ONE LAST FIGHT

It was early in the morning, the summer of 1990. Like most days in Ottawa in July, it dawned cool and vibrant, but the temperature rose as swiftly as the sun and moisture lived in the air like a sleeping animal. I don’t remember exactly how we all got there, to the tennis court, that is. Can’t remember if I picked them up in the red rental Cadillac deVille I had for the week of the air show, or whether we all went in some convoy. It was a time before GPS and the little tennis court could only have been found if I had led the way.

It was at tiny Brantwood Park, along the steady moving water of the Rideau River, not all that far upstream from where it takes a 50 foot tumble into the broader Ottawa River. Two ball diamonds, two tennis courts, one basketball court, one wading pool for the kids—that’s about all the room there was. Brantwood is hidden from all roads except for the one that leads to it. My dad used to take us there in the 1950s to swim, before it was deemed unsafe to play in the Rideau and we used to fish with bamboo rods on the eastern shore.

I can feel that day and sense its light like it was yesterday, but some of the details are lost in time. The city was not yet awake. Mourning doves still cried sorrowfully from the telephone lines and jays scolded us from someone’s back yard. A few cicadas were ratcheting in the hidden trunks of trees like electric transformers about to explode—a harbinger of the heat that would soon weigh upon us. The last moving air of the day barely rustled the big maples in the park. I still hear the rhythmic sound of tennis balls hitting pavement, the chirp of running shoes, the elastic pop of tennis rackets and the grunts and hard breathing of two warriors. Two physically fit men in the prime of their lives. Two men who had trained most of those lives to fight each other one day... to the death. One a Muscovite, the other a Mississippian—they were about as far from each other culturally as can be imagined and the fight was far different than that for which they had trained.

Valery Evgenyeva Menitsky was massively built, chiseled in face and body, with a large sensual mouth and thick, well cut hair. In the west he could have been a movie idol. In 1990 he was 46 years old, a Russian test pilot legend and a Hero of the Soviet Union. He was born in Moscow at the peak of the brutish Stalinist era. The Great Patriotic War had been inculcated in his heart, its heroes he longed to stand among. He commanded any space in which he stood. His charisma was gravitational. His personality was massive too, his voice low and authoritative. He was the poster boy for Soviet era aviation, but he had never flown a combat mission. The love and respect in which he was held by his Russian peers was nothing short of religious. In a nation of hundreds of thousands of atheist military aviators, he was a deity. Warplanes were his business, but tennis was his game.

Across from him on that tennis court that morning was 42-year-old James Michael McAdams, a man with an entirely different build, but athletically powerful—shorter, built wiry and light on his feet, he was what you might call a natural. McAdams had college good looks, with an Ivy League air about him. He had a refined and gentle voice, with a Dixie musical tone right out of a Tennessee Williams play. He looked you up and down before he spoke. He lived his life with a perpetual wry smile on his face and there was a sense that he had done many frightening things, yet they weighed not heavy on his heart. He came from cotton country in the Mississippi Delta where the heat of a summer’s day was an oven of discontent. He flew 242 combat missions in Vietnam, had eight Air Medals and three Distinguished Flying Crosses. He was shot down by a MiG-21 in 1972 and ejected over North Vietnamese waters of the Gulf of Tonkin. He was a Weekend Warrior with the Mississippi Air National Guard (MS ANG), the Magnolia Militia. Golf was his game now, but he’d played plenty of tennis at the Greenwood Golf and Country Club.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In the summer of 1990, the National Capital Air Show was making a transition from its small-town grassroots family beginnings at the Carp, Ontario airport, a former relief airfield for No. 2 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) to the Ottawa International Airport, site of No. 2 SFTS during the Second World War. It was an exciting, albeit uncertain, time. We had been growing steadily for five years and had outgrown the Carp airport where no fast mover or heavy military aircraft could land. If we wished to bring a bigger and better show to the people of Ottawa, we would have to move to a bigger place. We were led back then, for just this transition year, by former Golden Hawk pilot and Snowbird lead, George Miller, and his connections would help us achieve the headliner flying act that we needed to generate a success—a flying demonstration by a MiG-29 Fulcrum from the Mikoyan Design Bureau in Moscow—at little old Ottawa!

To come to our air show in Ottawa, the delegation from Mikoyan OKB, the MiG design bureau, had to travel from Moscow through Siberia and Alaska—an astonishing distance of more than 20,000 kilometres. They chose this route to avoid the diplomatic complexities of flying the shorter distance the other way round. Over Alaska, the two MiG-29s were escorted by American F-15 Eagles and then handed off to Canadian CF-18 Hornets at Elmendorf Air Force Base. They made a one day courtesy and refuelling stop in Comox, British Columbia and Winnipeg, Manitoba and then finally arrived overhead Ottawa a day before the show—in driving rain and heavy mists. Their one and only flypast was one for the ages—three CF-18s and two MiG-29s just below the ragged bottoms of rain laden clouds, no more than 200 feet above the airfield. The sight of the Russian jets, the red stars, the foreign camouflage patterns and the sound of all that weight being pushed 300 knots through the clag was astonishing. For all their sameness, these two powerful jets still carried an alien character, like spaceships arriving from a distant sun.

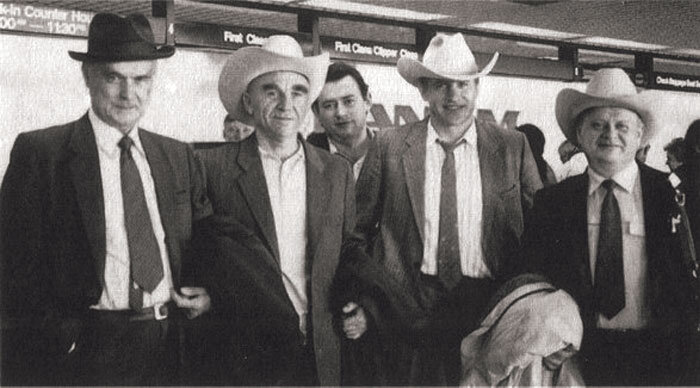

When the MiG-29’s travelling road show came across Canada in 1990, it paid a visit to Air Command headquarters in Winnipeg, Manitoba. There they were met by Lieutenant General Fred “Suds” Sutherland, who, 20 years later, would join the board of directors of Vintage Wings of Canada. L to R: Fred Sutherland, Yuri Bramkov, Roman Taskaev and Marat Alykov. Photo: Vic Johnson, DND

When the MiG-29’s travelling road show came across Canada in 1990, it paid a visit to Air Command headquarters in Winnipeg, Manitoba. There they were met by Lieutenant General Fred “Suds” Sutherland, who, 20 years later, would join the board of directors of Vintage Wings of Canada. L to R: Fred Sutherland, Yuri Bramkov, Roman Taskaev and Marat Alykov. Photo: Vic Johnson, DND

A Canadian CF-18 gets an up-close view of the MiG-29’s mighty Klimov turbofans en route to Ottawa for the National Capital Air Show. Photo: Vic Johnson, DND

Related Stories

Click on image

One of the most dramatic flypasts one will ever see. Through low scudding cloud and light rain, three CF-18 Hornets and two MiG-29s thunder west to east past the old terminal building at Ottawa’s Macdonald–Cartier International Airport. I remember this flypast well. I was standing, waiting for the arrival just to the right of the KC-135 Stratotanker seen in the upper right hand corner of this photo, where, in a few moments, the MiG-29s would shut down. The sight of two MiGs over Ottawa air space was awe-inspiring to anyone who had grown up in a Cold War culture with nuclear Armageddon seemingly right around the corner. Photo: Vic Johnson, DND

Here, the author (in trench coat) waits while the three MiG crew members discuss the flight from Winnipeg, Manitoba. The flight lead, Roman Taskaev (in dark green flight suit) chats with test pilot Marat Alykov (blue flight suit) and flight navigator Yuri Bramkov (partially obscured by Alykov). Photo: Author’s collection

Shortly after their arrival, they were followed by an Ilyushin Il-76 Candid, a large four-engined transport aircraft in civilian Aeroflot airline markings. In a rather amusing anecdote, the Il-76 was using full power on the two left engines to execute a difficult about face to its parking spot on Ottawa’s Bravo taxiway. The co-pilot was leaning out from his side window to his waist to make sure the right wing tip did not strike the perimeter fence and was looking to the right. As they pivoted, the jet wash from the two left engines came in contact with a mobile trailer housing our financial accounting office. Though it could have been worse, a rather terrified person exited the bouncing trailer, moments before it was flipped on its side. The Candid carried spares, tools and a full maintenance crew for both the MiGs and for itself. In addition, several high-ranking individuals and their entourages were on board, accommodated palletized airline seating. I had a peek inside the massive big heavy lifter and I can tell you... it was not luxury. The head of the delegation was a quiet, taciturn man by the name of Anatoly Belosvet, the Chief Designer at Mikoyan and the man responsible for the design of the MiG-29. Second to him was Valery Menitsky, the Chief test pilot for Mikoyan and a man everyone deferred to, save for Belosvet. When they stepped off the Candid, they were first and they were clearly in charge.

It was my job, along with two other friends, Peter Baird and Paul Larocque, to look after their wellbeing and to make sure that protocols were met. Peter and Paul had lots of experience dealing with Soviet and now Russian delegations and all three of us had recently returned from a junket to Leningrad. I had been taking private Russian lessons for a year, and we were, by default, the only ones to take on the task. Peter and I both had identical maroon red Cadillacs to squire Menitsky, Belosvet and the MiG pilots around in—and it was our job to pick them up in the mornings for the next week and bring them home or to parties after flying. For a thirty-something plane-struck graphic designer who was yet to get his pilot’s license, it was a dream assignment.

Just moments after the Russians stepped out of their MiGs, I introduced them to some good old boys from Mississippi. The boyish Marat Alykov in the trucker’s cap turns toward me with three members of the 153rd Tactical Recon Squadron “zapping” his two-seat MiG. On the left is Squadron commander, Colonel Bob Soulé, to the right of Alykov is Lieutenant Colonel Mike McAdams and Lieutenant Colonel Greg Williams—the Duke Brothers if there ever were. Photo: Dave O’Malley

On the Saturday, the boyish Alykov performed a 20 minute show in front of the crowd that left everyone speechless. It was a series of heart-stopping manoeuvres, the like of which we had never witnessed before—at least not in an air superiority fighter. Two manoeuvres stood out above all else. During the routine, Alykov performed two low-level tail slides—the aircraft pointed vertically with the throttle closed. The aircraft went silent, with gravity bringing it to a stop at no more than a thousand feet, hanging for an eternity before sliding back down its exhaust plume and snapping to a dive. Then there was the Cobra Manoeuvre.

We had heard about the Cobra for a few weeks and everyone speculated about whether the Russians were going to execute it. It was like wondering if a figure skater would or would not attempt a Quad Lutz or Salchow. No one knew for sure, and most people had no clue as to what it was... except to say, it had never been attempted in North America before.

I won’t get too far into the performance that the two demo pilots put on that weekend—Marat Alykov on the Saturday and Roman Taskaev on the Sunday—except to describe one moment in time that captures it all. When the Cobra happened, you could hear the collective breath of 100,000 people being sucked inwards. Alykov, flying from east to west, was slowing the thundering MiG-29 down to a couple of hundred knots, when the fighter bucked, nose pulling up past the vertical. The tail and engines seemed to sail past under the nose, so that for one awe inspiring moment, the jet appeared to be flipping on to its back. Then just as quickly, the nose snapped forward like a cobra striking. It was an astonishing manoeuvre that defied our basic understanding of aerodynamics—how could an airplane falling on its back instantly stop the backward movement and snap forward like that?

Knowing that the MiG-29 was coming to Ottawa, General Hall, the commander of a New York Air National Guard F-16 unit from Syracuse, had flown his entire pilot cadre up in the unit’s Weed Whacker (a Fairchild Metroliner). Hall and his pilots were given a flatbed semi-trailer to stand on for the demonstration. After Alykov had landed, the General jumped down from the platform, followed by a line of his pilots. As they began to edge through the crowd, the General passed by and turning to me, shaking his head in disbelief, uttered two words only: “Sierra Hotel!”... which, for those who are not familiar, stands for S-H and is code for Shit Hot! Then one by one, the F-16 pilots filed past and disappeared into the crowd. It’s not every day that a USAF general officer will acknowledge the enemy’s skills.

I was also with Menitsky and Belosvet on Sunday afternoon after Canada Day when the air show met with calamity. We were sitting in the VIP area, drinking cold beer and burning in the hot sun. My back was to the show line and the Russians were half engaged in the demonstration and half with the conversation at the table. At one point that terrible afternoon, Menitsky stood bolt upright, uttered a deep moan and said something terrible in Russian which clearly meant “No, God, No...” or something to that effect. I turned round to the direction and caught only a flame-filled rolling black mushroom cloud rising behind the tree line—Harry Tope in his beautiful P-51D Mustang named Death Rattler had just torque-stalled to his death in front of one hundred thousand people. And his wife was sitting with us at the table. I could not understand the words Menitsky uttered, but in them I understood a common bond that all aviators felt. They were words of heartfelt pain.

After the distress of that day, the group’s interpreter and an aerospace engineer himself, Sascha Velovich, asked me if I could organize a court for a tennis match as Menitsky and Belosvet wanted to get some exercise and burn off some steam. To be honest, I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but I knew that if we arrived early enough at a municipal park, we would have no trouble getting a court. I chose Brantwood Park, a little city playground on the Rideau River near my home. For opposition I chose my friend, Lieutenant Colonel Mike McAdams, one of four Mississippians who had flown from Meridian all the way to Ottawa. He was to play alternately with me and Alexander Manucharov, the Chief of the MiG-29 flight and technical crew. I assume that we arrived by Cadillac motorcade like heads of state, but I have no memory of that part. I also assume Velovich’s presence at the game, but have no memory of him actually being there, but he must have or we would not have been able to communicate with the Russians.

I remember that we were there very early, perhaps as early as 7:30 AM. The sun was up and the morning was fresh, but heading towards a steamy, uncomfortable afternoon. We needed to get the sweating done early. At first we played as pairs, Mike with Manucharov, and alternately myself, playing Valery and Anatoly. The game started well enough, but it soon became evident that Manucharov, Belosvet and especially myself, were not in the same league as Menitsky and the young Mississippian. My play was getting precariously close to an international embarrassment for the free world, when it was decided that the three of us would sit on the sidelines with Velovich and watch as the aggressive and formidable Menitsky went toe-to-toe with the tenacious and nimble McAdams. It was a physical power style against a more nuanced and technical game—a living metaphor for the Cold War and political approaches to military aviation. What followed was a match that lives on to this day in my memory for its warrior context and physical focus.

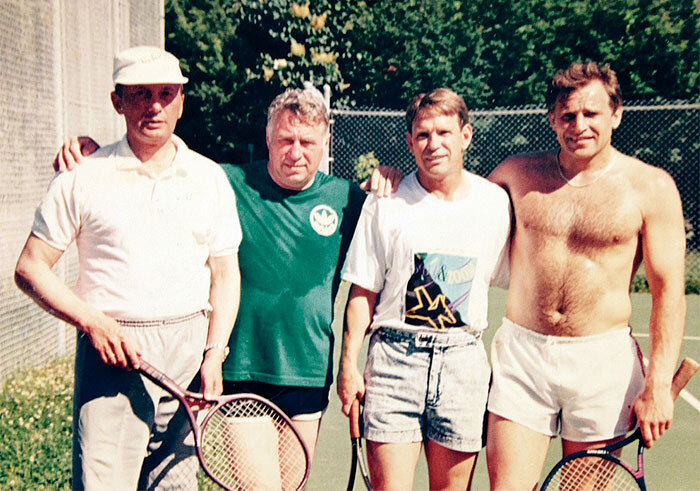

Left to right: Alexander Manucharov, Anatoly Belosvet, Mike McAdams and Valery Menitsky, at the end of the match. Photo: Mike McAdams Collection

Same group, except with the author. We were all so young then. It was, on reflection, an honour to have met Menitsky and Belosvet and to call Mike an old friend. Photo: Dave O’Malley Collection

Both men knew who their opponent was and who they represented and neither man would relent. For the better part of an hour, they grunted and gasped, trading shots, but neither saying a word. That little park, on the banks of the Rideau River, became a symbolic battleground for two trained sky warriors who, luckily, did not have to fight in combat. The temperature rose and the bigger Menitsky stripped down to his shorts, a definite dress code violation at the Greenwood, Mississippi Golf and Country Club. The neighbourhood rang with the fight, yet no one in the nearby yards and walkways would ever know that a battle royale was being waged, right here, right now, by the last Cold Warriors. Manucharov, Menitsky and Belosvet spoke little Russian, but Sascha Velovich interpreted in both directions. The four of us sat in the shade on park benches, bemused, delighted and secretly hoping for our sides to win. It was Menitsky who came out on top at the end, but there was no taunting celebration—neither man felt anything but joy and good fortune to have the chance to meet this way and share those things they had in common. The image of two Cold Warriors shaking hands, embracing and laughing at the end was a powerful one indeed—one that I would describe at cocktail parties for decades to come.

Of that amazing day, Mike McAdams reflected nearly 25 years later: “From the time I entered flight training I was always taught to fly and fight against Russian aircraft and Russian tactics. I always thought that the only time I would ever see a Russian airplane was over the skies of some foreign land. Nearing the end of the Cold War that day in the summer of 1990 I was able to meet and befriend several Russian airman at the air show. We bonded because of our mutual interest of flying, sports and drinking. We spent several days and nights enjoying these things. I learned that day that mutual interest can draw people together faster than differences can tear them apart.”

I even named a cat Menitsky, one I had bought for my daughters—a Red (of course) kitten that lasted about a year before disappearing, to my daughters’ great sadness. The following fall when I had a made-to-measure suit done, I had the opportunity to have my name embroidered inside. I chose to embroider Valery Menitsky’s instead. All my suits carried the names of aviator heroes of mine—Yuri Gagarin, Chuck Yeager, Orville Wright, Jesse O. Williams and Jeff Foss. This story would have remained a cocktail party ice breaker forever, except that recently I was down in Mississippi, enjoying an American Thanksgiving feast with McAdams and Greg Williams—now good friends for more almost 30 years. There, Mike and I started reminiscing about the good old days and the tennis match came up. Later that day, I began searching the web for entries about Valery Menitsky, Anatoly Belosvet and Sascha Velovich. What I found shocked me. The invincible and powerful Menitsky had died in 2008 and Belosvet had just passed away this past summer. I was truly saddened by these revelations. I had held these men in such high esteem, yet there was little to be found after even a lengthy search. Translating my search entries into Russian helped considerably, and I was able to find a good selection of low resolution photos from a website called My Sky Life—dedicated to Menitsky’s accomplishments and story. Looking at all the photos of the men he met, the things he did and the aircraft he flew, I knew that that game down by the river was one of my life’s richest moments.

There was so little on the English Internet about either man that I decided that, at the very least, I would tell the story of this inconsequential, yet powerful, moment in time so long ago, as a tribute to both Menitsky and Belosvet.

The Russian to English interpreter for the MiG visit was a young aerospace software engineer by the name of Alexander “Sascha” Velovich. Sascha and I got along very well, and we maintained a brief contact after that summer, but like so many other things, the beauty of that summer weekend drifted off over time and contact with Sascha was lost. I was able to find one photo of him on the Internet, oddly on a website called Wings Over Kansas. It was part of an interview made for an issue of Lockheed Martin’s Code One magazine. Sascha clearly went on to a very successful career at Mikoyan and in the Russian aerospace industry. Photo: WingsoverKansas.com

A short history of

James Michael McAdams, Greenwood, Mississippi

James Michael McAdams was born in the Delta cotton town of Greenwood, Mississippi—a community steeped in history and culture; a city that gave us both the blues legend Robert Johnson and the remorseless Klansman Byron De La Beckwith; and the talents of Morgan Freeman, Bobbie Gentry and Donna Tartt. It is a city of Rebels and American patriots, a place of immense human warmth and almost unbearable summer heat. McAdams was the son of an architect and following his service in Vietnam, he would attend the School of Architecture at Mississippi State University in Jackson. He practiced architecture in Greenwood and joined the Mississippi Air National Guard’s 153rd Tactical Recon Squadron, crewing the mighty RF-4 Phantom II on as many weekends as he could make.

The boys from the Magnolia Militia, the Mississippi Air National Guard’s 153rd Tactical Recon Squadron of the 186th Tactical Recon Group on their arrival at Ottawa International Airport for the West Carleton Air Show the year before the MiGs’ arrival. Left to right (ranks as per 1989): Colonel Bob Soulé of Meridian; Major Sam Clark of Tupelo, Major Mike McAdams of Greenwood and Major Greg Williams of Ocean Springs. There have never been a finer bunch of warriors and aviators as the men who flew their Phantoms from Dixie to Ottawa each year. This was the Magnolia Militia, the boys from Meridian, from Ocean Springs, from Greenwood and Tupelo, Vicksburg on the Big Muddy and Waynesboro on the Chickasawhay River. They weren’t some dumb-ass rednecks, barbequed and axle-greased, bib-overalled and scary. They were lovers of the world and all its sunny mornings, its fine restaurants and red, red wines, snowy slopes, and green fairways. They appreciated effort, showed respect for all people, laughed at good jokes and loved our great country as well as their own. Photo: Author’s collection

McAdams and Williams depart Ottawa in 1989. In 1990, after the visit of the Mikoyan Design Bureau to the National Capital Air Show, the 186th TRG made a major strategic decision that would affect its future for many decades to come—they got out of the jet fighter business and converted to flying the re-engined Boeing KC-135R Stratotanker—a decision that ended the careers of many a back seater. The move to the heavy and decidedly less sexy tanker was a decision that was not popular with true warriors like McAdams and Williams. Photo: Author’s collection

As a young Lieutenant in the United States Air Force, McAdams moved with his bride to Clark Air Force Base, where his squadron, the 523rd Tactical Fighter Squadron (The Crusaders), was based. The squadron had been assigned to PACAF (Pacific Air Forces) in 1965 at Clark and was providing crews on Temporary Duty (TDY) to the 13th Air Force in Thailand.

McAdams was a WSO, a Weapons Systems Officer, or Wizzo as the role was nicknamed (pilots liked to call them GIBs for Guy in Back). The WSO was responsible for navigation, weapons systems and radar operation, a critical component in a two-man team. Shortly after moving to Clark with his wife, McAdams was deployed on TDY to reinforce the 555th Squadron, the famous “Triple Nickel” squadron at Ubon, Thailand. The 555th had been led by the iconic Colonel Robin Olds just before McAdams got to Ubon. From there, McAdams flew combat missions over both North and South Vietnam. After 5 months with the Triple Nickel, the entire 523rd TFS was deployed in TDY to Udorn, Thailand. He joined his own squadron there and flew combat mission for another year. In all, McAdams flew 242 combat sorties, 142 of these over North Vietnam, and many of those during Operation Linebacker 1.

The young Phantom Wizzo would return safely in his aircraft from all but one of those 242 missions. On 30 July 1972, while flying a McDonnell Douglas F-4D Phantom (USAF serial 66-7597) on combat air patrol, covering a bombing mission to the suburbs of Hanoi, Captain James Michael McAdams and Captain George B. Brooks were engaged by North Vietnamese MiGs over the southern outskirts of the city. Most engagements with MiG defensive fighters over North Vietnam were shoot and run affairs, lasting a couple of minutes and even just a few seconds. From the call of “Tally Ho” to “Break it Off”, the dogfight that ensued lasted more than 8 minutes, an eternity in the dogfighting business. Four “Crusader” F-4 Phantoms took on four North Vietnamese MiG 21 “Fishbeds” and the wrestling, turning and depletion of energy soon had them jinking and duking it out down to 500 feet and even lower.

In all, the four Phantoms launched 8 AIM-7 radar guided missiles at the MiGs—four of them launched by McAdams. Due to the high G-loads in the turning fight, the missiles failed to lock on and instead went ballistic, departing control, with none exploding near the quarry.

However, one of the MiG-21s, flown by famed Vietnamese People’s Air Force ace Nguyễn Đức Soát managed to fire a missile which exploded right off McAdams’ wing tip during a high-G turn and blasting a six inch hole in the main fuel tank below and aft of his seat [Soát is presently the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Vietnam People’s Army]. With fuel streaming out and warnings going off, McAdams’ pilot, George Brooks, reefed the big fighter in a vertical climb to put as much air beneath them as possible. Immediately they knew they had to turn for their predetermined refuelling track to the west over Laos and headed there. It didn’t take them long to see that they were not going to make it and opted instead to make a 90º turn towards the Gulf of Tonkin, as fuel streamed from their belly.

McAdams and Brooks managed to get to the Gulf, but the engines flamed out over the beach. They knew they would cross “feet wet” 35 miles east of Thanh Hoa and had radioed for a tanker to meet them there. They had a visual on the KC-135 just as the last drops of gas were turned to noise and the Phantom went silent. They were able to milk it another three miles before they had to eject. Floating there on the Gulf of Tonkin, they watched North Vietnamese boats making their way towards them on one side and a helicopter coming from the other direction. Luckily, the Combat Search and Rescue chopper, from the United States Navy Helicopter Combat Support Squadron 7 (HC-7), known as the Sea Devils, made it to them first and hoisted both aboard their Sikorsky SH-3A Sea King, lovingly referred to as Big Mother.

Once aboard, McAdams was given a business card emblazoned with the HC-7 crest and the words “You fall, we haul—Dial 243.0 Any Time.” McAdams would return to combat flying, completing more than a full tour. He would be awarded eight Air Medals and three Distinguished Flying Crosses—one for his part in the May 1972 destruction of the Paul-Doumer Bridge over the Red River at Long Bien in Hanoi—one of the most heavily defended sites in North Vietnam.

“Hey, I bet this is me!”, jokes Mike McAdams at EAA’s AirVenture 1996 in Oshkosh as he points to a North Vietnamese “kill mark”. McAdams and Williams met me there for a few days of aero indulgence, when we spied this MiG-21 (“Bort Number” 4326) wearing the 13 victories of the mythical Colonel Tomb. During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese People’s Air Force painted victory stars on their aircraft for all claims made in that aircraft. The 13 stars here were likely the result of a number of pilots using that MiG to shoot down Americans. Photos of a MiG-21 sporting numerous red victory stars gave rise to the myth of Colonel Nguyen Toon or Colonel Tomb, who according to the legend, was shot down by Randall “Duke” Cunningham and William “Irish” Driscoll on 10 May 1972. While the two Navy F-4 crewmen may have in fact shot down 4326, the pilot was not Colonel Tomb, who never existed. North Vietnamese claim it was only a very successful propaganda fabrication. Photo: Dave O’Malley

A photograph of a Mississippi RF-4 Phantom II on approach to Aviano, Italy. While the unit never got the chance to show their mettle in combat during Desert Storm, they would occasionally deploy to Europe for extended periods. This Phantom still wears the camouflage from its days in Vietnam. Photo: Sergio Gava, Airliners.net

The Internet is a wonderful place... perhaps the greatest invention of all time. I was searching the Internet for information concerning the dogfight that resulted in Brooks and McAdams being shot down. I typed in the date and their names and the first thing that came up was a Wikipedia posting dedicated to Nguyễn Đức Soát, a North Vietnamese fighter pilot during the Vietnam War who became an ace—one of 21 pilots who can claim that title during the conflict—five Americans and 16 North Vietnamese. Of the five Americans only two, Steve Ritchie and Randall Cunningham were pilots, the other three being WSOs including Cunningham’s WSO Willie Driscoll and Ritchie’s WSO, Chuck DeBellevue. Soát’s victory over Brooks and McAdams was his fourth of the six he would end the war with. Soát was still active in the air force until recently, retiring as a Lieutenant General and Deputy Chief of Staff of the Vietnam People’s Army. Soát now heads up an organization called The Vietnam Bombs and Mines Action Support Association, recently established in Hanoi to assist efforts to deal with a country plagued by unexploded ordnance from more than half a century of modern wars. Photos via Vietnamese Internet sites

Nguyễn Đức Soát (fourth from left) and other North Vietnamese aces (including Nguyễn Văn Bảy (7 victories) and Nguyễn Văn Cốc (9 Victories)) pose for a publicity shot during the war, wearing their very distinctive Russian-made VKK-6M G-suits and high altitude pressurized helmets. When I contacted Lieutenant Colonel Mike McAdams after finding Soát’s claim to the victory, he replied with a smile “Holy Shit!... at least he was an ace and not a rookie.” Photo via Vietnamese Internet sites

A short history of

Valery Evgenyeva Menitsky

There is very little to find on the Internet about the life and times of Valery Menitsky. Perhaps a few photographs will help explain the accomplishments of this great man. He was born in Moscow on 8 February 1944 at the very height of the Great Patriotic War. He grew up with knowledge that someday he might have to take on the defence of the Motherland at all costs. Like so many of his age, there was no doubt he would serve his country.

He joined the Red Army in 1961 at the age of just 17. In 1965 he graduated from flight school at Tambov Military Flight School and in 1969 from Test Pilots’ School. From here he became a civilian test pilot with the Mikoyan OKB Design Bureau (In Russia at this time there was little distinction between civilian and military test pilots). He rose to great prominence here, taking time in 1975 to attend the Moscow Aviation Institute.

For his work on Project Spiral, the lifting body experiments that led up to the Buran, the Soviet version of the Space Shuttle, Menitsky was awarded the USSR’s highest honour—Hero of the Soviet Union. In 1983, he was awarded the title of Honoured Test Pilot of the Soviet Union. The following year he was made Chief Test Pilot for Mikoyan. His lists of awards at the end of his life were astonishing—The International Aviation Federation’s Gold Medal, the Lenin Premium and many more. In the capitalist era that emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Empire, he sat on the board of directors of a major Russian airline.

His work on all the great Mikoyan designs of the 1980s and 90s is the stuff of legends. His battle on the tennis court with McAdams was just a taste of his competitiveness and commitment to winning. In the end, there was one last fight—and sadly he did not win one last time. Valery Menitsky died after a long illness on Wednesday, 16 January 2008 in Moscow.

This group of hotshot Russian test pilots look like a bold bunch indeed. Valery Menitsky (second from left) stands with his fellow Mikoyan test pilots in front of the factory demonstrator MiG-31B, NATO-code named Foxhound. This MiG-31 prototype, designed by Anatoly Belosvet and test flown by Menitsky, was a developmental replacement of the earlier MiG-25 Foxbat supersonic interceptor. Photo: Mikoyan OKB (Mikoyan and Gurevich Design Bureau)

Two photos that span the full length of Valery Menitsky’s legendary flying career. Left: Young Lieutenant Valery Menitsky at the time of completion of flying training at the USSR’s Tambov Air Training Base, where he would have flown the Aero L-29 Delphin. Tambov is a small city 450 kilometres to the southeast of Moscow. On the right, he stands before a MiG aircraft, a living legend of Soviet and Russian aviation history. Photos via http://scilib.narod.ru/Avia/MySkyLife

According to the Google-translated caption that came with this photograph, it was taken on the “release” of Menitsky and his three friends from LII Test Pilot’s School in 1969. I’m assuming that this means “graduation”. Menitsky, always so identifiable with his handsome face, is at right. The other graduates are Mikhail Pokrovsky, instructor Yuri Sheviakov and Valery Stepanchonok. The date is 1969. Photos via http://scilib.narod.ru/Avia/MySkyLife

In October of 1983, Menistky was awarded, at the Kremlin, the title of Honoured Test Pilot of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The next day, after work, Menitsky and some of his esteemed friends celebrated over dinner and vodka. Left to right, the legendary Pyotr Ostapenko (now deceased), Roman Taskaev (travelled with Menitsky to Ottawa), the great Alexandr Fedotov (also deceased within a year of this photo), Valery Menitsky (deceased in 2008), the Kazakh astronaut Toktar Aubakirov, and test navigator Valery Zaitsev (who, within 6 months, would be killed in a crash while testing the MiG-31). Photos via http://scilib.narod.ru/Avia/MySkyLife

The photo on the left appears to have been taken in October of 1983, likely at the same time as the previous dinner photo, as he is wearing the same jacket and tie and decorations. The decoration he wears on his right lapel is the “Honoured Test Pilot of the USSR” and on his left lapel he wears the Hero of the Soviet Union, one of the highest decorations of the USSR. On the right, Menitsky in the 1990s as a Mikoyan OKB test pilot. Menitsky’s test career is stunning to say the least, having test flown fighters such as the MiG-21 (Fishbed), MiG- 23 (Flogger), (MiG-27 (Flogger-DJ), the MiG-25PD (Foxbat-E), the MiG-29M (Fulcrum-E ), and MiG-31(Foxhound). Photos: TestPilot.ru

Over many hours of searching on the web, it became apparent that there was not an abundance of photos of Anatoly Belosvet (right) and rarely any in the company of Valery Menitsky. I found this shot on My Sky Life, a website dedicated to the memory of Menitsky. It shows Belosvet and Menitsky back in Canada again in 1992, having just test flown a Jet Squalus, an Italian-designed light jet trainer, built by Promavia of Belgium. Only one was ever built, but Promavia had managed to partner with the Mikoyan Design Bureau—likely the reason behind the two MiG executives being associated with it, though they appear to be amused. Mikoyan, under Belosvet, lead the design of a next generation Squalus called the ATTA 3000, which, though capable, failed as the market favoured single engine turbo-props such as the Raytheon Harvard II. Later, the lone Squalus was sold to a Canadian creditor, Alberta Aerospace, where it languishes today. Photos via http://scilib.narod.ru/Avia/MySkyLife

There are even fewer photos of Alexander “Sascha” Velovich, a Mikoyan software and weapons systems designer when we met in 1990. He acted as the de facto interpreter for the MiG mission to Ottawa, and was surprisingly (to me) modern, liberal and outspoken in private. Here he hides behind Menitsky during another business trip to Texas in 1992. Photos via http://scilib.narod.ru/Avia/MySkyLife

This photo had no caption when I found it, but to those of us who follow such things, the three men in this image are unmistakable, just from the way they cut their hair—icons of Soviet aviation excellence and daring. Left to right: Valery Menitsky, Anatoly Kvochur and Roman Taskaev. They stand next to a MiG-29 Fulcrum at a Russian airfield.

Valery Menitsky was one of the test pilots on the MiG-105 concept aircraft. The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105 was part of a program known as the Spiral (aerospace system) was a manned test vehicle to explore low-speed handling and landing. It was a visible result of a Soviet project to create an orbital space aircraft similar to the space shuttle. This was originally conceived in response to the American X-20 Dyna-Soar military space project and may have been influenced by contemporary manned lifting body research being conducted by NASA. The MiG-105 was nicknamed “Lapot”, which is a Russian slang term for shoe, referring to the look of its nose. Only six Soviet test pilots were involved in Project Spiral, the test flying of the lifting body concept aircraft known as the MiG-105. Valery Menitsky was one of four Mikoyan pilots including Alexandr Fedotov, Aviard Fastovets and Pyotr Ostapenko. In addition, Ministry pilot Igor Volk and Air Force pilot Vasili Uryadov filled out the roster.

Though he never worked for Ilyushin, his name is honoured on the nose of a cargo variant of the enormous Il-96 four-engined widebody jet. The Polet Airlines II-96 Valery Menitsky lands at Novosibirsk-Tolmachevo in April 2011. Photo: Valery Fedorov

A close-up of the nose of the Polet Airlines Il-96, Valery Menitsky. Though one day this aircraft will be sold or scrapped and his name erased, the legend and the true story of Valery Menitsky will live on in the bold hearts of men who knew him. Photo: Alex Beltyukov, via Wikipedia

The death of Menitsky followed a lengthy illness. My ability with Russian is pretty poor, and even relying on Google translate, I was unable to determine the cause of his death, but it is likely cancer, a disease that does not discriminate—taking down the good and the great alike. The headstone on his grave in Moscow celebrates his greatest aviation achievement, the test flying of the legendary MiG-29 Fulcrum. In the upper left is a depiction of his greatest honour—the Hero of the Soviet Union. He is also a hero of anyone he met in life—bigger than life, physical, charismatic, a man’s man. I will always remember him with awe... and a bit of fear. Photo: warheroes.ru