” she replied.

“Whereabouts?” I asked

“On Faraday Street.” she answered.

Gobsmacked by the coincidence that she lived on a street that I had never heard of until just a few hours before, I went on to an excited story about my mapping project and my research and how just that day I had come across this compelling story about two best friends who had died within 24 hours of each other in England during the war. I was telling her about the two men, one of whom had a very memorable name: Zina Manford Niblock. I was speaking rapidly about coincidence, fate and the two young men when I stopped in my tracks when I noticed Ruth’s eyes begin to water.

“Are you OK Mrs. Frayne?” I asked

She looked at me with a sad smile and said words that I’ll likely never forget:

“Manny was my brother.”

If there was ever a fateful reason to tell their story it is the fact that I met the little 6-year old sister of Manford Niblock just hours after finding his story in the 1943 broadsheet pages of the Ottawa Citizen. That would not be the only coincidence attached to this story. Months later, I would learn that Ruth’s son-in-law Gerry whose reception we were attending was named after his Uncle Gerald Richardson, a Canadian Army soldier who was killed in action in Holland two years after Manny and Carl. His family home on Cooper Street in Centretown would also be pinned on the same map as Carl Caldwell’s family.

Social media — 1940s style

For the most part, it was easy to follow the military service of the young men like Niblock and Caldwell in the Second World War. The social media of the day were the broadsheet newspapers — the Ottawa Citizen and the Ottawa Journal. They were published every day of the week except Sunday and starting in the Second World War, both published a second edition Monday to Friday—The Ottawa Evening Citizen and the Ottawa Evening Journal. It was here that parents “posted” updates on the progress of their sons during the war. If a young man joined the air force and was off to pilot straining or gunnery school, his parents would send a photo to their favourite of the two newspapers and maybe even to both. A day or so later, his photo would appear in the papers accompanied by a brief two or three paragraph story about the boy, where he went to school, who his parents were and perhaps his sporting accomplishments.

As the months passed, that same photo, kept on file by the paper, would appear again and again, updating the community with new details of his progress — accompanied by headings such as Receives Wings; or Arrives Overseas and even Celebrates 20th Birthday in Great Britain. Parents were doing the 1940s equivalent of “posting on Facebook”, letting friends and neighbours know how things were going for their son and family. Then came the hard part.

Within a few days of a service catastrophe that might have befallen the same young men, their photos would appear again, but with a grimmer heading: Missing in Action; Wounded in Action; Killed in Action; or Killed in Flying Accident. These were all too common and it seemed every day brought more. If the family was lucky, they could announce to the papers a few months later that their son was Now a Prisoner of War and the publisher would dust off the old photo for the story. If they were unlucky, that heading would read Now Presumed Killed. Later in the war, those same photos might appear again with far more hopeful headings like Freed from Huns; On Way Home; or best of all, simply Arrives Home.

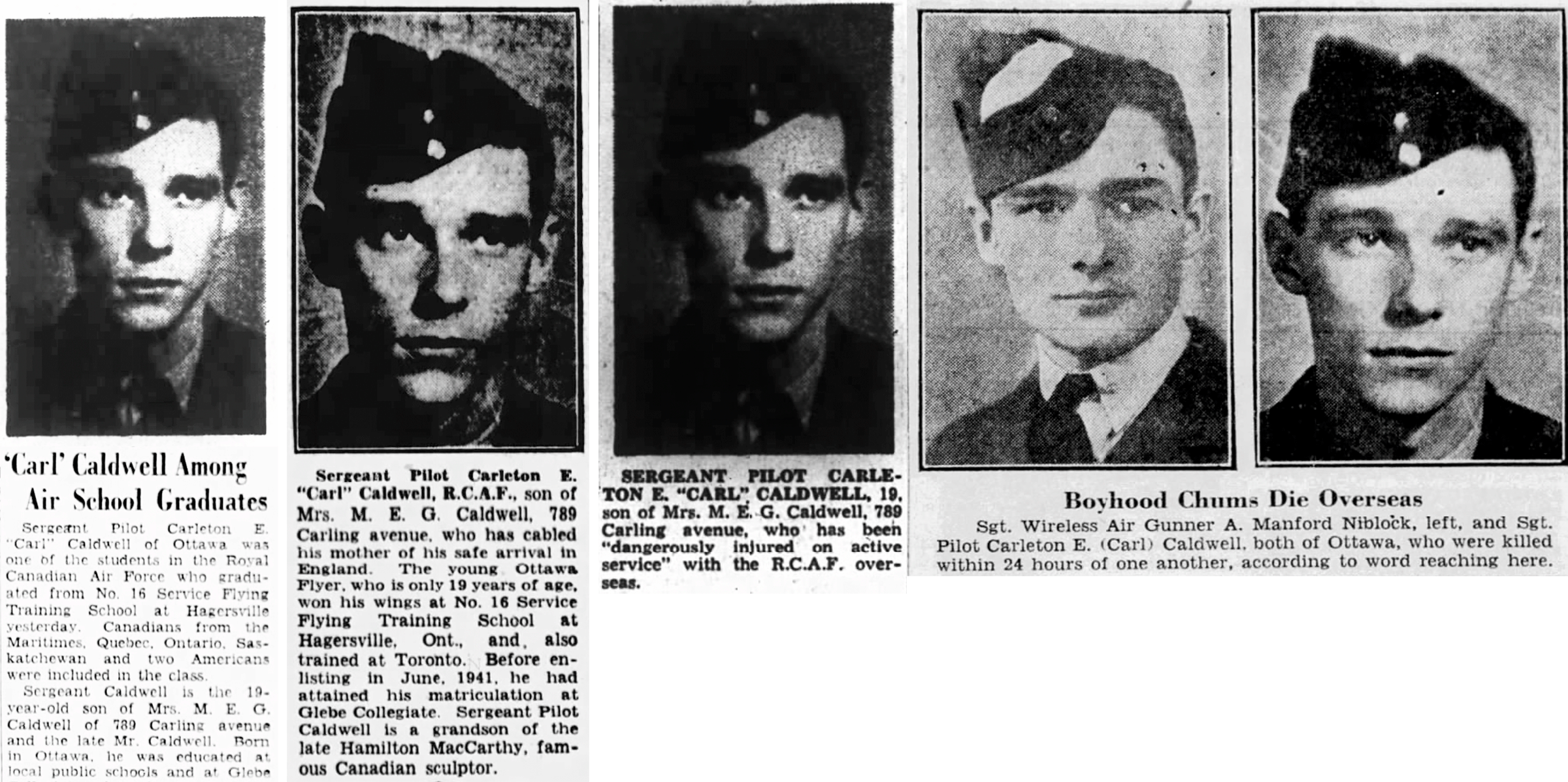

A typical series of news pieces for Carl Caldwell fell, as most did, into a set pattern. Initially Caldwell’s mother Gwen sent a photo to the Ottawa Citizen when her son graduated from pilot training in December of 1941. Upon his arrival in Great Britain he cabled his mother that he had arrived safely and she contacted the newspapers to announce it to neighbours and friends (second from left). When she learned that he had survived but had been seriously injured in an airplane accident in May, 1942, she shared that news too (middle). And finally Carl’s death in the same 24-hour period as his best friend Manny Niblock. Clippings from Newspapers.com

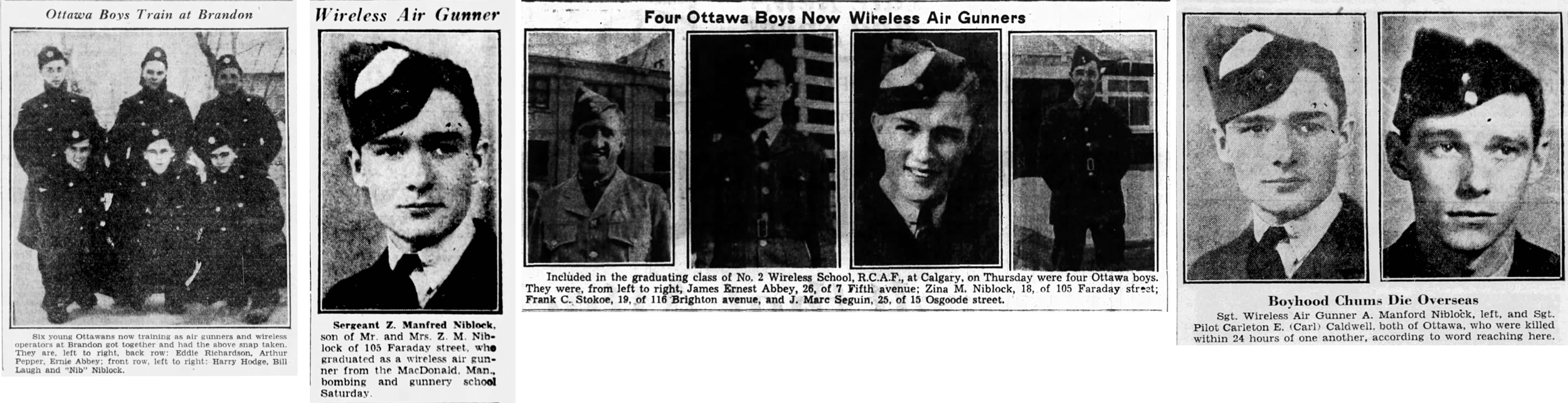

Manny Niblock’s photo appeared several times in the Ottawa papers. At left, the RCAF gathered the six Ottawa boys at No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School in Macdonald, Manitoba together for a publicity shot which they knew would be a big hit in Ottawa. It also helped to alleviate parental fears that their sons were isolated and homesick. Later, following his graduation and his wings ceremony, his parents proudly announce his accomplishment, followed by another announcement from the Department of Defence about four graduating wireless/air gunners from Ottawa. Then sadly, only a few months later the joint announcement and human interest story of Manny and Carl’s deaths so close together in time and space. Clippings fro Newspapers.com

Growing up in Ottawa

Both Manny Niblock and Carl Caldwell grew up in neighbourhoods relatively far apart but still in the same school catchment area. Caldwell and his family lived on Carling Avenue at Dow’s Lake, today the scenic site of the Canadian Tulip Festival, Winterlude, Commissioner’s Park, paddle boaters, winter skaters and kayakers and Beavertails. But back when Carl was still just six-years old, it was more industrialized with much of the surrounding area utilized for lumber storage from the big saw mills at Chaudière (they were brought the short distance from Chaudière on rail cars) and the lake, today one of the crown jewels in Ottawa’s National Capital Commission park system, was just beginning to be redeveloped. At that time, a raised causeway transected the lake from Preston Street to the southeast shore. When the Rideau Canal system was drained each winter to prevent ice damage to the stone walls, the bottom of the lake was spiked with hundreds of tree stumps, evidence of Dow’s Great Swamp which was drained and lumbered by Colonel John By’s engineers in the early 19th century. By 1930, the lake had begun its transformation to urban parkland with the removal of the lumber stocks and causeway and the building of the Dows Lake Boathouse.

Despite his modest home’s proximity to a less-than-scenic industrial landscape, Caldwell was from a respected Canadian family. He was the great grandson of British monument sculptor Hamilton Wright MacCarthy and the grandson and namesake of British-born Hamilton Thomas Carlton Plantagenet MacCarthy, Canada’s leading monument sculptor of the early 20th century. Carl’s father, James Ernest Caldwell, had been a well-known Ottawa lawyer but had died when Carl was just five years old in June of 1928. According to news reports, he was killed by the accidental discharge of his rifle which he was apparently cleaning. The gun was still in its canvas bag when it discharged. He blew the right side of his head off. It was a borrowed rifle and no one heard the shot. One wonders if that was covering for a suicide and knowing his insurance would not pay out if suicide was obvious. He left most of his sizeable estate of $28,400.00 (nearly half a million in today's dollars) to his two sons, Carleton and Dalton. Carl’s two sisters, Winnifred and Winona, from his mother Gwen’s previous marriage at 17 to a 40-year old widower by the name of William Withrow, received little from their stepfather.

Lieutenant William Withrow, a civil engineer, went overseas with the 2nd Canadian Pioneer Battalion in March 1915, leaving his 24-year old wife at home with their two small children. Overseas, he was transferred to the command of a machine gun company and led it in the battles at St. Elois, Ypres and the Somme. In 1917, he was appointed to the command of the Canadian Topographical Section, which he organized, and he did important service in preparing the plans for the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Though exhausted by his work and his two years at the front, he refused leave, and accepted a new position as quartermaster for his old battalion. On the first day of his new duties, he dropped dead of heart failure, leaving the young Margaret Eleanor Guinevere (Gwen) MacCarthy a widow. Ten years later, Gwen would become a two-time widow when her second husband James blew his face off in his office.

Hamilton MacCarthy, prolific and respected monument sculptor. Photo: Wikipedia

SIDE BAR 1: A family of icon makers. A number of Hamilton MacCarthy’s works grace Ottawa’s Parliamentary District two kilometres to the northeast of Carl’s home including the monument to Alexander MacKenzie, Canada’s second Prime Minister and a massive monument of Samuel de Champlain. The sculpture was created in 1915 by MacCarthy and was intended to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the arrival of explorers from Europe in this part of the world. It featured a swashbuckling and moustachioed figure of Champlain, cape flying in the wind, looking to the west with his astrolabe (a navigation instrument) raised high. Three years later in 1915, MacCarthy added the figure of a kneeling indigenous guide to the base. Originally the guide was intended to be kneeling and paddling in a canoe, but not enough money could be raised to complete the design and instead, the hunter knelt in the ground, looking out to the north west. The two figures stood atop Nepean Point for almost 100 years and children, including my own, posed for photos sitting upon the native guide’s knee. One can imagine Carl Caldwell doing exactly the same in the late 1920s or early 1930s. In the 21st century, however, the placement of the native guide was seen as subservient or at least secondary to the figure of Champlain. In truth, Champlain’s celebrated exploration the Ottawa Valley and western Québec was something indigenous hunters and traders had been doing for centuries. The two figures were separated, with the guide moved nearby to Major’s Hill Park and given its own title: Anishinaabe Scout and Champlain removed from the heights of the point to a place in the surrounding park. Nepean Point lost its Cornish name, and was renamed Kìwekì Point. Kìwekì means “to return to one’s homeland” in Algonquin.

MacCarthy’s other works include the Boer War Memorial in Ottawa, the Sir John A. Macdonald Memorial at Queen’s Park Toronto, and Boer War memorials across the country. It is interesting to note that when the elder MacCarthy died in 1939 at 93 years of age, he was living at 739 Carling Avenue in the home of his daughter, Gwen Caldwell.

MacCarthy’s son and Carl Caldwell’s uncle, with the magical name Coeur de Leon “Leo” MacCarthy took up the family business and became an equally respected monument sculptor whose works include several the First World War memorials across the country. His most famous work was The Angel of Victory, a bronze, seven foot tall statue depicting a fallen soldier being carried toward heaven by a female angel. It was commissioned in 1922 in memory of the 1,116 Canadian Pacific Railway employees who died in the First World War. Copies of the statue were also installed at CPR stations in Vancouver and Winnipeg. The Winnipeg copy has since been moved from the station, and is now located outside the Deer Lodge Hospital.

MacCarthy’s work can be seen from Victoria, British Columbia to Halifax Nova Scotia. Several of his works have been the subject of controversy in the past decade, suffering historical reset. His most famous work (top row) was the statue of Samuel de Champlain, the respected founder of New France. On the bottom row are three other bronze monuments by MacCarthy —Alexander MacKenzie, Canada’s second Prime Minister on Parliament Hill; a bust of General Sir Isaac Brock, hero of the War of 1812, in Brockville, the city named after him; and a monument to Eggerton Ryerson, the one of the creators of the Canada’s public school system which stood in Toronto for more than 100 years. While Ryerson was instrumental in building the public school system, he was also instrumental in creating the Indian residential school system which was one of Canada’s greatest shames. This statue was toppled in 2021 and decapitated. The head ended up on a pike at an Ontario reservation. At right is Coeur de Lion MacCarthy’s Canadian monument icon “Angel of Victory” at Montréal’s Windsor Station. Images via Wikipedia

Manny, on the other hand lived farther to the west at 104 Faraday Street, about 2.5 kilometres to the west of Glebe Collegiate. but certainly not too far to walk or bicycle. If the weather was cold or raining he could walk to the Holland Junction station at Carling Avenue where he could keep warm until the arrival of the Crosstown bus. The Ottawa Transportation Commission bus would take him east on Carling right to Glebe Collegiate. He wouldn’t have long to wait for the OTC operated nearly 200 round trips of the Crosstown every day.

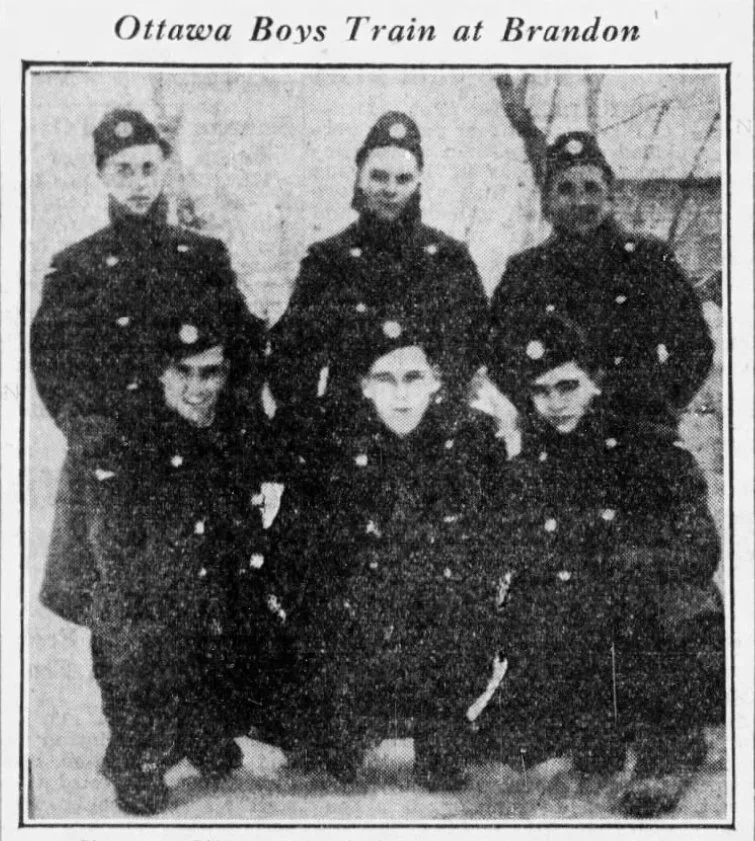

Carl Caldwell and Manny Niblock attended both Elmdale and Devonshire Public Schools. Devonshire was built in 1901 and originally named Breeze Hill Avenue School. When it was expanded in 1920, it was renamed to honour the Duke of Devonshire, the Governor General at the time. Photo via Old Ottawa and Bytown Pics group on Facebook

They had spent much of their young lives together, likely meeting at Elmdale Public School as small boys. They both transferred to Devonshire Public School on Breezehill Avenue in Ottawa. Both attended Glebe Collegiate Institute, a new high school at the corner of Bronson Avenue and Carling, just a short 300 metre walk uphill from Carl’s family home at Dow’s Lake

Both boys were eager to work in their spare time. Carl worked in the summers of 1935 to 1940 as a caddy at the exclusive Ottawa Hunt and Golf Club — a seven kilometre bike ride down Prince of Wales Drive to Hogs Back where he crossed over to River Road and on out to the “Hunt Club”, situated next to Uplands Aerodrome, the site of the Ottawa Flying Club and the place where Charles Lindberg landed for Canada’s Sesquicentennial celebrations in 1927. By 1940, it was a very busy commercial airfield and military base, soon to be the home of No. 2 Service Flying Training School. It was here, on those summer afternoons on the fairways of the golf course that Carl fell in love with flying.

Glebe Collegiate Institute was built as a satellite facility of Ottawa Collegiate Institute (now Lisgar Collegiate) a mile to the north east. Now a decidedly inner city school, it was at the time of its construction thought to be on the far outskirts of town. The school opened officially in 1923 (above) and was doubled in size just four years later to accommodate the classrooms of the Ottawa High School of Commerce. Photo via Old Ottawa and Bytown Pics group on Facebook

Manny took employment in the summer months after graduation as a messenger boy and stockroom clerk at J. R. Booth Ltd. No doubt Zina, his father, who was employed as Superintendent of Stores at lumber baron John Rudolphus Booth’s massive lumber company, had something to do with the young lad getting the job. As Superintendent of Stores, Zina Niblock Sr. was responsible for Booth’s considerable lumber stores which filled much of the area around Victoria Island and which had at one time stretched as far south as Dow’s Lake. He would have been responsible for the safe drying of the lumber stock and the disposition of the lumber once it had reached full seasoning.

Carl and Manny were similar in build and age. They were born just a couple of months apart in 1922. At the time of his enlistment, Carl was 5’-10” and 140 lbs., while Manny Niblock was 5’-10 1/2” and 138 lbs. Both boys loved sports, but especially skiing, joining other boys and girls on the ski bus to Camp Fortune from Glebe Collegiate.

The King’s Shilling

The boys were teenagers in high school when war was declared on September 3, 1939. Carl turned 17 the very next day and Manny followed just three weeks later on the 29th of September. With their parents’ permission, they were now eligible to join the military. Manny had his year in high school to complete first, and he had just started. After completing his third year of high school and spending the summer working at the J. R. Booth pulp and paper mill at Chaudière Falls, 17-year old Manny Niblock asked his parents, Zina and American-born Eva, for written permission to enlist and took the street car to the RCAF enlistment office at 90 O’Connor Street to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force. After filling in his attestation paper on August 16th, the recruiting officer, Flight Lieutenant Edward O’Leary shook his hand and set a date for him to return for his medical.

By the end of the month he was answering the questions of the medical examiner. Still just 17-years old, he admitted to smoking half a pack of cigarettes a day and “the odd glass of beer” even though the legal drinking age was 21. Noted numerous times in his report was his chronic appendicitis and recent appendectomy.

The modest Niblock house at 105 Faraday Street. The house has recently been demolished to make way for a pair of semidetached homes. Photo: Google maps.

Now that he had “taken the King’s Shilling” and received his service number (R/82624) he went home to Faraday Street and continued working at the pulp and paper mill, awaiting the call to turn out for service. After the new year in 1941, he got a letter from the Department of Defence and a one-way train voucher for Manning Depot in far away Brandon, Manitoba.

In the overheated car of the CNR passenger train from Ottawa, he travelled through the dark Canadian winter, the light from the frosted windows riding the snow drifts across Northern Ontario and out on to the prairies. He found himself among plenty of young men just like him headed to the Manning Depot in Brandon—five others from the Ottawa area in fact. They were mostly boys who had gone to Ottawa Technical High School — Art Pepper, Ernie Abbey, Bill Laugh. Harry Hodge, at 26, was hard to relate to for a 17-year old, but had gone to Glebe Collegiate. Eddie Richardson with his Scottish brogue hailed from Richmond, Ontario which was close to where Manny’s farming cousins lived in North Gower. At 31, he was closer in age to Manny’s father than to Manny.

After a few hours wait in Winnipeg, the trained pulled out for Brandon, the “Wheat City”, an agriculture-based city of some 17,000 hardy souls out on the bald prairie. Brandon was a major part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan System (BCATP) — home to No. 2 Manning Depot, No. 12 Service Flying Training School and No. 25 Pre-Aircrew Education Detachment (where recruits could get supplementary education in mathematics, physics and English in order to meet RCAF aircrew standards). It remains an important part of the BCATP story to this day as the home of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum and the RCAF WWII Memorial.

Niblock and the others were taken on strength at No 2 Manning Depot on January 21, 1941, issued their kit and new uniforms, had their hair cut and were given the rank of Aircraftman Second Class or AC2, (“Acey Deucey”). They were starting at the bottom. They were among 20 new recruits to arrive that day. Thirty others were leaving the depot as they were arriving. They must have wondered what they were getting into. The weather bottomed out at minus 14 degrees Fahrenheit (Minus 27 Celsius) that day and the sun disappeared around 5 PM. They were assigned their bunks in former cattle stalls in an annex to the vast, draughty and dimly lit arena known as the Brandon Winter Fair Building at the corner of Victoria and Eleventh Streets. They dined in an old poultry barn annex and marched on the floor of the former uninsulated ice hockey arena.

Niblock (right front) poses with five other Ottawa boys for an air force photographer at No. 2 Manning Depot in Brandon, Manitoba in February of 1941. The RCAF knew the importance of gathering up airmen from one city and taking their group photo so that folks back home could see the impact “their boys” were having on the war effort. The photo appeared in the Ottawa Citizen on February 11, 1941, about halfway through Manford Niblock’s time at Brandon. The men in winter great coats are identified as (Back row, L-R: Eddie Richardson, Arthur Pepper, and Ernie Abbey. Front Row: Harry Hodge, Bill Laugh and “Nib” Niblock. Eddie Richardson of Richmond, Ontario was also lost on operations in Egypt — on October 15, 1942. Arthur Pepper was lost in Egypt as well… just eight days later whilst flying with 462 Squadron RAAF — the only Halifax-equipped unit operating from Egypt in 1942. Image: Ottawa Citizen via newspapers.com

At Manning Depot, raw recruits, fresh from college, high school, or the factory floor came to learn how to leave their civilian lives behind. Here they got their haircuts, their issue uniforms and learned to live without privacy, home-cooked meals or peace and quiet. The “sprog” airmen learned the fundamentals of life in the King’s Royal Canadian Air Force — proper wearing of uniform kit and cap, marching, saluting, identifying rank badges, marching, basic air force law, marching, small arms and physical training and more marching.

No. 2 Wireless School on Calgary, Alberta

Manny remained in Brandon for the next five weeks, being struck off service there on March 1st. By this time it was already determined that he was not going to be selected for pilot or navigator positions in an aircrew. If he had been, he would then go on to an Initial Training School (ITS) for further training and assessment. Instead, he was posted immediately to No. 2 Wireless School in Calgary, Alberta, there to learn the wireless radio operator craft. He was taken on strength there a day after leaving Brandon on the westbound train. The No. 2 Wireless School daily diary for March 2, 1941 states that “Fifteen Wireless Operators (Air Gunner) reported for Guard Duty from #2 Manning Depot.” Manny was one of those 15 young men.

The school was housed in the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art (Today, the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology), a post secondary college which was taken over by the RCAF to house the new wireless school. Thousands of young men from across the British Commonwealth would arrive here over the five years of its existence, many to learn the trade that would take them to their deaths.

Though the now 18-year old Manford Niblock had arrived at the school where he would eventually learn his trade, he did not escape “guard duty”, a form of penance most air crew trainees were ordered to make after Manning Depot. In the performance of their guard duty they were given monotonous, simple and in some cases useless tasks to keep them busy until a spot opened up on a radio course or just to get them used to being an airman. One of the most common of these otiose tasks was “Tarmac” Duty — guarding the gates to RCAF stations and other RCAF property such as downed aircraft and broken down equipment. Manny did his penance at No. 2 WS before he started his wireless course.

At the end of March, he joined 200 other ranks and officers in a “Patriotic Parade” in down-town Calgary in the interest of the Canadian War Service Fund. At this point, the school had 916 trainee radio operators. It is not known when exactly Manny went from guard duty to officially joining a course at the school, but when he did he was finally entitled to wear the white cloth flash in his wedge cap that signalled to the world that he was training to join an air crew as a wireless operator/air gunner. Here he learned the basics of Morse code, signals, radio operation and repair and spent hours in the air in aircraft like the Noorduyn Norseman and the Menasco-powered Tiger Moth learning to read radio beacons and send messages under the stresses of flight. When he was finished, he had been at the school for more than half a year, graduating out on September 12, 1941, and being posted to No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School in MacDonald, Manitoba. Manny was not the most outstanding example of a radio operator, graduating 82nd out of 199 graduates from No. 2 WS, but he was fully qualified to sew on the sleeve badge of at the wireless operator trade, depicting a fist clenching three lightning bolts. He had yet to qualify to wear a winged air crew brevet, but that was only months away.

Carl takes the King’s Shilling

While Manny had been slogging it out on guard duty and radio training at Calgary, his best friend Carl Caldwell, who had stayed in school a bit longer, entered the recruiting centre on O’Connor Street on May 4, 1941 and enlisted in the RCAF. His attestation papers report that he was deemed confident, upright in stature, athletic in build, neat in appearance, quick to respond, and clear spoken — just the kind of material that recruiters were looking for. An assessment by the intake recruiter stated: “Very bright young man with a pleasing personality, Keen to be a pilot and should improve with discipline and training.” All in all, a good start to Carl’s dream to become a pilot.

Airforce recruits right dress in front of the Sheep and Swine exhibition hall at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto. Photo via BCATP.wordpress.com and the Frank Sorensen collection

Where Manny had waited a couple months after enlistment to be called up, Carl entered his training period almost immediately. Within a couple of weeks, he found himself on the train to Toronto, rolling through Eastern Ontario farmland in fine and cool Spring weather, excited about his future, nervous about how well he would do and already missing his mother and brother Dalton.

He arrived at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto and was taken on strength on May 14th, just ten days after signing up. It is likely that, since his best pal had proceeded him in the Manning Depot experience by almost four months, Manny had written letters to him describing the miserable conditions — sleeping in cattle stalls and drilling in an echoing and freezing rodeo arena in small town Manitoba. If Carl thought that his Manning Depot experience would be different in Toronto, then the second largest city in Canada and a bustling and sophisticated metropolis, he was soon put straight.

The Coliseum at Toronto’s exhibition grounds served as an indoor parade square where recruits like Carl Caldwell learned to march. Photo: Toronto Archive

Like No. 2 in Brandon, No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto resided in an agricultural exhibition hall — The Canadian National Exhibition Coliseum. The comforts were much the same as in Brandon with “Acey Deucies” sleeping four to an animal stall. On hot summer nights, recruits could detect the powerful scent of the stalls’ original tenants. Marching was carried out mostly outside, but in inclement weather, the floor of the coliseum echoed with the commands of drill sergeants. Carl was subjected to the same abuses, humiliations, tests, courses and demands as Manny had in previous months. The only upside was the many attractions and things to do in Toronto on the rare afternoon or evening when Carl was off duty.

He was at Manning Depot for less than two weeks when he was sent off on May 29th guard duty — at No. 4 Bombing and Gunnery School, about 200 kilometres southwest of Toronto on the shores of Lake Erie. His Manning Depot time was extraordinarily short. The average was between 4 and 5 weeks, with his pal Manny getting it done in five, but Carl was off to guard duty after just 14 days. There is no evidence that he returned to Manning Depot. and he was still at Fingal on July 15th when he was finally struck of strength at No. 4 B&GS. Hard to believe. Given his fast-as-lightning passage through Manning Depot, it’s strange that he would then spend a month and a half doing meaningless duty at Fingal. His records show this in more than one place, so it’s not a hand-written typo.

After his early summer of easy duty on the shores of Lake Erie, he was posted to No. 1 Initial Training School at Toronto’s Eglinton Hunt Club, arriving there amid a vicious electrical storm on July 16th. Following Manning Depot and guard duty, prospective aircrew like Caldwell who were thought to have potential for pilot or navigator training were posted to an Initial Training School (ITS). It was here that they learned the basics of airmanship, aerodynamics, meteorology, mathematics and even some simple flight control and navigation in diminutive Link trainer simulators. The results of their tests at ITS determined their next posting. Everyone wanted to become a pilot, but many would not. Truthfully, if the RCAF was short on navigators or bomb-aimers at the moment, perfectly suitable pilot candidates could be sent to navigation or bombing and gunnery schools to fill the voids. The ITS courses demanded diligence and lots of study and often required an academic background beyond the limits of high school graduates. Tests also included an interview with a psychiatrist, the four-hour long M2 physical examination and a session in a decompression chamber. At the end of the course, the flight or navigation postings were announced. Occasionally candidates whose marks were low were re-routed at the end of ITS to the same Wireless/Air Gunner stream that Manny was in.

Carl finished up ITS a month later (at 86th out of a class of 182, his was also not a stellar finish) and received the best possible outcome — approved for the pilot training stream. On August 20th, his last day at No. 1 ITS, the station was turned out in their parade ground best, not to say good bye, but to welcome His Royal Highness, Prince George, The Duke of Kent and brother of the King. The Duke, a qualified RAF pilot, toured the station and spent some time with the staff and students there, complimenting them effusively. He signed the station guest book which had been presented to the station by the students of the first graduating course the previous year. It was noted in the school diary that, when the Duke signed it, there were over 6,000 other signatures of students and staff already in the book, a testament to the scale of training at just this one station.

Unfortunately, Carl Caldwell and 83 other successful ITS graduates could not be there to witness his visit as they were bussed by government transport 55 kilometres east along Highway 2 on the north shore of Lake Ontario to RCAF Station Oshawa, a recently completed airfield housing the hangars, barracks, aircraft and staff of No. 20 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS). The station had only been operating for eight weeks and was under civilian management. Here, for the next seven weeks, the 86 students (two were added from other sources), known collectively as Course 36, would, with the help of dedicated instructors, learn the basics of flying on the de Havilland Tiger Moth.

Pairs of student pilots and instructors head to their Tiger Moths at No. 20 Elementary Flying Training School, Oshawa. Photo: Library and Archives Canada/DND

Three days later on August 23, the students of Course 36, who had missed the Duke of Kent’s visit in Toronto, were on hand this time when he arrived at No. 20 EFTS to officially declare the station open for business. At 10:40 AM that morning, the sky was clear with brilliant sunshine when two silver RCAF Lockheed Lodestars landed with the Duke and his civilian and military entourages. The Duke, in summer khaki drill uniform of an RAF Air Commodore was driven by car the hundred yards to the parade square where Carl, his cohort and the entire station stood at attention as his ensign was broken out on the flag staff. While inspecting the trainee pilots, HRH stopped to speak with several of them. Perhaps Carl was in ear shot. Following the inspection, Carl and the others gave the Duke three rousing cheers as he left for a tour of the General Motors plant in Oshawa, now retooled to build military vehicles. A year later to the day, the Duke took off in a Sunderland flying boat from RAF Invergordon bound for Iceland. It never made it out of Scotland, crashing into a mountainside on the east coast of Caithness, Scotland’s most northern county. He was the only member of the royal family to have died on active service for more than 500 years.

Attrition killed the pilot dreams of 17 of Carl’s course mates who were washed out along the way. Carl’s training went well enough though, and he graduated in the top half of his class, 23rd out of the 69 who eventually made it through. His record includes an assessment by Mr. Weisbrod, the civilian Chief Flying Instructor: “This student is above average and is quick to learn. He is a very hard worker. Instrument flying is very good. Aerobatics average.” He had by this point accumulated 59 hours flying time, 28 of them solo.

On October 3, 1940, Course 36 held a graduation dance in the General Motors Auditorium in Oshawa, with civilian and RCAF instructors in attendance. The instructors had been working hard to get the syllabus completed for Course 36, specifically the 50-hour and instrument tests on all 69. Originally scheduled for October 7th, the course finally was passed on October 10th. Only 62 of the original 86 managed to complete the course. A final tally of 23 were washed out or CT’d (ceased training) while one, LAC Joseph Claude Marcel Desrosiers, had been sent back to Manning Depot No. 4 in Québec City to take a course in English and did not graduate with the others. He had gone through his ITS section in Québec and had lasted only 10 days as part of Course 36.

AC2 Claude Derosiers, August, 1941. Image via Newspapers.com

SIDEBAR 2: Curious about Carl’s classmate Desrosiers’ career path after failing to pass the flying tests, I dug up his service file and traced his path from 20 EFTS. Weisbrod, the CFI offered up this cruel assessment three weeks before: “This student is handicapped tremendously, in that he hasn't sufficient knowledge of the English language to understand his instructor, seems mentally slow, lacks the usual French alertness. Very poor pilot material.” He was retained at Oshawa for further instruction with Course 38. One of his instructors wrote: “This student is mentally unfit for flying duties. Seems none too anxious to fly; also cannot hear and cannot understand. Does not have a good enough understanding of the English language to absorb instruction. Is slow to react to questions even on the ground.”

Harsh words for a young volunteer who simply did not have the English language skills needed. The Chief Supervisory Officer Flight Lieutenant Newsome offered this kinder conciliation:

“It is considered therefore that in fairness to the pupil, he should have an opportunity to better his knowledge of English before resuming flying training. Pupil should be posted to a French Elementary Flying Training School.”

Thanks to Newsome, he was eventually transferred to No. 22 EFTS at L’Ancienne-Lorette, Québec where he completed 32 hours of training on the Tiger Moth before being washed out for failing the navigation course. Again, his training was thwarted by his understanding of English, something that proper sequencing of training could easily have avoided. The Commanding Officer at L’Ancienne-Lorette stated:

“This airman’s failure at examinations is hard to understand, since he was good enough to help other pupils before examinations. Since he has 32 hours of flying, serious consideration should be given his case before ceasing his training as a pilot finally. Probably a transfer to a French school would help put him though. ”

Because of the poor management of his training and despite the considerations he was given by sympathetic instructors at No. 22, he was washed out again and sent to Composite Training School in Trenton, perhaps there to learn English finally. After that he went to No. 4 Bombing and Gunnery school adjacent to Trenton at Mountain View, Ontario, there to finally graduate as an Air Gunner. Sadly, he was lost on operations on January 29th, 1943 when his 420 Squadron Wellington bomber failed to return from a bombing raid against the submarine base at Lorient, France. It is sad indeed to see what happened to a young man who tried so hard to serve his country. He gave his life to uphold what was in those days, an English-first society.

September 1941 — the final stages for Manny and Carl in Canada

Following completion of his wireless training, Manny was posted to No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School in MacDonald, Manitoba. He was part of Gunnery Course 16 which began on September 15th. The Station Diary notes that three candidates had arrived from No. 2 Wireless School that day. Manny was one of them.

At MacDonald, Manny learned the workings and care of machine guns, the science of ballistics and the art of gunnery from a moving aircraft. MacDonald was, like every Bombing and Gunnery School in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan system, situated next to a large body of water, in this case Lake Manitoba whose 4,600 square kilometre size would serve as a safe and restricted place over which to practice gunnery and bombing. MacDonald offered courses for both gunners and bomb aimers and the course was brief compared to the six months he was at wireless school in Calgary. Classroom work was followed by gunnery practice on the field and in the air. He accumulated 10.25 hours in the back of a Fairey Battle, firing at canvas drogues towed by another Battle. The school even tallied the number of rounds he fired that month — 605 rounds on the ground, 600 rounds air-to-ground and 1,805 rounds air-to-air. Given that the Vickers K-gun used by the Fairey Battle gunnery trainer was capable of firing between 900 and 1200 rounds a minute, his whole training amounted to between 3 and 4 minutes of actual gun firing. It wasn't much experience, but it qualified him as an air gunner and he graduated 30th out of a class of 33. Regardless of his ranking, he had met the standard needed for air gunnery.

Manny Niblock took gunnery practice from the rear cockpit of a Fairey Battle Mk.I IT similar to this example. The gunner would raise the canopy behind his back to create a windbreak, but even in October when Manny was training, it must have been terribly cold being so exposed the slipstream at altitude. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

A student gunner poses with his Vickers K-gun or VGO (for Vickers Gas Operated), an iron-sighted .303 inch machine gun with a 100-round flat pan magazine mounted on top. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

His assessment called him an “average learner” which to the untrained ear might sound like a slight, but that’s not the case. Average was the baseline the air force strived for and meant that he met the high standards. The chief instructor, a Wing Commander named Ripley called him a “stodgy type”. In an earlier assessment following his intake in the RCAF the previous August, the recruiting officer described him differently: “… Nice quiet well spoken lad with a reserved disposition. Very keen, ambitious and straight forward. Pleasing personality.” It’s clear that Ripley mistook his quiet reservation for stodginess, which says more about Ripley than Niblock.

Manny now was authorized to wear the Wireless Operator/Air Gunner single wing badge that told anyone who saw him in uniform that he was qualified as aircrew. He could also remove the white trainee flash from his cap. He was immediately posted to “Y” Embarkation Depot in Halifax, there to be taken into the RAF Trainees Pool, a temporary administrative holding group for airmen awaiting embarkation and assignment to specific operational training units or squadrons overseas. He was also granted ten days of embarkation leave to see his family en route to Halifax. One can only imagine how happy his little sister Ruth was to see her big brother after a year, looking handsome and dark in his blue uniform and aircrew wings.

It was a bittersweet time, full of joy for seeing how much he had grown in confidence and maturity, but filled with parental trepidation about him going overseas. The U-boat captains were experiencing the glories of the “First Happy Time”, when ships in transatlantic convoys were sunk daily. As well, the pages of the Ottawa newspapers were salted with photos of young men from Ottawa just like Manny who were reported missing or killed in action or in accidents. Manny had changed. He was strong now, and capable, but his future was not bright if his mother and father read the papers at all. He embarked a ship in Halifax harbour at the end of October, bound for Liverpool and arrived at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre (3PRC) in Bournemouth, England 12 days later, having safely run the gauntlet of the North Atlantic Ocean. He telegraphed his parents on arrival.

When Manny Niblock graduated from No. 2 Wireless School in Calgary, he had three other Ottawa boys in his class. Both Niblock and Seguin were killed on operations and never made it back home to Ottawa. James Abbey (left) was a former shipper who enlisted in Ottawa January 20th, 1941 and trained at No.2 Wireless School (graduated 14 September 1941) and No.7 Bomber and Gunnery School (graduated 13 October 1941). He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for anti-submarine operations with Coastal Command. Frank Stokoe, a classmate of Carl’s and Manny’s at Glebe was the only one of the four to receive a commission upon graduation. He finished the war a Squadron Leader having served in India, Belgium and England. Image via Newspapers.com

On the very day that Manny received his WAG brevet, Carl left No. 20 EFTS in Oshawa and found himself the next day at the front gate of No. 16 Service Flying Training School, in Hagersville, south west of Hamilton, Ontario and close to where he did his month and a half of guard duty at Fingal. He was one of 56 recent EFTS graduates who reported for duty and became collectively known as Course 40. Like Oshawa, Hagersville was brand new, having just opened in August. This would be Carl’s advanced flying training course which, in a few months, would bring him to wings standard and for the first time he could then officially call himself a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force. For the first 8 weeks at Hagersville, Carl was part of an intermediate training squadron. This was followed by 6 weeks in an advanced training squadron and for the final 2 weeks training was conducted at the Bombing & Gunnery School at Fingal, the place where he had spent six weeks earlier that year.

Hagersville had both a multi-engine and single engine stream. Men who were destined for fighters were trained on single engine Harvards while pilots destined for bombers, transports or strike aircraft trained on the Avro Anson. Carl was selected for the multi-engine course and ground school instruction started right away. It didn't take him long to find trouble though. Ten days after arriving he was confined to barracks for 3 days for being AWOL from ground school. Reading through the entry in his General Conduct Sheet about the “crime”, it seems he was simply late for class.

Young LAC pilot trainees (note white cap flash and LAC propeller rank insignia) pose for a propaganda photo while consulting a map prior to taking off on a cross-country formation flight in their Ansons. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

Carl’s stay at Hagersville would last until January 10th of 1942, long after his pal Manny had arrived in England. During his time at Hagersville, he amassed another 70 hours of day flying of which 32.5 were solo in the twin-engine Anson as well as 12 hours of night flying with 10 of those solo. His unit commander, Squadron Leader Stanley Yendle Broadbent, a veteran bush pilot, remarked that he “Started well and learns quickly. Steady on instruments but over-controls slightly”. Broadbent would die six years later when the Trenton-based de Havilland Vampire jet aircraft he was flying plummeted into Lake Ontario near Bowmanville, about 20 kilometres from Oshawa.

He was assessed by the Chief Ground Instructor, Flight Lieutenant Guy Draper, as “A better than average student of good appearance, a hard worker with a level head.” However, as with Manny, his marks on completion of the course were not stellar but at least average. He graduated 26th out of the 51 students who made it to the end — dead centre. Group Captain G. S. O’Brian, AFC, the school’s commanding officer wrote that “Caldwell gave me an impression of deserving a higher place and of being suitable commission material.” In his final assessment he was recommended for twin-engine fighters which would have been his hope all along. This would mean aircraft similar to de Havilland Mosquitos, Bristol Beaufighters and possibly Blenheim or Havoc night fighters. Despite O’Brian’s suggestion that he was good officer material, he did not receive a commission and was promoted upon graduation to sergeant instead.

On January 10, the day he cleared RCAF Station Hagersville, a news paper report appeared in the Ottawa Citizen about his success. It read

“Carl” Caldwell Among Air School Graduates

Sergeant Pilot Carleton E. “Carl” Caldwell of Ottawa was one of the students in the Royal Canadian Air Force who graduated from No. 16 Service Flying Training School at Hagersville yesterday. Canadians from the Maritimes, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and two Americans were included in the class. Sergeant Caldwell is the 19-year-old son of Mrs. M.E.G. Caldwell of 789 Carling Avenue and the late Mr. Caldwell. Born in Ottawa, he was educated at local public schools and at Glebe Collegiate where he received his junior matriculation. He enlisted in June [sic] of last year, training at Toronto and Hagersville.”

Upon getting his pilots wings, he was granted 12 days embarkation leave and returned by train to Ottawa to visit family. He likely was happy to get out of Hagersville on that day as “the water situation” was “critical” with pipes and pumping equipment freezing solid. By January 23rd, 1942, Carl Caldwell reported to the RAF Trainees Pool at “Y” Embarkation Depot in Halifax, the same admin unit that his best friend Manny passed through a couple of months before. They were soon to be reunited.

Manny in England

During his month-long attachment to No 14 O.T.U., Manny Niblock familiarized himself with the Handley Page Hampden in which he would eventually serve with 415 Squadron RCAF. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Following his arrival at Bournemouth on November 14, 1941, Manny was attached to No. 14 Operational Training Unit at RAF Cottesmore, Rutland to gain experience in radio and gunnery on the Handley Page Hampden, a medium bomber used by Bomber Command and Coastal Command of the Royal Air Force. He was here for a month taking courses on the equipment and completing some flying. Normally, at this stage, he would join a crew along with a newly minted pilot, navigator and bomb aimer, but that process was cut short. Perhaps it was felt that, even though he had his WAG wings, he needed more radio work to make him truly operational. This jives with his lower class standing upon completion of his wireless operator/air gunner training in Canada. So, on the 9th of December he took the train to No. 2 Signals School at RAF Yatesbury, Wiltshire for refresher training and to learn the use of more sophisticated equipment. Science fiction author and screen writer Arthur C. Clarke of 2001: A Space Odyssey fame was an instructor at Yatesbury at that time.

After two months for so at Yatesbury, he was posted to No. 3 Radio School at RAF Prestwick in southwestern Scotland for two more months instruction. The school at Prestwick was cold and wet with dismal quarters and even more dismal food. The syllabus here was mostly dedicated to the new art of direction finding, airborne interception and radar. On May 4th, 1942., Zina Manford Niblock was finally posted to an operational squadron — 415 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force a newly-formed torpedo bomber squadron operating under Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force. He joined the squadron at RAF St. Eval on the north coast of Cornwall where they were conducting training and operational anti-submarine patrols. Some of the crews were up north at RAF Abbotsinch to complete torpedo training at No. 1 Torpedo Training Unit.

No. 415 Squadron was first formed on 20 August 1941 at Royal Air Force (RAF) Station Thorney Island on the English south coast as Canada's first Torpedo Bombing Squadron. Commanded by Wing Commander E.L. ‘Wally’ Wurtele, the squadron conducted its initial training on the Bristol Beaufort; by October, the squadron began serving as an operational training unit for general reconnaissance and torpedo bomber crews. In early 1942, 415 (Torpedo Bombing) Squadron converted to the Handley Page Hampden and, on 21 April 1942, flew its first operational Coastal Command mission. Over the next two years the squadron would fly anti-submarine and anti-shipping patrols in the English Channel and Bay of Biscay.

That meant that Manny’s arrival coincided with the very first anti-shipping operations conducted by the squadron. However, it would be a while before Manny was “blooded” on an actual 415 sortie. He had to go through a training phase first and be brought into a 4-man crew as a wireless operator/air gunner along with a pilot, navigator/bomb aimer and second air gunner. Being based now at RAF Thorney Island on the south coast of England, Manny finally had a home and address.

The Handley Page Hampden was one of the mainstay bombers of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command in the early stages of the Second World War. By 1942, four-engine Halifax and Sterling aircraft were proving to be better platforms for long-distance strategic bombing and shortly thereafter the Lancaster began operations with Bomber Command. With the arrival of more capable aircraft types, Hampdens were moved to a more tactical role such as the anti-shipping tasks of Niblock’s 415 Squadron. The KM squadron codes on these aircraft identify them as belonging to 44 Squadron, one of only two RAF squadrons to sustain operations continuously from the first day of the war to the last. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A Near Death Experience

A couple months before, on January 26th, Carl had sailed for England in Convoy HX-172 aboard one of 59 ships in 11 columns. Ships with names like British Integrity, Rangitiki, City of Marseilles, Marija Petrinovic or Strategist. The massive flotilla was guarded by 18 escorts of various sizes at various times en route—from 600 ton minesweepers like HMCS Red Deer to Flower-class corvettes like the near 1,000 ton HMCS The Pas to 2,400 ton speedsters like the Benson-class destroyer USS Swanson. He landed at Liverpool on February 7th. We can only imagine the excitement and wonder he must have felt disembarking a rusting cargo ship at a busy, dirty and crowded Liverpool pier with barrage balloons swaying over the harbour and the Mersey estuary. As far as the eye could see down the Mersey were the ships of his convoy being pushed into their berths by black tugboats belching dirty coal smoke. Ships from all over the world, streaked with rust, filthy, battered, were craning their cargos of munitions, wheat, petrol, cooking oils, foodstuffs, jeeps, crated aircraft and more. The air was sooty, smelling of diesel, coal and fish and reverberated with the blasts of ships horns, shouts, pneumatic riveters and the screams of gulls.

He boarded a train at Liverpool’s Lime Street Station and arrived at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth on February 10. He was held there for nearly two months until space could be made for him for refresher flying and further training. Manny was up north in Prestwick, but by now they both knew each other was in Great Britain. Things were beginning to spin up in their operational lives. On April 1st, 1943, the 19th birthday of the RCAF, Carl was struck off service at Bournemouth and posted to a brand new unit—No. 12 Advanced Flying Unit (AFU) at RAF Grantham in Lincolnshire where he could refresh his flying skills and build up more hours on Airspeed Oxford and Bristol Blenheim aircraft. The AFU, which was created just days before his arrival there, allowed the Royal Air Force, which would employ him in a squadron under their command, to assess his abilities and then find him a suitable posting to an Operational Training Unit. For Carl, that would not come for another seven months.

Aerial oblique view of RAF Grantham, Lincolnshire, from the north. Airspeed Oxfords of No. 12 (Pilots) Advanced Flying Unit can be seen parked in front of the hangars in the foreground, and by the airfield boundary with the A52 highway, at top left. Carl would have lived in one of the H-hut barracks at middle right during his seven months at Grantham. Photo: Imperial War Museum

At Grantham, the recently promoted Flight Sergeant Carl Caldwell built experience on the Air Speed Oxford, a British-designed multi-engine trainer. He very nearly lost his life piloting one solo on a foggy night in May 1942. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The crash that nearly killed Caldwell took place on May 21, 1942 at RAF Harlaxton, a relief landing field used by No. 12 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit at RAF Grantham a few kilometres northeast as well as RAF Cranwell fifteen kilometres beyond that. He crashed his Airspeed Oxford short of the runway at 03:50 AM local time while trying to return to Harlaxton upon finding himself in dense fog. He was the only one on board for the training mission. His testimony following the crash, likely written during his stay in hospital reads:

“I took off in Oxford Aircraft No. W6649 on Night Flying Training, turned cross wind and found that the flare path [runway lighting] was invisible. By flashing my landing light I realized it was a dense fog. At first the fog was patchy so that I could get occasional glimpses of a few of the lights of the flare path. This happened several times and each time I dived at the flare path trying to get my wheels down and come in, but before I could do this the lights were obscured. Flying very low I found the beacon once, I set course from it to the flare path, when I estimated I was over the flare path, I tried to come down thought the fog in a continuous medium turn. Once, perhaps twice, I came down very low according to my altimeter and I climbed again. I tried coming through again in the hope that the fog was sufficiently high off the ground to allow me to see the lights and land. I learned some months later that the fog was right on the ground. It seems I must have flown straight in and crashed a couple of fields away from the flare path, That is all I remember.”

When Caldwell was freed unconscious from the wreckage he was found seriously injured from striking his face against the control panel. He had facial lacerations and a fractured jaw. At 04:30 AM he was taken by ambulance to the Station Sick Quarters at Harlaxton, then on to the RAF Hospital at Rauceby. Rauceby Hospital (the former Kesteven County Asylum mental institution) was where famed plastic surgeon and burn recovery specialist Dr. Archibald McIndoe worked along with other members of the "Guinea Pig Club"

Meanwhile…

During Carl’s time in hospital, Manny was training for his role as a Wireless/Air Gunner on a torpedo bomber which would be conducting anti-shipping and ant-submarine operations in waters surrounding the United Kingdom. On the day he arrived on squadron at St. Eval, the unit diary noted “There seems to be a decided speeding up of efforts to bring the Squadron to full operational strength, and it is anticipated that more crews will soon be available for Anti-submarine patrols.”

It was Manny’s job to man the twin Vickers K guns n the dorsal position of his Hampden as well as managing radios. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On May 16, Manny and the bulk of the squadron packed up and moved en masse back to Thorney Island. It wasn’t until June 23rd, when Manny, as WO/AG with the Cross crew in Hampden “A” for Apple (RAF Serial No. AT232), took off at 1045 PM carrying an 8-foot torpedo on an anti-shipping strike along the German-held Danish coast at the estuary of the Elbe River. Manny operated the twin Vickers K-guns in the rear turret watching out for enemy aircraft approaching from behind and above. When required he also operated the radio equipment — the Marconi R1155 receiver and Marconi T1154 transmitter. They were in the company of another Hampden (“N” for Nuts) from 415 Squadron and a Lockheed Hudson of 59 Squadron which also operated from Thorney Island. During the sortie they lost contact with the other two aircraft, encountered flak off the Frisian Islands and at about 1:30 AM sighted two large patches of oil flaming on the water in the dark of night. There was no shipping traffic encountered and they returned to base after 3:30 AM, the entire flight being flown in pitch darkness.

At this point, it seems as if Manny was either having some difficulty achieving the standard necessary to make him a regular wireless/air gunner on the squadron or the squadron had an overabundance of members. By August, three months after joining the squadron, he had flown only once and he was listed in the Squadron Nominal Roll of Airmen as “supernumerary to B-Flight”, meaning he was superfluous to the present needs of the unit. To be fair, there were 12 other airmen listed as supernumerary in various crew positions.

According to Ottawa newspapers Manny and Carl had seen “a lot of one another overseas” and it is likely that Manny would have heard about Carl’s accident through his family or possibly from Carl directly. There is no proof, but it is most likely that Manny, during this period of supernumerary inaction, was granted leave to visit Carl at Rauceby Hospital at sometime during his recovery.

The 415 Operations Record Book (ORB) is missing pages with details of crews for operations in August and September, so it’s impossible to determine whether Manny was flying in those weeks, but it’s possible. He did not fly on operations throughout October, November and December as he does not show up in the ORB which was complete. He had been on squadron strength now for eight months, yet had flown on operations possibly only once.

At the end of November, Manny was officially reprimanded by Group Captain O.I. Gilson, the base commander at Thorney Island for having all the buttons of his greatcoat undone and with his hands in the greatcoat’s pockets “whilst walking out in uniform”. Sounds like Gilson was a right bastard. The next recorded sortie Manny made was after New Year’s Day, when, on January 3rd, he joined the crew of Hampton “K” for King on a six-ship daylight anti-shipping strike. They took off at 12:44 PM from RAF Preddanack on the southernmost point in Cornwall, headed for the Bay of Biscay. An enemy motor vessel of approximately 2,000 tons was reported heading due east west of Lorient, France, a major German submarine base.

415 Squadron’s Hampdens were part of Coastal Command of the RAF and they were tasked with strikes on enemy shipping along the North Sea coast of Europe — From Norway to Belgium — and the Bay of Biscay. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On sighting the ship ten miles off the coast, they split into two flights and attacked from opposite sides. However, both flight commanders called off their attacks when they realized the reported ship was only a 500-ton coaster and did not need the mass attack to be dealt with. One pilot was tasked with attacking with his torpedo while the five others strafed the ship with the navigator’s single Browning .303 and their ventral guns upon passing over it. Manny could not engage the ship from the dorsal position. The torpedo missed the stern of the ship by 20 yards, exploding 400 yards beyond. No verifiable results were obtained and the coaster somehow managed to escape to Lorient. The aircraft crews were lucky that they were not set upon by enemy fighters this close to Lorient, for at the same time as they were attacking the ship, a strong force of American Flying Fortresses were attacking the submarine base and capturing the attention of Luftwaffe aerial defences.

Throughout the rest of January, there was a lot of training going on and the squadron flew operationally only one more time, on the 17th. At this time, the squadron had moved to RAF Docking. Training flights were not listed with crew members, just the aircraft commander’s (pilot’s) name, but Niblock was in it now and likely trained heavily throughout the month.

One good thing that happened in late January was that Manny’s younger brother Keith, who was with the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve, had some leave whilst in Great Britain and the two of them spent a weekend together. It would be their last.

February, 1943

The Bristol Beaufighter strike aircraft. The RCAF had four Beaufighter-equipped squadrons in the Second World War — 404, 406, 409 and 410. Photo: Imperial War Museum

In the months leading up to February, 1943, Sergeant Carl Caldwell had been busy. On November 3rd, he was finally well enough to return to flying and was taken on strength at No. 60 Operational Training unit at RAF Leconfield, Yorkshire. A couple of weeks after Carl’s arrival, the OTU was renumbered No. 132 OTU and moved to RAF East Fortune near Edinburgh, but the mission was the same: to train pilots for long range fighter and strike aircraft operations using the Bristol Blenheim, a British light bomber, and Bristol Beaufighter, a British multi-role aircraft. 60/132 OTU got them familiar with the aircraft they would use.

Carl trained first on the Blenheim, then moved on to the more challenging and lethal Bristol Beaufighter. The Beaufighter, with the arcs of its two propellers spinning just ahead of the nose of the aircraft, was once described as “a fuselage in hot pursuit of two engines.” It was a powerful and very capable attack aircraft used heavily by Coastal Command as a torpedo bomber and anti-shipping strike aircraft working the Channel, the Bay of Biscay and the North Sea. Carl sortied from East Fortune to build confidence in the Beaufighter. Three weeks later, November 24th, he was deemed ready to go on to further operational training and was granted a week’s leave.

In November, as we can tell from the 415 Squadron ORBs, Manny Niblock was still a supernumerary wireless operator/air gunner and likely able to get leave to join Carl somewhere in Great Britain. We don’t actually know when and where they met overseas, but this seems an opportune time with Carl granted a week’s leave and Manny not yet on continuous operations. Did they meet up in London or did Carl visit Manny down south at Thorney Island? Given the livid scars on his face, the rebuilt jaw and the plastic surgery, perhaps Carl was a little reluctant to go dancing in Piccadilly. I like to think of them meeting up and strolling together in the streets of London or some other city in England, stopping in for a pint somewhere, discussing their situations, the war and their families and looking over the local girls.

After his leave, Carl travelled to RAF Catfoss in the East Riding of Yorkshire, four miles west of Hornsea on the coast of the North Sea on January 12, 1943— a week after Manny’s exciting but fruitless attack on the coastal freighter in the Bay of Biscay. It was here at No. 2 Coastal Operational Training Unit that he would employ his newfound Beaufighter skills to learn the trade of a torpedo and attack pilot. Flying off the three newly-built concrete runways of Catfoss, he would absorb the art, the mathematics and the techniques of torpedo and gunnery attacks on enemy shipping, submarine operations and coastal facilities. Soon he would be in it.

Carl’s and Manny’s lives were working inexorably closer and closer together. They both were part of Coastal Command’s structure by now. Manny’s 415 Squadron began standby strike operations over the North Sea from RAF Docking, Norfolk in mid-January. Docking was only about 110 kilometres south east of Catfoss and Carl, if he had wanted to, could flip down to Docking to visit his friend. Manny possibly had been on flying operations after January 3rd, but the squadron ORB does not record that detail.

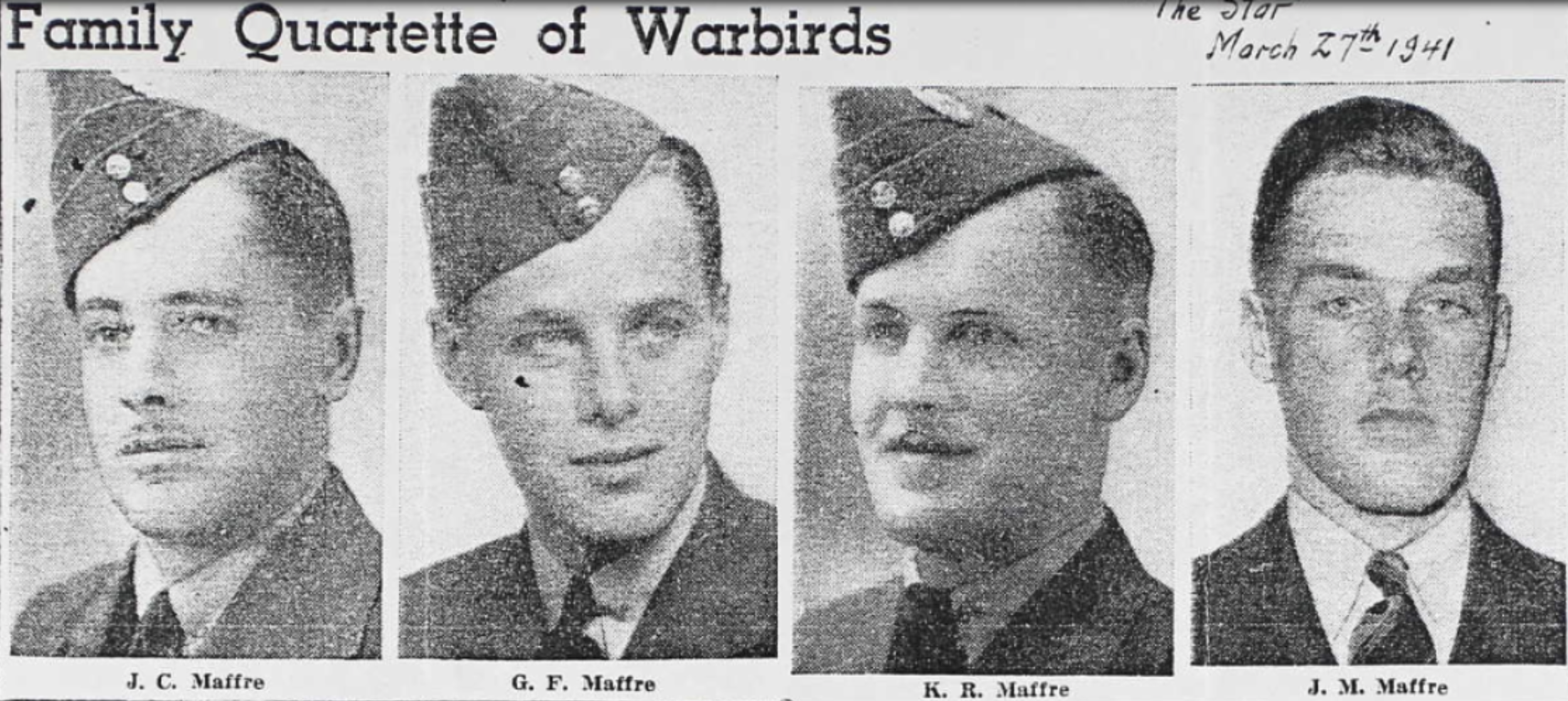

By February, Manny was now part of a regular crew — They were Warrant Officer Paul Brewer Campbell of Arthurette, New Brunswick, the crew’s pilot and commander; Lachine, Quebec-native Warrant Officer Reginald Ernest Vokey who, like Niblock, was a Wireless Air Gunner; Pilot Flying Officer Kenneth Reginald Maffre, the navigator, who was also from the Montreal area and was one of four brothers in the RCAF. The average age of the crew was 22. On the 13th of the month, the took off in Hampden “P” for Peter from Thorney Island at 9:25 PM on a “roaming” mission with instructions to attack any shipping off the French coast. The patrol was carried out in the dark at low altitudes of between 200 and 300 feet. The visibility was fair but the hunting was poor. They landed back at Thorney Island at 1130 that night having spotted nothing.

An English Electric-built Handley Page Hampton TB-1 with RAF serial number AE436 was the next airframe after Niblock’s AE435 on the English Electric “shadow factory” assembly line at Preston, Lancashire. This example was operated by 144 Squadron RAF. The Hampden crashed into a Swedish mountainside in Swedish Lapland on September 5th, 1942. Two crew members managed to walk but the wreckage was not discovered for 34 years. It is present being restored by the Lincolnshire Aviation Preservation Society. Photo: Imperial War Museum

On Thursday, February 18, 1943, 415 was again operating from Docking out over the North Sea. According to the Gorleston Weather Station, to the southwest of Docking, the weather at 6 PM that day was a cold 47˚ F, with very light winds from the North, and hazy with poor visibility (2.5 miles). The cloud deck was at 4,000 feet with 10/10 coverage. Coastal Patrol squadrons rarely enjoyed perfect flying weather.

Typical of flying activity from that airfield, operations were launched after dark. Five Squadron Hampdens were readied with 8 ft. contact-fused torpedoes in their bellies for strikes across the North Sea in search of German shipping off Dutch coast. It was not going to be a good night for the squadron. Hampden ‘S’ for Sugar, commanded by Sergeant A.F. Hildebrandt, was the first to take off took off in darkness at about 6:15 pm on a what the ORB called a ‘Rover Patrol’, hunting for suitable targets to attack wherever they found them. Shortly after take off however, the left engine cowling became loose, rendering the “gills” (cowling flaps) inoperable and Hildebrandt was forced to return to base. As he approached RAF Docking, he was told to hold as there had been an accident.

At approximately 6:39 PM, Hampton “U” for Uncle (GX-U, RAF Serial AE435), a war weary English Electric-built Hampden B-1 converted to a Torpedo Bomber, began its take off roll, long blue flames jetting from the exhaust ports of it two Bristol Pegasus engines. In its weapons bay, it carried an 8-ft long, 18-inch diameter Mark XII torpedo. The weapon weighed over 1,500 lbs. including 388 pounds of trinitrotoluene explosive (TNT). The bomb bay doors had been modified to carry the oversized load on its hangers. As pilot Paul Campbell pushed the throttles to maximum, Manny Niblock sat in his seat at the back of the aircraft facing rearward out through the Perspex of the rear gunner’s windscreen, jostled and bounced by the movement of the Hampden. The noise at the back was almost overwhelming as the two 980 hp engines thundered just ahead of him.

Somewhere down the runway, they reached the point of no return. As Campbell rotated the Hampden, the wheels came off the ground, but something was wrong. They climbed, but not like normal. Then the aircraft seemed to sag, lose flying speed, and drop like a stone in the darkness, Campbell pulling as hard as he could on the control yoke. He struggled along for almost a kilometre. Seconds only. Manny felt it in the back. Paul cursing on the intercom. The dropping sensation. Like being weightless. Then oblivion.

At 6:30 PM local time Hampden “U” for Uncle slammed into the unseen ground next to the Docking Train Station and burst into flames, lighting up the Norfolk night all the way into town. A massive, boiling orange ball of flame rose high into the night sky and was consumed by the darkness. All four young men were killed instantly. There was nothing to be done. Phones rang, RAF fire trucks rolled out of the aerodrome clanging down Brancaster Road toward Docking, guided by the flames. The torpedo had not armed and as a result had not exploded, likely separated from the burning wreckage. Several houses and the station were evacuated as a precaution while armorers from the base arrived to safe the torpedo.

Members of Niblock’s all-Canadian crew. They are Left to Right: Warrant Officer Reginald Ernest Vokey, Wireless Air Gunner; Pilot Officer Kenneth Reginald Maffre, the navigator, and Warrant Officer Paul Brewer Campbell of Arthurette New Brunswick. Images via Canada’s Virtual War Memorial

A diagram of the relation of Docking Station to RAF Docking. The station, the rail line and the airfield are long since gone. Image via Goole Maps

Docking, Norfolk Train Station as it was in 1943 on the West Norfolk Junction Railway. Photo: Docking Heritage Group

The crews of the other three strike aircraft awaiting their sorties were stood down while efforts commenced to find and recover the remains of the four young Canadians. Flying resumed just after 8:30pm when another five Hampdens took off for anti-shipping strikes off the Dutch coast. It continued to be a rough night for the squadron when Hampton ‘O’ for Oboe (P1157) crewed by pilot Alfred B. Brenner, observer Flight Sergeant E.L. Rowe and wireless operator/air gunners Sergeants A. Glass and E.A. Vautier attacked a cargo vessel with their torpedo. Their Hampden was met by concentrated flak from German flak destroyers despite Brenner’s violent evasive action. He headed for home, but, the port engine caught fire and the starboard one began to run erratically, forcing Brenner to ditch the plane in the sea about 30 miles off Yarmouth at about 2300 hrs. The crew scrambled into their survival dinghy and watched their Hampden sink in seconds. Following an extensive two-day search, the four were rescued from their dingy by the crew of a Supermarine Walrus flying boat.

A hundred miles or so south at RAF Catfoss, the recently promoted Warrant Officer Carl Caldwell had no idea that his best friend was now dead and that crews were just then sifting through the wreckage of his smouldering aircraft looking for his remains. It was the end of his day of training and he may have been in his room writing a letter back home or even to Manny. He may have been down to the ancient Dacre Arms Pub in nearby Brandesburton for a pint with his fellow students, or took squadron transport east to Hornsea where there was a selection of public houses to choose from — The Blue Bell, The Rose and Crown or maybe the Ship Inn. Training had been unrelenting now since he left the hospital and he was getting close to being operations ready. He longed to join one of the soon-to-be legendary Canadian anti-shipping squadrons operating along the northwest coast of the United Kingdom. The “Buffaloes” of 404 Squadron were operating from Wick, Scotland and 410 “Lynx” Squadron was at RAF Drem in East Lothian. Both were flying like buccaneers across the North Sea and English Channel, disrupting Nazi supply lines and terrorizing any merchantman sneaking up the Norwegian, Danish and Dutch coasts in convoy.