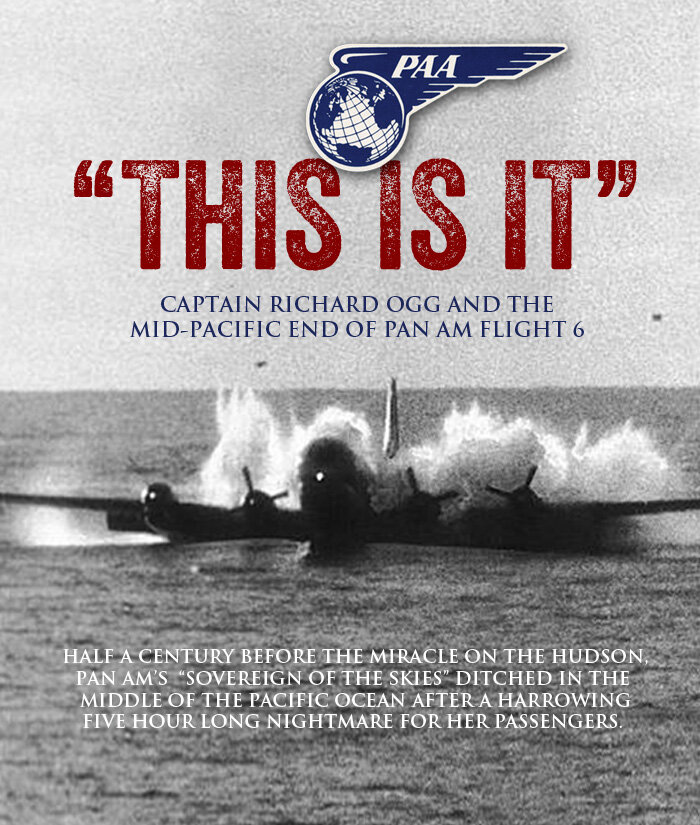

Coupable! (Guilty)

Spoiled, entitled, and manipulative, mass murderer Joseph-Albert Guay thought nothing of killing 23 people to get what he wanted.

By 1949, airline travel around the world was no longer the realm of the very rich or famous, nor was it considered dangerous by the general public as it had been in the 1920s and 30s. Airlines around the globe were expanding and adding new routes, both domestic and international. In fact, as the war was winding down, politicians like Roosevelt and Churchill and their emissaries were turning their attentions to the lucrative postwar airline trade and divvying up the planet's airspace. Much of the credit for this increased trust and affordability was built on the reputation of the great Douglas airliners — starting with the DC-3, the workhorse of the Second World War. The DC-3 (and its surplus military variant, the C-47) had revolutionized airline travel. The burgeoning world of civilian commercial aviation was built on this newfound trust in the equipment and the experience of well-trained aircrews. Then in 1949, a new terror in the skies was introduced — love-triangle bombings.

On May 7 of that year, a Philippine Airlines Douglas DC-3 took off from Daet-Camarines airport on the southeast peninsula of Luzon, bound for Manila. It exploded 60 miles after take-off and fell into the Sibuyan Sea, killing all 13 passengers and crew aboard. It was quickly determined that a bomb had exploded in the luggage compartment. In a matter of weeks, investigators would arrest six Philippine nationals in a plot to blow up the airliner to rid one of them of her husband. Two low-level criminals and ex-convicts had been hired to build and plant the bomb so that this one woman could eliminate her wealthy husband, get his estate and be free to marry her boyfriend. The story was carried on news wire services across the globe and just a few months later, another DC-3 was brought down in Québec in mysterious circumstances. It took investigators, employing the new science of forensics, just days to determine that this aircraft was also brought down by a bomb. The similarities with the Philippine tragedy would soon lead to a copycat killer and his accomplices.

Québec Airways Flight 108

At 10:40 on the sunny morning of Friday, September 9, 1949, 35-year old Québecois eel fisherman Patrick Simard was tending his weir along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, 40 miles downriver from Québec City. At 61˚ F, it was a lovely day on the water, the river making its steady way downstream to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Above where he stood, the leaves on the trees on the high bluffs that form the north shore of “Le Fleuve” from Cap Tourmente to Cap-aux-Oies were just beginning to turn—a few branches on the maples going to red and orange, the ashes yellow on their way to deep purple. Behind him ran the Canadian National (CNR) rail line from Québec City which stitched the welt of the river all the way to La Malbaie before it swung north. From where he stood, looking east, he could barely make out the pencil line that drew the south shore near St Jean Port Joli, nearly 25 kilometers away. It was a very big river.

From the southwest, he heard the throaty and rolling clatter of an approaching aircraft, polished aluminum skin glittering in the southern sunlight as it edged along the north shore. With most of his time spent on the river, he'd seen many aircraft in this area during the war, usually the small yellow biplanes they used way up river at the big airfield in L'Ancienne-Lorette or the twin-engine jobs for training navigators. Back during the war, they were all up and down the river here, winter and summer. When the war was over, he never saw them again, but bush planes often clattered up and down “Le Fleuve” and a few times a week these past few years, a big DC-3 made its way down to Sept-Îles, stopping en route at the new town of Baie-Comeau and its big pulp and paper mill. That town was growing rapidly since it was established just before the war and he'd heard there were lots of jobs to be had there— a lot more than his tiny whistle-stop fishing hamlet of Sault-au-Cochon whose few ramshackle homes clung to the rail line like barnacles. The passenger and freight trains panted, screeched and howled past his front door as they laboured their way from one north shore town to the next.

Simard watched as it approached along the high bluffs and bent its course to take it farther out over the river and angle off for Baie-Comeau some 180 miles down and around the sweep of the mighty river. Farther along the river, he noted a railway jigger and a group of five CNR section men working on the tracks at the base of the bluff, intent on their work. The silver airliner, its engines pulling hard for altitude, had just crossed to the water side of the tracks when there was a loud explosion in the sky, a large puff of white smoke blasting from the forward fuselage on the port side and whipping away in the slipstream. The airliner appeared to lurch to port and descend rapidly towards the high forested cliffs above the rail line. Simard would later tell reporters: “There was a puff of white smoke, then the plane fell into the trees with a big noise like the ripping of my tents.” Simard estimated an altitude of 500 feet for reporters, though that seems low for an airliner that is almost 50 miles from point of take-off. He went on to tell reporters that “debris of all kinds” fell from the aircraft as it plummeted and at one point he claimed he saw a human leg falling.

One of the CNR men, Oscar Tremblay, heard the explosion too—looking up just in time to see the white smoke. “I was near four other fellows working along the tracks when I heard some sort of explosion. I looked up and saw this big plane suddenly turn and head for the hills north of the railway line. It struck a big cape that sticks up near the shore of the St. Lawrence but on the inland side of the St. Lawrence.” Another rail worker, Victor Duclos, said it “made a heavy noise like a bomb.”

The explosion these six men had witnessed and the resulting horrors they would soon find as they climbed up the steep incline to see if they could find survivors, was the deliberate bombing of Canadian Pacific Airlines Flight 108 (a former USAAF surplus C-47 Dakota) on a scheduled flight to Sept-Îles in the Côte-Nord region of Québec. They had no inkling of what they had just witnessed, but it was and is still, to this day, the largest mass murder ever carried out on Canadian soil. Not until 36 years later, would this crash be far surpassed as the largest mass murder in Canadian history when an Air India flight from Montréal to London exploded over the Atlantic killing 329 passengers and crew, 268 of whom were Canadians. The DC-3 bombing was a crime so heinous and unspeakable that the judge who tried the man responsible would say at his sentencing: “Your crime... has no name”.

Earlier that day

Canadian Pacific Airlines DC-3 Dakota CF-CUA stood in the sunlight on the tarmac at the L'Ancienne-Lorette airport, a few miles to the west of Québec City, one of North America's oldest cities. It was a late summer day in a part of the world where late summer meant something—a time of increased energy and activity, lovely weather and beautiful landscapes. L'Ancienne-Lorette airfield had opened almost eight years to the day in 1941 as the home of both No. 22 Elementary Flying Training School and No. 8 Air Observers School of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The field was much quieter now that the military had left.

The all-aluminum Dakota gleamed in the sunlight, but just a few years ago, she had been covered in the dull and worn olive green camouflage paint of the United States Army, labouring in the Italian and Mediterranean war zones. She'd pulled gliders with airborne infantry, excreted paratroopers over Tunisia and humped cargo everywhere from England to Sorrento. When the war ended she was flown back to the United States via the northern route and put into storage from which she was eventually sold off to Canadian Pacific along with 16 other C-47 veterans of the war. These aircraft were refurbished and entered service on domestic routes, mainly to remoter communities in Canada. She was now in the best part of her operational life—well taken care of by experienced engineers who worked for a superb company, flown by experienced men, polished to a mirror finish and carrying passengers who, unlike paratroopers, assumed that they would still be alive by the end of the day.

An overhead shot of the airfield at L'Ancienne-Lorette during the Second World War. In September 1949, many of the ancillary buildings had been sold and moved off site. Photo: Flight Ontario

She was a on a milk run up the North Shore of the St. Lawrence River from Montréal to Sept-Îles, Québec with stops at L'Ancienne-Lorette and the new industrial town of Baie Comeau. There was an optional visit to the pulp and paper community of Forestville 100 kilometers up river of Baie Comeau should anyone be waiting there for a flight. Though she was a Canadian Pacific liner, she was operating as Québec Airways Flight 108. Her crew was also highly experienced, proud to be selected to fly with Canadian Pacific Airlines, a relatively new commercial operator, but one that was backed by the considerable reputation of its massive parent company—the Canadian Pacific Railway. The airline had begun as a bush plane operation in Western Canada just seven years earlier in 1942 and, thanks to these low-time war surplus aircraft, was rapidly expanding.

A good shot of CF-CUA taken at Bagotville, Québec in August of 1947. Two years later, the DC-3 crashed on the shores of the St. Lawrence River, killing all 19 passengers and four crew on board. According to the superb website 1000aircraftphotos.com, "This Douglas Model DC-3A-360 was ordered by the USAAF as C-47-DL s/n 41-18456 and delivered on July 13, 1942. By October 1942, it was assigned to the 4th Troop Carrier Squadron, 62rd Troop Carrier Group at Keevil, Wiltshire, England. The group had been designated as one of the units participating in the invasion of Northwest Africa in November 1942. On November 15, 1942, the group moved to Algeria and then to Tunisia in July 1943. The group then operated from bases in Sicily and Italy between September 1943 and November 1945 when it was inactivated. During this period, the group dropped British paratroopers to attack German airdromes in Tunisia in November 1942, towed gliders and dropped paratroopers during the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, dropped paratroopers in northern Italy in June 1944 to harass the retreating Germans, towed gliders and dropped paratroopers during the invasion of southern France in August 1944 and during the Allied assault on Greece in October 1944. Declared surplus, it was transferred to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. for disposal and was sold to Canadian Pacific Airlines of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada on August 31, 1946. After conversion to a civil DC-3C, the aircraft was registered CF-CUA on February 6, 1947 and assigned fleet number 280.” Photo: Guy Allard photo, Jacques Trempe Collection via 1000aircraftphotos.com

Related Stories

Click on image

Another angle by Québec photographer Guy Allard of CF-CUA at Bagotville, Québec in 1947. Canadian Pacific Airlines (CPAL) purchased 17 war surplus C-47s (military designation for DC-3—from this point forward, I will refer to CF-CUA as a DC-3) immediately after the war and operated them until the late 1950s when service on the type was discontinued. CPAL lost two of their fleet of DC-3s during that period, the other being lost when it struck a mountain side in British Columbia in 1950 with the deaths of two of the 18 on board. Photo: Guy Allard photo, Jacques Trempe Collection via 1000aircraftphotos.com

The aircraft commander for Flight 108 was Captain Pierre Laurin of Montréal, a 30-year old father who, with his wife, was expecting their second child in just a few days. He was one of the original Canadian Pacific Airlines pilots of 1942, but had transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force after a year's service with the company. He remained with the RCAF on flying operations until the end of the war. He was discharged in 1945 and rejoined the company. His experience on Transport Command Dakotas during the war put him in the command seat of CPAL Dakotas, but his co-pilot was also an experienced man. Second pilot Gordon Alexander had held a commercial pilot's license since 1936 and had accumulated over 4,000 hours flying time in his log books. Born in Ontario, he was now living with his wife and two-year old son Bruce in Verdun, a suburb of Montréal. He too was one of the early CPAL pilots who signed on in 1942 and he had been with the company ever since. According to one period news article I read, Alexander was actually made a Captain with the airline in 1946, so it's possible he was a line check pilot doing a scheduled check ride with Laurin. His wife Margaret had been an air traffic controller during the Second World War.

Dakota flights in those days, especially ones flying to smaller communities, carried a “flight engineer”. On Flight 108, this was Emile Therrien, himself a six-year veteran of the RCAF. During the Second World War, RCAF Dakotas did not fly with a crew position called “Flight Engineer”, which was a breveted aircrew trade. Second World War Flight Engineers of the RCAF were trained to manage engines, fuel and other flight systems on larger four-engined bombers like the Handley-Page Halifax, Short Sterling, Short Sunderland or Avro Lancaster. Therrien was a maintenance engineer/mechanic who travelled with CPAL flights to more remote destinations to deal with maintenance issues when they arose. He too was a married man with two sons and lived in Montréal. Photos of Therrien and his family show two young boys, Pierre (5) and Michel (4) with matching hand-knit sweaters emblazoned with a twin-engine airliner. There's no doubt Emile Therrien was proud of his job.

In the cabin, to take care of the passengers, was three-year veteran “stewardess” Mrs. Gertrude “Trudy” McKay from Lethbridge, Alberta. Trudy had joined CPAL after the death of her war veteran husband in an automobile accident three years previously. She had moved to Montréal with the company the previous year and shared an apartment with a friend who worked in the control tower at Dorval Airport where the flight had originated that morning. She had been off sick for a couple of weeks and had just returned from leave that week. She was glad to be back in the air.

In the background, ground crew load baggage aboard CF-CUA through the forward access door. This door was sometimes employed in DC-3s, allowing access to the cockpit for pilots when the cabin was blocked by cargo. The door also allowed access to a forward baggage compartment. Passengers always entered the cabin via the larger aft door which was also much closer to the ground. Photo via Canadashistory.ca

Passengers line up to board CF-CUA during a happier time. It was at this door that Trudy McKay greeted the passengers of Flight 108 half an hour before their deaths. Photo via baaa-acro.co

Already in their seats, having boarded in Montréal, were three well-dressed executives — Earl Stannard, Russ Parker and Arthur Storke from the Kennecott Copper Corporation, on their way to Baie Comeau. Trudy McKay may have talked to them briefly coming down from Montréal, but she could not have known that these three were the top executives of one of the largest mining corporations in the world. Stannard was about to retire after a long and very successful career. Parker was about to replace him at the helm of the corporation and Storke was squiring them around the company's new mining assets along the North Shore. Also onboard was 24-year old Lionel d'Allaire, a garage station owner from the village of Chutes-aux-Outardes about 20 kilometers upriver over a rough road from Baie Comeau. He was returning home after combining a visit with his sister in Montréal and a non-emergency appendectomy. Business men Cecil Humphries and Alphonso Keller, both inspectors with the Bank of Montréal, were also onboard sitting together as were two men from the Ontario Paper Company (OPC)—Bill Schoular and Ed Calnan. The company was a subsidiary of the Chicago Tribune that operated out of St. Catharines, Ontario. In 1936, the Tribune's publisher, Colonel Robert R. McCormick and OPC had built a large pulp and paper mill at Baie Comeau, which had resulted in the incorporation of the town and its recent rapid growth. One look at the mining and forestry men and bankers who boarded Flight 108 in Montréal tells us business was good on the North Shore of Québec in 1949. As well, on the plane when it landed at Québec was a young couple — 32-year old Monsieur Henri-Paul Bouchard, his wife and their infant child — sitting together on the left side just behind the forward cargo compartment. In 1949, infants were carried by their parents and were not listed on the manifest. They were returning home to Baie Comeau after a holiday with family in Sorel. Alone in one row was 47-year old Beatrice Firlotte, a widow from Broadlands, Québec on the Gaspé Peninsula near the New Brunswick border. She was coming from a visit to her sister near Montréal and on her way to Baie Comeau to see more relatives. From there, she would have to take a 40-mile ferry ride across the river and a 100-mile train journey before she got home again.

The top echelon of the massive American-owned Kennecott Copper Corporation was wiped out in the crash of CF-CUA. The men were on a tour of their Québec holdings and were to visit a titanium mine near Baie Comeau. Earl Stannard, the company's president was just weeks away from retiring. Uncertain about the future of post-Second World War copper demand, Stannard had guided Kennecott Copper towards diversification, and Parker (Vice-president of Exploration) had found a large titanium project in Québec that might serve as the flagship of the newly-diversified company. Stannard had recently been recognized with an honorary doctorate by the Michigan School of Mines at Houghton. Image via newspapers.com

Some of the faces of the tragedy. Clockwise from upper left: Stewardess Trudy MacKay, 24; A, R. Keller, Bank of Montréal inspector, 46; Cecil Humphries, Bank of Montréal inspector, 29; Madame Beatrice Firlotte, 47, a widow whose husband was killed at the Battle of Hong Kong; and Flight Engineer Emile Therrien, 22, with his wife Reine and his two sons, Michel (left) and Pierre. Photos via newspapers.com

Trudy McKay stood at the bottom of the small passenger stairway at the back of the aircraft smiling and welcoming her new passengers, most of whom were women. Coming across the ramp from the terminal was 37-year old Madame Romeo Chapadeau with her 11-month old baby boy in her arms and two others in tow — 14-year old Fleurette and 13-year old Jean-Claude. Also greeted by McKay that morning were Madame R. Durette of Baie Trinité, north of Baie Comeau and a woman by the name of Madame Rita Guay. Madame Guay perhaps looked a little bewildered to McKay as she was headed to Baie Comeau to pick up two cases of jewellery for her husband, jeweller Joseph-Albert Guay. He had convinced her just the day before to make the trip to pick up the jewellery and had rushed her that morning to the Chateau Frontenac Hotel to board Canadian Pacific's limousine to the airport. Only one man, a high school physical education teacher in Lennoxville, Québec by the name of Harold S. Pye, boarded CF-CUA at Québec that morning.

While McKay helped her new passengers to find their seats and briefed them on safety procedures, ground crews brought out a cart with the boarding passengers' luggage and a few express parcels being sent on to Baie Comeau and Sept-Îles. The cart was pushed to the open forward access door on the left side of the fuselage behind the cockpit and bags and parcels were handed up to Emile Therrien standing at the top of a steel frame stairway. One particular package wrapped in brown paper which had arrived at the last minute was marked “FRAGILE” but seemed pretty heavy to Therrien. He stowed it carefully along with the new suitcases. The flight was running a bit late this morning, so he hurried to complete this task before shutting the door. The ground crew pulled the stairways away from the aircraft and stood waiting for the pilots to signal “chocks away”.

Laurin and Alexander were just stowing their paperwork and only just commencing engine start when their scheduled 1020 start time rolled around. The engines were still warm from the Montréal to Québec leg, so everything came up to the numbers right away and the pilots gave thumbs up to the ramp attendant — no more than ten minutes late. Not so bad in a time when airline passengers weren't jaded and entitled as they are these days. A few minutes later at 10:29, they lifted off and banked over Québec itself, passing over the historic walled city, the green and angular Citadelle and the fairytale Chateau Frontenac perched on the high cliffs above Basse-Ville. It was a beautiful morning to be in the air. To their right, the ferry to Lévis churned up the fast-flowing waters of Le Fleuve St. Laurent, while tug boats were pushing a “laker” alongside the massive grain elevators at La Pointe-à-Carcy. As they headed northeast, they flew along the north side of Île d'Orléans which split the St. Lawrence into two channels. To their left rose the hulking 2,650-foot height of Mont Ste. Anne, to the right was Île d'Orléans and the broad south channel of the river. At about this point, Captain Laurin received a radio message from the CPAL office at L'Ancienne-Lorette telling him he wouldn't have to land at Forestville en route Baie Comeau. Receipt of the message was confirmed by the cockpit crew. It was the last word heard from the flight.

They flew on, keeping the high bulk of Cap Tourmente off their left wingtip and then followed the steep and looming bluffs of the North Shore down river. Soon they would angle out across the great river itself on their way to Baie Comeau. No doubt, passengers were enjoying the view on either side as the fall colours this far north were just beginning to turn. In the cockpit, Laurin and Alexander kept an eye out for the many vees of Canada and snow geese that seamed the sky in these parts and in this season. Behind the cargo compartment, Henri-Paul Bouchard likely leaned back so his wife, holding their baby, could get a better view. Two more hours and they would be home.

In front of them, in the cold darkness of the cargo compartment, inside a tightly wrapped package marked “Fragile”, the minute hand of an alarm clock clicked one last imperceptible tick towards 10:40 and a circuit was made complete and a dry cell battery sent a pent-up electrical charge through the new connection along a short length of wire to a small detonator and then everything went white for the Bouchard family.

The Mile-40 marker on the Canadian National Railway line along the St. Lawrence River marks the distance from Québec City along the rail line. It was just above this spot, high in the forested and steep bluffs that Flight 108 met its end. For those of our readers who ski in Québec, this is just eight kilometres upriver from Le Massive de Charlevoix, one of the most popular ski resorts in Eastern Canada and 20 kilometers downriver from the Cap Tourmente National Wildlife Area. Photo: jpfil/mywhc.ca

Aftermath

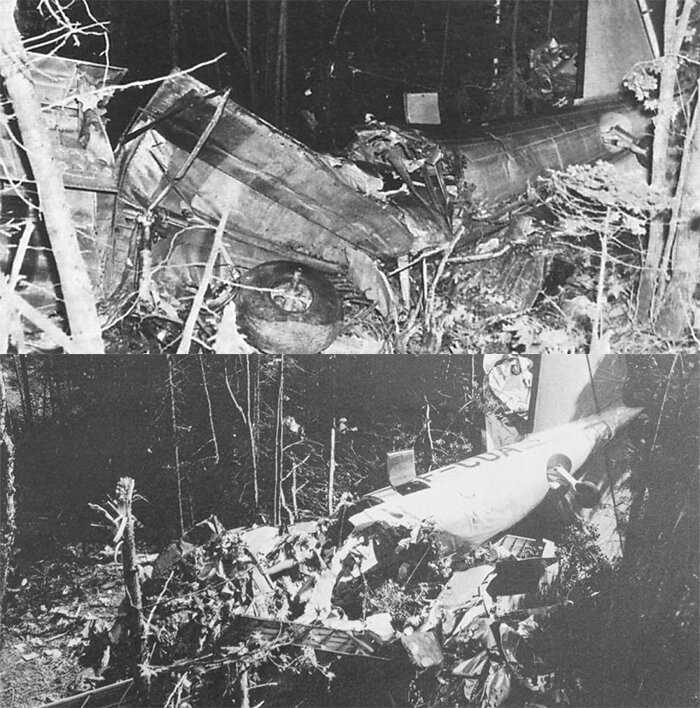

For the few witnesses to the fate of Flight 108, it must have been hard to understand what they had just seen—a shining airliner suddenly lurch in the sky, emit a cloud of smoke and debris and then dive to the left, level out a bit then fall almost vertically into the steeply sloped and forested flank of the Cap Tourmente bluffs high above them. But it didn't take them long to react. Oscar Tremblay and his crew ran down the rail line and then entered the heavily wooded slope. Groping their way through dense and tangled undergrowth, they climbed toward the spot where they saw the aircraft enter the canopy above them. It would take Tremblay and the other four men the better part of an hour to make their way nearly 2,000 feet up to the remains of CF-CUA. Fully expecting the crash site to be engulfed in flames or at least a smoking ruin, they were surprised to see the shattered and broken remains of the DC-3 and its passengers and no hint of a fire, though the air smelled of high-octane aviation fuel. The birds were back chirping in the trees as if 23 lives had not just been extinguished here. Looking at the surrounding damage to trees and the distribution of the wreckage, it was clear that the airliner had come down almost vertically. They had no idea of the cause, but it is curious 70 years later how a large aircraft fully loaded with fuel and brought down by a dynamite bomb would not burn in some way. There is no point in describing what they saw when they came upon the site, though this was covered in gruesome detail in newspapers during the day and in stories about the event over the years. Suffice it to say that the horrifying images would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Rescuers comb through the twisted wreckage of CF-CUA to remove the remains of crew and passengers. Photo: baaa-acro.com

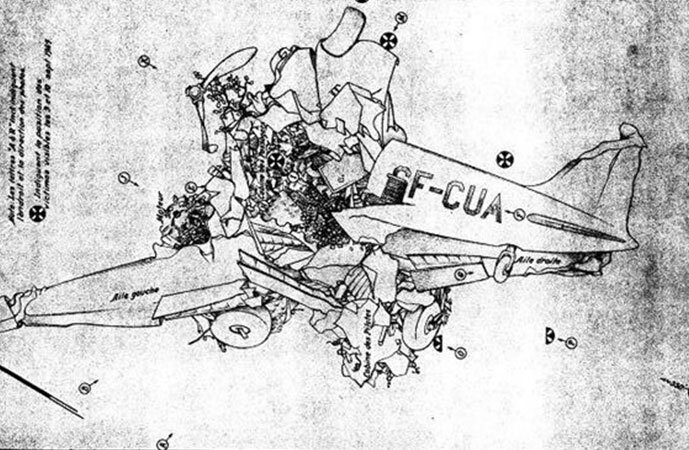

A drawing from photo reference made by investigators of the arrangement of the wreckage. The six black crosses indicate where some victims were found while the other open circles (A-R) indicate location and direction of the investigators photographs taken at the site. Most of the victims were found sandwiched between rows of seats at the center. At the bottom, between the tires, an inscription reading Cabane des pilotes indicates the position of the cockpit. This where Laurin and Gordon were found. Port and starboard wings are also labelled (Aile gauche, Aile droit).

A section of the fuselage stands in the forest high above Sault-au-Cochon. The straight edge of the upper boundary of this piece and the painted lettering tells us it's the port fuselage wall just to the left of the passenger door. Photo: baaa-acro.com

Photos of the wreckage of Canadian Pacific Airlines Flight 108 in the deep forested area near the tiny Québec hamlet of Sault-au-Cochon (literally “Pig Falls” in French). Photo: baaa-acro.com. Photo: pinterest.com

Within hours, rescuers and Québec Provincial Police (QPP) were on site, combing through the wreckage and beginning the gruesome task of collecting the remains of passengers and crew. Early responders were shuttled to Sault-au-Cochon using a motorized railway scooter called a “jigger”. Police had mounted a guard at the site within four hours and a rough 3-foot wide trail to the site from the rail line was hewn out of the densely forested slope. Eventually the recovery team, investigators, insurance representatives, more security, and even coffins were brought to Sault-au-Cochon on a special four-car train from Québec City. While there was a road that ran roughly parallel to the bluffs high above the site of the crash, it was twice as difficult to descend to the site as it was to ascend from the rail line that ran along the shore. According to the Ottawa Journal, to get to the site from the highway, it was “six or seven miles of thick bush, streams and hills”. Despite this, eager reporters, curious citizens and desperate relatives of the passengers drove from Québec City, parked their cars on the road and tried to climb down to the crash site. Among them was a tall, thin man named Joseph-Albert Guay and his two brothers-in-law. Guay appeared visibly distraught and desperate to find his wife Rita. Her brothers accompanied him as he made his way down the precarious slope. By this time, police had cordoned off the entire crash area to keep the wreckage as undisturbed as possible and would not let anyone, including the theatrical Guay and the grieving Morel brothers near the site.

News of the crash spread across the world on the wire services, appearing in evening headlines in Canada that same day and all over the world by the following morning. Using the passenger manifest from Canadian Pacific, men set out to account for all 21 passengers and crew as well as the two infants whose names were not included on the list. They could account for only 22 of these humans, with the body of passenger Henri-Paul Bouchard still missing. The fact that he was sitting closest to the location of the blast, would lead some to briefly speculate his involvement.

According to one report I found in the Montreal Gazette (Sept. 12), Tarrence “Terry” Flahiff, an executive of Québec North Shore Paper Company, was on the flight from Montréal and was supposed to continue to Baie Comeau, but got off in Québec City. He had been persuaded for unspecified reasons to get off the ill-fated aircraft by his wife, the daughter of Chief Justice Albert Sevigny, the judge who would soon preside over the trial of the man who masterminded the bombing (for those aficionados of Canadian history, Judge Sevigny was also the father of Pierre Sevigny, the Conservative cabinet minister who, 10 years later, would be caught up in the Gerda Munsinger affair). As they were still looking for the remains of the 23rd passenger, Flahiff had thought that perhaps they were looking for him. According to the Gazette story, Flahiff made his way to the site (likely on the special train) and climbed the 70-degree slope of Cap Tourmente to watch the recovery. It's possible that, Bill Schoular and Ed Calnan, the two pulp and paper executives aboard the flight were his associates. In digging a little further, I learned that Flahiff was a close family friend of Benedict “Ben” Mulroney, an electrician with the Québec North Shore Paper Company. Benedict was the father of future Prime Minister of Canada, Brian Mulroney.

The Montreal Gazette headlines a few days after the downing of CF-CUA carried no indication as to the diabolical reason for the crash. That news would soon rock Québec and indeed the world and turn the accident scene into a murder scene. The main photo used for this front page is actually an airline promotional shot taken in British Columbia. The aircraft's registration (CF-CRW) has been partially and crudely obscured so as not to confuse readers. CF-CRW would itself would be damaged beyond repair in a crash in 1978 in what is now Nunavut Territory — luckily with no fatalities. The inset photo depicts the pilot of CF-CUA, Captain Pierre Laurin of Montréal, a Second World War RCAF veteran. Image via newspapers.co

Canadian Pacific, as can be imagined, was anxious to absolve both their equipment and their crew in the disaster, and immediately sent investigators to the site. Such was the speed of their analysis of the wreckage that on the very next day, September 10, 1949, headlines appeared across Canada with a probable and, as it turned out, actual cause of the destruction of Flight 108. The Ottawa Evening Journal ran with the headline “Baggage Blast May Have Crashed Plane—Possible Disaster Cause, Find Plane Assemblies in Good Order”. Though the CPAL investigators would not disclose the precise results of their preliminary investigation, they stated in a press release that “Early inquiries by line officials reveal no explanation of the accident although the possibility of an explosion in the luggage is not ruled out.” In order to preserve public trust in airline travel in general and in their airline in particular, Canadian Pacific Airlines put every effort into an early determination of the cause.

Also, on the 10th, the Ottawa Journal reported that:

“The inaccessibility of the crash scene also placed obstacles in the way of arrangements to retrieve the remains of the victims. The first attempt to carry the bodies down the hill was made today.

The disposition of the bodies and plane wreckage was left untouched until white-haired Coroner Paul V. Marceau arrived by scooter from St. Joachim and trudged up into the hills after nightfall for his inspection.”

Once the site was photographed, remains were extricated from the layers of crushed seats and the arduous task of getting them down the steep and densely wooded slope began. Bodies were tagged, wrapped in heavy canvas shrouds and loaded on a horse-drawn sled for the slow and arduous trek to the waiting train nearly a mile below. According to the Gazette, they worked by “the light of the bright autumn moon” to get the last bodies out. Boxcars with coffins awaited on the rail line down by the river, and once the remains of the 22 identified victims were carried down the dangerous and densely-treed slope, the train bore them upriver to Québec City where they were taken to the morgue for further identification by relatives.

On September 12, three days after the crash, the Montreal Gazette reported that: “Before the bodies of the 23 victims of the third worst air crash in Canada's history, at Sault au Cochon, were removed Rev. Rosaire Veilleux, parish priest of St. Joachim, offered prayers for the dead. A special crew of workers then carried the bodies down the steep mountain to a special train bound for Quebec City.” Here we see the men loading one of the bodies onto the train that waited on the tracks below the crash site. Image via Montreal Gazette/newspapers.com

The body of the last victim, Henri-Paul Bouchard, was still not found. In a strange twist, a body of a man was discovered the next day (Sunday) floating in the St. Lawrence River near Sault-au-Cochon and the assumption was first made that this was the missing Bouchard. The fact that this body had no injuries was irregular and it was soon determined by relatives that it was not that of Bouchard. This body would later be identified as that of a stowaway from a Portuguese ship who, with another, had jumped from the railing of their freighter on the St. Lawrence, hoping to swim ashore and enter Canada illegally. The speed and icy temperature of the river had clearly overcome them both and they had drowned.

Within a few days, remains were released to families and the sad process of burying the victims began. One particular story in the Montreal Gazette on September 14 underlined the utter depravity of the tragedy when it described several of the funerals that took place in Québec City:

“Three hearses carried the bodies of the Chapadeau family, Mrs. Romeo Chapadeau, 37, her daughter Fleurette, 14, a son Jean Claude, 13, and an 11-months-old baby boy, to a service at St. Jean Baptiste Roman Catholic Church.

Mrs. Chapadeau and her infant were buried as they were found in the plane's wreckage — the mother clasping the two [sic] in her arms. Both were carried into the church in a single coffin.

Capt. Pierre Laurin, 30-year-old pilot of the Canadian Pacific Airlines plane was given funeral services in St. Martyrs Church, while Mrs. J. A. Guay's rites were held at St. Roch Church.

Despite a heavy rain, crowds watched the funeral processions.”

At Rita Guay's funeral in Saint-Roch church on Rue Saint-Joseph, her husband, Joseph-Albert, put on a tearful show of grief, and according to a 1953 story in The New Yorker, “bought a wreath in his daughter’s name, and as his own tribute purchased a five-foot cross of red roses with a heart of white roses at the center, which bore the inscription “From your beloved Albert.” A lot more about Guay a little later.

By Thursday 15, September the Montreal Gazette, based on speaking with Frank Melville Francis, one of the investigators for CPAL, reported that:

“... examination of the plane wreckage eliminated as the cause of the wreck “almost all sources” associated with functioning of the plane or its equipment.

He said this examination indicated the explosion was concentrated in the luggage compartment on the left side of the plane between the passenger section and the cockpit.

The witness [Francis] said the blast smashed through the floor of the luggage compartment as well as the walls of the plane.”

On 16 September, more than a week after the crash, Bouchard's remains were finally found just 300 feet from the wreckage by a search party made up of family and friends. No reason was given how Bouchard was missed during the official search which had lasted for days.

Canadian Pacific Airlines executives examine a piece of the wreckage of Flight 108 on September 26 at the Chateau Frontenac. Left to right: Chief Pilot Herbert Hollick-Kenyon (early aviation pioneer and member of Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame), Director of Maintenance Engineering Albert Hutt (also a member of Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame) and Frank Melville Francis, an aeronautical engineer with Canadian Pacific (who would go on to become Vice -President of Canadair). Photo via Pressreader.com

Shortly after the recovery, and operating on the theory that something had exploded in the forward luggage compartment, CPAL officials, The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and the QPP began to narrow their search. That compartment just ahead of the Bouchard family contained only the luggage and parcels that were loaded at L'Ancienne-Lorette. There were very few packages that were shipped on the flight to Baie Comeau, and investigators began to focus in on the heavy package that a mysterious and nervous woman in black had dropped off just before the flight. The identity of the woman was not known at first, but a taxi driver remembered driving her to the airport and waiting for her as she carried a package into the cargo office of CPAL. He claimed the woman had been overly careful with the package and had admonished him about his driving. He was able to take police to the neighbourhood where he picked her up and when she was eventually spotted emerging from an apartment building, was able to identify her. Police questioned the woman whose name was Marguerite Pitre. She told the police that her friend Joseph-Albert Guay had asked her to deliver the heavy-yet-fragile parcel to the airport and put it on the flight to Bai Comeau, the same flight on which he had just purchased a ticket for his wife whom he had pressured to go. Pitre claimed she did not know what was in the package and had thought it was a religious statue.

The bumbling Guay had also been flagged when, just three days after the explosion, he tried to collect on a $10,000 insurance policy he had taken out on his wife the morning of her death, as well as a previous $5,000 policy he had in place since their wedding in 1941. When police went to arrest Pitre at her home, they found her semi-conscious following an overdose of sleeping pills provided for her by Guay who had convinced her she would be blamed. Pitre would survive her overdose, but attempted suicide was illegal in those days, and soon she would be jailed and tried for that crime.

A triangle of love and a circle of evil

Joseph-Albert Guay was born in 1918 in Charny near Lévis, across the river from Québec City. The family subsequently moved to Québec City where grew up in one of its roughest neighbourhoods (at the time) known as Basse-Ville—at the river's edge below the looming magnificence of the Chateau Frontenac Hotel. A neighbour of Guay's, Roger Lemelin, who went on to considerable fame as one of Québec's best-known and most-loved novelists, called the people of Basse-Ville “the mud of society.” For most of his life Guay was a small-time hustler with a high opinion of himself. He was a charmer and manipulator who like to dress sharply and put on an air of importance far exceeding his station in life. In French-speaking Québec where double-barreled first names were the norm, he took to calling himself J. Albert Guay because he felt it sounded classier than Joseph-Albert and the just kind of mysterious name someone from the higher echelons of society might have. According to a 1953 story by E. J. Kahn in The New Yorker, he had an ambition to become a singer and an orchestra leader. Oddly, I could find no record in the many newspaper articles from the day that indicated he had any abilities in this area. In his late teens and early twenties though, he had many hustles going on, including selling watches to co-workers. During the war years, the twenty-something Guay took a job at the massive government munitions factory known as L'Arsenal de St. Malo in the Saint Sauveur neighbourhood of Québec City. While working there, he had many side hustles including selling watches of dubious quality and provenance to co-workers. In his story in the New Yorker, Kahn wrote: “At sixteen, he was a familiar figure in pool halls, where he earned a dollar here and a dollar there by selling watches and jewelry, on commission, to other hangers-on. ... He amplified his wages [from the munitions factory-Ed], which were forty dollars a week, by selling jewelry to other employees in the arsenal; he did well enough to buy a car, and he was considered a dashing figure by the young ladies in the factory.” The munitions factory at St. Malo employed hundreds of young women as well as young men like Guay seeking deferment from the “Anglo” war. He put a lot of effort into his image, dressing in fancy suits and driving about the narrow streets of Québec City in his big Mercury. This air of importance paid sexual dividends in August, 1941 when he married a young woman named Rita Morel who also worked in the armoury.

In the words of Pete Mitchell, a.k.a. Maverick, the munitions factory where Guay worked was a “target-rich environment”. It was here that he met and courted a shy woman by the name of Rita Morel. The hundreds of women and their male managers were employed in the assembly of small-calibre ammunition for Allied use overseas. Photo: Archives de la Ville de Québec -Fonds Commissariat de l'industrie; 21572.

Albert Guay in happier times with his bride Rita Morel. Photo: via Pinterest.com

After their marriage, Guay and his bride Rita took up residence in the Saint Sauveur neighbourhood of Québec City — a step up from the Basse-Ville in class, but still a working-class neighbourhood bordering on the railyards and industrial areas such as the munitions complex. In 1945, the couple had a child— a daughter named Lise. With the end of the war, the Guays found themselves out of work at the munitions plant, so Albert decided to turn his side hustle into a full-time business. He set up a jewellery and watch repair business in his neighbourhood. From the outset, business was as shaky as Guay's business practices. He had plans to move his business far down river to Sept-Îles or Baie Comeau where the new and massive pulp mills and mines were paying good salaries to men willing to live far from the major centres. According to the Montreal Gazette, reporting after the bombing, “It was at Seven Islands [Sept-Îles] that Guay was reported to have planned to move his jewelry and watch business. On three previous attempts, business was not successful and he was forced to close his store, making frequent trips between Quebec and the North Shore with his wife and four-year-old daughter.”

Guay, seen here with his one-year old baby daughter Lise in 1946, thought nothing of killing three other innocent children to get what he wanted. Photo via The Ottawa Citizen

In addition to money troubles, Guay was not happy with his wife's new and complete focus on little Lise. He eventually reverted to his philandering ways and was soon conducting a liaison with a 17-year old cocktail waitress from a club in Québec City by the name of Marie-Ange Robitaille. The details of this affair are both sordid and lurid and deserve only a cursory glance. Robitaille, who knew exactly who Guay was and that he was married, had claimed to be 19 when speaking with friends who saw her with the older man. After a year or so, Guay began calling on Robitaille at her parents' home several evenings a week. When he visited the Robitaille home, the married Guay claimed his name was Roger Angers and that he was single. He presented Marie-Ange with a ring and promised her he would leave his wife and get a divorce. Eventually, Rita found out about the affair that everyone else in town knew about and confronted the teenager at the Robitaille home in November of 1948. After a huge scene, Robitaille was kicked out of the house, whereupon she asked Guay for help. He set her up in a rooming house run by Maguerite Pitre where he continued to visit her.

Albert Guay had been having an illicit affair with teenage cocktail waitress Marie-Ange Robitaille (above) of Québec City and wanted to divorce his wife to marry the Lolita-esque girl. In decidedly Catholic Québec in the 1940s, this was never going to happen. In lieu of a legal divorce, Guay opted for the killing of 23 innocent people to rid himself of his wife

Albert Guay and teenager Marie-Ange Robitaille taking in a cabaret during their tempestuous affair, while Guay's wife was at home with their four-year old daughter Lise. Photo via newspapers.com

By the early summer of 1949, Rita along with Lise, had moved in with her mother (though Guay continued to stay with her there) and Marie-Ange Robitaille had cut off relations with him. He subsequently threatened his mistress with a gun and was arrested but lawyered up and avoided serious charges. Ever the charmer, Guay somehow wormed his way back into the lives of both women, but began to plot to murder Rita.

Like I said, it was a sordid story.

Guay ran through several different scenarios to rid himself of his wife, but perhaps inspired by the story of the Philippine Airlines DC-3 in May, his twisted and remorseless mind came to focus on blowing up an airliner with his wife on board. It seems he never gave a second thought to the others who might be on that aircraft. Clearly Guay was some sort of compelling character, for he managed to acquire two accomplices in his plot to kill his wife—Marguerite Pitre who would in the final event, deliver the time bomb to the airport and Pitre's brother Généreux Ruest. Ruest, who was crippled by tubercular paralysis, worked part time for Guay as a watch repairman. He would build the bomb for Guay, for which he got or expected very little. The bomb would be delivered to the Canadian Pacific cargo office by his sister.

The day before the fatal flight, Guay purchased a round trip ticket to Baie Comeau at the Chateau Frontenac office of Canadian Pacific Airlines and, on his way out, bought a $10,000 life insurance policy on his wife from a vending machine for 50 cents. He then convinced his wife to take the flight in order to retrieve two suitcases of jewellery and watches he had cached at Baie Comeau on a previous trip. Kahn's story in The New Yorker claimed that on another occasion prior to the fatal flight, Guay and Robitaille had taken the CPAL flight to Baie Comeau, and while he looked intently out the window while timing something with his watch, she was stricken with acute air sickness. Later, it would be revealed that Guay's time calculations had the DC-3 well out over the fast moving and deep water of the St. Lawrence River when the bomb exploded. The ten-minute delay in taking off changed the outcome of the investigation and the aircraft came down on land at the edge of the water instead.

At this point it is important to state that the stories, like Kahn's, written years after the events have contained a good amount of made-up dialogue and assumptions about the people, their actions and the events. Without a transcript of the trial, it's difficult to distinguish the factual from pure creative writing. I have found dozens of articles in newspapers and magazines, some lengthy, some short, all divergent when it comes to the facts. Every once in a while, people like myself get it in their minds to tell the story, and it seems many of them have taken dubious sources at their word or were enthusiastic with their creative license. In one anthology of murder stories, Fatal Intentions: True Canadian Crime Stories, Barbara Smith writes that:

“Eyewitnesses to the crash were unanimous, they had heard an explosion and seen a box fall from the plane and plummet to the ground.

Eel fisherman Patrick Simard retrieved the box and handed it over to authorities....

... The metal box that witnesses had seen drop from the plane seconds before the crash underwent a thorough examination in police laboratories. The box contained remnants of a sophisticated and powerful time bomb. Investigators advised Canadian Pacific Airlines that their DC-3 had been carrying a massively destructive weapon.”

I found one contemporary report in the Montreal Gazette on the 13th of September that a metal box had fallen into the woods and been retrieved by Simard; but then the following day in the same paper was a report that this metal box had been found by another witness—a rail worker named Victor Duclos. Simard himself is never quoted in the papers speaking of the box. Given that many contemporary newspaper articles as well as all these subsequent magazine articles and book chapters contain wishful details and unwittingly propagated untruths, made-up dialogue and suspect material gleaned from other suspect stories, I think it's best not to get too deep into the weeds on the details of the love triangle that brought down Flight 108.

To clear up the specific matter of the metal box, I read a 1955 article published The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by the two lead forensic investigators, Franchere Pepin and Bernard Peclet, entitled The Scientific Aspect of the Guay Case. The larger article makes no mention of a box being studied or of a box at all. According to the investigators,

“A small piece of metal, painted blue on both sides, found in a parka hanging from a tree, and a piece of duraluminium, from the left baggage compartment, gave us the clue to solve this very important question. The metal from the left baggage compartment showed a voluminous white, yellow, and black deposit. It was evident that a hard object had been thrown with force against this wall. The chemical and spectrographic analyses revealed that the deposit contained zinc, carbon, manganese, lead, tin, chloride, ammonium, sodium, copper, calcium, nitrates, and many other elements. It was thus easy to state that the identifying components of a dry cell battery were present in that deposit.”

As the investigation had revealed that no such dry cell battery was known to be on board, at the take off, and that a suspect, J. A. Guay, whose wife was on board the plane, had bought some, it was thus possible to deduct that the No. 10 Eveready dry cell battery, part of which had been found, had some connection with the explosion.

Despite our analyses, a link was missing. This link was found during a search at the house and workshop of Genereux [sic] Ruest, a friend of Guay and a skilled watchmaker. It consisted in a small piece of corrugated cardboard with multiple perforations and a blackish deposit. The microscopic examination and the chemical and spectrographic analyses of this cardboard showed:

1. Presence of two very fine copperish particles incrusted in the cardboard;

2. This metal was identical with the metal of a commercial electric blasting cap;

3. Presence of all the normal elements found after the explosion of an electric detonator

We were then in a position to state that the piece of corrugated cardboard had sustained the effects of the blasting of one or more electric detonators. It was reasonable to believe that a timing mechanism had been tested before using it.' Following these numerous experiments, and considering the results obtained after examining and analysing the effects produced by many types of high and low explosives, other than dynamite, we could finally state: The explosion that occurred in the left baggage compartment of aircraft CF-CUA, whose debris was found in the forest, at Sault-au-Cochon, was due to a high explosive of the dynamite type, and in our opinion, based on experience, facts and research, this explosion was caused by a mechanical device composed of a clock, of one or more electric blasting caps and of one or more No. 10 Eveready dry cell batteries.

Typically, when the story was written about long after the events, the writer would embellish or simply guess at the facts. Take for example this gem from the writer Frederick Dannay whose nom-de-plume, Ellery Queen, is perhaps the greatest crime writer of all time. This salacious-looking double-truck story Murder over Mt. Torment published in The American Weekly was designed to titillate. Dannay's purple text describing Marie-Ange, the femme fatale was enough to make me laugh out loud: “What Guay saw was a tall teen-ager with a healthy figure and a broad face topped by school girl hair, with plucked brows above a child's clear eyes, an ample if turned-up nose... and a mouth. The upper lip was thin, almost prudish, but the lower was as full to bursting as a bud straining at the sun. Perhaps it was her mouth. Whatever it was, from that moment 23 innocent souls were doomed to a tearing, fiery death and three others were to choke their lives away at the end of a rope.” Queen also writes: “... all of Flight 108, Mrs. J. Albert Guay, the other passengers, the crew,—23 people in all—and the DC-3, exploded in midair, and crashed in flaming fragments...” which of course is simply fabricated. Photo: Corpus Christi Caller-Times via newspapers.com

As mentioned earlier, it did not take investigators more than a couple of days to suspect a bomb. The forward luggage compartment was clearly the source of the explosion and its contents were known to be only luggage and express parcels loaded at L'Ancienne Lorette. It didn't take much longer for police to follow the trail left by the naïve and incompetent conspirators to the source of the tragedy—the parcel, the lady in black who delivered it, the taxi driver who could identify her, the Saint-Sauveur neighbourhood he picked her up in, the last-minute purchase of insurance, the attempted suicide of an accomplice, the threatening with a gun charge and finally the pathetic love triangle with the Lolita-esque teen-age bar girl.

On the 23th of September, two weeks after the bombing and a few days after Pitre's attempted suicide, police brought Guay in for questioning and laid a charge of murder the next day. In a particularly sad twist, the Crown Prosecutor also revealed that a few days before his arrest, the depraved Guay, who was then aware that police were on his tail, accepted a $1,000 cheque from his Knights of Columbus council to defray costs of Rita's funeral and “to console him in his bereavement”.

On September 24th, two weeks after the bombing, Joseph-Albert Guay is brought into the provincial courthouse in Québec City for questioning, escorted by police detectives. He hides his face—but soon that face would be known and reviled by everyone in Canada. Photo: cdnhistorybits.wordpress.com

Unlike trials these days, justice was swift in 1949. Guay was remanded into custody while investigators collected evidence and interviewed the guilty parties, associates, witnesses and experts. The jury was assembled and after a few postponements, Guay's trial was set to commence in the last week of February, 1950. It would be a closed trial, “open only to newsmen, law students and officials” reported The Montreal Gazette. On February 23, the trial began with 10 of the eventual 12 jurors being selected. Just for interest, the list of jurors selected that day is worth reading... if simply for the laughable style and bizarre and judgemental content of 1950s reporting:

“In order of their selection the first 10 were: Albiny Fortin, dark bespectacled industrial foreman; Donat Savard, a brisk little glove-maker; Fortunat Hamann, labour foreman; Ernest Bilodeau, farmer; Noel Auclair, trucker; Paul Pouliot, a well-dressed forestry engineer [the jury foreman—Ed]; Johnny Topping, a big farmer who speaks no English [which is strange in that he had the only English-sounding name—Ed.]; Charles Dallaire, a mild-looking mail clerk; Jean Baptiste Guimond, a dark little farmer and Joseph Mainguy, electrician. These men and the two others still to be chosen will live in closed quarters on the top floor of the stone court house until the trial ends.”

Investigators, escorted by police, enter the courthouse carrying cardboard boxes full of physical evidence as the trial begins in late February, 1950. Note the chains on the car in the background, indicating it was during a heavy winter blizzard in progress. Image : Archives National du Québec

During the trial, Pitre testified that she had no idea that the package she delivered so carefully was a bomb, though she admitted she had purchased 20 sticks of dynamite for Guay in August, and Ruest, her brother, testified on March 5 that Guay told him the device he asked him to build was meant for blasting stumps on some future property at Sept-Îles where Guay planned to build a home. He also testified that when asking acquaintances how to make such a bomb, Guay told him to tell people it was for killing fish at “Lake Saguenay”— a fictitious lake. Ruest claimed he was paid for the building of the timed detonating device—with “a ring worth $8 0r $10.”

A mug shot of the deflated sociopath and mass murderer Joseph-Albert Guay. Photo: Random-times

On March 14, 1950, following a couple of weeks of testimony by 80 technical experts, accomplices, associates and his teenage lover, the jury retired to an adjacent chamber to deliberate. Just seventeen minutes later, the door to the chamber opened and the jury filed back in. When asked by Judge Albert Sevigny what the verdict was, the jury foreman, Paul Pouliot, answered with just one word— “Coupable!” (Guilty). It was “believed to be a record, or near record in Canadian murder trial history.” The 68-year-old Sevigny wept openly and, “choking with emotion”, immediately pronounced the death sentence on “an expressionless J Albert Guay”—sentenced to hang by the neck.

To help him build the delicate time bomb, Guay asked one of his employees, a handi-capped (note crutches in photo) watch and clock repairman named Généreux Ruest to build the device. Ruest claimed he thought the bomb with its delayed timing device was for land-clearing, namely the removal of tree stumps. The jury did not buy it however and Ruest followed Guay to the gallows. Ruest's motivation for participating in the plot is not certain, but he was in financial difficulties and had himself been spurned by Guay's wife Rita at one point.

Guay's second accomplice was his long-time associate Marguerite Pitre, the sister of Généreux Ruest, the bomb-maker. Around Québec's seedy Lower Town, she was a well-known and somewhat shady character that neighbours took to calling Le Corbeau (The Raven) because she always wore black.

Albert Guay, with police constables on either side in the dock at the courthouse in Québec City, is caught in a moment that makes him appear to be ashamed and repentant. According to Gazette reporter William Stewart, “The position of the prisoner's box in an alcove on the side of the big courtroom permitted him to keep his face averted from the crowd of spectators by turning his head a bit to one side.” Truthfully, the sociopath had no remorse or feelings about what he had done other than selfish ones. Photo: Public Domain

Guay had two accomplices in the plan to blow up Flight 108—the bomb builder, Généreux Ruest and his sister, the bomb deliverer—Marguerite (Ruest) Pitre. Photo: Newspapers.com

Guay eventually turned on his accomplices, telling police they were in on it from the beginning, perhaps hoping for a brief reprieve while he testified at their trials. His original execution date of June 23, 1950 was stayed on appeal to January 12, 1951, but he would not testify at the trials of Généreux Ruest or Marguerite Pitre. Pitre had been acquitted in March at her trial for attempted suicide (a crime long since struck from the books) and released from jail. Investigators all the while were piling up evidence and affidavits against the accomplices and, on June 6, 1950, Ruest was arrested at his rooming house and held for trial on a charge of murder. On the first day of Ruest's preliminary hearing, Pitre was once again arrested, this time for intimidation of a witness (in the chamber beside the courtroom). Newspapers reported that “she sobbed and shrieked loudly as she was taken by two burly Provincial Police officers from a corridor near the courtroom and carried to the cells.” An acquaintance posted her bail and she was back testifying at her brother's hearing the next day. After two days of hearings, Ruest was remanded for trial.

Justice Meted Quickly

Ruest's trial began on November 27, and two weeks later on December 13 at the Court of King's Bench in Québec, he was sentenced by Judge Fernand Choquette to hang March 16, 1951. His jury had been even quicker than Guay's, taking just 13 minutes to find him guilty. Just two days after his sentence, Marguerite Pitre was arrested and charged with murder.

Despite pleas for a stay of execution, on January 12, 1951, a few minutes after midnight and just 16 months after he murdered 23 innocent people, Joseph-Albert Guay, 32, was escorted to the gallows at Montréal's Bordeaux Common Gaol. At 12:43 in the morning in the dead of winter, the trap fell away. Five minutes later, he was pronounced dead by the Bordeaux prison doctor. His last words apparently were “Au moins, je meurs célèbre” (At least I die famous).

A few months later, on March 6, Marguerite Pitre's trial began. On March 15, her brother Généreux Ruest, received the first of his stays of execution, just hours before his date with the hangman. Two days later, his sister's trial commenced, and like all of the trials so far, it was over in a matter of weeks. On March 19, she was sentenced to death by Judge Noel Belleau, with hanging date fixed to July 20, 1951. This time, the jury took 29 minutes to deliberate. She later appealed and was granted a stay.

Ruest, now 54, would finally meet the executioner at Bordeaux shortly after midnight on July 25, 1952. He was pushed to the gallows in a wheelchair and hanged sitting down. His sister's hanging was scheduled for the following October, but she was granted another stay. However, on January 9, 1953, Marguerite Pitre, 43, was finally escorted to the gallows at Bordeaux, no mercy granted for being a woman. The trap dropped at 12:35 in the morning. She was the eleventh woman to be hanged in Canada, and the last.

Marguerite Pitre arrives, escorted by prison officials and nuns, at the Fullum Street Women's Jail in Montréal on January 8, 1953 to await her execution the following day at the men's prison at Bordeaux. Bordeaux Prison Chaplain Roger Jeannote said in 1975 "She arrived at 5 p.m. from the women's prison. She insulted the nuns that were with her. She had been drinking. She sang a little ditty "Prendre un coup c'est agreable." (Take a shot, It's nice). I talked a little with her in her cell She talked about her two children. We said the rosary dozens of times. She finally joined in, enthusiastically. 'I never thought you'd get me.'" I was curious about the “ditty” that an inebriated Pitre was singing as she was led to the gallows. I found a YouTube video/recording of La Famille Soucy (Soucy Family) singing this fun little drinking song and further research indicated that the song originated in France and was found in the folklore of both Québec and Louisana. Photo via Newspapers.com

Epilogue

These days, thanks to terrorism, it's pretty difficult to bring down an aircraft using a time-bomb placed in a piece of luggage or in a package in the cargo compartment. Exceedingly difficult, but not impossible. Technology provides us layer upon layer of screening that keeps us safer, but less free. And any technology can be broken. To bring down an aircraft for political purposes is no less heinous than bringing one down for the pathetic and weak reasons that the fool Guay had. Each and every aircraft bombing is an act of utter callousness and selfishness which claims the lives of innocents and never works to achieve the desired goal, unless of course, the goal is simply to terrify.

Today, the wreckage of CF-CUA still litters the forest floor above Sault-au-Cochon — some of it taken by souvenir hunters, all of it disturbed somewhat in the 70 years since the tragedy. To see more images by Jean Pierre Filion of the crash site and surrounding area, visit jpfl/mywhc.ca Photo: Jean Pierre Filion at jpfil/mywhc.ca

The elegant post-war livery of Canadian Pacific Airlines can still be seen clearly on torn bits of fuselage skin. To see more images by Jean Pierre Filion of the crash site and surrounding area, visit jpfl/mywhc.ca Photo: Jean Pierre Filion at jpfil/mywhc.ca

Post Script

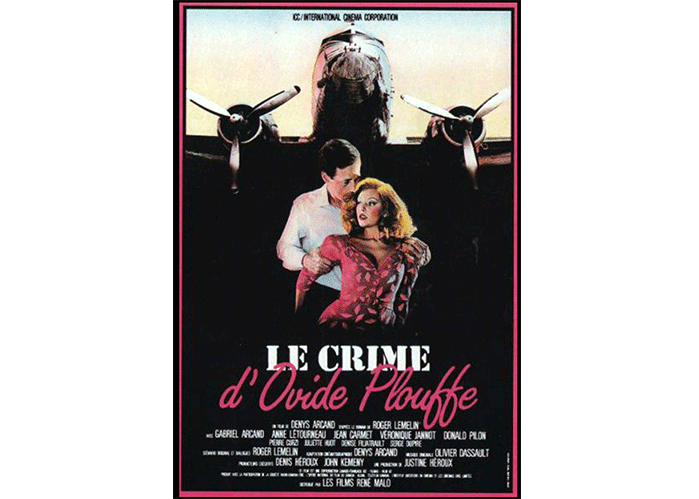

Guay's unthinkable crime of passion inspired Québec's most famous fiction author, Roger Lemelin (and an acquaintance of Guay's) to write the novel Le Crime d'Ovide Plouffe based on the true facts but with a fictional group of characters, which was turned into a feature film. Instead of Guay, an obsessed man named Ovide Plouffe was the mastermind. The name Plouffe may have been inspired by the fake Baie Comeau addressee of the package that contained Guay's bomb—Alfred Plouffe. The film was directed by Denys Arcand, Québec's most famous film director, known for his critically acclaimed, sexually charged and thought provoking films like The Barbarian Invasions (Academy Award), Jesus of Montreal (Academy Award nominated) and The Decline of the American Empire (Academy Award nominated).