THE SHEPHERD

It’s Christmas Eve and though just early evening, the dim light of winter is long receded, replaced by the orange vapour darkness of an urban night. Outside my house a Canadian hibernal front descends like a northern spirit to hush the city under a blanket of snow. Pressing my forehead against the windowpane, I feel the cold scrabbling at the glass and hear the faint swish of a trillion snowflakes crashing onto Adelaide Street. High above the walk, veils of snow sift across the streetlight’s reach. It’s a Christmas Eve most see only in greeting cards and the cinema. It’s a Canadian Silent Night. On nights like this I am envious of no one.

Behind me, in the living room, a fire snaps loudly and cheerfully flings a spatter of embers at the fireplace screen. Light flares over my shoulder and I turn towards it, with three fingers of Bushmill’s in my hand. Firelight throws an aurora borealis of shadow and light across the darkened room and onto the walls and ceiling. Along the mantle hangs the gleam of twenty-six silver Christmas ornaments dangling on red and green satin ribbons, each an annual gift from the family of a Mississippi fighter pilot friend. They represent to me what is wonderful about life and friends and aviation.

I watch my two beautiful daughters coming down the staircase now, dressed in their pyjamas and happy to be home. They skip past the glow of our little Christmas tree with the froth of wrapped gifts piling from its base and fight in jest over which couch they will occupy. They bring their pillows as they have always done and drag their duvets behind them like children. They are not children however. They are now beautiful, serene and grounded women living on their own. But tonight they are home with me and Susan and about to share a tradition that, for them, goes back as far as they can remember. It’s the night of The Shepherd.

Each Christmas Eve since it was first read nearly four decades ago, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation plays a recording of a forty-minute broadcast of Frederick Forsyth’s supernatural and haunting ghost story called The Shepherd. Forsyth, known worldwide for such fast-paced thrillers as The Day of the Jackal and Dogs of War, wrote The Shepherd in a day as a Christmas gift to his wife. As it turned out, it was a Christmas gift to the world, to Canada and to my daughters. One we have enjoyed together more than any.

“It’s a very lonely place, the sky, even more so the sky on a winter’s night. A single-seater jet fighter is a lonely home, a tiny steel box held aloft on stubby wings, hurled through freezing emptiness by a blazing tube throwing out the strength of six thousand horses every second that it burns.”

The story cannot be explained or reviewed in finer terms than the stunningly perfect words Forsyth chose to tell it in, and relating its beauty, simplicity and imagery cannot convey its power over my family and our lives. So I will not try. It is simply the short story of a Royal Air Force fighter pilot flying a de Havilland Vampire jet fighter back home from Germany in the winter of 1957. It is Christmas Eve in the story, as it is tonight, and the unknown pilot is trying to get home for Christmas when everything that could go wrong does. He finds himself over the North Sea at night, in winter, in the clag and without radio, navigational aid or time.

When all is lost and his fuel has thundered out the exhaust pipe and prayer is the only backup system still functioning, a ghostly silhouette of a de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber rises from the fog bank below him. And from this point, the finest-told ghost story of all time rises out of the mists along with the dark shape of the Mosquito.

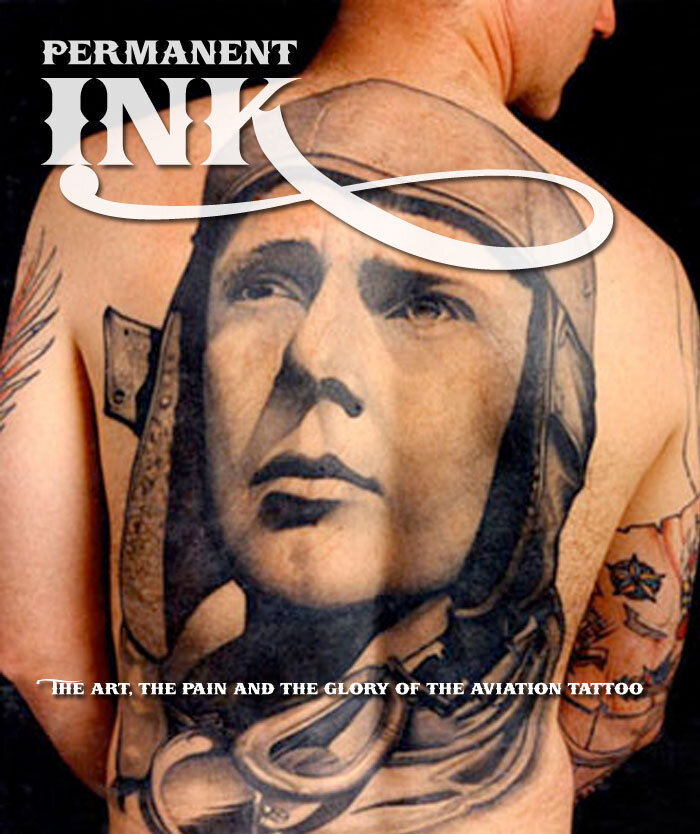

For the next forty minutes we are transported into the darkest of nights over the North Sea. We listen as a young man’s life unravels around him and his desperation rises. My daughters pull their duvets tighter under their chins and I draw down on the whiskey. The fire dies as the story is told. We do not move from our chairs or our personal thoughts and images. Each of us watches the same story with different eyes and emotions. That is the wonder of a radio play. I know what I see when the young pilot looks at the ghostly silhouette of the shepherd in the Mosquito’s cockpit. I see clearly his hand signals and in the dark I make them myself. I often wonder what my daughters see. Over a decade ago, my eldest daughter, an art student at the time, painted for me a sketch of what she saw when she heard The Shepherd. The gift was not just the little painting, but the knowledge that these Eves before Christmas Day spent by the fire light listening to a familiar tale meant as much to my daughters as they did to me. My younger daughter even wears a tattoo of a de Havilland Mosquito on her skin. That's proof to me that those moments we shared in the darkness at out home listening to The Shepherd are now part of our family DNA.

The small painting of the moment the Vampire pilot sees The Shepherd emerging along with hope from the North Sea cloud. My daughter gave me this nearly 8 years ago. Appropriately, it was a Christmas gift. Image by Lauren Grace O’Malley

“And then he came up towards me, swinging in towards my left-hand wing tip. I could make out the black hulk of him against the dim white sheet of fog below...”

Related Stories

Click on image

We’ve listened to it dozens of times now, but still it grips us, raising the hairs on the backs of our necks. We sit in the dark, lit by firelight and the glow of the FM tuner and float in the darkness on the waves of chilling words that swell through the night. By now we can almost recite the story word for word, but we don’t, preferring to shiver at the same places and smile in the darkness at the same place—“Not Jig King, but Johnny Kavanaugh!!” My youngest daughter always gives a snort of laughter along with me at this pivotal moment—not for any humour but for the staccato alliteration of its delivery. Such is Forsyth’s skill that we see the barely distinguishable shape emerging from the cloud bank below, we hear the icy howl of the Goblin engine, we feel the “Bam, Bam, Bammity-bam, rumble, rumble” of the fog-bound Minton runway.

The broadcast of The Shepherd is for my family, and many thousands like it across Canada, the quintessential Christmas story, second to none—not Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol nor O. Henry’s The Gift of the Magi. The story was first read on the air on Christmas Eve in 1979 by CBC broadcaster “Fireside” Al Maitland and his iconic recording from nearly four decades ago is still broadcast every Christmas Eve by CBC on As it Happens, the nightly radio show it originally aired on. This classic Canadian radio newsmagazine is still broadcast nightly from Monday to Friday, so if Christmas falls on a Sunday or Monday, The Shepherd is heard not on Christmas Eve but on the last show before Christmas—Friday night.

Frederick Forsyth was himself a National Service Royal Air Force Vampire pilot during the early 1950s—in fact the youngest in the RAF at the time. He was interviewed on As it Happens on one Christmas Eve just prior to the airing of Maitland’s much loved recording—as a gift of love from his fellow broadcasters to Fireside Al who was ill at the time. He died not long after.

If you want to imagine what this radio play feels like, think of It’s a Wonderful Life meets The Spirit of St. Louis meets Red Sovine’s classic Country Western ballad Big Joe and Phantom 309.

“Without warning, the shepherd pointed a single forefinger at me, then forward through the windscreen. It meant “There you are, fly on and land”, I stared forward through the now streaming windscreen. Nothing. Then, yes, something. A blur to the left, another to the right, then two, one each side. Ringed with haze, there were lights either side of me, in pairs, flashing past. I forced my eyes to see what lay between them. Nothing, blackness.”

“By the time the two headlights came groping out of the mist I felt frozen. The lights stopped twenty feet from the motionless Vampire, dwarfed by the fighter’s bulk. A voice called ‘Hallo there.’ ”

The Shepherd is, for me, one of but a few threads of family tradition left unbroken by happenstance, life changes and letting go. There is something about the music Maitland chose, the voices he animates the characters with and the whole world of imagination—a sky full of possibilities—that lays open before our closed eyes in that darkened room on that special night in my children’s childhood home.

As the story ends and a tale of courage is told, Susan, my daughters and I are left silent at the end. While the music drifts away into the dark, we all lie there with our thoughts and I know I feel as they do—that perhaps we are left a bit lonely and saddened knowing that a brave young man still flies the foggy night skies over the North Sea—never to come home, never to be warmed by fire or by love. In those final moments, I sense in the faint light of a fire long since reduced to embers, the true nature of the supreme sacrifice so many young men made so long ago. Young men who put the 20,000 beautiful days they were still due and the next 70 Christmases on the line for freedom and friends. It hurts to feel it in your gullet, but it is a beautiful thing regardless.

When all is said and done, there is one great role a father can play for his daughters. That is to protect them, to bring them solace and hope, to lead them and to support them - to show them the way. To be a Shepherd.

Happy Christmas, Lauren and Merrill

Love, Dad

If you can’t be by your radio on Christmas Eve to hear The Shepherd, here is a link to enjoy it anytime. A hint for full enjoyment: Turn the lights off, pour yourself a single malt.