THE MOMENT

The privileged spectators draw close. Conversations stop. All eyes are on the old contraption as it creeps up gently to the beautiful old biplane. Is it going to work? Is it going to turn the propeller? Will the rare 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine cough into life? Will that huge bicycle-chain mechanism come apart under load, spewing metal rods, gears and bushings all over the ramp?

We’re standing between the buildings of the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum. It’s an early Fall day, and a touch chilly. The rain is holding off, for now. A rare Hawker Hind is chocked into place on the ramp, gleaming silver fabric outlining its beautiful streamlined form. It’s the epitome of biplane grace. No between-war fighters ever looked finer than these Hawker machines, with their powerful R-R engines so elegantly cloaked and cowled. It’s the only one in Canada – for now.

The immaculate and elegant Hawker Hind of the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum is pulled from the facility's storage building. Photo: Peter Handley

In a cloud of smoke, Roger Hadfield fires up the “contraption” known as the Hucks Starter, while son Phil Hadfield looks on. Photo: Peter Handley

With fellow Hucks Starter builder Reg Miller guiding him, Roger Hadfield inches toward the priceless aviation artifact known as the Hawker Hind with the Hucks Starter. Photo: Peter Handley

Before the hook up and start, Dave Hadfield (right) shows Vintage Wings of Canada mechanics how the machine works. It will be these young superstars (L-R: Angela Gagnon, Andrej Janik and Xavier Simard) who will employ the Hucks to fire up our Hawker Fury in the years to come. Photo: Peter Handley

The ancient, modified Model T Truck approaches very slowly, inching in. The strange arrangement of overhead rods and shafts, born by an A-frame mounted on the wood body, closes with the delicate aeroplane. The Hind’s V-12 Kestrel engine is fronted by an enormous carved wooden propeller, and the approaching carbon-steel drive shaft could do irreparable damage.

The man in the left seat of the restored modified truck has his foot lightly on the left pedal, feathering it with the most gentle touch. All eyes focus as the distance shrinks to inches. A grey-haired man stands ahead and to one side. He holds up both hands, palms facing each other, measuring the distance between the end of the overhead shaft and the propeller’s hub, telegraphing the distance-to-go to the driver. His hands almost touch. The truck stops.

Two other men stand by the truck’s back wheels. They are holding large chocks, which are attached to the vehicle by spliced manila rope. At a signal they stoop and ram the chocks firmly in front of the rear wheels. Both machines are now chocked and can’t move. The shaft-end is 8 inches from the propeller, but can no longer strike it by accident. The spectators breathe a long sigh of relief.

Now there is a delay – the Model T driver is focused on something down on the floor, head bent, hand on a strange blue-painted lever. Several others crowd in to see. The driver joggles the lever as his foot caresses a pedal, and then the lever moves into place with a “click”. He looks up, smiles, holds up a thumb. The others back away.

With a strong leap, a blue-suited figure mounts the deck of the front of the Model T Truck, and grasps the overhead shaft. A hub extends from it, with two simple pin-handles. He grabs these and pushes firmly toward the propeller. As if by magic, an inner shaft emerges from the main shaft, and slides forward towards the prop. With a practiced twist, the pin-handles lock into a spiral groove in the propeller-hub. The man jumps down, grinning, holding a thumb up. The two machines, friends from long ago, are now linked for the first time in more than 70 years.

Phil Hadfield climbs aboard the front deck of the Hucks Starter, with Roger firmly on the brake. Photo: Peter Handley

As Roger inches forward, Phil lines up the drive shaft of the Hucks with the propeller hub. Photo: Peter Handley

It clearly takes a tall assistant to reach up and attach the shaft to the spiral-grooved receiver. Photo: Peter Handley

A man in a flight suit stands by the Hind’s wingtip, where driver and pilot can both see him. He calls to the pilot, not shouting, but projecting very clearly, “Fuel on? Mixture rich? Throttle set? Mags on? Contact?” and hears the pilot’s reply: “Contact!” The flight-suited arm is raised, thumb-up, and then whirled in a circular motion. This is the moment of truth. It happens now.

The Model T shakes as the RPM mounts, then the bicycle-chain-on-steroids starts to move. The shaft turns. As it does so all eyes are drawn to movement at the aeroplane. The propeller is turning! It make one revolution, then the engine gives a bark! It might work! But it doesn’t catch, and now comes the test for the weird mechanism mounted on the Model T – will it break apart under the load? The compression of the V-12 is fierce, plus it is a geared engine, with nearly a 2:1 ratio. The truck is trying to turn the little gear with the big one – like starting away in a car in high gear.

Three or four turns; the propeller spins. It functions! The Kestrel is turned strongly. Nothing gives way. There is a sudden Roar! The prop vanishes into a fast-spinning disc of motion. It starts! All eyes immediately focus on the shaft. Does it move back, out of the way? Will there be disaster – wood chips all over the asphalt? As if by an unseen force, the pin handles move away. The extended shaft retracts, clear of the prop. Success!

With back wheels solidly chocked to prevent forward motion, Roger engages the Hucks drive shaft and turns the propeller of the Hawker Hind. Photo: Peter Handley

As advertised, the Kestral barks to life and throws the Hucks device clear of the propeller hub. Photo: Peter Handley

With the Hind's Rolls Royce Kestral engine roaring to life, Roger backs away. Photo: Peter Handley

The Hind, which hasn't been started in a long time, is delighted to be outdoors and alive. Photo: Peter Handley

The Hawker Hind is indeed one of the most beautiful pre-war biplane fighters. Photo: Peter Handley

With great care the driver of the Model T moves the blue lever, then carefully backs away. The chocks drag-along on the ends of their ropes, which are measured to be short of the front wheels. The vehicle makes a 90-degree turn away from the path of the Hind and comes to a halt. Three men immediately approach the driver, huge grins splitting each face. Hands extend and are shaken.

Eyes link. The bellow of the revving-up Kestrel is too noisy for speech, but heads nod and hands grip. The moment passes, but there is a feeling of Victory.

It tastes sweet.

Before using the Hucks for another start of the Kestral, builder Reg Miller (L) and Phil Hadfield inspect the universal joint and chain drive for damage or loosening due to stress. Photo: Peter Handley

While Canadian Aviation and Space Museum staff enjoy the running of their Kestral in the background, and while, in the foreground, Reg and Roger discuss the event that just happened, Vintage Wings of Canada staffers Rob Fleck and Angela Gagnon inspect the worm drive and undersides of the Hucks Starter. Photo: Peter Handley

With the Hind still roaring merrily, Roger Hadfield chats with CASM Director General, Stephen Quick. Photo: Peter Handley

Vintage Wings of Canada engineer Paul Tremblay looks over the now-quiet Hawker Hind. Photo: Peter Handley

Vintage Wings mechanic Xavier Simard looks on seriously as Phil Hadfield makes some fine adjustments to the Hucks Starter. Photo: Peter Handley

Phil drives this time, bringing the Hucks in to line up on the now warm Hawker Hind and a second start. Photo: Peter Handley

Aligning the Hucks properly takes a team. Here Roger, the Hadfield patriarch, talks son Phil in close. Photo: Peter Handley

With Dad (right) looking on, Dave Hadfield shows Andrej Janik the proper technique for Hucks attachment. Photo: Peter Handley

Step One: Attach the Hucks Starter to the spiral cleat on the nose of the Hind. Photo: Peter Handley

Step Two: Engage the starter and rotate the propeller. Here we see exhaust coming from the rear left cylinder as the engine fires. Photo: Peter Handley

Step Three: The engine catches, the and the propeller shaft spins faster than the Hucks shaft, thus spitting the Hucks free. If you look close, Handley has captured the Hucks at the millisecond it is released from the propeller hub. Photo: Peter Handley

The bungee attached to the inner shaft of the Hucks pulls it back smartly as the engine roars to life. Photo: Peter Handley

Three men with vision watch as the Hind thunders on the now-sunny CASM ramp. Left to right: Rob Fleck, President of VWC, Mike Potter, founder of VWC and Roger Hadfield. Photo: Peter Handley

The team: Members of the Hadfield Family, the Hucks Starter build team, Vintage Wings of Canada and the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum pose Photo: Peter Handley

Proud of what they have accomplished, the folks who built the Hucks pose at the end of the session. Left to Right: Roger Hadfield, Eleanor Hadfield, Laura Miller and Reg Miller. For a look at the really cool miniature machines and engines built by the Millers, visit Miller Workshop. Photo: Peter Handley

The Building of the Hucks

Why would anyone go to the trouble of replicating something as arcane as a Hucks Starter? What would possess anyone to do it? The answer lies with Mike Potter, as so many things do at Vintage Wings of Canada. Mike’s eye was long ago caught by the beauty of the Hawker biplanes. Eventually he had the opportunity to sponsor the restoration of a Hawker Fury, the most perfect of the Hawker line. (The Fury is well under way – stay tuned for a future story on this site.)

The epitome of biplane grace: the inimitable Hawker Fury. Photo: RAF

But he had no way of starting it. The Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine never had an electrical starter. Instead, the Royal Air Force employed the Hucks. While it appears to be a strange contraption – a Rube Goldberg apparatus, in fact it served quite well. The ground crews certainly preferred it to using the hand-cranks, which was a slow and painful process under anything but the most ideal conditions.

Grunt Work -- an early start of the CASM Hind's R-R Kestrel engine. There is no inertia-wheel at work here; these gentlemen are turning the engine over in direct-drive, one cylinder at a time. The spark and the mixture have to be exactly correct for a start to happen. Photo: CASM Image LIbrary

So, in 2010, Mike called Roger Hadfield, of Milton, Ontario, my Father. He knew that Roger was a vintage car enthusiast, and owned several Model T Fords. Also, Roger is a very experienced pilot. He flew Boeing B-17s for Kenting,de Havilland Doves in the corporate world, owns a SV4B Stampe biplane (in which he won several Aerobatics championships in the Intermediate category) and retired as a Douglas DC-8 Captain at Air Canada. Would Roger build VWC a Hucks Starter? Intrigued and challenged, he said yes.

Roger Hadfield's aviation roots go way back. Here he is in 1961, climbing Kenting Aviation's B-17E (CF-ICB) up to 30,000+ ft over Venezuela, for photographic mapping survey flights. Photo: Hadfield family collection

Roger as airshow performer at Geneseo in the mid-90s in the family SV4B Stampe (CG-OMD‚ which he still flies. Photo: Eric Dumigan

Roger’s connection with the Model T Ford, upon which a Hucks is based, goes way back. He traded a flock of sheep for one when he was fifteen. Later, as the car collection grew (it currently totals about 40 cars and tractors, including Canada’s oldest car, an 1897 High-Wheeler), he and his wife Eleanor ended up with four Ts.

Roger learned about Model Ts as a teenager when he traded a flock of sheep for one. Later he rebuilt several. Here, granddaughter Kelly Hadfield (Dave's daughter) goes solo in a restored 1915 Model T. Photo: Chris Hadfield

His first thought was that it had better be a Model T Truck, not a car. The truck drive shaft terminates in a worm-drive at the differential, resulting in a much slower and smoother approach to a valuable aeroplane. Research supported this. Also the Truck suspension better supports the heavy Hucks upperworks. Thus he put his old-car contacts into play and, within a few weeks, bought a Model T Truck engine and chassis from a restorer near Peterborough, Ontario. Roger is completely tuned-in to the vintage automobile world, and soon parts were arriving from all over the continent. In no time, he had a running engine on a chassis with wheels, and was driving around the yard seated on an old Evinrude gas tank.

"It runs! It moves" The Hucks' first journey, around the farmyard in Milton.

At the same time Roger realized that he needed to see a Hucks close-up. Drawings were non-existent. He organized a trip to England, where there are three Hucks. None of these are original, but the one at the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden was built in 1952 when there was still a living memory of Hucks use, and is probably the closest. Roger was allowed access, and he and Eleanor returned with over 500 photos and fond memories of the delightful people they’d met.

Roger with Peter MacAllister, builder of the most recent Hucks restoration in England, at the RAF Museum, Hendon, UK

Roger is a restorer and a natural engine man, but no machinist. The heart of the Hucks apparatus is the dog-clutch, where power is transferred from the drive shaft to the Hucks drive-sprocket. Making that, and the upper works, stumped him. Fortunately he knew of Reg Miller of St. Thomas, again through his old car connections. Reg was the man everyone went to when they had a particularly difficult part to be replicated, a machinist “par excellence”. Would Reg be interested? Again, the answer was “Yes”.

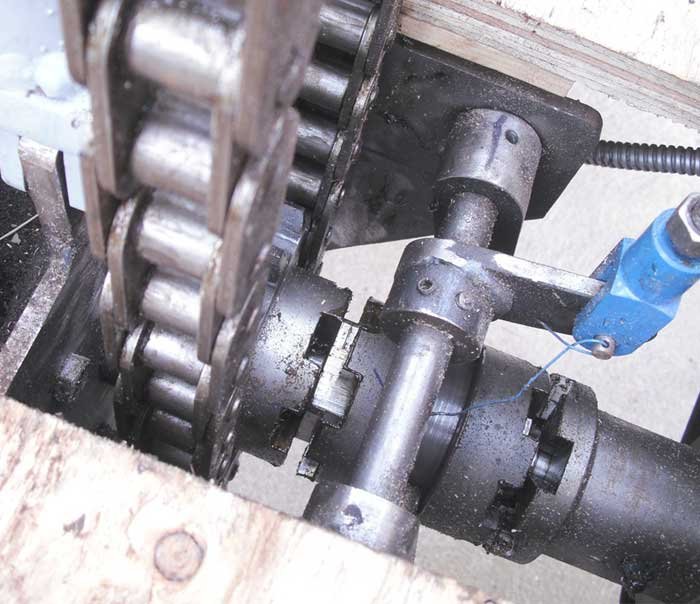

The heart of the Hucks: the dog-clutch. When it shifts to the left, it engages the drive-sprocket for the overhead chain. When shifted to the right, it powers the drive shaft and thus the rear wheels. The was re-created from photos and sketches, but no proper drawings, by machinist-volunteer Reg Miller, St. Thomas, Ontario, and worked flawlessly, first time! Photo: Dave Hadfield

Reg survived 18 years of crop-dusting in everything from Piper J-3 Cubs to 450 HP Boeing Stearmans before deciding to work as a machinist and engineer. He ran a manufacturing plant, and could invent and build anything. Later, in retirement, he built many enormously complicated miniature gas or stream powered engines in his basement shop. He won many prizes. He said he’d been looking for a project he “could sink his teeth into.” Roger delivered him the engine/chassis.

Reg Miller, machinist extraordinaire. His models have won prizes at many shows. They run and move as per the full-size versions. All parts are built by Reg – down to the spark plugs. Photo: Dave Hadfield

So during the winter of 2010/2011, a strange contraption grew amongst the rafters of Reg’s old single-car garage. Since the Hucks is tall, and the garage is low, the vehicle had to be jiggled back and forth as the pieces came together, literally weaving in between the roof trusses.

Re-creating a Hucks is a tall order – but Reg has a short garage. The upperworks had to be woven amongst the rafters during construction, then disassembled for transport. No problem. Photo: Dave Hadfield

In the spring it was disassembled, and Roger trailered it back to the farm. [insert photo: onto the trailer] This is where I came in -- an occasional boat-builder, always in wood. I gathered up my tools. The body of the Hucks is made of wood, strongly joined to support the weight of the upperworks. We had to make the truck’s box and seat, which hinges. And a deck had to be built out the front, also hinged so that the truck could be hand-started if necessary. The smell of freshly-sawn pine and spruce mingled with the engine-smells of the farm shop. In a couple of days we had it done – stout and strong.

Upperworks disassembled, friends and neighbours pressed into service, the Hucks is rolled onto Roger's trailer for the return journey to the farm.

Wood is good. In the Model T days, many of the custom-made bodies were built of wood just as is the framework for the Hucks. Here Dave, a builder of canoes and other small boats, has joined Roger in the shop for a session of sawdust and shavings. Photo: Dave Hadfield

The foredeck of the Hucks must hinge up to allow access to the hand-crank, for starting the Model T. And it must also support the weight of the crewman hooking-up the mechanism to the aircraft propeller. Photo: Dave Hadfield

"Hey, it's a truck!" Photo: Dave Hadfield

Roger is the kind of man who is up early and working in his shop by 07:30 every day. He loves an interesting machine. All the parts were there, the tools were there, and a lifetime’s experience put to use. His son/my brother Phillip (also an Air Canada pilot) was often there, on Standby/Reserve at work, and helped quite a bit. In a mere couple of weeks it was assembled and ready to test. Reg had also built a receiver to go onto the hub of the Stampe, so the test-aircraft was right there.

It’s no big surprise now, but at the time it seemed like a major question – would it work? Of course it did, and the 142 HP Gipsy Major engine of the old family biplane (which also has no starter other than the Armstrong variety) spun into life.

The first test of the Hucks was on the Gipsy Major 10 of the Stampe (which has had no electric starter since the '70s, when such effete extraneous items were removed to save weight for aerobatic performance, as is right and proper). Here, the normal prop hub fitting has been replaced with a Hucks receiver made by Reg Miller. Photo: Dave Hadfield

First Test: at the hangar on the farm -- testing to see what needed fixing or adjusting prior to paint. The Hucks ran, and the propeller turned freely. Good News! The Gipsy, however, needed its carb cleaned out before it would run. Photo: Dave Hadfield

After that it was paint, detailing, and arranging it to be shipped. Since the VWoC hangar was full, and the Fury not yet ready, Stephen Quick of the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum at Rockcliffe allowed us to park it there. And so we rolled it in front of the Hawker Hind, drained the gasoline and disconnected the battery, and waited for the day when we could start the Rolls-Royce Kestrel.

Phil Hadfield, whose other occupation is B-767 Captain for Air Canada, adjusts the starter shaft. This photo taken later, after the Hucks was painted, during a Rolls-Royce Club event. Photo: George Morita

Starting the Stampe. Looking at the angle, it can be seen that the Hucks is built for the much-taller Hawker Fury. (What no aircraft chocks? No worries, the other end of the airplane is made fast to a tie-down.) Photo: George Morita

"Champagne and hors-d'oeuvres will be served after the Hucks performance." Photo: George Morita

"Wow, it actually spins!" Mike Potter checks-out on the Hucks Starter, coached by Phil and Roger. Photo: Dave Hadfield

Phil Hadfield has a fine eye -- the RCAF crest, painted by him freehand. Photo: Peter Handley

The Past

How did such an odd-looking device as the Hucks evolve?

Bentfield Hucks was a prewar pilot who achieved fame by being the first in England to perform a loop. He did it in a Bleriot monoplane (which calls for a level of intestinal fortitude not matched by this writer.) He joined the RFC and went to France in 1914. There he became ill and was invalided back to England, where later he found work flight-testing aircraft for Geoffrey de Havilland: for “Airco”. Click here to see Bentfield Hucks' obituary and a brief history of his accomplishments.

A typical scene that could be any part of the far-flung sun-scorched reaches of the Empire. Hucks Starters were used from Australia to Aboukir,

Getting these early engines started was difficult. They had to be hand-swung. For a low-horsepower rotary engine (in which all the cylinders and propeller rotate around a stationary crankshaft), as in a Sopwith Pup, it wasn’t physically too hard. Their compression was low. But as the engines grew larger, and as the V-8s and V-12s came along, they became stiffer, and hand-starting them became more dangerous. Captain Hucks must have seen many injuries, so he developed the starter that bears his name, and patented it.

Hucks Starters spread throughout the Commonwealth during the 1920s and '30s as well as the United States. Ground crews much preferred using them to risking arms and legs, particularly as engines grew bigger and delivered higher horsepower.

Geoffrey de Havilland was Chief Designer for "The Aircraft Manufacturing Company Ltd", or AIRCO. After 1920, he designed and built aircraft under his own name. In this photo the Hucks Patent is clearly identified. AIRCO built all the early Hucks.

It looks odd, of course. All those rods and pipes and chains look improvised and shaky. But in fact the RAF found it very simple and convenient to use, and Airco was commissioned to make hundreds. He chose the Ford Model T to build upon because by then about half the world’s vehicles were Model T’s – Ford was spooling-up to make over 8,000 per day. Many RAF service vehicles were based on T trucks and cars. Personnel already knew how to drive them and service them. And in daily use the men who had to get the aeroplanes started would have been much in favour of using the Hucks rather than risking their arms and legs.

The RCAF used Hucks Starters. This typical mid-30's scene at Camp Borden features a Fairchild FC-2, and a Lynx-engined Avro 504N.The ground crewman appears to be stowing the chocks after starting the trainer. Another ground crewman appears to be holding the 504's tail by a rope as the pilot climbs in. There are chains on the rear wheels of the Huck. (Some of those hangars survive.) Photo: RCAF

Poor Capt. Hucks survived all the uncertainties and vicissitudes of those early aircraft – who knows how many narrow escapes? – only to succumb to the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918.

So, how does it work?

The transmission is modified to add a dog-clutch, to transmit power to either the rear wheels, or the overhead mechanism via a chain-drive.

Sticking out the front there is a long shaft. It is adjustable at the front end by easing a clamp and then moving the collar up or down or sideways on the sheer legs. This allows it to line-up with the propeller hub.

To help take the weight, there is a higher “counterbalance” shaft attached by a cord, and the other end of it is fastened to a tightly-stretched heavy bungee cord – like a teeter-totter. This makes it much easier for the man lining-up the main shaft.

The main shaft is hollow, and made of square tube. Inside it is another square tube which extends out the front. It is free to slide. The pin-handles which lock into the propeller-hub are on this inner shaft. The rear end of this shaft is pulled aft by a bungee, hidden inside.

The pin-handles fit into a spiral groove machined into the receiver on the propeller hub. When the engine starts, the propeller spins much faster than the pin-handled shaft, thus kicking it back out the spiral, and then the hidden bungee pulls the inner shaft away from the prop. [insert word document with labeled photo] This stops the shaft hitting the spinning propeller. (It works like an automobile starter bendix.)

The truck re-engages the rear wheels via the dog-clutch, and then backs carefully away, dragging its chocks with it.

The RCAF used Hucks starters. Wat Martin, Canada’s De Havilland guru, says there was one on every RCAF base between the wars. They were used on post-WWI aircraft such as the DH4 and the DH9, then later on the Armstrong-Whitworth Siskin fighter aircraft and its Armstrong-Siddeley Jaguar 385 HP engine.

Another Borden scene with Avro 504Ns. CFB Borden's runways have recently been replaced by grass, just like in the photo, and a complete Avro 504K, airworthy until recently, is in their museum in one of those original hangars. Hmmm....

A post-war First World War de Havilland DH-4, at High River Alberta gets an assist from a Hucks.

Avro 504N at Borden. Note: the Le Rhone rotary-engined 504Ks were usually hand-started by pulling the propeller. When they were re-engined by the Armstrong-Siddeley Lynx, a radial, the compression was much higher, and the Hucks was often used.

The business end of an Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar, 385 HP, equipping an RCAF Siskin fighter. Note the Hucks receiver.

The standard RCAF trainer was the Avro 504K, with a Le Rhone rotary engine, and this was usually hand-started, but later they were modified to use the Armstrong-Siddeley Lynx engine of 160 HP, as the 504N, and for this the Hucks starter was used.

Similarly, they were used all over the world, particularly in the Commonwealth, but also by NACA, predecessor to NASA.

A NACA (Now NASA) Hucks starts a Vought VE-7 pursuit aircraft.

No one knows what happened to them. Presumably they went out of use as the more modern radial engines arrived, with integral electric starters. They were probably consumed by the scrap-metal-drives that accompanied the shortages of WWII. There isn’t a single original one left.

But now there’s one in Canada, and it works!