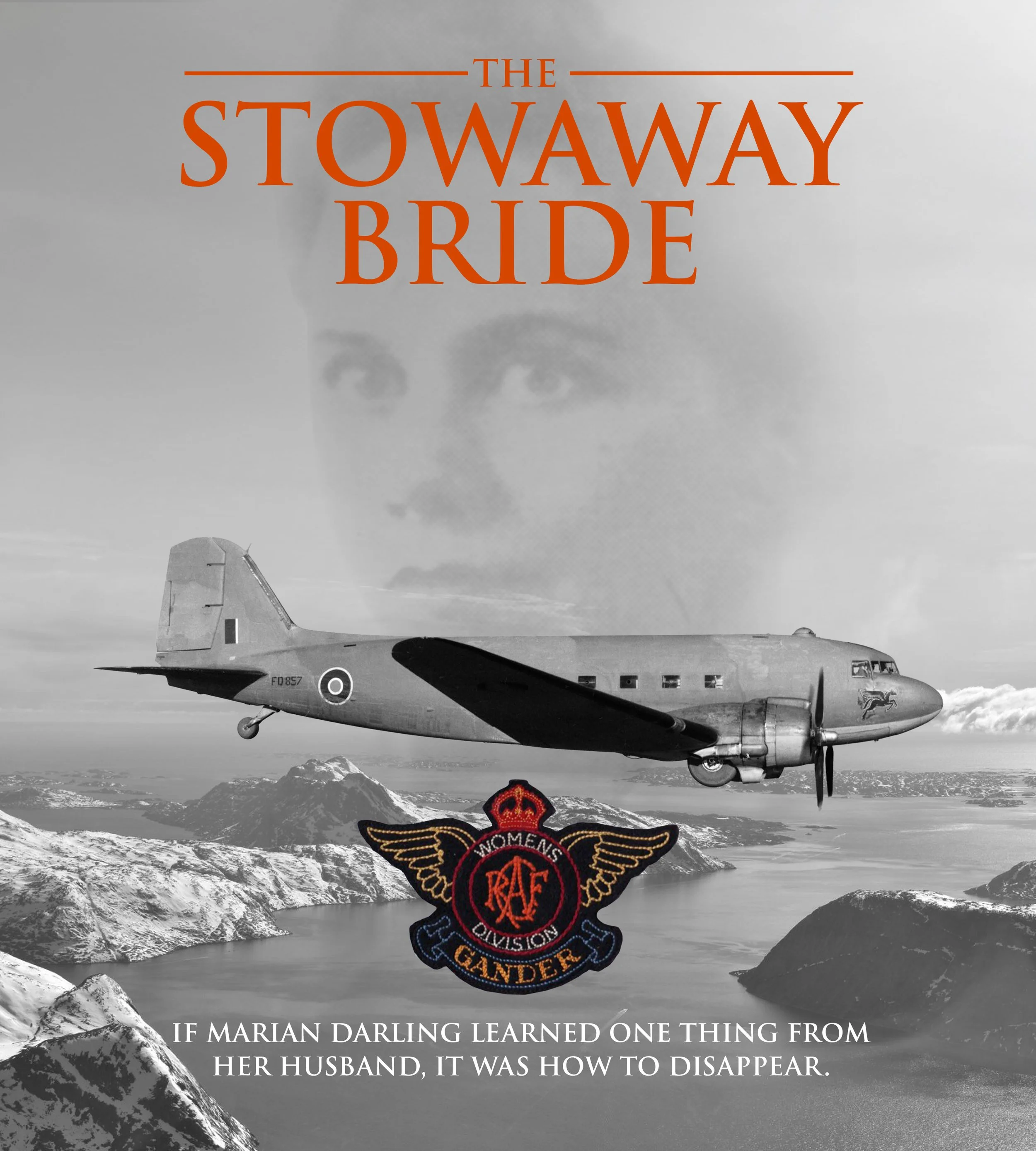

THE STOWAWAY BRIDE

The bones of this story are based on actual facts — dates, times, weather, people, places, newspaper accounts. But it’s fleshed out with dialogue, colours, visions and feelings expressed by me. It is a Valentine’s Day story of love and determination from the annals of Second World War history that played itself out from Ottawa to Halifax, from Massachusetts to Gander, from Scotland to Gibraltar and on into immortality. Here’s to all the wives and lovers whose dreams were dashed so long ago.

February 7, 1943, Two hours west of Prestwick

From the left side window of the cockpit, Captain Nathaniel “Nat” Tooker could see the black-green sea of the North Atlantic Ocean and the endless pattern of pale white breakers and drifting spume flecking the surface all the way to the northern horizon. It always made him shudder looking down on the vast and empty waterscape. “God, If we have to ditch,” he thought to himself, “there is no hope for a rescue in time. None.” Normally he didn't give it a second thought, but just a couple of weeks before, his wife Bette had given birth to their first child — a daughter named Judith Lynne. It gave him a new perspective on his mortality. He would be in Scotland for his first anniversary and he was feeling the distance with every icy mile put behind him. The sky above the lone aircraft was deeply overcast and the morning was a miserable bruise on the eastern horizon, so typical of the North Atlantic in February. The weather was manageable he thought, but the previous two winters had been brutal — high winds, low clouds and the threat of icing conditions all along the Great Circle route from Gander, Newfoundland to Prestwick, Scotland. This would be his 15th delivery flight if the next two hours went OK. Counting his return flights, it was also his 29th trip across the Atlantic Ocean. Just 15 years before, Lindberg had earned himself immortality for just a single crossing. Nearly all the aircraft he had delivered until now were Lockheed Hudsons, but lately there were a few Venturas, Bostons and even a Catalina. By this stage in the war, some ferry pilots had simply vanished out here with their aircraft. Guys he knew. Some on their one and only attempt.

The weather was seasonal when they left Gander—cold and blustery—and they were grateful to get airborne before the predicted sleet and rain. What was left of the cocoa in his thermos was cold and the Spam sandwiches from the Eastbound Hotel had been getting tiresome for months. He was looking forward to a beer and some bangers at the Golf Inn or the Red Lion on Prestwick’s Main Street. There was always a table of ferry pilots, navigators or radiomen smoking pipes, snapping cards, clacking dominoes and waiting for the next Return Ferry Service Liberator shuttle flight back to Gander and Montreal.

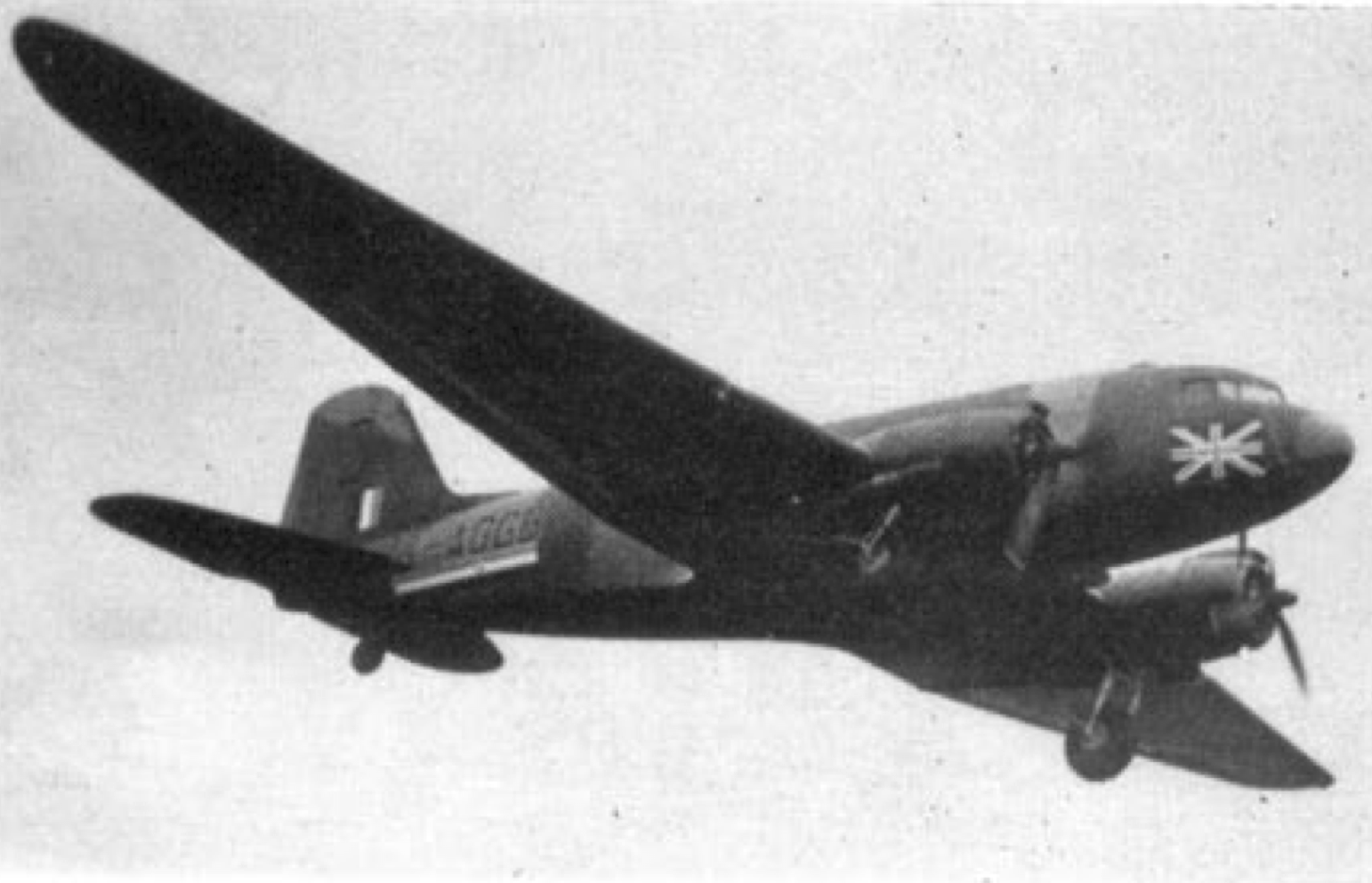

The aircraft he was flying was an American-built Royal Air Force C-47 DL Dakota. He had picked her up in Dorval where it had been delivered by a Douglas factory crew. The DL-suffix signified that it had been built at the Douglas plant at Long Beach, California. And not too long ago! It smelled new, lacked the sweat and oil stains, scuffs and odours it would soon acquire. But everything worked. The snags were few. It had started life as a Skytrain in California just a few weeks ago, but by the time it had been ferried to Dorval and handed over officially to the Brits, it became a Dakota. In the worn logbook in his leather Gladstone behind his seat, he had noted its RAF serial number: FD773.

The two-axis Sperry autopilot worked hard to keep his Dakota steady at 12,000 feet for most of the flight across the Atlantic from Gander, but it wasn’t something he could count on. He had to constantly fiddle with the pitch knob to maintain altitude and adjust the aileron and rudder knobs to keep the aircraft on track, especially in windy conditions. And this environment was all windy conditions. It was supposed to alleviate work, but there was no way he could doze.

He preferred it here at the lower altitudes. He didn’t have to use the oxygen and the guys could smoke to while away the more than eleven hours they had already drilled through the night sky and on into the grey morning ahead. The icing was less of a problem down here too, though the “Dak” had accumulated some rime over the past hour or so. It was manageable. Beside him was another American, a Kentuckian named Burton Craig Miller. Like him, Burt had been a civilian pilot before the war. With their experience, neither man wanted to go through the restart and rigamarole of training required to become an RCAF pilot, when they could contribute immediately… and get paid better. And frankly, the risks were higher in the RCAF. Even after the United States joined the war, they were too seasoned to start over.

This was the way they were contributing to the war effort. Maybe it was for the Brits, but they were Allies. Many of the RAF’s Liberators, Mitchells, Catalinas and Havocs were getting to the war this way… across the North Atlantic. He could see them parked wingtip to wingtip at Gander or Prestwick every time he landed there. His job was dangerous, but at least no one was shooting at him. It wasn’t much different from his work as an American Airlines pilot before the war.

Burt and he took turns kipping while the other monitored, stretched and yawned. So much yawning. Like his previous flights, the night had been long. Not enough to do. The cold starting to creep in. The engines roaring hour after hour but somehow unheard… unless their sound changed. Even the slightest perceived fluctuation in the tone had them sitting bolt upright, ears cocked, eyes darting across instruments, head straining to look back along the wing. Then the engines would settle down again. And the adrenaline would carry them through the next thirty minutes or so. Staying awake was the problem. The roar became a drone. The drone became a lullaby.

John McIntyre, the wireless operator, sat behind the cockpit bulkhead on the starboard side. He was from Kingston, Ontario and had even less to do throughout the night. They liked to keep radio silence as much as possible. Communication was typically restricted to essential, encrypted messages or periodic position reports. These former civilian Canadian Pacific (CPR) and ATFERO (Atlantic Ferry Organization) radio guys had deep experience with navigation and direction finding as well. Once 45 Group of Ferry Command took over the massive RAF North Atlantic ferry operation, a lot of those guys stayed on. To do their bit. He came forward now and then to chat, but he spent most of the flight isolated behind the bulkhead. At least he could rest his head in his arms at his table on the starboard side. He liked to stay on top of the navigation too just as back up, and soon, as they approached Scotland, he’d have his radio work to do.

But they didn't just rely on Radio Officer McIntyre to get them the two thousand miles across the ocean, past Islay and Arran and into the Firth of Clyde. There was a dedicated navigator aboard as well — J. R. Fraser. Fraser was one of the many old school civilian navigators employed by Ferry Command. Fraser and McIntyre had been there since Gander first became operational in November of 1940. Though everyone in Tooker’s crew was a civilian, they were all highly-experienced and well-seasoned on the North Atlantic ferry route, having flown ferry operations under CPR management long before ATFERO and now under RAF Ferry Command which had taken over the ferry operations between Canada and the United Kingdom. A month from now, the organization would change yet again — coming under the control of Transport Command with a reduction to group status (45 Group).

Around 6 AM, Gander time, and eleven hours into their flight, Miller unbuckled, stood up, stretched his back out and told Nat he was going to the head and to get his jacket. They had stowed their winter greatcoats, extra flying gear and luggage in a pile at the back of the cabin next to the toilet bulkhead. He tapped the shoulders of McIntyre and Fraser as he went by them and into the dimly-lit volume of the cabin, lurching down the centre between the seats that lined the fuselage walls, towards the head.

Ten minutes later, Miller leaned through the cockpit doorway and tapped Tooker on the shoulder. “You’re not going to believe this Nat”

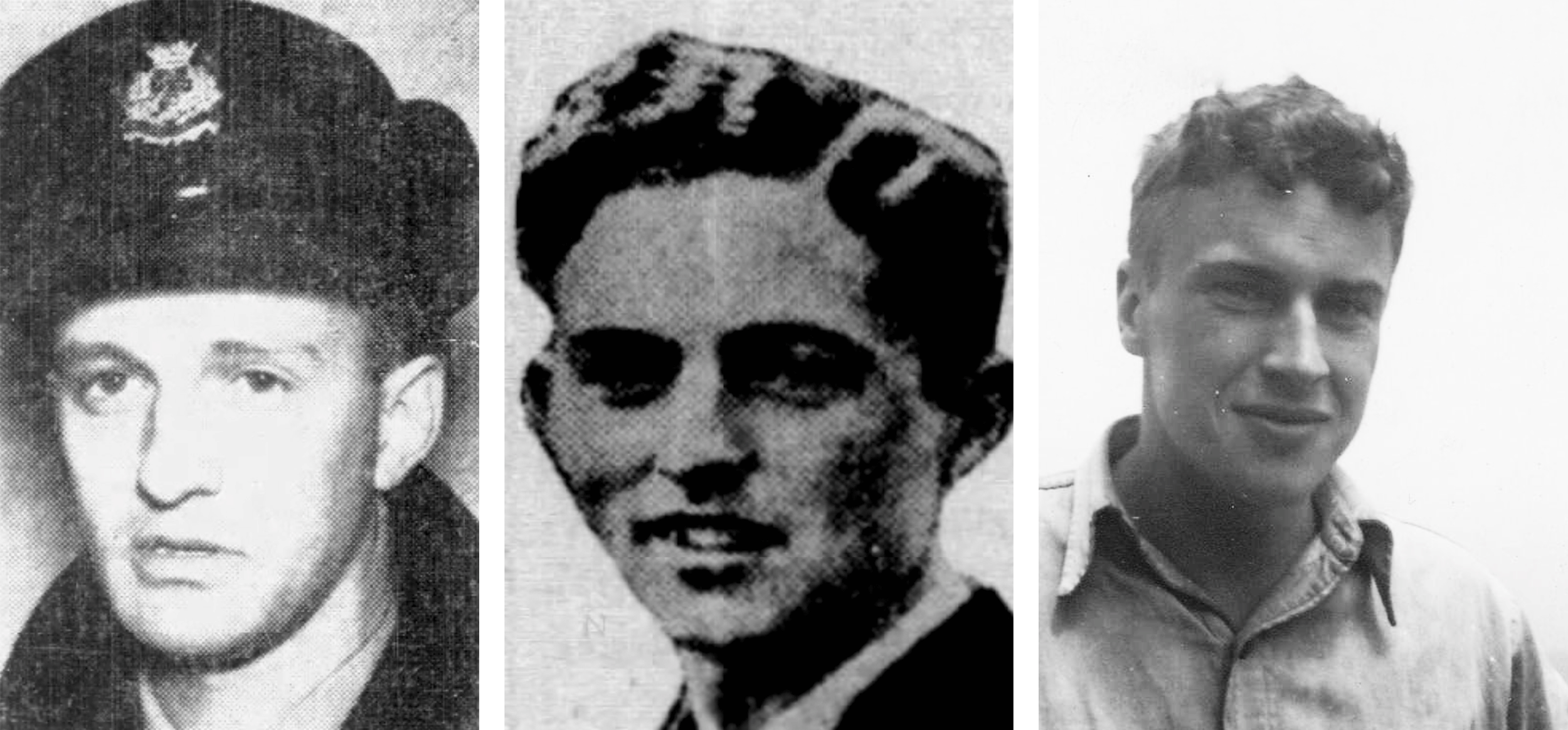

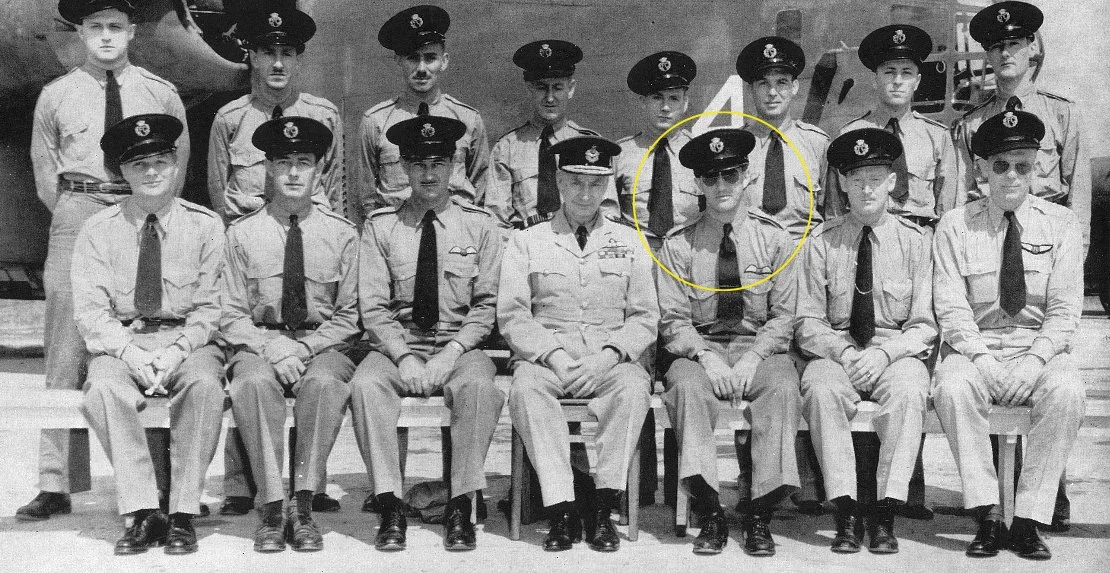

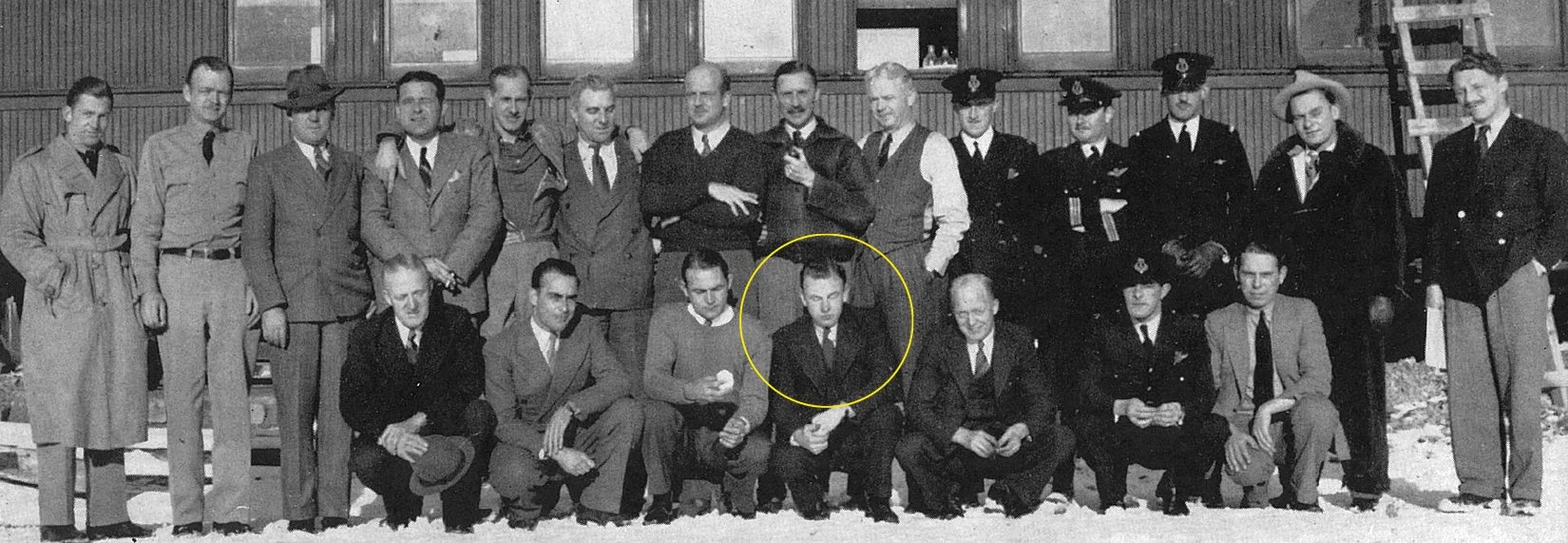

The Crew of Douglas C-47 FD773

The crew of Dakota FD773 (Left to right): Aircraft commander: Captain Nat Tooker, a pilot and parachutist before the war. He went to high school in Kuling, China where his father was a missionary; Co-pilot: Captain Burton Craig Miller, also a civilian pilot before the war and Radio Officer John Donald McIntyre, all civilians. Neither Miller nor McIntyre survived Ferry Command and the war. Burt Miller was killed a few months later along with the ferry crew of a Martin Marauder near Puerto Rico and McIntyre was killed almost two years to the day later in the crash of a Canadian-built de Havilland Mosquito near Amherst, Nova Scotia (the Mosquito parted with a wing following a dive). Photos: Tooker, newspapers.com; Miller and McIntyre: CASPIR

Let’s leave the crew of FD773 high over the Atlantic to deal with their “discovery” and travel back in time to Ottawa, Ontario and take a look at the life of Gordon Johnston Darling, a young man from the city’s Glebe neighbourhood whose story is directly connected to the events of February 6-7, 1943.

As with so much of Ottawa’s Victorian past, the buildings of Gordon Darling’s young life no longer exist. Darling came into the world at Ottawa Maternity Hospital (right) at the eastern end of Rideau Street in Ottawa. While it looks like a posh home of one of Ottawa’s lumber barons, it was purpose-built for $18,000.00 as a maternity hospital—perhaps to provide mothers a sense of homeliness. The ladies in attendance at its opening in 1895 were the wives of the who’s-who of Ottawa’s most important leaders — Bronson, Ahearn, Topley, Mutchmor, Wright, McNab, and Lady Aberdeen the wife of the Governor General. Darling attended Borden Public School at the corner of Powell and Bronson Avenues a couple of blocks from his home. Both structures were later demolished to make way for apartments and condominiums.

Gordon Darling was born on April 2nd, 1914 at Ottawa Maternity Hospital on Rideau Street. His parents were the newly-wed Alexander, a stationary engineer for the City of Ottawa and native of Parry Sound, Ontario, and Mabel (née Johnston) Darling of 333 Powell Avenue in what today is called The Glebe Annex, then a working class adjunct of the more upscale Glebe neighbourhood. After Mabel delivered the child, Alex called the Ottawa Citizen and Ottawa Journal with the news and paid 25 cents for birth announcements (death announcements were 50 cents!). The family would move within a few months to a new home at 375 Carling Avenue where Ottawa’s most important east-west road rose from Dow’s Lake to the higher ground beneath Bronson Avenue and then move again, in his high school years, up the hill to 273 Carling Avenue.

From 1920 to 1928, he attended Borden Public School at the corner of Bronson and Powell Avenues for his elementary education and then Glebe Collegiate Institute from 1928 to 1934 for his secondary education. Glebe Collegiate was literally a stone’s throw from his front door on Carling Avenue. During his years at Ottawa’s newest high school (it had officially opened in 1923) he made his grades without any outstanding results but played sports with utter abandon. He was a member of the 1930 Eastern Ontario Championship Glebe Gryphons rugby football team and picked up skiing at Camp Fortune in the winter months. He enjoyed plenty of other sports as well including swimming, tennis, softball, track, hockey, basketball, and golf. He had glorious, flowing and expressive handwriting which he clearly enjoyed flourishing.

At the beginning of high school (and after his 15th birthday) Gordon enlisted in the Canadian Army Reserve, joining the 2nd Field Battery of the 1st Field Brigade of the Royal Canadian Artillery and trained as a gun layer. At 5’-7 1/2” and a mere 114 lbs, he certainly was a boy soldier. He left the artillery in 1930 and then, a few years later in 1933 as he was finishing up high school, he re-enlisted in the 3rd Division Signals of the Canadian Army. By now, he had grown two inches more in height and now weighed 144 lbs— the typical physique of young men in those days before growth hormones, refined sugars and fats. In his attestation papers for this enlistment, it is interesting to note that under nationality he did not write “Canadian” but rather two letters: “BS” for British Subject. The connections to Great Britain were still strong for young, white, presbyterian men in the years between the wars. Upon enlisting, and due to his former militia rank of Lance Bombardier, he was made a Lance Corporal, but six months later on Boxing Day, 1933, he had done something that caused his demotion to “Signalman”, which was a buck private in the signals divisions. It was an early indication of his unconcern for regulation.

The Glebe Collegiate Institute Gryphons junior rugby football team in their blue and gold uniforms pose in November of 1930 in front of their school building with 16-year old Gordon Darling sitting at left. They had just beaten a team from Pembroke in a sudden-death play-off. This qualified them to play against Kingston Collegiate in the Eastern Ontario Secondary School Athletic Association (E.O.S.S.A.A) football final at nearby Lansdowne Park. Darling played outside wing in this, his first year of collegiate rugby football. They won the game 15 to nothing.

Following high school (according to Attestation Papers he filled out upon joining the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) a few years later, Darling enrolled in a general science program at Clarkson College of Technology (now Clarkson University) in Potsdam, New York in 1934 and remained there until 1936. Strangely, I can find no mention of him in any “Clarksonian” year books available online from New York Heritage. These year books listed every student at the college and included photos, but Darling is nowhere to be found — at least in any of the year books from 1932 to 1937. Perhaps he was taking a correspondence course, though I can find no evidence that these were offered. Young Gordon Darling was becoming a mystery to me. He also claimed on the same Attestation Paper that he was again with 3rd Division Signals from 1936 to 1937, this time with the rank of Subaltern—a primarily British military term for a junior officer. Literally meaning "subordinate", subaltern is used to describe commissioned officers below the rank of captain and generally comprises the various grades of lieutenant, especially Second Lieutenant. On reviewing his Statement of Services in the Non Permanent Active Militia of Canada however, there is no indication there that he served as a junior officer nor is there evidence in his online service file. The same file states he was struck off strength with the 3rd Division Signals in April, 1934.

The Elmwood Apartments on Barrington Street.

In 1936, after returning from Potsdam, Darling was caught speeding on Bank Street in Ottawa. He was fined $10 plus $2 court costs and had his driver’s license suspended for ten days. He had been caught driving 25 mph over the 20 mph speed limit, an offence today that is considered stunt driving in Ontario. Although certainly not a crime, it was a harbinger of Darling’s penchant for testing the rules in his future military career. Luckily, he could afford to pay the fine now as he was employed in the chemistry laboratory at J. R. Booth Ltd, a massive lumber mill and pulp and paper company mainly situated on the Hull, Québec side of the Ottawa River.

His work at J. R. Booth lasted only two years after which he resigned in 1938 to take a position with the Industrial Acceptance Corporation Ltd. (IAC) in Halifax, Nova Scotia. IAC was a prominent Canadian finance company specializing in installment financing, particularly for automobiles and other consumer durables, acting as a crucial intermediary for consumer credit during the Great Depression. His job title was “adjuster” and he continued to work and live in Halifax for the next three years. He lived in a small apartment (No. 5) at the Elmwood Apartments on Barrington Street close to the busy waterfront.

At one point in the summer of 1940, Darling found himself in Springfield, Massachusetts — perhaps on business. While there, he met a 23-year old American nurse by the name of Marian Elizabeth Bowers. According to Darling’s sister Audrey, Marian was “very attractive, blonde and of medium height and weight”. The press would later describe her as having “big appealing eyes and a fragile daintiness”. Marian had been raised in Springfield, attending Classical High School in Providence, Rhode Island and then studied nursing in New York City. She was a registered nurse in New York State. The powerful attraction they had for each other would, I believe, drive them both to extremes to see each other despite geography and circumstances.

By late 1940, Darling was perhaps moved by the scenes of convoys and escorts coming and going from wartime Halifax Harbour, the Narrows and Bedford Basin. The activity was round-the-clock and sailors of all nationalities—military and merchant marine—were everywhere in the city. Whatever his motivation, in October he walked into the recruiting office and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy.

He was given a cursory medical examination which revealed he was still growing — 151 lbs, and 5’-9 1/2”. By November, there was a note on his Certificate of Medical Examination which stated that he was “in Officer’s Training Class and would be attested shortly, but won’t be on pay until called up for Active Service Duty”

Unfortunately, he was not the only young man from the Maritimes or across Canada who wanted to join the navy. He received a form letter on November 13th from Naval Secretary to the Commanding Officer of Halifax Barracks stating:

“I am directed to acknowledge with thanks your offer of service and to state that your patriotism is appreciated.

It is regretted that you cannot be offered immediate entry, but the number of applications received far exceeds the vacancies available. A Naval Service of necessity grows slowly.

Your name has been noted on the list of volunteers, and if a suitable opportunity occurs to use your services, you will be notified. As already explained, the expansion is slow and you may not be called for a considerable period.

It will not be necessary to repeat your application, as your name will not be overlooked when an opportunity of using your services arises.

Should you, in the meantime, join any other of the Forces, it is requested that you will inform this Department in order that your name may be removed from the Naval Volunteers’ list.

Though Darling was provided with the $20.00 per month allotment (in February, 1941) due a Sub-Lieutenant In the Royal Canadian Volunteer Reserve, he was not yet in the Navy. By December 12, 1940 he had attested and his papers noted that he was now 152 lbs. and had miraculously grown an inch in a couple of months to 5’-10 1/2”! Despite having begun the process of enlistment in the Royal Canadian Navy, impatience likely got the better of him and he resigned from the IAC and took a job in Ottawa with the “British Supply Board in Canada and the United States” (BSB — an offshoot of the British Purchasing Commission) as an examiner of steel forgings. It managed vast procurements, including munitions, vehicles, and ships, eventually merging into Canada's Department of Munitions and Supply.

By July of 1941, Darling had grown tired of waiting for a call-up to the navy reserve and after a medical and an appointment with the recruiting officer for the Royal Canadian Air Force in Hamilton, Ontario, signed his attestation papers on July 23rd. He dropped rank from probationary Sub-Lieutenant to Aircraftman Second Class (AC2) and lost his $20 monthly allotment from the navy. Perhaps the reason this was done in Hamilton was because he was there to inspect steel forgings in one of the many steel factories in the great industrial city. A month later, while filling out his Occupational History Form at No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto, Darling claimed to have been living in Hamilton at the time of his enlistment.

The interviewing officer offered his opinion on Darling: Very good type of mature Canadian. Well educated and experienced in service life. Keen to serve and fly and also to redeem himself and should do well in training. Just why the officer thought Darling needed redemption is unclear.

Manning Depot was Darling's first step on his journey to become a fighter pilot. It was the place where raw recruits learned to “be air force” with courses on military regulations, care of uniform and kit, firearms training and plenty of marching and other forms of drill. He likely aced his Manning Depot tests as he had been a Lance Bombardier and Signals private before the war. His General Conduct Sheet was unblemished in Manning Depot, but that would change in time.

Darling left Manning Depot on August 20th and was taken on strength at No. 5 Initial Training School in Belleville, Ontario within the week. Here, he took on a heavy workload of courses in the fundamentals of navigation, signals, armaments, aircraft recognition, aerodynamics as well as courses in meteorology and mathematics, all designed to find the best candidates for pilot or navigator training. Anyone who did not make the grade was shunted off to radio, gunnery, bomb-aiming or flight engineering training. On emerging from Initial Training School, Darling’s assessment was very good: “Excellent type Canadian lad, good sound spirit. Excellent pilot navigator material. Commission material.” He was selected for pilot training and on the morning of October 27 along with several of his classmates, found himself at the gate of No. 13 Elementary Flying Training School outside the rural Ottawa Valley village of St. Eugène, Ontario. Collectively, they would be known as “Course 41”.

At No. 13 EFTS in St. Eugène, Ontario, Darling learned to fly the Fleet Finch trainer. Photo: RCAF

Flight Risk

Two weeks after his arrival and the commencement of his basic flying training on the diminutive Fleet Finch biplane trainer, Darling had his first foray into the world of Absence Without Leave (AWOL) when he disappeared for about 40 minutes sometime after 10:30 PM on a Tuesday night. (enough time to walk to St. Eugène, make a collect call to Massachusetts and return — just saying). It was by most standards a minor infraction and he was admonished and given a slap on the wrist.

Two weeks later on December 5, 1941, he ramped up his disappearing act when he went AWOL again, this time for eight hours, leaving again at 10:30 PM on a Friday night, but not returning until 06:30 AM on the following Saturday. This time, he forfeited a day’s pay and had to spend each night of the following week washing aircraft in the cold and drafty St. Eugène hangars. One wonders what exactly he did for those eight hours. Had he and Marian had a tryst in Montreal or Ottawa? Or had she taken the train to nearby Hawkesbury?

Regardless of his spotty behaviour during his time at St. Eugène, he graduated among 34 others who had successfully completed Course 41. One of his classmates had failed ground school, five failed progress tests, six failed their 20-hour test or 30-hour rechecks and one made it all the way to his 50-hour check before his training was ceased. Despite the attrition, it was one of the largest graduation classes since the school opened and the Operations Record Book notes that “There was a larger number of above average pilots than usual.”

Darling was assessed as “A good student, tried hard to improve and general flying became good, but he passed a poor 50-hour test. Inclined to be nervous when with another instructor than his own, Instrument average.” Despite his poor 50-hour test result, he did not “cease training” like his fellow student pilot. Though previously considered commission material, he was now considered “unsuitable”

Having passed the elementary flying stage of his pilot training, Darling and the others of Course 41 were bussed by government transport en masse down the old Highway 17 to Montreal and then across the St. Lawrence River to RCAF Station St. Hubert. This was the home of No. 13 Service Flying Training School, the next ,and more advanced phase, of flying training. The 35 pilot trainees from St. Eugène joined others coming in from Quebec bases like Windsor Mills in the Eastern Townships and north shore stations like Cap-de-la-Madeleine and L’Ancienne-Lorette to become collectively “Course 45”. In all, there were 69 students who started the course on December 22nd, but there were far fewer three months later when the course graduated. The aircraft used at this stage of his training was the robust and powerful North American Harvard (Texan in America), the most ubiquitous advanced flying trainer used by the Allies in the Second World War.

The North American Harvard was the mainstay of advanced single-engine training in Canada throughout the war and for twenty years after. Photo: RCAF

With a month left to go on his course, Gordon Darling went missing on February 13, 1942. He would be gone long enough that he was declared a deserter by the Provost Marshal. He would not return for 17 days and three hours, but did so of his own free will, showing up at the station guardhouse on Tuesday, March 3rd at 8 AM. He was immediately arrested and detained for the next 21 days. As well, he forfeited 18 days pay, equivalent to his time on the lam. His class had their wings parade on March 11 and received their postings, while Darling cooled his heels in the brig. Given the severity of his misconduct, it is a wonder that he was allowed to restart his flying training after his release. As it was, he joined Course 51 and started over again. While AWOL is considered simply missing, desertion implies an intention to never return, or to avoid dangerous duties (like deployment). Darling would have been charged with desertion if he had been absent over 30 days, but personnel who returned voluntarily to military custody after a long period avoided the stigma of desertion and were usually processed out of the service. Quite the opposite for Gordon Darling.

Given the intensity of their love affair and the extremes Marian Bowers would soon go to to see her man in Great Britain, the most likely reason I can think of for his three week absence is that he and Marian were holed up somewhere doing what young lovers do. According to some later newspaper accounts, Marian was living in Montréal in 1942.

Just two weeks after his release from detention, however, he found himself in trouble again. On a Saturday night in April the Montreal police picked him up at the corner of St. Urban and Dorchester Streets for disorderly conduct, likely brought on by excessive alcohol. He “was in a disorderly condition and riding a purloined bicycle” according to the constables. In addition, he made matters worse by offering a false name and service number to the RCAF Service Police who came to take him in. For this, he went back to the brig for two more weeks. Again, upon his release, he was allowed to continue his training.

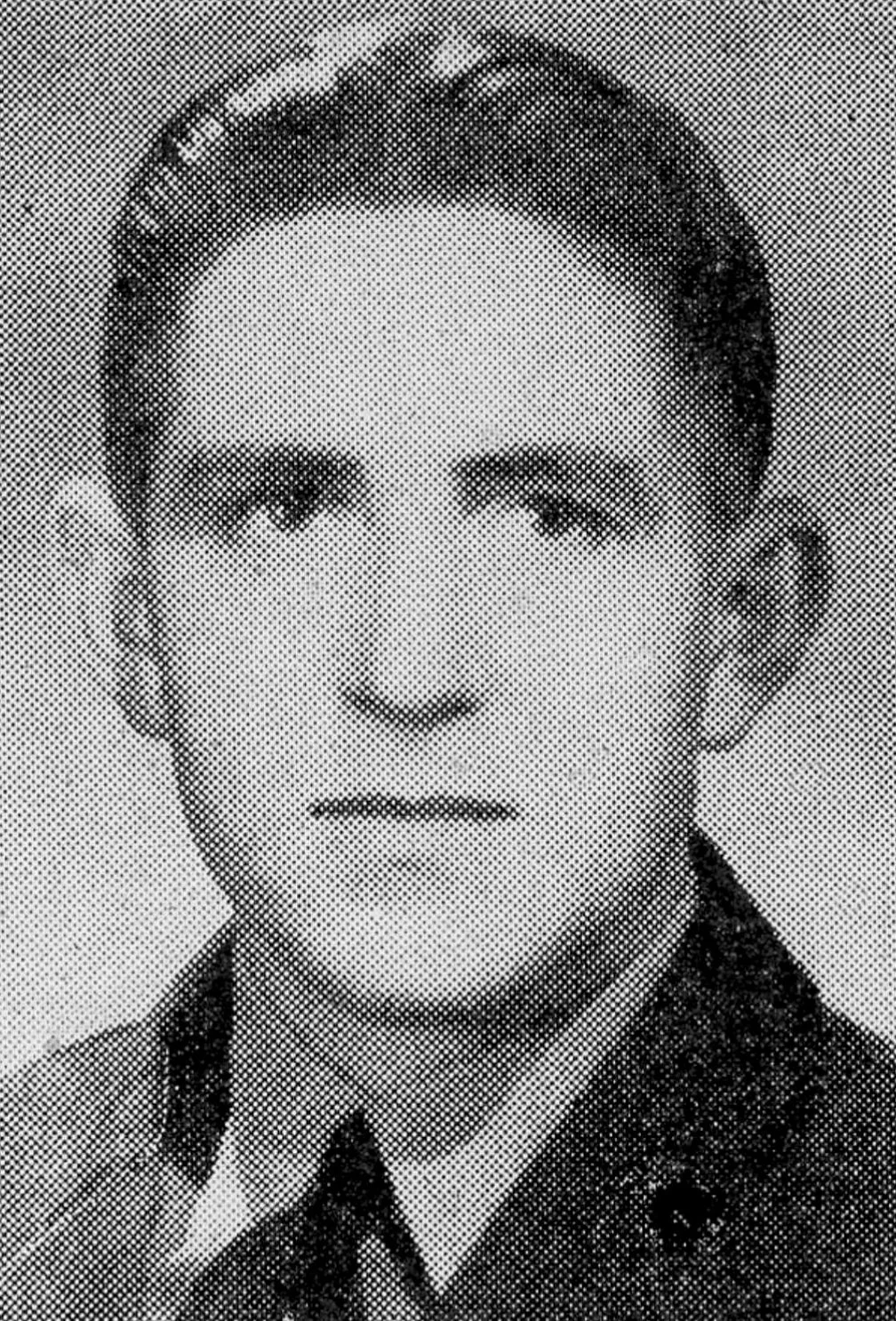

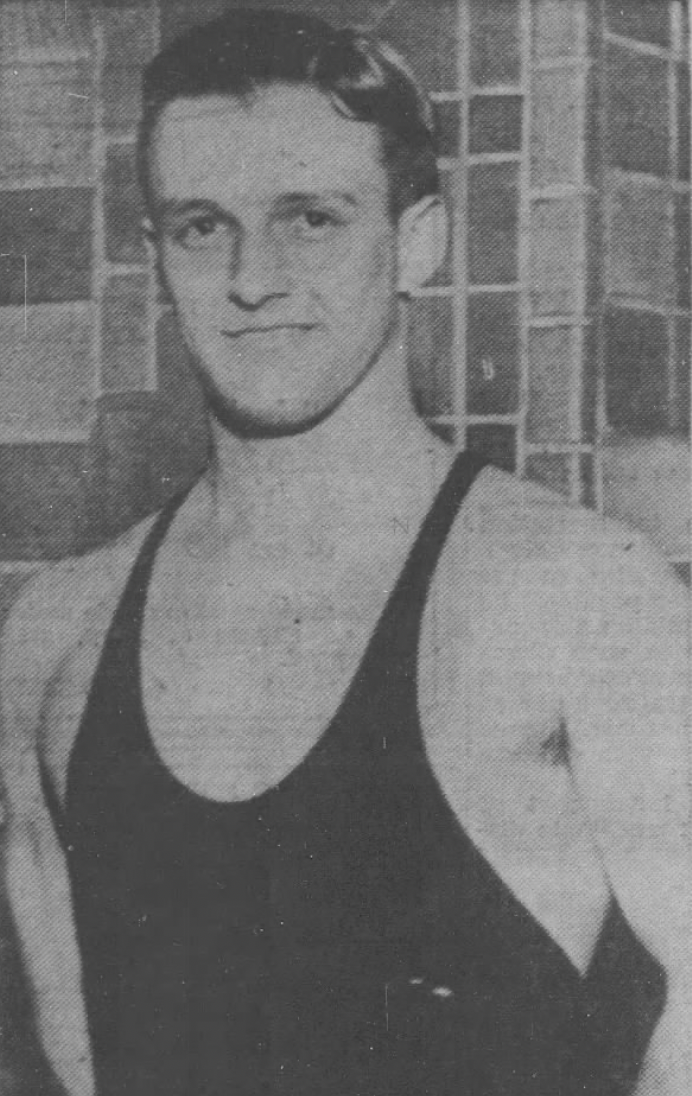

Sergeant Gordon Darling poses for a studio portrait after earning his pilot’s wings on Dominion Day, 1942. Image via Newspapers.com

While Darling was completing his training, one of the worst training accidents in British Commonwealth Air Training Plan history took place at St. Hubert, or rather the tragedy began there. Eleven North American Harvard training aircraft from “G” Flight” took off from St. Hubert at about 9 PM for a nighttime navigation training flight to RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa and back to St. Hubert via Alexandria, Ontario. Each aircraft included a student and an experienced instructor. After arriving at Rockcliffe and turning for Alexandria, they ran into poor weather. Seven of the aircraft broke away and returned to St. Hubert individually, while the others, flying together, got disoriented after passing over Alexandria and flew across the St. Lawrence River at the wrong place. Shortly after, at around 11 PM, they flew in bad weather into the Adirondack Mountains at Ragged Lake near Malone, New York. All four Harvards impacted the ground, killing three of the two instructors and one student. Two others were seriously injured while the remaining three were slightly injured. Within a week of the accident, three students ceased training at their own request (one because of “nervousness”) — an uncommon occurrence.

I have reviewed many RCAF service files and enclosed General Conduct Sheets over 20 years of research. Rarely, if ever, do I find offences greater than the wearing of a great coat unbuttoned or the busting of curfew. It’s astonishing to me that Darling was allowed to continue training and eventually to become a fighter pilot. Perhaps it had something to do with his flying ability. In late June that summer, his Squadron Commander, Flight Lieutenant Mongeau wrote: “Flying ability high average, Intelligent but very poor on discipline [You think? — Ed]”. The Chief Ground Instructor added redundantly that he “needs discipline, intelligent. Missed a good part of ground school, but succeeded in passing ground school.” Then again at the end of his course after finally receiving his pilot wings on Dominion Day, 1942, Wing Commander A. Watts, the school’s Chief Instructor summed the two sides of his character very well: “This pupil was below average in discipline. Should be watched. Has high average flying ability.” Perhaps they realized that these were the two traits they were looking for in a fighter pilot.

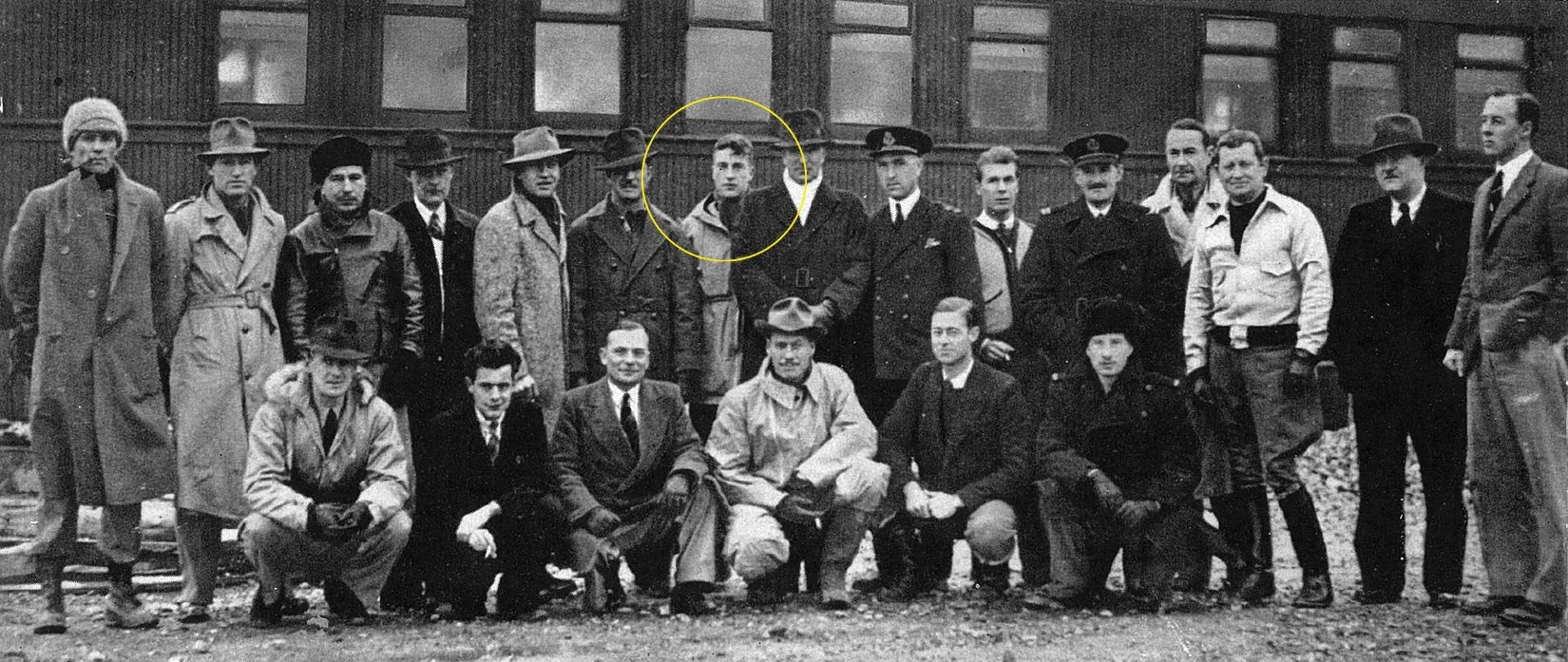

Leading Aircraftman Gordon Johnston Darling had his wings pinned on him on the ramp outside one of the hangars at No. 13 SFTS on Canada Day, July 1st, 1942. Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Bowhill (of the magnificent eyebrows), British Officer Commanding RAF Ferry Command was on hand to deliver an “appropriate” speech and pin the wings on the graduating class. Because of the auspicious date, the wings parade included two flights of Air Cadet Officers in training at St. Hubert as well as an exhibition of formation flying during the ceremony. Thirteen of the graduates were posted to flying instructor schools in Trenton and Arnprior. Being posted to flight instruction was considered a punishment by students eager to get to the war or at least an undesirable outcome. Darling, who had done so much to warrant expulsion from the course, was one of 18 students posted to overseas operational training on fighter aircraft.

Newly-winged Sergeant Gordon Johnston Darling was promptly posted to ”Y”-Depot in Halifax as of July 27, there to await passage to Great Britain for operational flying training. But having just completed a year of training and receiving his pilot’s brevet, he was entitled to (but perhaps not deserving of, given his absences) Embarkation Leave to visit loved ones. There is no record of whether he returned to Ottawa to see his family, but on the 27th, he was in Halifax as ordered and he filled out his Statement of Embarkation declaring he was single. Four days later, he and Marian were married in Halifax by Flight Lieutenant W. M Rodger, a united Church of Canada Chaplin in the RCAF. Gordon’s best man was Bruce Edward Pinch from Thornbury along the shores of Georgian Bay, Ontario who had graduated as part of Course 51 along with him. Marian’s bridesmaid was a woman named Flora Doremus Wilder, a fellow American from Bogota, New Jersey. Flora was married to another classmate of Darling’s Course 51, Burton Eastman Wilder, also an American.

[A note about the spelling of Marian’s name. In almost every newspaper account it is spelled with an “o” as in Marion. Even newspaper accounts who spoke directly to Marian and her family. Her simple headstone on the Oak Grove Cemetery also reads Marion B. Lidstrand, but I have gone with the spelling given in 1920 American census, on the certified copy of their marriage certificate found in Gordon’s service file, the Statement of War Service Gratuity Form from in the same file (an amount of money to be granted the recipient following their spouse’s or child’s death, based on the totality of the airman’s service — in this case, $245.88), her husband’s Record of Service Form R230 and her husband’s Death Certificate. Unless, of course I am quoting newspapers that used “Marion”. I suspect she accepted use of both spellings]

A week later, after Darling bid farewell to his new wife, he joined Bruce Pinch aboard a troop ship for the voyage across the North Atlantic. They disembarked in Liverpool and made their way to No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre (3 PRC) in Bournemouth, arriving there on August 19 to be processed by the RCAF and posted to further training.

The only image of Marian Elizabeth Bowers to be found online. Her large eyes framed by delicate features command your attention and did so for many newspaper writers in 1943. Image via Newspapers.com

It appears that just two days before her wedding, Marian decided to join the Women’s Division of the RCAF, perhaps with the hope of finding her way to Gordon. After Darling shipped out from Halifax, she trained at No. 7 Manning Depot, the all-female manning centre at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa. Here she learned the same basics as her male colleagues (King’s Regulations, Drill and Discipline) but also etiquette. All later reports in the newspapers would list her as a Leading Aircraftwoman or simply a member of the Women’s Division (or WDs for short). Some would call her a nurse, but all RCAF nurses were members of the Medical Branch and not the Women’s Division. Those women were considered officers and were ranked as Nursing Sisters. We know Marian did not join the Medical Branch, but rather the Women’s Division. The only “medically trained” women working in the Women’s Division were Hospital Assistants. In Gordon’s Record of Service Form she is listed under the heading of “Persons to be Informed of Casualties” as an AW1 (Aircraftwoman First Class) along with her Women’s Division service number (W306321). Perhaps Marian took a demotion in status to accelerate her advancement in the Women’s Division, perhaps hoping to be posted overseas.

After graduating from Rockcliffe, a process similar in timeframe to the airmen’s requirement—4-5 weeks— Leading Aircraftwoman First Class Marian Elizabeth (Bowers) Darling was posted to St. Thomas, Ontario, the home of the RCAF’s No. 1 Technical Training School. Located at what is now the St. Thomas Psychiatric Hospital complex, the school trained ground crew for active service and all types of lower echelon roles. It accommodated over 2,000 students at a time, teaching courses to airmen in airframe, aero engine, instrument mechanics, and fabric/sheet metal work. They also taught members of the Women’s Division in administration support, radar and wireless operation, photography, photo interpretation, parachute rigging, instrument repair, and most importantly hospital support, which is very likely what she was doing there. One group of 12 Hospital Assistant graduates that fits Marian’s timeframe had their graduation parade on October 20th, 1942. The top graduate noted in the school’s Operations Record Book, WD.2 J. R. MaCrea, is the only one noted, but her service number (W306376) was very close to Marian’s WD306301 which leads me to believe they possibly came from No. 7 Manning Depot together.

Despite the difficulties in tracking down the exact dates of Marian’s service with the Women’s Division, which would require pulling her service file from Library and Archives storage, we know that around the end of 1942, she found herself in Gander Newfoundland posted to the massive Ferry Command base there. She was now as close to her husband as she could get without crossing the Atlantic.

Meanwhile in England

When Gordon Darling arrived at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre on August 19, he got settled in and processed and then the next day cabled Marian that he was safe and sound in Great Britain. Airmen being processed at 3 PRC were billeted at a number of small hotels in the city. His stay here was to be just ten days until a spot could be made for him at an Advanced Flying Unit to refresh his flying skills and to get ready to fly fighter aircraft. Though he was here for a short time, he wasted no time in getting into trouble. Just two days after cabling Marian, he disappeared once again, failing to appear at the daily parade at 13:43 hrs on the 22nd and the 23rd. For this he was reprimanded and forfeited another day’s pay. Perhaps if his General Conduct Sheet had followed him, they may have been a little less lenient.

Darling likely enjoyed the brief stay at the seaside town of Bournemouth, relaxing at the beach, drinking beer and gin in the hotel bars. There was little to do in the way of Air Force work, just show up for the daily parade, which, it seems, he did when he felt like it. On the 29th, he was struck off strength at 3 PRC and received a travel voucher for the day-long train journey on the Southwestern Main Line to RAF Watton in Norfolk, some 320 kilometers to the northeast. Here he would join No. 17 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit (17 AFU). What an exciting train ride that must have been— the smoke-filled carriages rattling and jostling through villages and market towns so different from Ottawa — Sway, Brockenhurst, Southampton, Eastleigh, Winchester, Basingstoke, Woking and on into London’s Liverpool Street Station to change trains, then Cambridge, Little Thetford, Ely, Littleport, Downham Market, Stowbridge, Watlington and on into King’s Lynn where he detrained to await transportation to Watton — about 35 kilometres to the southeast.

The Miles Master trainer was used by 7 (P) AFU to bring pilots up to speed again following the month since getting their wings. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Upon his arrival at Watton, he was assigned accommodations and provided with the flying gear he would need (helmet, parachute, gloves etc.) to begin his training. The aircraft he would be flying was the Miles Master, an aircraft with a similar role to the North American Harvards he flew at St. Hubert. Pilots found the controls, particularly the ailerons, to be light and effective, offering a true fighter-like feel during training maneuvers, but the Master was known to be somewhat unforgiving; it required careful handling at low speeds, as aileron drag could induce a spin during a stall. His flying began with dual instruction provided by an RAF instructor and quickly progressed to solo and formation flying. The course included introduction to basic fighter tactics, formation flying, dogfighting, and simulated combat as well as night flying, instrument flying, and, in some variants, weapons training (carrying up to eight practice bombs and a single .303 machine gun).

Darling’s time at Watton lasted five weeks, enough time for him to disappear yet again. He had been on station only a week when he disappeared from station on September 6th and did not return until two and half days later on September 9th, reporting in at the main guard room and being arrested by a Corporal Bright of the RAF Service Police. At this point, it’s clear that Darling must have believed that the price he would pay in reprimand, detention or lost pay was worth the freedom to do whatever he was doing during these absences. As it turned out, he was merely reprimanded and docked three days pay. An RCAF sergeant’s pay in those days was around $2.00 per day. He paid double this low $6.00 fine for his speeding ticket in Ottawa in 1936. When one looks at the penalty, it does seem a fair price to buy yourself three nights on-the-town in King’s Lynn or Cambridge. We certainly can’t blame his truancy on a tryst with the lovely Marian as she was in Canada. For the time being.

RAF Watton in Norfolk was an important air base in the Second World War housing training, fighter and bomber units. The photo on the left was taken just a couple of months before Darling’s arrival at 7 (P) AFU, while the photo on the right was taken 12 months later when it was being used as a major overhaul depot for B-24 Liberators of the USAAF. What a difference a year made. Photos: RAF

Blackburn Botha Mk. I of No. 3 School of General Reconnaissance, RAF Squires Gate, out over the Irish Sea. Photo by Charles E. Brown, from the RAF Museum collection

Despite his growing list of transgressions of The Kings Regulations for the Royal Air Force, Darling successfully completed his advanced flying training including twin-engine time on the Avro Anson. On October 3rd, he was posted to No 3 School of General Reconnaissance at RAF Squires Gate (now Blackpool airport) on England’s northwest coast. The school had mainly Botha and Anson aircraft on strength and was concerned with maritime reconnaissance training and general overwater operations, facilitated by the close proximity of the Irish Sea. It becomes evident here that Darling was being groomed for something specific — long distance fighter reconnaissance operations over water. The school was famously equipped with the Blackburn Botha, which was considered generally unpopular with crews.

The Botha was widely regarded as one of the worst and most dangerous aircraft of the Second World War. Designed as a four-seat torpedo bomber and reconnaissance plane, it was severely underpowered, lacked stability, and featured a poor cockpit design which limited visibility. Despite 580 being built, it was withdrawn from front-line service in 1940 due to safety issues, ending up in training roles.

RAF Squires Gate, Blackpool with the Irish Sea in the background.

A newly-qualified pilot is introduced to the Supermarine Spitfire, a Mark IIB, P8315, by his instructor at No. 61 Operational Training Unit, Rednal, Shropshire. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Darling remained at Squires Gate through Christmas until January 19, 1943, when he was posted to No. 61 Operational Training Unit at RAF Rednal — a Spitfire training school. 61 OTU was an intensive training hub that converted newly-qualified pilots into combat-ready fighter pilots. They focused on formation flying, dogfighting tactics, and navigation in high-performance aircraft, often experiencing high accident rates due to intense, rapid, and demanding training scenarios. Training included air-to-air gunnery practice, formation flying, and navigation exercises. Instructors often were veterans of active squadrons, ensuring training reflected the latest aerial combat lessons.

The one problem with Rednal was it was in Shropshire, one of England’s least populated and remotest counties. Landlocked and far from the action, it was suitable for the training of fighter pilots away from the threats of Luftwaffe attack but for someone like Darling who liked to disappear to do God knows what, it was an unfortunate locale. The Rednal and West Felton Railway station was at the southern perimeter of the airfield, but where could he go AWOL for a night on the town? Oswestry? Shrewsbury? Wrockwardine? They weren’t too promising. It sure would be great if he could spend a night or two with his bride and he likely told her so in a letter or cable.

All of the young couple’s letters are lost to time so there is no way to know if they made a plan together to reunite. I suspect they had done this before however — in Montreal when Gordon was in training at No. 13 SFTS St. Hubert. He had disappeared for 17 days and then voluntarily returned. Success usually leads to repetition.

A Simple Plan

After arriving at RCAF Station Gander in late 1942, Marian began lobbying for permission to fly overseas to join her husband. Her request to take her leave in Great Britain by hopping a transatlantic ferry flight was denied. According to Gordon’s sister Audrey, “Marian had been trying to get overseas ever since my brother sailed, offering to buy her own passage but they would not sell it to her.” At the beginning of February however, she was granted three weeks leave from her duties in the Gander hospital. [The Sir Frederick Banting Memorial Hospital was named in honour of Dr. Frederick Banting, the co-discoverer of insulin, who died in a ferry aircraft crash in Newfoundland in February 1941 while on his way to England. — Ed.]. This gave her plenty of time to put into action a daring plan to stowaway aboard an eastbound transport aircraft when and if the chance ever came up. Because she was on her leave, she was not technically abandoning her duties, likely hoping to get back before her leave had expired. As the old adage goes, it’s better to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission.

It is not known whether Gordon Darling was in on the plan. Certainly he was not in on exactly when and how. She knew from talking to some of the civilian flight crews that an eastbound flight was quicker than a westbound flight, but still anywhere from 10 to 12 hours of tough going. She likely asked them a few questions which if answered would tell her if there was a place to hide inside any of these aircraft. She quite possibly convinced someone to give her a tour so she could “case the joint”. She may even have had an accomplice on the ramp. Perhaps she learned that it would be best to hop a ride on a non-stop flight to Scotland. If she got on an aircraft that was stopping in Narsarsuaq, Greenland and then Reykjavik, Iceland, she would be discovered early, or, depending on the weather, have to spend a night or more hiding in the parked aircraft. For sure, if she was discovered at either of those two airfields, she’d be detained and sent home on the next flight. Direct to Scotland would be her best hope.

On Sunday, February 6th, 1943, Marian took notice of a C-47 Dakota waiting for its crew to arrive from the Eastbound Hotel where they had rested for the night. They had brought the “Dak” from Dorval the day before and all day the maintenance staff worked to ready the aircraft for the long flight. While the aircraft had been in Dorval, it had been fitted with long-distance fuel tanks in the cabin and now all they needed to do was double check everything. Marian would have most certainly ascertained the crew’s destination before stealing on board. No point in getting into trouble on an aircraft headed somewhere other than Scotland.

The crew bus arrived early, dropping Tooker, Miller, McIntyre and Fraser off at flight operations to get the latest weather expected en route, plan the flight and listen to the maintenance chief’s report on the engines. They needed to be perfect, for they would be running for the better part of 12 hours. They were also particularly concerned that the rubber de-icing “boots” were functioning. These were rubber, inflatable protective strips installed on the leading edges of the aircraft’s wings and tail surfaces to remove ice accumulation in flight. If ice began to form, Tooker would activate the system, which pumps air into tubes inside the rubber, causing the boot to expand and fracture the ice. Without the boots, there was no chance they would even attempt the crossing, for a passage of the North Atlantic in February was a guarantee of icing. Tooker knew he had a narrow window to get the aircraft in the air ahead of the approaching poor weather and race it eastward. Ferry flights in 1943 were not for the cautious heart. They were for brave men who trusted their training and their equipment. And brave women too.

We cannot know exactly when Marian stole aboard the C-47 or how she did it without anyone noticing. It is possible that she slipped aboard while the aircraft was in the hangar. We know that the crew baggage and some winter clothing was already on board and piled at the back of the aircraft against the bulkhead behind which was the toilet. Perhaps the crew had stacked it there before the briefing. It seems that it might be easier to sneak aboard an aircraft from a doorway in the hangar than to run across an open ramp. The crew would then have to be aboard already, for it seems unlikely that they dragged their luggage out across the ramp in February and left their coats and jackets in the airplane before they went back to the hangar for a briefing.

If Marian was caught, she would have to contend with the likes of no-nonsense Gander Station Guards John Squires of St. John’s, Newfoundland [left] and John Freemen of Trinity Bay. Photo: Imperial War Museum

We’ll never know. But sometime before their departure, Marian, heart pounding, slipped unnoticed through the back door of Dakota FD773, wriggled her small frame behind some duffle and mail bags, pulled some discarded coats over her head and settled down for a very long and dangerous flight. If the Dakota was still in the hangar, she would have been listening as the crew boarded, heard the voices outside as the doors were opened and the felt the lurch as the aircraft was towed out on the ramp.

Gander sits pretty far north of Ottawa, about equivalent in latitude to Kapuskasing in Northern Ontario. The sun had sunk like a stone over the western horizon shortly after 6 PM, pulling a blanket of darkness over the rugged wilderness that squeezed in around Gander until all but the dimly-lit ramp and light from the windows of the hangar doors could be seen. Out beyond the pool of ramp light ran a low line of amber runway lights stretching into the gloom. The temperature was dropping and the sky began to lower as an approaching weather front dragged itself across Newfoundland from the west. Around 8 PM, it started to rain — the miserable rain of February in the northern Maritimes. The weather tomorrow promised near zero-visibility conditions in low, dense fog.

Around 8:30 PM, Marian heard the door shut across from her hiding place, then hollow sounds as someone clomped up the sloping floor towards the cockpit. Ten minutes later she heard the muffled whine and cough as the port engine started, felt it through the cold floor beneath her. A minute later the engine on her side roared to life and the scent of exhaust found its way into her dark hiding place. After a while she felt the Dakota begin to move. For long minutes, it trundled along beneath her. Brakes squealed, oleos thumped, jackscrews whirred, equipment rattled and squeaked — all sensed from inside her dark bolthole. There were no voices now. Just darkness and the cacophony of the ship as it worked its way to the threshold. After a while, the Dakota came to a stop and for a moment there was a pause, a sense of imminent decision and with it came terror for Marian. She lay hidden at the point of no return.

Around 9 PM, Tooker had centred the Dakota on the flarepath with his feet firmly planted on the toe brakes. He checked that the pressures and temperatures were where they needed to be, asked everyone if they were ready, looked at Burt with a nod and together they pushed the throttles forward until the engines were bellowing. His toes came off the brakes and Dakota FD773 commenced a slow-building surge down the runway; rain and sleet slanting through the landing light beams.

In the back under their coats, Marian felt the acceleration push her against the bulkhead, sensed the tail rise beneath her and began to feel reassured that she would see Gordon soon. She understood they were airborne when the tarmac noise fell away and the wheels came up with a hiss and a thunk. Here she would remain for the next ten hours—uncomfortable, hungry, cold and in a dream-like state as the seconds turned into minutes and hours.

Eleven hours later aboard Dakota FD773

Burt Miller lurched back to the toilet to relieve himself in the Elsan toilet. Not his favourite thing to do. The Elsan was a non-flushable chemical bucket system which functioned by collecting waste in a metal container filled with a formaldehyde-based chemical fluid to control odor and sanitize, though it often leaked or spilled during violent turbulence. One Second World War veteran had this to say about using the Elsan.

“While we were flying in rough air, this devil's convenience often shared its contents with the floor of the aircraft, the walls, and ceiling and sometimes, a bit remained in the container itself. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture what it was like trying to combat fear and airsickness while struggling to remove enough gear in cramped quarters and at the same time trying to use the bloody Elsan. If it wasn’t an invention of the devil, it certainly must have been one foisted on us by the enemy. When seated in frigid cold amid the cacophony of roaring engines and whistling air, away from what should have been one of life’s peaceful moments, the occupant had a chance to fully ponder the miserable condition of his life. This loathsome creation invariably overflowed on long trips and, in turbulence, was always prone to bathe the nether regions of the user. It was one of the true reminders to me that war is hell.”

In her hiding spot, Marian heard someone approaching again. Several times during the flight this had happened. She knew from the smell that the toilet was on the other side of the bulkhead. When Miller was finished he began rummaging for his flying jacket. As he pulled some clothing aside he was astonished to see a wide-eyed and beautiful young woman in an RCAF Women’s Division uniform and greatcoat staring up at him from behind the stowed luggage, blinking in the dim overhead lighting of the cabin. She smiled widely, apologized for frightening him and reached her delicate hand toward him. “Help me up please, I’m afraid I am a little stiff.”

After the initial shock for the crew, Marian explained her mission and apologized for stowing away. According to Tooker in a story on the front page of the Toronto Star a month later, she was given some cocoa and sandwiches and a seat in the cabin. “It sounds queer to hear a pilot on a transatlantic flight who has found a stowaway on his plane say that he put the whole thing out of his mind,” he said, “but that’s just what I did. We had ice on the wings and I was giving all my attention to setting that ship down in Scotland.”

While Marian kept herself warm in the cabin, the crew continued to battle the ice. It was then that they realized that if they had been much higher, the young lady in the back might have succumbed to hypoxia or the cold or both. While the Dakota had cabin heat, the heater often struggled to keep up In very low temperatures. One account I read noted that the heating was insufficient to stop a cup of coffee from freezing in the cabin during a January flight. It was fortunate that Tooker had crossed the Atlantic at an average of 12,000 ft, for they may have found Marian too late.

As they neared their destination, Tooker descended even further. Soon the Outer Hebridean Islands came into view on his left, the rocky archipelago reaching down from the north; then the island of Tiree. Minutes later, they were crossing the bleak peatlands of Islay with the whitewashed stone row houses of Port Charlotte standing out like snow on the bleak landscape, then Kilbrannan Sound, the Isle of Arran and finally the wide mouth of the Firth of Clyde. McIntyre was in touch with the Prestwick tower to inform them of their arrival and their surprise passenger. It was just after noon, Prestwick time when Tooker and Millar set FD773 down on a wet runway in sheeting rain and driving winds (54 kph and 8˚C).

Tooker taxied to the ramp where he was met by RAF Police, the duty officer and the curious. Men and women in the tower trained their binoculars on the passenger door as it was opened. One of the crew came out first and lowered a folding ladder then gallantly helped a young woman in uniform down onto the rain washed tarmac. The wind whipped her hair and skirt as she dropped her valise and shook hands with the officers. The other hand held her kepi tight to her head. Minutes later two more men jumped down from the doorway and stretched and a fourth still at the doorway began throwing baggage and mail down to the others. After a brief chat with the woman and the aircraft commander, the Duty Officer ushered the young woman into a waiting Humber staff car and they drove off through the security fence gate to the base commander’s office trailing exhaust. Tooker, Miller, McIntyre and Fraser remained standing in the driving mist, just happy to be breathing in some fresh sea air. After speaking with the attending ground crew, they gathered up their luggage and walked through the door of flight operations to get the Dak signed off. Then to the visiting aircrew barracks for a shower. They could taste that beer already.

Romantic Spunk

The exact order of events which followed is not recorded, but Marian was in trouble simply for making trouble for the Service Police. She had certainly done something that warranted some kind of punishment, but her large eyes, slim figure, blue uniform and love story worked their charms on authorities in Prestwick, Gander, Ottawa and London.

A report of her discovery over the Atlantic made it all the way to the Ottawa desk of the Right Honourable, Charles “Chubby” Power, Minister of National Defence for Air. It would be his decision as to whether Marian would be made an example of to discourage copycats and what her punishment should be. Certainly there were articles in the King’s Regulations and Orders that would cover such an event. The story was kept secret for a month before being released to the world’s press — perhaps waiting for the happy ending Marian wanted..

Chubby Powers decided that the story was just what Canadians and the world were looking for. When the story broke on March 8, The Toronto Star reported that:

“There were chuckles galore at R.C.A.F. headquarters today over the adventure of the attractive young stowaway bride, Airwoman Marion [sic] Darling who hid herself in a huge cargo plane at a Newfoundland base to be ferried to the United Kingdom to see her husband, Sergt. Pilot Gordon Darling.

“It’s the closest thing we’ve had to Wrong-Way Corrigan since the war started.” Hon. C.G. Power, air minister, said with a broad grin. “Sure, it’s against all rules; my girls will have to behave better than that as an example to the ‘Wrens’ and ‘WACs’.”

He declared the escapade is now all washed out and minor disciplinary steps have been taken. “She had been told never, never do it again.” the minister explained with a chuckle. Incidentally, the 25-year old bride gets her wish to be nearer her husband and has been attached to R.C.A.F headquarters in London. Mr. Power confessed he has a soft spot for the “romantic spunk” of a member of the R.C.A.F. Women’s Division; but did not want to encourage any others to duplicate the feat”

Marian’s story was picked up worldwide in early March, 1943, but Canadian newspapers gave it front page status. Image via Newspapers.com

The paper also interviewed Darling’s sister Audrey who had the latest news:

“We are all quite happy about the whole thing. Marion [sic] has been trying to get overseas since my brother sailed, offering to buy her passage, but they would not sell it to her. She is a swell girl. My brother and she met in Springfield two years ago shortly before he enlisted when he was on a visit there. When Marion [sic] was granted 21 days leave last month, I was to visit her in Springfield. Then she told me not to come. Next I got a cable from her saying that she and Gordon were spending a week together in Scotland.”

It’s clear from Audrey’s report that Marian and Gordon were reunited at some point before March 8, perhaps on leave following his training at 61 OTU at RAF Rednal. Bruce Pinch was at Rednal at the same time as Darling and an article published in the Owen Sound Sun-Times on March 18 showed that he was there when Darling and his wife were reunited:

“The two airmen trained together at the same centres in Canada, graduating as sergeant pilots at the same ceremony. Pinch was groomsman at the Darling wedding and was a witness at the happy reunion of the couple in Scotland.”

Marian was then provided with a new posting in the medical section of RCAF headquarters in London. In fact, instead of being punished, as the London Evening Standard reported later that summer: ““Never, never do it again” R.C.A.F. officials told her after her feat, but they promoted her from airwoman to the rank she held when discharged.” Marian would be assigned nursing duties with the Medical Branch of the RCAF at headquarters in London with the new rank of Assistant Section Officer.

In syndication

Newspapers across North America published some sort of variation of a newswire they had either received from Ottawa or Great Britain. Most pieces led with a photo showing the wide-eyed and delicate Marian to contrast with her bold adventure. Her face graced newspapers from Los Angeles to St. Johns, from London, England to Brainerd, Minnesota. Nearly every report had some detail wrong. Some seemed to just make up details out of thin air, but overall the story was understood — a diminutive, wide-eyed beauty, risked the Atlantic and the wrath of authorities to be with her fighting man! It seems very patronizing as seen through today’s lens, but back then, she had broken, or rather crossed, a barrier most women would never have even thought to approach.

Two of North America’s biggest syndicated women’s advice columns picked up Marian’s banner. We the Women, a column by Ruth Millett which ran as often as six days a week in more than 450 newspapers in the U.S. and Canada, included interviews with celebrities, commentaries on the effects of Second World War on American families, discussions of behaviour of elected officials and first ladies, and advice on topics such as whether women should work outside the home and how children should be educated. In late March, hundreds of small town and big city newspapers ran Millett’s “We the Women” piece on the inspiring adventures of Marian Darling:

“Envy of Lonely Wives”

“Wives whose husbands have been out of the country for long, lonely months got a thrill out of reading that a Massachusetts bride had hitched a ride across the ocean by stowaway in a ferry command plane.

Just as in a movie scenario the bride was reunited with her husband as he was getting ready to leave for another theatre of operations.

Many a wife, who has been living for V-mail** and an occasional cable, has speculated on how wonderful it would be if a wife could cross the ocean to see her warrior husband.

And now one wife has accomplished it. It is bound to make the ocean seem a little smaller to other wives. They’ll have to wait until the war’s end to be reunited with their men. But for a day or two they can think about the stowaway wife who actually got to see her man in the midst of the war. And they can think what it would be like if they could do the same.

And then they will have to go back to the job of patient waiting and working.

Even the wife who got across the ocean was separated from her husband after a short visit. And she was given a job too.

So now she is right back with the other war wives whose husbands are in foreign lands.

She managed to get a brief reunion—but for all her daring she had to go back to the ancient role of wives in wartime, the role of worrying, working—and waiting.”

** V-mail (Victory Mail) was a U.S. postal system during World War II that used microphotography to drastically cut the bulk and weight of mail sent to and from soldiers overseas, saving crucial cargo space for war supplies while still allowing personal communication through small, enlarged copies of letters. People wrote on special forms, which were then filmed, and the tiny film negatives were flown across oceans before being developed and printed at the destination for delivery, making mail faster and more efficient

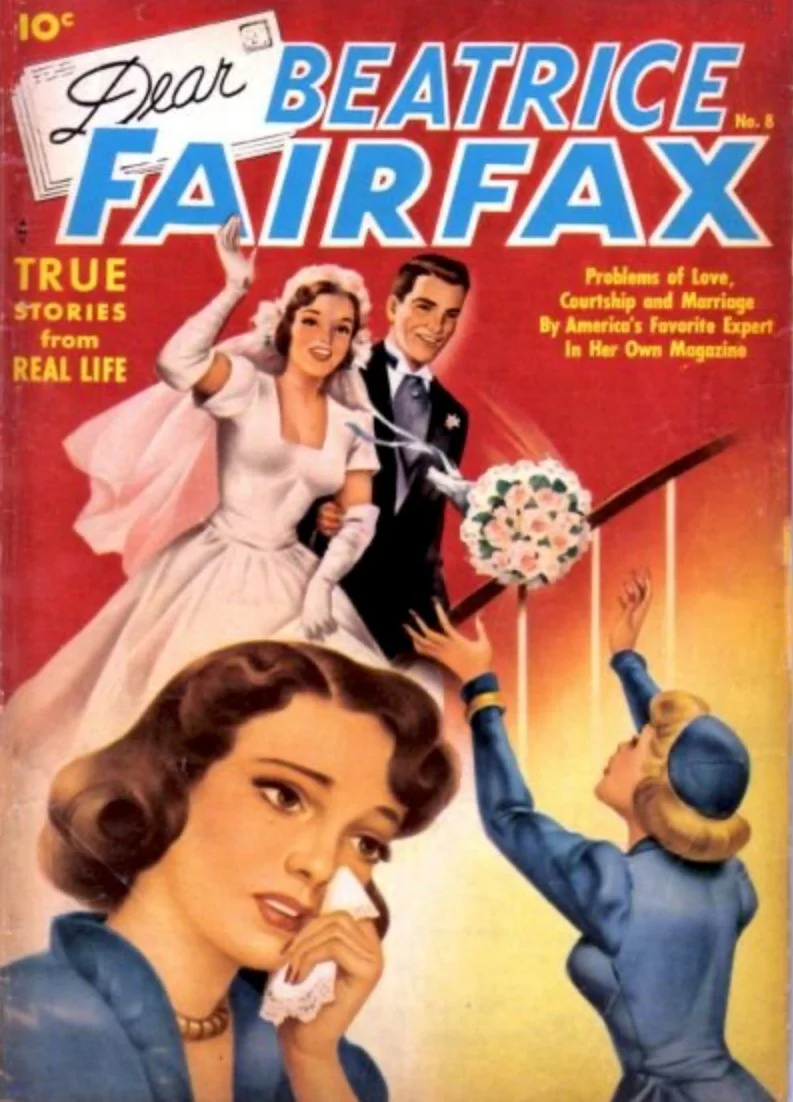

Another syndicated advice column entitled Ask (Dear) Beatrice Fairfax also covered the story:

“Divorce Caused by Greater Work Demand”

“Did you happen to see a newspaper picture of a girl with the caption “Sky Stowaway”? Her name was Marion [sic] Darling, and she was a member of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Canadian Flying Corps [sic].

This girl with the big appealing eyes and fragile daintiness, hid on a cargo transport and hopped the Atlantic from Newfoundland to see her husband in Britain. And for once, at least, the authorities, looking at the slip of a girl who may never have heard of the motto, “All for love and the world well lost,” failed to be hard-boiled.

Beatrice Fairfax was a cultural touchstone of the early 20th Century in America — made into a movie, a popular song and a series of saccharine comic books for teenage girls.

Ordinarily, the stowaway is given short shrift. He, and far less frequently, she is put on a carrier—ship or plane—and returned to the port of embarkation. Whether it was the girl’s beauty or the breathtaking quality of her romantic adventure, the authorities agreed Mrs. Darling might stay and visit her husband to whom she had not long been married. Somewhere in Great Britain, they enjoyed a belated honeymoon, before the husband left for another assignment far from both Canada and Britain.

Too bad that the happiest relationship that can exist between man and woman has a price tag on it. At a meeting I attended in a government auditorium in Washington a little while ago, I heard a nationally-known woman say that defense workers who weren’t stocking up on costume jewelry were buying divorces. And, she continued, “the day of marriage as a meal ticket is over. The Little Woman can now find herself a government job and dispense with a domesticated grouch.”

A few of us present, who didn’t think badly at all of marriage, husbands, homes, children, reminded her that the Government had semi-sponsored a clinic in that very building which, shorn of a few economic frills, might have been called “To catch your man, look your best.”

Beatrice Fairfax was the nom de plume for Marie Manning starting in the late 19th century, the precursor to modern advice to the lovelorn columns such as Dear Abby and Ann Landers. Despite becoming a national success story and having her column made into a hit song and even a major film, Manning was denied pay increases because she was “doing women’s work” and eventually resigned in protest. A series of other writers continued the column well into the 1960s. Sophisticates rated it as as a purveyor of “saccharine answers to sentimental missives”, but the Library of Virginia has a more progressive take on Ask Beatrice Fairfax in their UncommonWealth— Voices from the Library of Virginia blog:

[Ask Beatrice Fairfax] tackles familiar questions of infidelity, jealousy, protective parents, difficult in-laws, and the heartaches of romance. Yet these letters also reflect an America that was changing, with young people—particularly women—embracing new personal freedoms.”

A Type F.8 Mark II (20-inch lens) aerial camera being loaded into the vertical position in a Supermarine Spitfire PR Mark IV at Benson, Oxfordshire. By the time this photograph was taken, the F.8 had been largely supplanted in operational service in the United Kingdom by the Type F.52, and the aircraft pictured may have been operating in a training role. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Photo Recce Pilot

When Marian arrived in Prestwick, Gordon was still in Rednal learning to fly the Spitfire. Just two days after Marian’s arrival, he was finished and posted out to RAF Benson, home of Photo Recce for the Royal Air Force — a base serving as the premier hub for Allied Photographic Reconnaissance (PRU) from 1941. It was here in a one-month course that he would learn the trade of photo reconnaissance Spitfire pilot. Also based at Benson were a number of PR Spitfire and Mosquito Squadrons which would serve to teach newly minted pilots their trade — 540 (Mosquito), 541 (Spitfire), 542 (Spitfire), 543 (Spitfire) and 544 (Spitfire) Squadrons.

On arrival, he was posted to 542 Squadron, his first real operational unit. The squadron formed at RAF Benson on 19 October 1942 from two flights of 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (1PRU). For a period, it used nearby RAF Mount Farm as its operational base. The squadron had just re-equipped with Spitfire Mk IXs and was tasked to fly photo reconnaissance missions over Europe as well as train others in the art of PR.

Arriving at Benson that same week was his best man, Bruce Pinch, who had been through the same courses as Darling since arrival at Bournemouth. He too was assigned to 542 Squadron and they trained together for the PR role. At Benson, they accumulated another 14 hours or so on photo reconnaissance Spitfires flying low level for oblique shots and at altitudes over 30,000 feet for larger scale coverage.

Both Pinch and Darling were then selected to ferry Spitfires to 681 Squadron in India and perhaps to join them. To get there meant they would have to fly nearly 7,000 miles in a Spitfire. The trip would entail more Spitfire flying hours than either man had amassed so far with long flights over water and desert. It was a dangerous and daunting task given to young pilots with so little experience they would barely qualify for a flying instructor position in today’s world.

Sidebar: An Epic Journey to India

Sergeant Bruce Edward Pinch, after his wings ceremony at St. Hubert. A few weeks later, he was groomsman at Gordon Darling’s wedding. Photo via Newspapers.com

It’s truly hard to believe that these young pilots with so few flying hours under their belts would take on a journey of such epic proportions, flying from one exotic outpost to another in a powerful and sometimes temperamental fighter aircraft. Bruce Pinch was the first to go. On February 18, 1943, he signed for Spitfire AB319, a PR IV and took it on a 2.5 hour cross-country flight to test its fuel consumption, something he would really need to know in order to feel confident when flying long distance over water, especially on the England to Gibraltar leg of his journey. He returned to Benson and got ready to leave, handing over his personal effects to be flown to India by transport aircraft. At Benson, his Spitfire was fitted with long range fuel tanks or possibly under-the-belly slipper tanks. Six days later on the 24th, he left RAF Benson for RAF Portreath on the north coast of Cornwall, about as close to Gibraltar as he could get and still be in Great Britain. The next day, he took off and headed south over the English Channel and Bay of Biscay, found Cape Finisterre, and then, respecting their neutrality, skirted west of northern Spain and Portugal, made a left turn at Cape Vincent and landed at RAF North Front on Gibraltar 4.25 hours after taking off. That night he had a dinner of steak and eggs and noted it in his logbook. Next morning he took off from Gibraltar and headed due east for RAF Maison Blanche in Algiers, a flight of 2.75 hours. He must have gone into Algiers for the night as his logbook entry reads “Pretty Girls”.

The next day he fired up AB319 and headed southeast for 4.75 hours to RAF Marble Arch in Ras Lanuf, Libya. He was not as impressed with Ras Lanuf as he was with Algiers for his log book tells us he thought it was “A Hell of a Dump”. He was glad to get out of Libya the next day (Feb 28) for RAF Heliopolis in Cairo, four hours to the east. He made the most of his stay in Cairo, spending ten days there, enjoying the nightlife and the Pyramids. His log book sums it up well — “Good Beer”. On March 9th, he climbed back into a well-serviced AB319 and took off again for India and another long leg. His destination was RAF Shaibah near Basra, Iraq, but he got lost and after 4.75 hours flying time, force-landed in the desert at a railway station he called Ur Junction, Iraq. He waited there three days for fuel and carried on to Shaibah. Unfortunately, his Spitfire experienced a glycol leak and 1.5 hours later he force landed again, spending the night in the desert next to his Spitfire. He was picked up the next morning and driven to Shaibah. A repair crew got to work on AB319 and when complete, another pilot flew it off to Shaibah, where, five days later, Pinch took it aloft for 1. 75 hour performance test.

A later and substantially incorrect newspaper article in the Owen Sound Sun-Times based on a letter that Pinch had sent home to Thornbury waxed biblical about his adventures in Ur and Shaibah:

“Mrs. E. Pinch of the Thornbury public school teaching staff, received a letter on Saturday [April 3rd] written by her son, Pilot Officer [sic] Bruce Pinch, while en route from England to India in charge of a Wellington bomber [sic]. The letter was written from Iraq where the young airman made a forced landing almost on the spot [Ur—Ed.] where Abraham was born. During his short stay, he visited some of the really historic spots, including the abode of Belshazzar [the last co-regent ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire—Ed.], the prison and site of the fiery furnace where the three Hebrew children [Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego — ed,] were miraculously delivered as was Daniel from the lion’s den.”

On March 20, Pinch and his Spitfire took off for the Arabian Gulf coastal city-state of Sharjah of the Trucial States (Now the United Arab Emirates), a dusty, hot and very remote station inhabited by a squadron of Bristol Blenheims (244 Squadron) used on anti-submarine patrols in the Arabian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. He enjoyed the 3.5 hour flight over the red sands and turquoise waters of the Gulf with the narrows of the strategic Strait of Hormuz to his left. He spent the night in Mahatta Fort which had been built by the RAF before the war to protect the Imperial Airways Airstrip there.

RAF Sharjah in the Second World War, so typical of stations visited by Pinch on his journey to join 681 Squadron in RAF Dum Dum, Calcutta

Flight Sergeant Walter “Clarky” Clark. Image via findagrave.com

The next day, Pinch and AB319 took off for Jiwani, Persia (Iran), just a short 1.75 hour flight due east. He stopped long enough to have tea and cakes while his Spitfire was serviced and fuelled and took off again farther east to Karachi, India (now Pakistan), a flight of 1.5 hours. It seems there were issues with his Spitfire as well, for, in Karachi four days later, he made another performance test of .75 hours. Tragedy struck in Karachi on the same day, when another pilot who was making part of the journey with Pinch was killed. New Zealander Flight Sergeant Walter Norman Clark was executing his own performance test when, during a series of steep turns, his Spitfire (BR667) stalled and spun into the ground, bursting into flames. Pinch’s log book notes simply “Bad luck, Clarky killed.”

Clark’s death highlights the constant danger that these young and inexperienced fighter pilots were facing even without facing an enemy. Their experience on the Spitfire was minimal at best, yet they were asked to fly them 7,000 miles in variable weather conditions and temperatures. Clark was 22-years old and from Auckland, New Zealand. He is buried in the Karachi War Cemetery.

Pinch then waited two more days before launching for Jodhpur, India in Rajasthan, likely so that he and any companions could attend the burial of Flight Sergeant Clark. Pinch didn’t get far on the 27th, returning in 30 minutes due to an oil leak. The next morning (March 28) he completed the 2.25 hour flight to Jodhpur and that evening he visited the massive Umaid Bhawan Palace, built for Maharaja Umaid Singh and just completed that same year.

The route travelled by Sergeant Bruce Pinch was to be followed by Gordon Darling a month later. Map: Dave O’Malley

Spitfire PR IVt. Model by Pavel S at https://www.warbirds-blog.cz

The next morning he was off to Allahabad (now Prayagraj) along the Ganges River, where he remarked in his log book: “Hot as Hell”. It was no place for a Spitfire to run its engine for any extended period of time. The following day, March 30, 1943, he brought AB319 into RAF Dum Dum, Calcutta (now Kolkata) after a final 2.33 hour flight. His log book simply says… “They were glad to see us”. It is only at this point that I realized he was likely flying in the company of other Spitfires, at least on the last leg of the flight. The 681 Squadron ORB stated that two Spitfires, AB318 piloted by a Sergeant Huges (Possibly Hughes) and AB319 with Bruce Pinch, had arrived on that day. It was a stunning accomplishment— 39.25 hours of Spitfire flying and close to 7,000 miles. Just as he was on his last few legs, his pal Gordon was beginning his flight out of Benson, following the same route. After delivering his Spit, Pinch was sent to RAF Risalpur in what is now northern Pakistan for further training on Harvards and then Hurricanes. He was then posted to 155 Squadron flying Curtiss Mohawks.

They put Pinch’s Spitfire AB319 and Hughes’ AB318 to work immediately. The 681 Squadron ORB for April shows that a Flight Lieutenant Coombes in AB319 was flying a recce operation the very next day — to Magwe, Toungoo, Octwin, Nayaung-Bintha and Prome. Spitfire AB319 suffered engine trouble over Burma in June and made an emergency landing in Japanese-held territory. The pilot, Sgt P.S. Marman was injured when he overshot the runway at Alethangwin, but was able to evade capture and make his way to Allied territory. A month later, the Spitfire was destroyed by Vultee Vengeance dive bombers of 45 Sqdn, RAF, in order to prevent it being examined by the Japanese. In addition, AB318 was lost in June when Warrant Officer F.D.C. Brown lost control in severe turbulence and blacked out. He managed to bail out, but the aircraft was lost.

The Final Disappearance

Sometime in the middle of March, Gordon and Marian Darling spent their last evening together and made what was most certainly tearful goodbyes. Marian had taken such risks to be there with him and her emotional investment in their relationship had got her the honeymoon she had wanted. Now he was off to the other side of the world and she had to understand that there was no hope that she could join him there. He had received his orders to depart RAF Benson on the 18th of March in Spitfire PR IVt BS504, a brand-new Vokes-filtered photo-recce aircraft and fly to RAF Portreath, Cornwall.