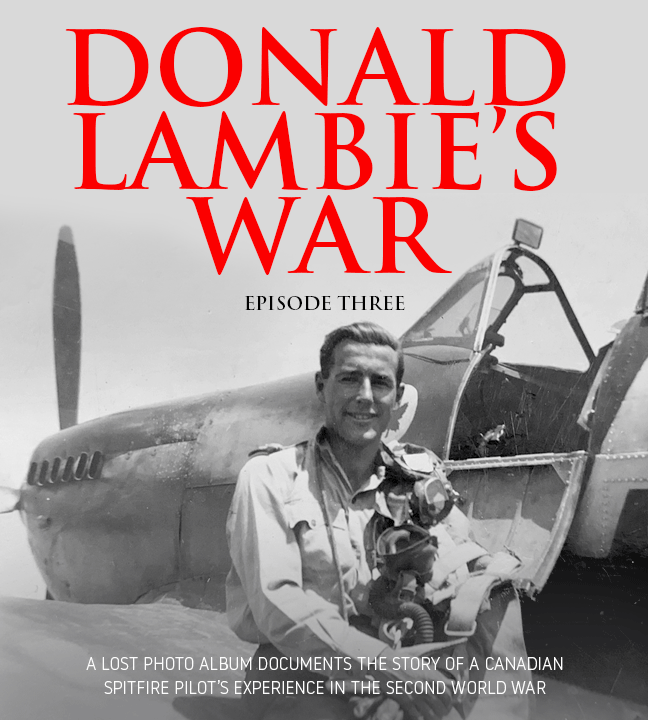

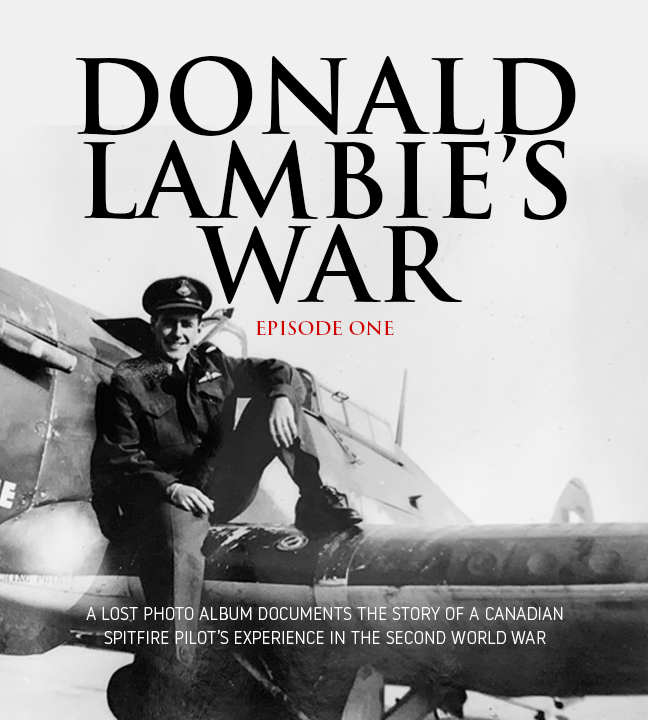

DONALD LAMBIE’S WAR - Episode Three

When last we saw our friend in Donald Lambie’s War — Episode Two, he was on his way to Bellaria from a Personnel Transit Centre in the south of Italy after having finished a short refresher Spitfire flying course at Guado, Italy.

Now after more than two years of heavy course work, tactical training and 346 hours of flying time under his belt (114.5 dual and 231.5 solo, 61 of which were in Spitfires), it was time to become a warrior instead of training to be one.

His new orders, received on 7 March, were to join 417 Squadron, RCAF at a captured Italian airfield located at Bellaria on the Adriatic Coast, nearly 700 kilometres farther north along the eastern Italian coast.

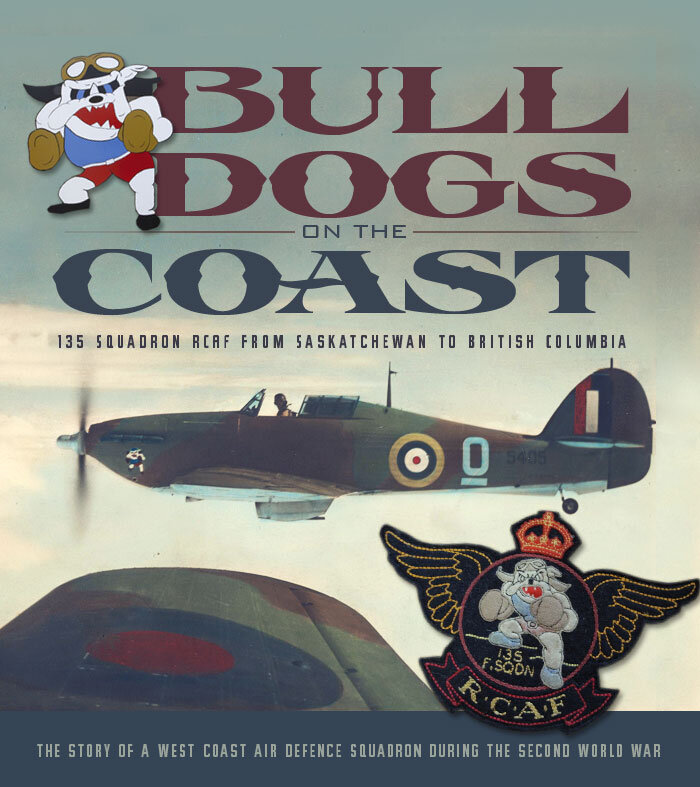

417 City of Windsor Squadron had been fighting in the war since the unit was stood up in late November of 1941 at RAF Charmy Down (a good name for a brand of soft bath tissue if there ever was one). It became fully operational on Supermarine Spitfires in February, 1942 and was employed conducting convoy patrol duties until March when the squadron and its aircraft moved to Scotland in preparation for overseas service.

417 pilots, ground support and staff moved to Egypt in June 1942, its aircrew being posted to the Aircraft Delivery Unit. In September it commenced operations again, remaining in the Suez area on defensive duties. The squadron moved on to offensive patrols in February, 1943 and following the clearance of Tunisia, staged out to Malta. During this period one of the Flight Commanders was the legendary James “Stocky” Edwards, the Hawk of Martuba and, until his very recent death, Canada’s and the Commonwealth’s highest scoring living ace at nearly 101 years old. The fortunes of 417 were down after this period and it gained a reputation for low morale and less-than-aggressive spirit. That all changed with the arrival of a new commander — Squadron Leader Stan “Bull” Turner, a 242 Canadian Squadron veteran of the Battle of Britain and a new flight commander “Flight Lieutenant Albert Houle, two men of legendary warrior status. Houle would complete another tour of duty as 417 Squadron Commander and cement 417’s well-earned new reputation as a respected and aggressive unit, called on by the Eighth Army to support them across Italy.

The unit was then deployed on cover patrols for the Sicily landings in July 1943, moving there a week later. It provided close-support for the Italy landings during August and September and moved across to Italy. The remainder of the year saw the unit in action during the Italian campaign and in early 1944 it covered the Anzio landings. It was committed to the Anzio battle until June when it moved north to fly patrols and bomber escort duties. It flew in support of the 8th Army and was engaged in this type of close air support when Lambie joined them. These were the kind of combat patrols that Lambie had particularly trained for in Canada and Egypt. There is no doubt that Lambie had heard about Edwards, Turner and Houle and the low-level close support that 417 was delivering and was proud and excited to be joining the squadron.

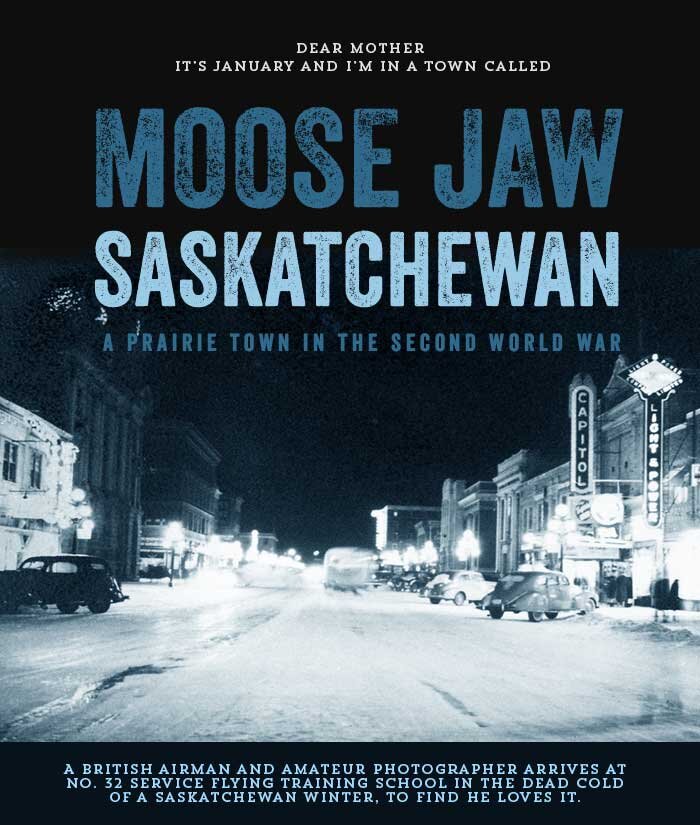

Though Lambie received his orders on 7 March but he didn’t join the squadron at Bellaria until the 15th which leads me to believe he made the long journey by truck or by train or more likely by both. There is no entry in his log that mentions a flight, something he did note on the way from Egypt to Naples. Either land mode of transportation would have required multiple stops, transport changes and places to eat and sleep along the way.

417 Squadron Operations, Bellaria, Italy

March 15 - May 2, 1945

Lambie joined the squadron on Thursday, March 15, 1945 — two years, five months and one week after he had enlisted. It was a long, long way to the war indeed and there is no doubt that the young man from NDG was glad to finally be “operational”. Joining him at the same time were his Ontario friends Jack Leach and Chuck Urie of Windsor, Ontario; Al White and Tony Whitlock of Toronto and Bob Latimer of Seeley’s Bay near Kingston. Lambie was assigned to “B” flight under the leadership of Flight Lieutenant Ralph Waldo “Nick” Nickerson. The squadron commander was Squadron Leader David Goldberg, DFC, a highly experienced fighter pilot from Hamilton, Ontario.

When Lambie joined 417 Squadron in March, 1945, it was led by Squadron Leader David Goldberg, DFC of Hamilton, Ontario. When war broke out in 1939, Goldberg had just completed a degree in business administration from Boston University. He returned to Canada immediately and attempted to join the Canadian Army but was refused. He joined the RCAF a year later and upon getting his wings he was posted to a training base in Canada. In late December, 1942 he travelled overseas for Spitfire fighter training and was posted to 416 Squadron, RCAF in the summer of 1943, followed shortly thereafter by a posting to 403 Squadron RCAF. On his 80th op, his Spitfire was damaged by flak and he force-landed in a farmer’s field. Knowing that being Jewish his fate would be harsh if the Germans captured him, he buried his dog tags and made a run for it. He managed to evade capture and with the aid of the French Resistance made his escape though Paris, Toulouse and then the Pyrenees to Spain. He returned to Great Britain and after a period of recovery was given command of 417 Squadron in November, 1944. After the war, Goldberg completed his law degree and while practicing in Hamilton, continued to fly Mustang and Vampire fighters with the RCAF Reserve until 1958. He died in 2006 at the age of 89. For more on Goldberg when he was with 416 Squadron click here. Photo vie Hamilton Jewish News

Having finally arrived, Lambie, an untested fighter pilot, was not going to be put on the line right away. He made his first two practice flights on 18 March, and then another the following day. After three hours flying time as a 417 pilot, he was given a short 30-minute hop testing a repaired Spitfire. When Goldberg and Nickerson found him ready for combat, his name was chalked on the Squadron Operations Board for the first time.

On March 20, in Spitfire AN-C, Lambie had his first combat sortie — a 1.5 hour-long armed recce carrying a 500 lb bomb on the centreline rack. He departed Bellaria at about 4 PM in the company of five other 417 Spitfires with Flight Lieutenant Karl Linton in command. The six conducted a wide-spread recce in hazy weather up the Piave River towards Belluno, a distance of over 200 kilometres with nothing of note until they turned for home and overflew Venice harbour which was still in German control. Here they spotted a 100 ft motorized vessel coming out and Linton took them in to attack with guns and bombs. All six bombs missed with one near miss and one that went astray and hit the breakwater. Lambie experienced intense light calibre flak in the dive but they all climbed out safely. On the way south to Bellaria, they strafed a truck, a heavy duty vehicle and a barge. They landed together at 7:30 PM.

In Lambie’s log book he notes much the same as the ORB: “1st Op. trip. Bomb wide. Int. L.F in Dive ”Saw 1 Puff!!!”. He had waited a long time for this and on his first “op” he’d experience flak, strafing and bombing. His next four ops were all in AN-C. On the first of these four, a long-range recce with a 45-gallon Long Range Tank strapped centreline, he notes enthusiastically “Saw Alps — From Above!”. The other three ops took him on similar missions — bombing barges in the Piave, transport lines in Conegliano-Vittorio and rail lines near Montebelluna, a few miles northwest of Treviso. While attacking the yards near Montebelluno he experience plenty of flak with “Puffs all around on pull-out” He had three more flights in March, but only one of them a combat op — cutting rail lines near Padua and Castlefanco on the 31st. By the end of March, Lambie was a fully-blooded ground-attack fighter pilot with 9.5 operational hours in his log book and 63 total Spitfire hours. There was no enemy air activity to speak of on any of these flights. The danger came at them from the ground.

April 1st, 1945, was both the 21st birthday of the Royal Canadian Air Force and Easter Sunday. Lambie flew two ops on this day — the first an afternoon bombing operation in Spitfire Mk VII AN-R under scattered clouds on a rail line between Vicenza and San Bonifacio, 30 kilometres east of Verona. The six-plane group Lambie was part of had four direct hits and two near-misses. An hour and half after they took off, they recovered safely at Bellaria. Despite the auspicious day, Lambie was kept on 5-minute readiness. He was scrambled in AN-H later that afternoon, but was recalled and was back on the ground in 20 minutes. It may have been the RCAF’s birthday and Easter, but it was also April Fool’s Day and Lambie notes this next to the 20-minute scramble in his logbook —“Recalled. Duff Call. April Fool’s Day”. I doubt he meant it was a practical joke, just a coincidence… but I am not sure.

417 Squadron Spitfires take off at five-minute intervals at Bellaria on the Adriatic coast (between Rimini and Ravenna) with the control tower in the cupola on the roof of the building at right. Lambie and his fellow pilots were doing exactly what they were taught at Camp Borden — providing ground support to Allied forces pushing the Germans farther up the Italian boot to Austria. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A photo taken from the airfield at Bellaria, Italy showing a 601 City of London Squadron lorry driving down the perimeter road. Lambie’s caption calls the lorry a “biscuit box” which must have been their nickname for that particular type. In the distance at left we see the squadron’s tents while the white building in the centre is identified as the airfield’s officer’s mess and quarters and the darker building (a former paediatric tuberculosis sanatorium) at right he identifies as the Education Office which also housed the “Windsor Club” for officers. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Pilot Officer Vern A. Herron and Flying Officer Douglas A. Love (rear) and Flight Lieutenant Tony Bryan, DFC and “A” Flight Commander Flight Lieutenant Karl Linton (front) lazing near tents outside the mess at Bellaria Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Related Stories

Click on image

Lambie’s photo of a muddy 417 Squadron flight line at Bellaria with Supermarine Spitfire Mk VIII, JF627 in the foreground. This particular Spitfire was flown by Don Lambie on only one occasion — on a long four-Spitfire recce to the area to the north of Venice from Conegliano to Udine. They came back with “No movement seen, nothing to report, No Flak”. According to airhistory.org.uk, an excellent online registry of the entire Spitfire production list, Spitfire JF627 wore the squadron code AN-M. This photo proves that incorrect. The Spitfire known as AN-M actually bore the serial number JF672 (last two numbers reversed). For the minutia-minded, here is a list of all 417 Squadron Spitfires flown by Lambie (the number of times he flew them is in brackets): LZ923 (35), JF423 (6), EN580 (4), MH770 (2), JG242 (2), MK148 (2), MJ366 (2), EN462 (2), MK284 (1), JG197 (1), JF627 (1), JG495 (1), JG337 (1), NH352 (1), and MH554 (1). The ink of Lambie’s personal address stamp on the back has worked its way to the front after 80 years. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Bob Latimer, Karl Linton and “one of the boys” with the Chevrolet flight truck on the line at Bellaria. Squadron Spitfires can be seen in the distance at right and Auster liaison aircraft at left. I love this scene so much — a Canadian boy in Italy reading letters from home while sitting on a Canadian truck with a Canadian maple leaf on the door and Canadian Spitfires in the distance. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The CMP (Canadian Military Pattern) truck (see previous photo) was made in the hundreds of thousands by Ford and Chevrolet in Oshawa, Ontario during the Second World War. It was configured in many different ways from fuel bowser to command car to cargo truck. Photo via Yorkshire Air Museum

A Day at the Beach

The Allied airfield at Bellaria in the province of Rimini was just a few hundred metres from the blue waters of the Adriatic Sea. Some time around the beginning of April, 1945, Lambie and a group of 417 pilots took an afternoon stroll over to the beach dressed for the cooler early Spring weather. Here, with the sun weakly shining and the blustering wind tousling their hair, they posed for Lambie’s camera. These photos, while not your typical wartime photos, show that the young men of 417 were truly brothers in arms. On the beach they took the time for a little relaxation after years of training and in the case of some pilots like Tony Bryan, years of fighting.

The photographs that Lambie took that day show young men who look as though they don’t quite know what to do with themselves — posing stiffly and somewhat self-consciously in a place that begs them to kick off their boots and take a walk in the surf and sand. Only Tony Bryan seems to relax, while Bob Latimer, as always, plays the clown. These are intimate moments that tell us more about these warriors than do your typical staged hero shots. The pairings of pilots are curious, perhaps best pals looking for a memento of their days together in Italy. Lambie was there with his camera to create those memories.

Flight Lieutenant Anthony John Adrian “Tony” Bryan, DFC, B-Flight leader, lounges on the beach at Bellaria in decidedly un-beach-like flying gear. Born in 1923 in Mexico of British parents, Tony was educated in England at St. Richard's prep school and then Ampleforth College. In 1942 he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force serving in 403 Squadron in the south of England. He flew over 250 missions and just weeks before D-Day, was shot down by anti-aircraft fire over German-occupied France. He hid from the Germans and eventually found members of the Resistance. After five months assisting the local French fighters, he returned to England, rejoined his squadron, and continued to fly sorties from Kenley, before being moved to Italy. After the war, Tony left the air force and attended Harvard College and then the Harvard Business School. His business successes are nothing short of spectacular — from Vice President of Monsanto, to Director of Federal Express, Chairman of the Chrysler Pension Fund, Koppers Corporation, AMRO Bank, PNC Financial Group, Imetal (Paris), First City National Bank of Houston, and Hospital Corporation of America International. He was a member of numerous golf and social clubs including, Gulfstream Country Club (Florida), Sunningdale Golf Club (London), The Union Club (NY), and the prestigious Augusta National Golf Club, home of The Masters tournament. He was runner up in the US National Doubles Squash Championships in 1957. He was a champion swimmer almost qualifying for the US Olympic team before the Second World War. He continued to fly after the war, flying a Super Decathlon as well as a SIAI Marchetti. He loved to demonstrate his flying skills for all his friends right up to eight weeks before his death. He died in Florida at the age of 86. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Warrant Officer Michael James Carroll and Flying Officer Alfred Alcide Desormeaux, (AKA “Des” or “Bug Eyes”) on the beach at Bellaria. Both Mike Carroll of Toronto and Lambie’s old friend Tony Whittingham left the squadron shortly after his arrival in Bellaria in mid-March which time stamps these beach shots at the end of March or beginning of April, 1945. Whittingham simply went over to 241 Squadron at Bellaria and Carroll, according to the ORB, was still on squadron but “awaiting disposal”. The 26-year old “Bug Eyes” Desormeaux was a dairy farmer from Winchester, Ontario, a small town south of Ottawa. He had joined the RCAF in 1941, training at the same EFTS and SFTS as did Lambie and had just got to the war ahead of him in February 1945. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Shiny vs dirty boots. Flying Officer George Herb Slack of rural Merivale, Ontario and Vern Herron of Toronto find themselves on a sunny Adriatic Sea beach — about as far away from home as they could have imagined just a few short years before. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Vern Herron, from the previous photo was from Toronto, Ontario. Upon returning to Canada at war’s end, he enrolled in the University of Toronto’s School of Dentistry in 1949. He caught pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital where he met his future wife whom he married in 1955. He moved his new dental practice to the town of Orillia, north of Toronto and raised his family there. Sadly, in 1973 at just 51 years old, he died in his sleep from a massive and unexpected heart attack. Photo: Dr. Vernon A. Herron Collection via daughter Marci Csumrik

Flying Officer George Herb Slack in Spitfire AN-Z at Bellaria in April of 1945. On the 25th of April, while taking off with Flying Officers Jack Leach and Tony Bryan, on a Rover mission (armed reconnaissance flights with attacks on opportunity targets), Slack’s Spitfire blew a tire and the 500 lb bomb he was carrying dropped off and rolled away without exploding. The Spitfire, RAF Serial No. MJ366, was a write-off. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

G. Herb Slack earned his pilot’s wings at No. 1 SFTS, Camp Borden on November 12, 1943, just a couple of weeks before Lambie got his at St. Hubert and was a close friend of Lambie’s on 417 Squadron. He was from a small community called Westboro near Ottawa which, today, is a central suburb of the city. Some records indicate his home as “Merivale”, an even smaller community just south of Westboro. I found only a single article referencing Herb Slack in the Ottawa broadsheet papers in the 1940s, and that was on April 17, 1947. We can see Herb at far left in this line-up of Merivale softball players being awarded the Bracken Trophy as Carleton County’s softball champions. Today, one of the important city streets in the Merivale area is called Slack Road. Photo via Newspapers.com

Nearly every photo of Bob Latimer in Lambie’s album shows a fun-loving guy. Perhaps his bigger-than-life personality went arm-in-arm with his diminutive size. Here, on the beach at Bellaria, he dons a German stahlhelm helmet and clowns around in the abandoned wreck of a German “Kübelwagen” (Jeep) that has been stripped of its tires, lamps and spare by locals. The looted German sign means something like “Pull Up”, probably from a Nazi checkpoint. Hanging off the empty windshield frame is a German infantry M42 field cap. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

It appears that the “Klimmesch” road/checkpoint sign was a popular prop for photos. Here we see Lambie’s friend from the Spitfire OTU, Flying Officer Jack Leach, standing next to abandoned German Army horse-drawn artillery limbers and caissons along a road near Bellaria. The curious boys made several sightseeing “field trips” to the front in search of souvenirs and information. The caption on the reverse of this photo states: “It wasn’t all modern by any means!! Those 88s” Perhaps these limbers were used to haul the feared and versatile German 88mm gun. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The month of April was a busy flying time for Lambie with 44 ops noted in his logbook. Most days he flew two ops and on the 7th, 13th, 16th, 19th and 21st he flew three ops each day. Each sortie involved some sort of recce, bombing and/or strafing of enemy ground targets. Eight of these flights were “Rover Paddy” ops and six were “Rover Davids”— The names Paddy and David were given to different types of Rover flights in the RAF. Here is an excellent description of the Italian campaign Rover concept from a Wikipedia post about Forward Air Control:

By the time the Italian Campaign had reached Rome, the Allies had established air superiority. They were then able to pre-schedule strikes by fighter-bomber squadrons; however, by the time the aircraft arrived in the strike area, oftimes the targets, which were usually trucks, had fled. The initial solution to fleeting targets was the British "Rover" system. These were pairings of air controllers and army liaison officers at the front; they were able to switch communications seamlessly from one brigade to another—hence Rover. Incoming strike aircraft arrived with pre-briefed targets, which they would strike 20 minutes after arriving on station only if the Rovers had not directed them to another more pressing target. Rovers might call on artillery to mark targets with smoke shells, or they might direct the fighters to map grid coordinates, or they might resort to a description of prominent terrain features as guidance. However, one drawback for the Rovers was the constant rotation of pilots, who were there for fortnightly stints, leading to a lack of institutional memory. US commanders, impressed by British at the Salerno landings, adapted their own doctrine to include many features of the British system.

Call signs for the Rovers were "Rover Paddy" and "Rover David" for the RAF; the names were those of the fighter pilots who originated the idea.

Several things from Lambie’s log book were of great interest to me during the month of April. On the 9th Lambie flew in a 12-plane formation tasked with bombing German infantry in dugouts as part of the Senio Offensive, the last big Allied ground offensive in the Italian campaign. The squadron ORB for 11 April states that:

“37 sorties today kept the squadron going “full bore”. The boys say the view of the operation from the air is terrific, but sight-seeing is dangerous because of the aircraft congestion.”

Lambie in Red section also carried out two strafing runs on enemy positions on 9 April and notes “A/C Galore in Area!!”. This was Lambie’s first flight in Spitfire Mk IX AN-T (Serial No. LZ923) which was to become “his kite”. From that day forward, Lambie was almost always in AN-T and ended up flying it on 35 ops and special flights. He would fly AN-T throughout the Senio Offensive and then as part of a squadron-sized VE-Day Balbo at war’s end. When 417’s war fighting days ended in May, Lambie flew AN-T to Udine in June and handed it back to the RAF. He never flew in a Spitfire again.

Things were not all sight-seeing and success. There were constant reminders of the dangers everyone in 417 Squadron still faced even though the war was clearly winding down. Flak was the big problem as was lack of focus. On 8 April, Flying Officer Roy Cotham of Pembroke, Ontario exploded in mid-air during a dive-bombing run against a rail line. The ORB states the event as inexplicable since neither of the two other pilots involved in the attack saw any flak. The ORB states “Roy’s loss is felt keenly as he was one of the most popular boys in the mess as well as being a “S.H.” Pilot [Shit Hot-ed]”.

Another friend of Lambie’s from training, Flying Officer Philip John “Mac” McNair of Edmonton, Alberta who was posted to 241 Squadron RAF (also attached to the group at Bellaria) was hit by flak on April 12. He suffered catastrophic damage to his elevators but managed to keep his aircraft airborne for a while. However at “about 9000' over Cervia aerodrome (only about 15 kilometres from home) flying straight and level towards Bellaria he was seen rolling over and spinning down into the sea.”

On 16 April, another 417 pilot, Flying Officer John Thomas “Jack” Rose of Chapleau, Ontario was shot down by flak on a Rover David operation whilst strafing slit trenches. His crash and death was witnessed by others in the squadron.

Flying Officer Frank Doyle of Vancouver British Columbia failed to return from operations on 22 April. No one knew what happened to him, so the assumption was that he had been killed or captured. In fact, he showed up three days later having evaded capture behind enemy lines with the help of Italian “peasants” (according to the ORB).

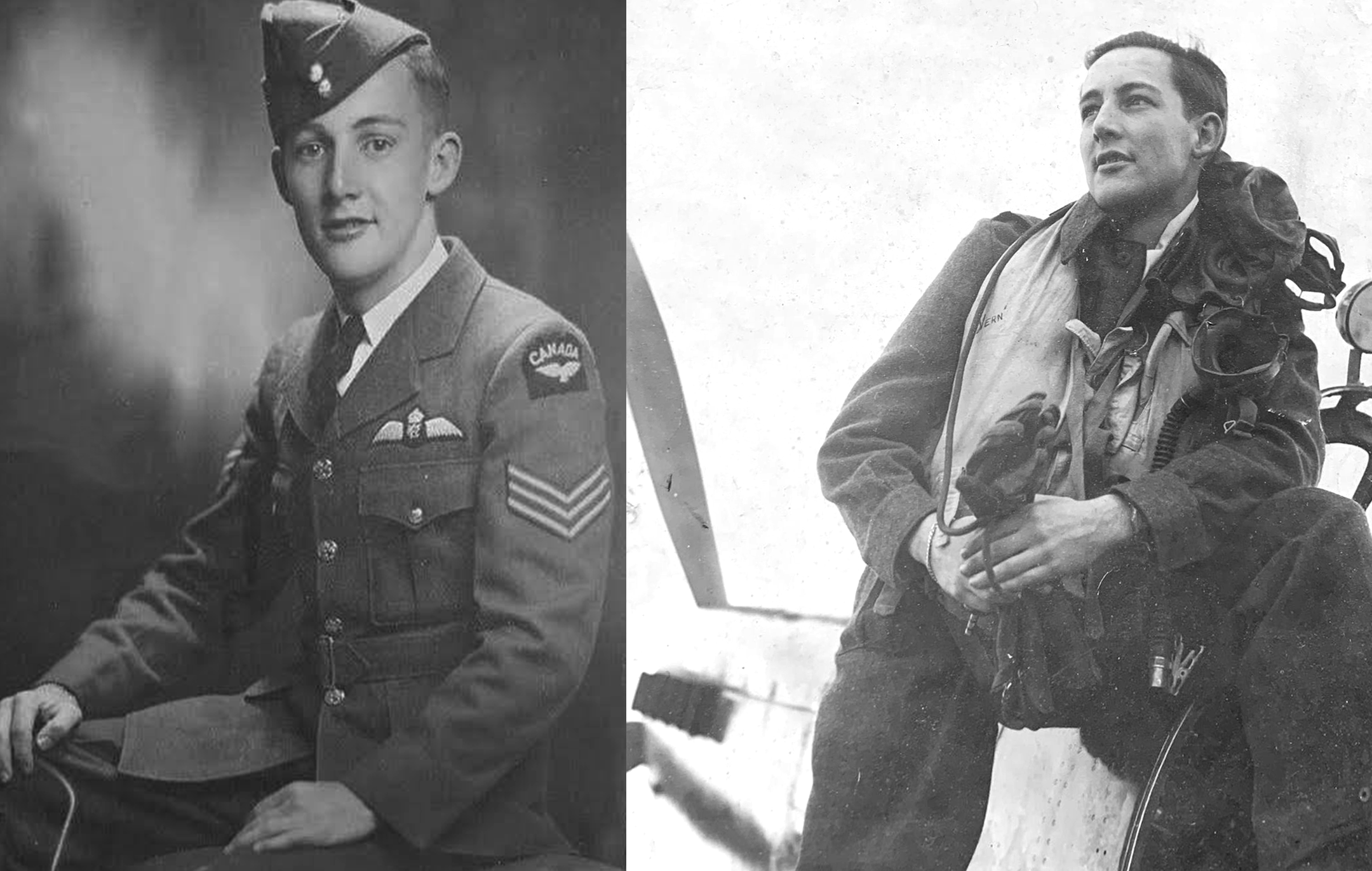

Lost comrades. Flying Officer Roy Cotnam (left) of Pembroke was killed on April 8 and Flying Officer Jack Rose (centre) of the logging and railroad town of Chapleau, Ontario on the 16th. Flying Officer “Mac” McNair of 241 Squadron, from Edmonton, Alberta, died on the 12th. Photos: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

The other interesting event in April was Lambie’s only wartime “prang” in a Spitfire. On the 26th, he took off at dawn on an hour and half-long armed recce with two 250 lb bombs underwing in the company of Karl Linton, G. P. Hope, Vern Herron, Chuck Holdway and Soupy Campbell. They bombed a road bridge — rather unsuccessfully — and returned to base. On landing, something happened — likely a ground loop, blown t1ire or gear collapse — but the ORB doesn’t even make mention of it. Lambie, however, sheepishly notes it in his logbook — “Bomb NM, 1st Prang and Last I hope!”. If he went into the last month of the war thinking it might be a piece of cake, the deaths of his friends and the close call in landing at Bellaria were sharp reminders that each day could be his last.

Lambie’s log book notes are peppered with acronyms like “NM”. Throughout the two pages dedicated to April, there are plenty of NMs (Near Misses) and VNMs (Very Near Misses) and only three D/Hs (Direct Hits). This is not a reflection of Lambie’s bombing skills, but rather of the difficulties and dangers associated with dive-bombing with an air superiority fighter at low level through flak. Generally, Lambie’s ops lasted between 1 and 1.5 hours, but on several occasions he strapped on long range tanks (45 or 90 gallon slipper tanks strapped beneath the fuselage between the wings) and pushed two hours. On 4 April, he had his longest op — two hours and ten minutes flying top cover escort for 16 South African Air Force B-26C Marauders of 30 Squadron sent to bomb the marshalling yards at Gorizia, near the Yugoslavian border.

Pilots and ground crew of 417 Squadron get in on a “big crap game” going on while they wait for “Wing-Ops” to find out where the front line was “so that the kites can get airborne”. It’s personal and candid photos like this that set the Lambie collection apart from the photos of other Allied airmen. It helps us see how they dealt with the tedium of operations. We can see by their dress that it is still cool in March in this part of the Italian Adriatic coast. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Adjacent to the Bellaria airfield, the wing requisitioned the Colonia Pavese, an Italian youth tuberculosis sanatorium as the headquarters and officer’s mess — known as the “Windsor Club”. Here they socialized and watched feature films such as on 3 April when they watched the comedy Roughly Speaking, starring Rosalind Russell, Jack Carson and Alan Hale Sr. The film was directed by Michael Curtiz the director of the film Captains of the Sky, a dramatic film about pilots training in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (Also starring Alan Hale Sr.). The ORB makes mention of the Windsor Club frequently, such as this note on the evening Roughly Speaking was screened: “The bar is resplendent in its array of new bottles of wine, cognac etc. as the result of a recent effort on the part of the bar officer, Flying Officer L. A. Thomas.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A postcard from the 1930s of the Colonia Pavese at Igea Marina Bellaria, locally known as “Pavia”. From what I can tell, it was some sort of tuberculosis sanatorium for children at risk of contracting the disease. Both before the war and after the war, the Adriatic beaches between Rimini in the south and Revenna in the north were very popular tourist destinations for middle-class Italians. It was an idyllic setting for children and youth to spend their mandated time away from their families for up to a year. The building was demolished in 1984.

Not the most pleasant looking building but home to 417 Squadron Officer’s quarters at Bellaria, Italy during Lambie’s time there. The back of the Colonia Pavese can be seen at the right. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Tony Whittingham, who had been with Lambie since their days together at No. 1 OTU at Bagotville in Quebec, pays a visit to his pal at the 417 Squadron officer’s quarters at Bellaria. Whittingham was posted to 417 a few weeks before Lambie arrived, but transferred over to 241 Squadron, RAF, a similar fighter unit sharing the field with 417 as part of 244 Wing, 211 Group of the Desert Air Force. He would go on to a stellar career in the Canadian civil service, retiring as Assistant Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Wherever he went, Lambie made friends and charmed the ladies… even the Italian locals in Bellaria. Here his good squadron buddy Jack Leach stands in the back doorway of the officers’ quarters with three women, listed as (L-R) Maria, “Butch” [Lambie’s quotation marks] and a relative of Maria’s. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Motley Crew. “Tiny” Lalonde (likely ground crew), Flying Officer “Bug Eyes” Desormeaux (squatting)‚ unidentified ground crew member, Flying Officer Larry Thomas, the mess officer and another member of the ground crew stretch their legs beside a 417 Squadron CMP truck “on a sightseeing trip to the front.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie ended April with two longer sorties. On the 29th, Lambie, led by Squadron Leader David Goldberg and in the company of All White, Vern Herron, Johnnie Johnson (not that Johnnie Johnson) and “Lard” Langford took off at nearly 7 PM in the evening on a strafing and recce op along the Piave River Valley. They each slung a 45-gallon long range tank under their bellies and climbed into a hazy sky. On the road between Conegliano and Codega they spotted several stationary truck convoys totalling over 100 vehicles and strafed them without any return flak. They reported three 3-tonne trucks destroyed, all “flamers, one of which blew up with a large explosion”, 20 mixed vehicles damaged, armoured fighting vehicles (half-tracks and wheeled) with more than 20 fires burning when the section left the area. When they landed back at Bellaria, it was nearly 9 PM and Lambie’s first night landing in a Spitfire.

On the 30th, he stood readiness duty with a 90-gallon slipper tank underneath for any contingency and was scrambled at around 6 PM with Pilot Officer A. D. “Dougal” Gibson to assist in an Air Sea Rescue search. They were headed just ten miles north of Ravenna where they sighted wreckage of a 601 City of London Spitfire just ten feet from shore at the north end of the Valli di Comachio Lagoons near their namesake town. After a couple of low passes they could see footprints in the sand around the downed aircraft and leading away from the wreck. Upon landing at Bellaria, they reported no sign of the pilot but believed that he was OK. The lost 601 pilot was Flying Officer Thomas J. Vose, who had suffered a glycol leak after a sortie in the Chioggia (Venice) area and was forced to execute a wheels-up landing on the edge of the shallow brackish wetland lagoon—the largest wetland complex in Italy. Vose was indeed uninjured and made it back to the squadron the following day.

Lambie photographed his buddy Jack leach inside the cockpit of this totally destroyed wrecked of a Caproni Ca-314 with Jack Leach aboard. It’s hard to tell where this photo was taken, but the time stamp puts it in March. The only two airfields Lambie was posted to in March were Gaudo and Bellaria, Since Gaudo was an Allied constructed airfield, there would be no Italian wrecks there. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

This is what the aircraft type in Lambie’s previous photo should look like when undamaged. Typical of many Italian aircraft designs of the Second World War, the Caproni Ca.314 was a beautiful looking airplane. Its retractable landing gear included distinctive wheel spats. Derived from the similar Ca.310, this Avro Anson-sized monoplane was used for ground-attack and torpedo bomber duties. It was the most extensively built Ca.310 derivative, and included bomber, convoy escort/maritime patrol, torpedo bomber, and ground-attack versions. Photo: via Pinterest

By the beginning of May, it was clear there would be little combat action left for the pilots of 417 Squadron. On the first of the month, Lambie flew one final combat sortie — a fruitless two-hour and five-minute strafing recce to Venice and then northeast towards the Yugoslavian border. There was nothing to report and no targets to make runs on, but Lambie reported that they saw Venice clearly! It was his 50th combat sortie and when he landed, it was his last. Though the next day he flew an air test and later a number of celebratory formation flights, he made no more offensive sorties.

On the same day, the squadron received orders to move en-masse to the captured enemy airfield at Treviso, 27 kilometres northwest of Venice. The very next day, they were already on the move with a convoy of staff officers, airmen and equipment under the leadership of their competent adjutant, Flying Officer Doucet, pulling out of Bellaria at eight o’clock in the morning for the 210 kilometre journey to their new airfield. Lambie does not have a flight recorded in his logbook for the move to Treviso, so he was one of the squadron line pilots who rode in a truck in the convoy, there being more Spitfire pilots on the squadron than Spitfires.

On 2 May, the day of the big move north, the Germans in Italy surrendered unconditionally. 417 Squadron along with every combat and support unit in the Italian theatre received the following message from Field Marshal Harold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis, KG, GCB, OM, GCMG, CSI, DSO, MC, CD, PC (Can), PC

May 2, 1945

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Forces in the Mediterranean Theatre

After nearly two years of hard and continuous fighting which started in Sicily in the summer of 1943, you stand today as the victors of the Italian Campaign.

You have won a victory which has ended in the complete and utter rout of the German armed forces in the Mediterranean. By clearing Italy of the last Nazi aggressor, you have liberated a country of over 80,000,000 people.

Today the remnants of a once proud Army have laid down their arms to you — close to a million men with all their arms, equipment and impediments.

You may well be proud of this great and victorious campaign which will long live in history as one of the greatest and most successful ever waged.

No praise is high enough for you sailors, soldiers and airmen and workers of the United Forces of Italy for your magnificent triumph.

My gratitude to you and my admiration is unbounded and only equalled by the pride which is mine in being your Commander-in-Chief.

H. R. Alexander

Field Marshal,

Supreme Allied Commander,

Mediterranean Theatre.

The next day, the Orderly Room staff and the Commanding Officer’s trailer, having seen the move through, set off for Treviso too. The “kites” and their pilots left at 4:30 in the afternoon, leaving a rear party to clean up their presence in Bellaria. On the way to Treviso with the Commanding Officer’s trailer, they lost “Toughie” their unofficial mascot, a Jack Russell-like terrier. Toughie was lost when he decided to jump off a truck and walk across a pontoon bridge over the Po River. At the other side he refused to get onboard again and the traffic was too heavy to waste time coaxing him back. “So”, states the Squadron ORB, ““Toughie” is probably now in the hands of his greatest enemies…. the Italians!”

The local conditions on the trip north compelled the squadron diarist to describe the scene graphically:

“considerable improvement in the people and the countryside as we advanced north of the Po River. South of the river are the heaps of rubble left by our bombers and the cheerless people who continue to exist in the shattered villages. At the great river, which seems to be the dividing line, this desolation reaches its peak. Skeletons of guns and motor transport line the banks and the bloated bodies of horses and oxen lie here and there in the stream.

Travelling north of the Po, these evidences of war gradually lessen; fewer buildings bear the tell-tale pock marks of house-to-house fighting; there are no signs of shelling, and only the obviously military target has been reduced to a pile of brick, dust and twisted metal girders.”

At Treviso, the pilots in the mess would acquire a new and unnamed mascot (above) to replace the Toughie, first dog who was lost during the move by truck convoy from Bellaria to Treviso on 2 May. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Treviso airfield, May, 1945

With their aircraft now on the ground at Treviso, the squadron sent up just four operational sorties on 5 May, these being merely a weather flight and something called an “inoffensive patrol”. The airfield at Treviso was first constructed in 1936 and became one of the more important Royal Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica Italiana) airfields in that part of Italy. It was home field to a night fighter training centre and an ever-changing number of operational bomber, fighter and reconnaissance units. It was also a transit field for aircraft en route to and from Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia. The Italians named the airfield after Giovanni Giannino Ancillotto, an Italian fighter ace of the First World War, but the never-romantic Germans called it simply Flugplatz 222. It became a busy place indeed after the cessation of hostilities, with American transport units based there along with the Spitfires of 244 Wing and plenty of aircraft staging through. Though it was a substantial airfield it did not have paved runways. The landing area was a wide, grass field (about 1465 metres by 530 metres) in the tradition of early war airfields. There were four very large hangars with paved aprons for servicing.

Upon arrival at their new home, the pilots of 417 pitched tents for temporary accommodations, but by the end of the month had commandeered space in a vacated villa a couple of miles from the field. Treviso would be their home for May and a large portion of June.

Jack Leach doffs his cap from the back of a 417 Squadron CMP after arriving at Treviso. That CMP is probably two years old but looks 20. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Having just recently arrived by convoy at Treviso, Jack Leach plants the unit pennant alongside their tents and laundry lines. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Chuck Holdway of Cedars, Quebec (now Les Cédres) on the north shore of the St Lawrence west of Montreal poses with his tent at 417’s first encampment at Treviso. The floors are not even in yet. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Newly arrived at Treviso, four Ontario pilots settle in to their temporary campsite, awaiting more formal quarters. In the foreground, Al White (left) of Toronto and Jack Leach of Windsor use a school desk to write letters back home while in the background, Vern Herron (back to us) of Toronto and Pete Helmer of Ottawa are washing up in the warm Italian sunshine. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A Visit to the Front to view the surrendered German Army

May 7, 1945

Shortly after their arrival at Treviso and with the squadron still setting up shop on the airfield, a group of 417 Squadron pilots and airmen took a day trip by truck and jeep to the front lines at Conegliano where they knew the Germans were gathering to surrender their arms and assemble for transport south to PoW camps. En route they inspected damaged Wehrmacht equipment along the roadside and when they got there spent time chatting with some of their former enemies. Here they found gratitude amongst most troops and still some degree of haughty arrogance in some officers. All the while, Lambie was there with his camera to record the scenes.

The boys (Left to right G.P. Hope, David Goldberg (C.O.) and Chuck Holdway of 417 Squadron inspect some of their handiwork — a pair of damaged Italian Autoblindo 41 armoured scout cars — on the road between Conegliano and Vittorio Veneto near Treviso. It’s not known if these were operated by the Germans as there are no German markings on them, but the Wehrmacht operated a large number of them after the Italian surrender, calling them Panzerspähwagen AB41 201s. I bet the missing tires were taken by local Italians! Photo: Donal Lambie Collection

Lambie’s friends Jack Leach, Len Dudderidge (at the wheel) and Bob Latimer park their Willys Jeep in front of a surrendered German 88 MM anti-aircraft gun after the cessation of hostilities. This had to be a great day for the men as they toured the area previously occupied by the Germans. It was late Spring and the trees were shady, the weather warm and the victory total. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Along the highway north near Conegliano, the 417 airmen inspect more damaged Motor Transport, wondering if this was more of their handiwork. There is a small group of photos from this trip that are square in format and with the name “Leslie” written on the back, leading me to believe these were additions to Lambie’s album from Flying Officer Jack Leslie, another 417 pilot from Montreal. They would have stayed in contact after the war since they were from the same town and likely shared personal photos. Photos: Jack Leslie, Donald Lambie Collection

An Italian military bus rumbles down the highway as Lambie and his friends tour the recently surrendered territory in the northeast of Italy. I spent a ridiculous amount of time on the internet trying to identify the make of this bus — Alfa? Macchi? Lancia? Opel? etc … no luck, so if anyone knows anything about Italian busses of the Second World War, please reach out to me. I need ot put my mind to rest. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Along with the surrendering Germans, came some of the few remaining tanks left to the retreating Wehrmacht including this Intact German Panther Tank with turret facing the rear. It looks in relatively good condition but its German Army markings are missing.

Out of curiosity no doubt, Lambie and some mates from 417 Squadron went to visit the PoW Camp (more like an assembly area) at Conegliano on May 7, 1945. While we celebrate VE Day on May 8, the Germans signed surrender documents in Caserta, Italy on April 29 with the cease fire effective May 2nd. Just weeks before, the men had bombed enemy targets in Conegliano about 40 kilometres north of the centre of Venice. Lambie notes in his caption that the “Hun officer - Iron Cross - shows dejection.” He describes the others in the photo with their back to the camera: “In the group with back towards the camera – Hun Capt. (Arty) Iron Cross acting as Adjutant, ginger haired and very precise — Tall chap - a colonel”. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

These were very experienced and blooded German soldiers. Lambie captions his photo, describing the officer walking towards him: “Another Iron Cross chap — getting ready for a trip to the south. One Capt. stripped himself down to an ordinary private in so-called disgust towards those who surrendered.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Another photo at Conegliano on May 7. After years of hearing about the Master Race and the might of the German Army, there was disdain in Lambie’s voice as he writes: “One of the cowed Supermen, awaiting removal to the south… They were as happy as hell to be our prisoners rather than the Russians.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Clinging to the shade of a building in Conegliano, German soldiers await transport south to a proper PoW processing camp. Lambie describes them as “Very docile and co-operative.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie shows a lack of sympathy for the gathered German prisoners stating… “How soft we are!! They were extremely well treated compared to the treatment they justly deserved.” I suppose it’s hard to find empathy for troops that were recently responsible for killing three friends. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Wing Thanksgiving Church Parade

Treviso, May 13, 1945

From 10 to 12 May, Lambie flew again, but not for offensive missions. These last flights were practice sessions for an upcoming Desert Air Force flypast over the city of Udine, scheduled for 26 May. On three flights over three days he practiced 12-plane formations of vics and lines-astern led by three different men: Karl Linton, David Goldberg, and Nick Nickerson.

The squadron took a break on Sunday the 13th for a large wing-strength Church Parade, a “square bashing event” held on the airfield grass with everyone turned out in their finest tropical uniform. The veteran and legendary Tony Bryan had the honour of leading 417’s airmen onto the field. It was the first Sunday since VE Day on the 7th of May and there was much to be thankful for. The squadron operations record book states:

Spit and polish for the Wing Thanksgiving Church Parade. It’s been a long time since the last square-bashing for most of the squadron but all in all it was an excellent turnout.

Each airman was given a program entitled “A Service of Thanksgiving for Victory — Thanks be to God who giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ”. It says a lot about that time that no other religious groups such as Jews were accommodated, even though the Commanding Officer, Squadron leader David Goldberg, DFC and other Wing pilots were Jewish (Lambie’s Montreal friend Rudy Weinmeister of 241 for instance).

Getting the Spitfires looking spiffy for the big “Wing -Do” — a Desert Air Force mass victory fly-past at the end of May — Flight Sergeant “Mac” McCloskey, one of the ground crew, with paint in hand appears to be touching up the yellow propeller tips of this Spitfire (AN-P) at Treviso. Note the covers over the tires to prevent sun and oil damage and the custom “P” marking on the air intake. There would be 39 squadrons participating in the flypast and David Goldberg wanted his Spits looking sharp. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Flight Lieutenant Tony Bryan, DFC leads a squad of enlisted airmen through the Treviso airfield motor transport section on the way to the mass VE-Day church service held on the airfield on the Sunday following VE-Day. A year before this day, Bryan had been shot down over France and spent several months with the French Resistance before making his way back to his unit. Now, here he was leading a formation of victorious airmen onto an Italian airfield near Venice to celebrate an end to the horrific war that took so many of his friends. Many memories were brought back to the light this day no doubt. Photo: Jack Leslie via Donald Lambie Collection

417 Squadron officers in the squadron motor pool line up for a parade onto the airfield for Sunday service following VE Day, May 13, 1945. Lambie is fourth in the front row, Jack Leach to his right, Karl Linton at this end of the front row, Bob Latimer at end of back row. Photo: Jack Leslie via Donald Lambie Collection

Square Bashing. Enlisted men, NCOs and officers of 244 Wing (No.s 92, 145, 241 and 601 RAF with 417 RCAF) form up on the grassy infield of Treviso airfield for Sunday Service. The airfield is crowded with the wing’s Spitfires and American C-47 Skytrain transports. Photo: Jack Leslie via Donald Lambie Collection

Lambie turns his camera to the right to get a full picture of Treviso’s sweeping grassy infield with more 244 Wing Spitfires and other aircraft. Photo: Jack Leslie via Donald Lambie Collection

There are a number of photographs in Lambie’s album that show him and others at a seaside beach at the bottom of high cliffs. I am not certain when this visit to the Adriatic Sea happened (or even if it was the Adriatic), but assume it was sometime after VE Day when they had more time to enjoy themselves, possibly in June. In the background we see beach cabanas, a couple of man-made tunnels, likely leading down from the clifftop. It looks as if Lambie is standing on the balcony of a house, restaurant or hotel. Any help identifying this location would be greatly appreciated. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The men of 417 Squadron at the seaside. Note the stocking tan lines on the man at right and the man sitting down on the deck. With such a distinct location — black sand beach, shear cliffs and tunnels — you would think this place would be easy to identify. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Pilots of 417 Squadron cavort in the surf on the black-sands of some Italian beach. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

“Our Castle” May 18, 1945

At first, the squadron’s accommodations at Treviso were spartan, consisting of a tent without a floor. After a week or so, the pilots had upgraded their digs with wooden floors and wash stands, but things really took a step upwards when the squadron commandeered a large house and began to turn it into an officers’ quarters and club. The squadron diarist who maintained the Operations Record Book made this entry on 18 May: “We’ve located an abandoned castle some two miles from our present site and aircrew and officers are all busy moving the officer’s mess to the new location. If we can scrounge a pump and a motor it will be possible to use the grandiose ablution facilities connected to each suite.” Since the pilots of the squadron were no longer standing readiness duty or flying all that much, they could take advantage of a big mansion two miles from the airfield.

George “GP” Hope poses with veteran Spitfire pilot Warrant Officer Leonard John Duddridge in the garden behind what Lambie calls “Our Castle”. Duddridge, from Hanley, Saskatchewan, joined the squadron for the last month of the war, but was a combat veteran with two previous tours to his credit. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Leading Aircraftman Leonard Duddridge (left) from the previous photo poses with his siblings Gladys and Leading Aircraftman Lewis when he was in training to be a pilot with the RCAF. The Duddridge family was from the small farming community of Hanley, Saskatchewan. The two boys enlisted at different times (Lew started a year earlier and took courses in aircraft mechanics), but they were posted together to No. 7 Initial Training School, Saskatoon. They completed their Elementary Flying Training together at No. 6 EFTS and then they were together for their Service Flying Training at No. 10 SFTS, Dauphin, Manitoba. Len flew Spitfires on Malta with 94 and in North Africa with 238 Squadrons, RAF before coming to 417 Squadron while Lewis flew Lancasters with Bomber Command over Europe. In a fine example of 6-degrees of separation, Len Duddridge had flown from HMS Eagle on Operation Style in June 2, 1942, the very same operation in which Pilot Officer David Rouleau was killed. On that day, Duddridge and Rouleau were both in a formation of nine Spitfire pilots trying to get to Malta when they were attacked by Messerschmitts. Duddridge survived, Rouleau did not.

One lived, one died. On June 3, 1942, nine unarmed Spitfires launched from HMS Eagle were approaching Malta after a long flight when they were set upon by Messerschmitts based at Pantelleria. Four of the pilots were shot down and killed, the other five struggled on and landed on Malta. David Rouleau of Ottawa, the man on the right, was one of the four who were killed. He lived just a few blocks from my home. Len Dudderidge, the man on the left, survived and continued to fight for another three years and ended his career with 417 Squadron. Photos via Dudderidge and Rouleau families

Absolutely my favourite photo in the collection — 417 pilots getting drunk at the “castle” mess at Treviso, Italy, about 26 kilometres north of Venice. Treviso was where the storied Second World War history of 417 Squadron came to an end. They soon lost their Spitfires and disbandment was not long after. It was the time of victory in Europe and the boys looked for reasons to let their hair down. Left to Right: Flying Officer Bob Latimer, Flying Officer George Proud “GP” Hope, Flight Lieutenant Karl R. Linton, DFC, Flying Officer Ted Whitlock peeking in from the right and Jack Leach at the back. Karl Linton in the white shirt had joined 417 Squadron mid-February after returning from leave in Canada. Prior to that he had flown with 416 Squadron in England followed by 11 months with 421 Squadron, all flying Spitfires. This was essentially his third tour. Linton, from Plaster Rock, New Brunswick, died in 2010 in Halifax, Nova Scotia at the age of 87. After the war, Ted Whitlock attended the University of Toronto and earned a degree in Political Science and Economics . Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Sadly, six years after Lambie took the photo of his partying comrades at Treviso, George Hope was killed in a flying accident near his home town of Windsor, Ontario. As a member of the RCAF Reserve, he was flying a de Havilland Canada DHC-1 Chipmunk when he was overwhelmed by bad weather. Image via newspapers.com

According to newspaper reports at the time, the aircraft went down in “a welter of stormy, drizzly weather which cut visibility to nothing.” Chipmunk CF-CXF was a civilian-registered aircraft purchased by the RCAF and loaned to the Royal Canadian Flying Clubs Association. He was on a routine cross-country training flight when he went down. Hope, as a member of the RCAF Reserve, was one of 36 reservists taking part through the Windsor Flying Club in Operation Chipmunk… a scheme to give former combat pilots refresher courses. Image via Newspapers.com

Flight Lieutenant Karl Linton, DFC who was a flight leader with Lambie’s 417 Squadron and who is seen in the drinking photo above, had an exceptional career. After arriving overseas in March of 1942 and attending a Spitfire OTU, he spent eight months posted to 416 Squadron followed by another 11 months with 421 Squadron before a seven month posting as a staff pilot for No. 83 Group Support Unit, RAF. Then, after a well-earned trip back to Canada, he joined up with 417 Squadron in February of 1945. In 2003 at the age of 80, he wrote and published a memoir of his flying experiences in the Second World War called Lucky Linton—A Second World War Spitfire Pilot’s Memoir and was recently mentioned in another Vintage News story by Stephen M. Fochuk about a one in a million event. Karl Linton of Plaster Rock, New Brunswick died in 2010 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

There a few photos of 417 officers posing for Lambie in small groups at Treviso. This was certainly the result of Lambie’s desire to remember his comrades long after they had all scattered across Canada following the war. Without his photos, some of these men might fade to obscurity. In this group, “GP” Hope (left) stands with two of the squadron’s non-flying officers — Flight Lieutenant Bob Hogg (centre), the squadron Education Officer and Flight Lieutenant Hal “Doc” Smythe, the Medical Officer (flight surgeon).

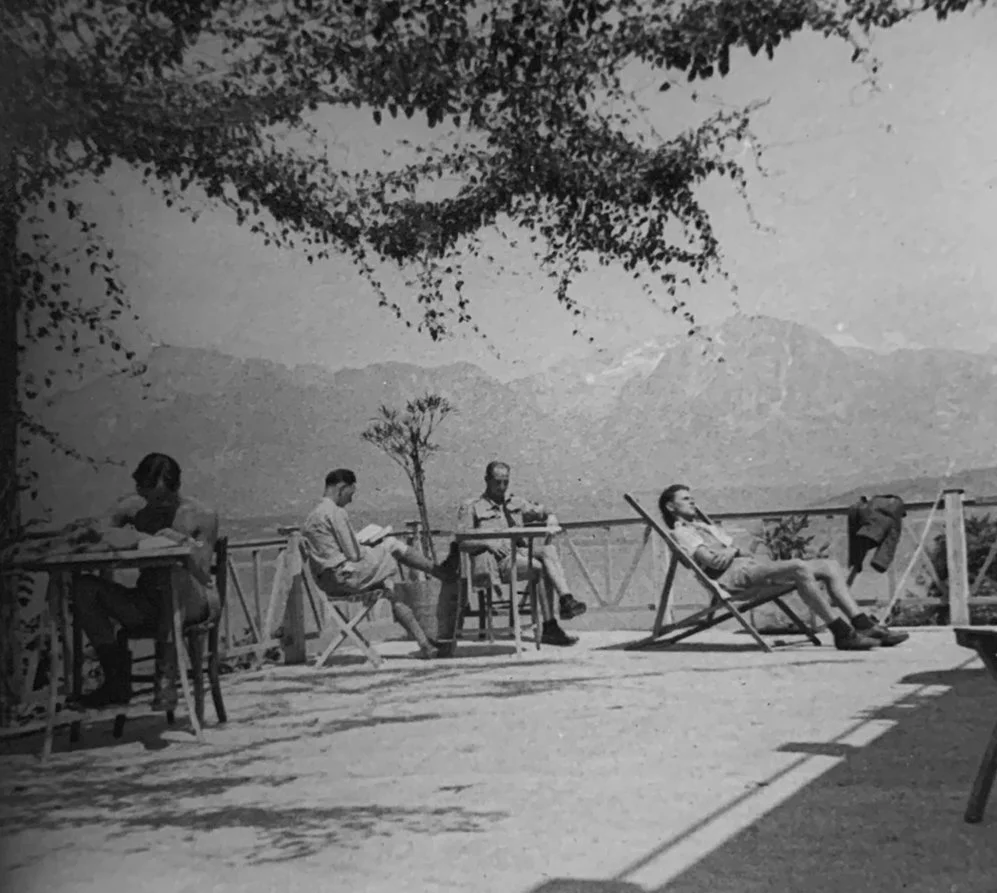

42-hour 244 Wing Rest Camp at Lago di Santa Croce

May, 1945

Sometime in late May, possibly between the 25th and 28th, some of the officers and pilots of 417 were granted a two-day pass to visit a “rest camp” in the Dolomite Mountains 55 kilometres north of Treviso. The camp was actually a small hotel and trattoria in the village of Santa Croce. The Trattoria Bolognese was situated high on a bluff overlooking the south end of the blue alpine waters of Lago di Santa Croce. The terrace there afforded a magnificent view over these waters to the craggy rise of the magnificent Dolomite peaks.

While the men were resting, swimming, boating, reading and drinking cheap Italian vino on the sun-drenched terrace of the Trattoria Bolognese, they took a couple of day trips to follow the alpine river valleys deep into the Dolomites and all the way to the Austrian border at the famed Kreuzberg mountain pass. Lambie’s photos capture these moments of pure joy that would create happy memories and act as a balm to heal years of war and loss. Through Lambie’s and other pilots’ eyes, we see the love and closeness that surround a fighting squadron, even after the war is done. These memories of sunlit alpine vistas and endless, threat-less days would abide with them until the end of their days. In many respects, these past years and these last days would determine the kind of men they would all become — worldly, reflective, and predisposed to helping others.

At war’s end, Lambie and a few 417 Squadron mates took an R and R trip up the Piave River Valley by squadron lorry to visit Belluno and the Italian Dolomite Range of the Eastern Italian Alps, then on to the Wing’s rest hotel. Here, they stop at a spectacular overlook of Lago di Santa Croce. This was in May of 1945, and the occupying German army had just recently surrendered. One can’t help thinking what this Canadian Spitfire pilot (possible Jack Leach) was thinking as he looked upon the spectacle of this Italian alpine paradise which had, until a couple of weeks ago, had been in enemy hands. The notation on the back of the photo reads: “A good view of Lake St. Croce when we had our squadron rest camp. The white house [next to pilot’s left shoulder] is where we had our “chop”.” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

With the aid of Google’s Streetview, we are able to drop into the same spot where Lambie and friends stopped to look at Lago di Santa Croce (previous photo) and the high peaks of the Dolomite Mountains. Image via Google Streetview

A composite view of a very still Lago di Santa Croce made from two of Lambie’s photographs. This seems to have been taken a bit farther along on the same road shown in the previous photo. The stillness of the lake is remarkable. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A squadron CMP truck loads gear and other 244 Wing personnel having just dropped off pilots and officers of 417 Squadron at the Trattoria Bolognese for a 48-hour rest period. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

It’s truly amazing that nearly 80 years later, the Trattoria Bolognese is still in operation in the same location, but as Bar Ristorante Bolognese. Image via Google Streetview

With the stress of daily operations over, their Spitfire flying days at an end, the pilots of 417 Squadron can truly relax. Here with the noonday sun warming them after the long winter of war and the breathtaking Dolomites rising over the lake, they read and write letters home. Two of the officers are mentioned in the backside caption, but not identified among the four men in the photo. They are Flight Lieutenant Larry Doucet, the squadron’s admin officer and pilot Flying Officer Chuck Urie. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

This is the magnificent view that Lambie and his fellow 417 pilots enjoyed while sitting on the terrace of Trattoria Bolognese. Photo: Victoria Popa, 2021

Lambie and some friends borrowed a boat and rowed their way out onto Lago de Santa Croce. Here, we are looking back towards the Trattoria Bolognese [the white building at centre right]. Officers slept at night in a concrete boathouse at the base of the hill leading down from the trattoria. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Fling Officer Charles Edward “Chuck” Holdway of Les Cédres, Quebec beams in a rowing skiff in the middle of Lago de Santa Croce. Holdway was one a relatively small percentage of Second World War pilots who remained in the RCAF after the war. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the post-unification Canadian Armed Forces. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

While at Lago di Santa Croce, the officers of 417 Squadron slept in a brutalist modern concrete boathouse by the water’s edge. Here Bill Craig and 417 Squadron Medical Officer Hal Smythe take in the sun. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

For one of their sightseeing trips while resting at the lake, the 417 boys commandeered a Fordson WOA2 Heavy Utility Car — the Second World War equivalent of the modern day Hummer and made by the British Ford Motor Company. Here, Lambie (centre) stops along the Lago di Santa Croce shore road to stretch his legs and take in the turquoise alpine lake. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A similar view of a Fordson Utility Car - the grand daddy of the Hummer and today’s SUVs. It must have been “really something” to be roddin’ around the Alps as victors in a roaring six-man Fordson with the snow-capped mountains, the alpine meadows, the turquoise lakes, the Italian welcome and the war behind you. Photo: Pinterest

After one day-trip to Belluno, the largest and most important city in the Eastern Dolomites, a group of 417 pilots stop along Strada Statale 51 at the north end of Lago di Santa Croce to stretch their legs and compare notes and souvenirs. The 417 Squadron-marked Fordson looks pretty battered and dusty. The building and facilities at right control the flow of water to Il Canale Cellina, the short canal the brings boats around the shallower north end of the lake Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

By “driving” the road from Santa Croce through Google Streetview, it was only a few kilometres to the very spot where Don Lambie and the group of 417 Spitfire pilots stopped to chat and show off their “booty”. Those young men would never have imagined that nearly 80 years later, some 71-year old man would be using something like Streetview and the internet to find the exact spot and then gaze upon it while contemplating the beautiful absurdity of it all. Photo via Google Streetview

Lambie and his friends commandeered that RAF Ford utility vehicle and took it on more than one trip up through the valleys of the Veneto/Belluno region of Northern Italy, venturing deep into alpine river gorges in the southern Dolomites. One such valley followed the flow of the Cismon River to the alpine town of Lamon where Lambie took this dramatic shot of water overflowing the dam near the Ponte Serra bridge crossing. One can only imagine the power these young men must have felt as they experienced the beauty and hospitality of a region recently freed from the yoke of Nazi tyranny. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The road and viewing areas at bottom centre is where I believe Lambie was standing when he took the previous photo. Though the “cascate” is not overflowing the dam on the day this drone shot was taken, the reservoir still releases water through spillways downstream on the Cismon. The switchback road at left climbs up out of the gorge to the alpine town of Lamon.

After literally hours of fruitless searching the internet and Google Earth, I could not find the identity of this village in the Dolomites visited by Lambie and his friends. The caption on the back of the photos simply states: “A little village in Northern Italy where a few Huns made a feeble stand. The tower and top of the steeple has [sic] been damaged as well as a few houses nearby. May 1945” Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

On a sightseeing trip from Lago di Santa Croce, Lambie and the boys drove right to the Austrian border through the mountain pass known in Italy as Passo di Monte Croce di Comelico or as the Austrians call it: the Kreuzberg Pass. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

In the same Austrian border crossing in the Kreuzberg Pass, a newer Kreuzberg Hotel stands at the same location on the highway. Image vie Google Streetview

In a photo taken by Jack Leslie, we see German bunkers ready to repel the enemy should they attempt an attack through the mountainous Kreuzberg Pass. They were never used. Photo: Jack Leslie via Donald Lambie Collection

Cut from the Dolomite granite and reinforced with concrete, the bunkers still exist today. Photo via Google Maps

Desert Air Force Mass Victory Flypast

Campoformido Airfield, Udine, Italy, May 28, 1945

After the Wing’s Sunday Service parade on 13 May, the operational flying ended and all that was left was to practice squadron strength formation flying for the upcoming Desert Air Force’s flypast at Campoformido Airfield near Udine, close to the Yugoslavian border. Here the RAF was going to mass aircraft from 39 different squadrons in a long aerial cavalcade as dignitaries looked on at the power and might of the victorious Allied air units.

The first practice flight was a 12-Spitfire formation flypast for the entire Squadron on 10 May. This was followed by five more mass formation practices of about an hour in length. They practiced 12-aircraft arrowhead formations, vics and line astern and line abreast formations. For all of these flights leading up to the DAF flypast, Lambie flew in “his” Spit — LZ923, coded AN-T. On 19 May, they joined the other squadrons of the wing for a coordinated dry-run rehearsal just for the airmen and officers of the entire wing — 417, 601, 241, 92 and 145 Squadrons. This and three more practices over the next week were led by Squadron Leader David Goldberg. The original date for the victory flypast was to by 26 May, but foul weather delayed the event. Finally, on the 28th, with long range tanks hung, the 12 Spitfires of 417 Squadron took off for Udine to join 38 other squadrons of fighters and bombers for the big show in honour of the Desert Air Force's huge contribution to Victory — in North Africa, Malta, Sicily and Italy.

After the flypast, the pilots flew back to Treviso, but the CO, Squadron Leader David Goldberg and two of his Flight Commanders, Tony Bryan and Karl Linton got to land at Udine and attend a reception.

South African Air Force Mustangs (left) of No. 5 Squadron, 239 Wing and 450 Squadron Kittyhawks led by S/L Jack Doyle take part in the DAF’s flypast on 28 May, 1945. Photos: Imperial War Museum

In the reviewing stand that day were Air Marshal Sir Guy Garrod, KCB, OBE, MC, DFC, LLD, Commander in Chief of the Royal Air Force in the Mediterranean and Middle East (Centre) with Air Vice Marshal R M Foster, Air Officer Commanding, Desert Air Force (left), and Brigadier General Thomas D'Arcy of the USAAF. Photo: Imperial War Museum

12 Spitfires thunder past the reviewing stand at Campoformido. One wonders if they were the Spits of 417 Squadron which had practiced a 12-plane arrowhead formation leading up to this fly past. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Visit to the Luftwaffe “Flugfeld” at Klagenfurt-Annabichl, Austria

May 31, 1945

At the end of May, Lambie, and perhaps some of his friends flew on a “ration run” in an American C-47 transport from Treviso to Klagenfurt, Austria — 40 kilometres over the border on the eastern shore of the Wörthersee. They landed at Flugfeld Klagenfurt-Annabichl, a recently captured Luftwaffe air base. While at Klagenfurt-Annabichl they took a look around at captured and destroyed enemy aircraft and on the return trip brought back to Italy some British and New Zealand Prisoners-of-War.

In the closing two months of the war, Luftwaffe units based there included a Luftwaffe fighter Jagdgeschwader, an elementary flying school and the 1st Courier/Liaison Squadron of the Hungarian Air Force. It had felt the wrath of Allied bombers on a number of occasions since January as the Allies pushed father north in Italy. During the last of these “visits”, on March 19, 245 B-17s and B-24s of the 15th Air Force had released 589 tons of bombs on the airfield but managed only to destroy two outdated Focke Wulf Fw 44 biplane trainers from the flying school — Flugzeugführerschule FFS A 14.

After the German surrender, all the aircraft on the field — the fighters, trainers and transport aircraft — were dragged and pushed into what we now call a “boneyard”. These were of great interest to Lambie and his friends and they inspected the alien aircraft closely.

When visiting Klagenfurt Airfield Lambie took this photo of a derelict Siebel Si 204 light transport. A satellite camp of Buchenwald was created in Halle an der Saale (Saxony province) to provide labor to the Siebel Flugzeugwerke GmbH in July 1944 and one wonders if slave labour contributed to the building of this aircraft. A Seibel 204 holds the odd distinction of being the last Luftwaffe aircraft shot down by the Allies — on 8 May, 1945 in Bavaria. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Looking for images of the Luftwaffe at Klagenfurt on the internet, I immediately came across this amazing official RAF photograph of 232 Wing RAF ground crew taking refuge from the sun under the wing of the VERY SAME Siebel Si 204 as the one Lambie shot. This reminds me of the line from the old Second World War song We're Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line. Nothing says victory like using an enemy warplane as a laundry rack. In the background at right is parked another Siebel aircraft — a Siebel Fh 104 Hallore. Image: via the Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum, USA

Another photo (not one of Lambie’s) of the boneyard at Klagenfurt in the summer of 1945. One understands the draw this sort of aircraft graveyard had for curious Canadian airmen. One of the dispersal areas is jammed with Luftwaffe Siebel Fh 104 and Si 204 transports, loads of Arado Ar 96 advanced trainers including several Hungarian Air Force examples (white cross on black square), a pair of Focke-Wulf 190s and possibly a Focke-Wulf Fw 44 Stieglitz biplane trainer buried right in the middle. We forget that Hungary was part of the Axis Powers in the Second World War and embraced an irredentist policy similar to Hitler’s and even today’s Vladimir Putin to justify invading their neighbours. Klagenfurt-Annabichl was a short-lived home base for the 1st Courier/Liaison Squadron of the Hungarian Air Force from April-May of 1945, which explains all the Hungarian aircraft in place. It was also home to a Luftwaffe “Flugzeugführerschule” or flying school for most of the war. The last school to occupy its ramps was Flugzeugführerschule FFS A 14 which in turn explains the presence of the Steiglitz trainer.

Lambie and other 417 pilots inspect a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 on the grass at Klagenfurt-Annabichl Flugfeld in the summer of 1945. Under the fighter’s wingtip at left we can make out a collection of junked German and Hungarian aircraft. The visit to Klagenfurt was likely not an official squadron-sanctioned trip but rather a curious group of friends who wanted to see a Luftwaffe base and all the German aircraft rumoured to be collected there after the end of hostilities. Klagenfurt was about 100 miles north east of Lago de Santa Croce in the Austrian Alps. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

The two huge hangars shown in Lambie’s previous photograph are still in very active use to this day, nearly 80 years after the war. The field, once known as Flugfeld Klagenfurt is now Flughafen Klagenfurt, the airport for Austria’s sixth largest city. Photo: Zacke82 via Wikimedia Commons

Treviso Transits,

June 1945

Treviso, like Udine to the east, was strategically placed near both Austria and Yugoslavia and was an important transit field for aircraft flying from the south to East/Central Europe. There were many comings and goings and Lambie was there to photograph some interesting aircraft. Here are some of those photos:

An Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 “Sparviero” [Hawk] gets refuelled by a 417 Squadron Bedford QLC fuel bowser at Treviso in May, 1945. One of the most beautiful looking [in my opinion] aircraft of the Second World War, the Sparviero was not a particularly lovely thing to hear according to Lambie who stated in the caption: “Sounds like a “clapped out” truck when it took off.” Bedford QL series trucks were often nicknamed “Queen Lizzie” for it’s QL suffix, but I can’t find reference for what QL actually stands for. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Another angle on the SM.79 reveals a post-fascist Italian roundel (red outer rings with green in centre) and tells us that it belonged to the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force. The Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force (Aviazione Cobelligerante Italiana, or ACI), or Air Force of the South (Aeronautica del Sud), was the air force of the Royalist "Badoglio government" in southern Italy during the last years of the Second World War. The ACI was formed in October 1943 after the Italian Armistice in September. Since the Italians had left the Axis and declared war on Germany, ACI pilots flew with the Allies, but never against Italian fascist troops still in the fight. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

A Royal Air Force Liberator C.IX is serviced at Treviso in June. In the background we see what appears to be the rear fuselage of another Savoia-Marchetti S.79. The one in the previous photo has a mottled camouflage while this one appears to be monotone in colour. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Another angle on the previous Liberator shows it to be KK311. The South African Air Force in Italy operated their Liberator bombers without the nose-mounted guns, and most had the normal turrets still fitted but with the guns removed. This one, as can be seen in the previous photo, has the streamlined nose fairing which is normal for the C-87 Liberator Express transport variant which carried about 6,000 lbs of cargo or up to 20 passengers. The RAF called these cargo variants Liberator C.IXs. I believe this is an RAF cargo Liberator C.IX which had, until recently been a bomber with 40 Squadron. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

In May, the war was over, but still there were many ways to meet your end. I can’t find anything on-line about what may have befallen this RAF Hudson at Treviso in June, but it does appear to be survivable for the crew. Since there are no crash vehicles or ambulances, it seems they have decided to let the fire burn itself out. Lambie was on hand to snap a number of photographs as the wreck burned to the ground. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

Another photo from a different angle shows us that the propellers are bent forward and this tells us that the engine was making power when the props struck the ground. To me this suggests an engine failure on takeoff or a ground loop. My understanding from some research is that if the tips are bent forward, they were under power, if they are bent back, the power had been pulled back. If anyone knows the circumstances of the loss of this Hudson in June, 1945 at Treviso, let us know. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

“A little Hungarian job, probably used as a Luftwaffe elementary trainer by the Horthy Miklo Co. Acquired by one of the squadrons” states the caption on the back of this photo of a commandeered civil-registered Bücker Bü 131 Jungmann. There were no Jungmanns built by a Hungarian company — this is a bit of Lambie humour as he is mocking Admiral Miklos Horthy, the de facto wartime president of Hungary, an ally of the Nazis. In October 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary had declared an armistice with the Allies and withdrawn from the Axis. He was forced to resign, placed under arrest by the Germans and taken to Bavaria. At the end of the war, he came under the custody of American troops. He was imprisoned at Nuremburg but was not indicted for war crimes (he should have been) and then, because Hungary was now a communist state under the control of Stalin, he self-exiled to Portugal where he died in 1957. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

I found a Hungarian website with a poor wartime photo of Jungmann HA-LDF flying in formation with others. Photo via https://www.avia-info.hu/

Winding Down

June, 1945

With the war over, the pace of things at Treviso had slowed to crawl. There was some flying in the first two weeks of June, but that seemed to be just one practice formation flight a day for Lambie. There were eight flights over the first 12 days of June, all of them four-ship formations led by either Tony Bryan or F/O George Chester “Lard” Langford. Lambie flew Spitfire LZ923 on all of these flights, usually as number “3” or “4” in the company of formations of other Allied aircraft like P-38 Lightnings and P-51 Mustangs as they cruised over spectacular places like Lake Garda, Venice or Padua.

On 5 June, during one of these formation practices, Vern Herron and “Dougal” Gibson collided and were forced to bale out of their Spitfires. Both landed safely.

The men were having fun and they knew their time in Spitfires was coming to an end. The last practice flight was on 12 June, and then it was time for one last Balbo and Lambie’s last flight in a Spitfire.

Through those first days of June, Lambie and the other pilots relaxed, unwound, partied a little, laughed a lot and began to truly enjoy their surroundings. It was time to visit Venice, float on the canals or maybe just play some chess, fix your kit or spend an afternoon at the club emptying some liquor bottles. The squadron diary was no longer filled with combat reports, after action reports and weather statements, but rather with entries such as this on 6 June:

“In sizing the camp up the lads have about everything that can be provided. Softball, volleyball, horseshoe pitches, swimming and a lovely 48-hour camp at a lake in the Italian Dolomites [Lago di Santa Croce—Ed.]. In addition liberty runs are laid on to all nearby cities. The biggest bind is, of course, about the Field ration, but apparently there’s nought to be done about them.”

And this entry on 10 June:

“Lazy day, sunning, swimming, church, etc. The Officer’s Mess invites Senior NCOs for an afternoon’s swimming and supper. After supper a general “pissy” [drinking party] swung into full bore.”

It was during this time in June that Lambie and some of his closest friends took advantage of the liberty transport to Venice and up north to the Belluno area in the Dolomites where they swam and lived in a lakeside hotel.

In June, 1945, Jack Leach, Chuck Holdway and Don Lambie strike a relaxed and friendly pose outside the “castle” mess and barracks they “found” near Treviso. Note the “417 Squadron” chalked on the brick next to the window, laying claim for the squadron. Photo: Donald Lambie Collection

At the “castle” gates, the Canadian boys are looking casual and confident. Note “417 Sqn.” chalked on the brick wall between Lambie and Latimer. They are (L-R) Flying Officer Charles Edward “Chuck” Holdway, Flying Officer Bob Latimer, Lambie, Flying Officer Jack Douglas Leach and Flying Officer Alfred “Al” White. There were a number of men on the squadron from the Ottawa/Rideau Valley and St Lawrence area — Latimer, Lambie, Holdway, Desormeaux, Slack and others.